THE NAPIER COMMISSION IN ORKNEY

Part 4 of 4

Statement of

Lieut.-General F. W. Traill Burroughs, C.B., of Rousay, Orkney.

I think it right in supplement of the evidence given before your Lordship’s Commission in Kirkwall on the 23rd July 1883, to send you the accompanying copy, furnished to me by the procurator-fiscal of this county, of an anonymous threatening letter received by me on the 1st of this present month, the day on which, by the postmark, it was posted in Rousay. I have placed the letter in the hands of the authorities, and they have traced it to Sourin, the district whence came the Free Church minister and the disaffected who appeared from Rousay before you. The authorities are still engaged in tracing its author. The letter will show your Lordship and your fellow Commissioners the style of the witnesses who appeared before you, and of their friends; and that they are endeavouring to establish a reign of lawlessness and terror here, as in Ireland. May I request that this anonymous letter, of which I enclose a copy, may be printed along with the evidence in the case as affecting Rousay. Several anonymous communications have reached me since the meeting of the Commission in Kirkwall but the enclosed is the worst.

F. BURROUGHS.

TRUMBLAND HOUSE,

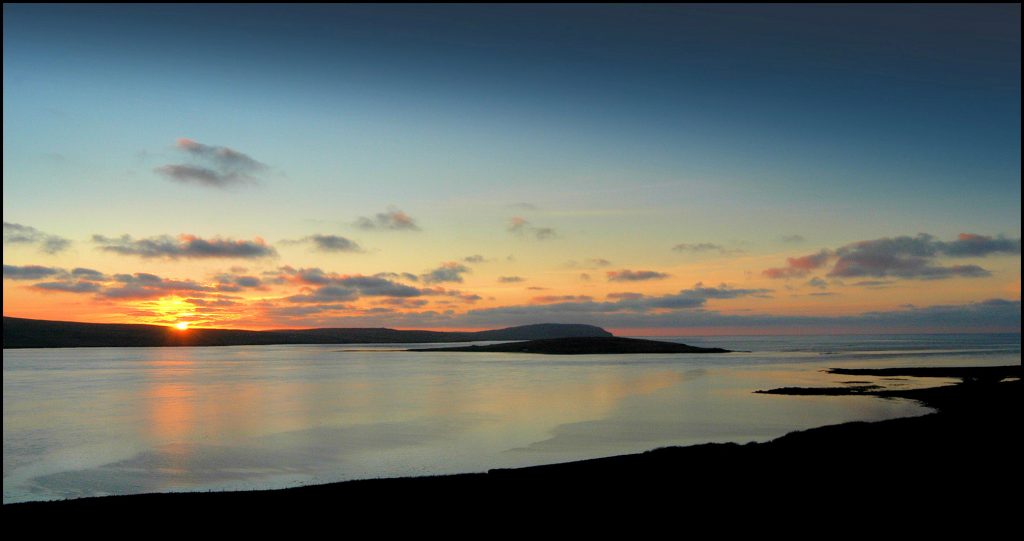

ROUSAY, ORKNEY, N.B.

22nd August 1883

Copy of a Threatening Letter sent to General Burroughs

GENERAL BOROUGHS,—Sir, I havee Noticed in the Papers that you are determined to Remove these Men that give Evidance to the Comission in Kirkwall, well if you do, as sure as there is a God in Heaven if you remove one of them there shall be Blood Shed for if I meet you Night or day or any where that I get a Ball to Bare on you Curs your Blody head if it dose Not Stand its chance, thire is More than we intended nail you. you are only a divel and it is him you will go and the sooner the Bitter, and if you should leave the Island if it should be years to the time you shall have it. O Curs your Bloody head, if you dont you devel the curse of the poor and the amighty be on you and if he dos not take you away you shall go So you can persist or not if you chuse but be sure of this you shall go. I state No time but the first Conveniance after there removal.

Envelope addressed thus :-

General Borougs C.B

Trumbland House

Rousay

Post mark on the envelope :- Rousay ‘Aug. 1, 83’

Alleged Evictions of Crofters of Rousay, Orkney.

I. – Statement by James Leonard, Crofter, Digro, Rousay.

Queen Street, Kirkwall.

28th November 1883.

General Burroughs having published a statement, dated 13th October last, on the subject of the crofters’ complaints, it is deemed of importance that his statement should be corrected (as The Scotsman newspaper of Edinburgh, through whose columns the statements appeared, refuses to insert any correction of the same), that full evidence may be before the Royal Commission. We were the more desirous of this, as the time at the disposal of the Commission in Kirkwall did not admit of the delegates stating all they considered should be known.

1. General Burroughs stated that the delegates were (some of them) not tenants of his, and that they did not represent the body of the tenants. On the contrary, all of the delegates were tenants under him, and had paid rent regularly, and that they did represent the whole body of the tenants almost without exception was shown, and is proved beyond doubt by the following facts. Shortly after the meeting of the Commission in Kirkwall an attempt was made in Rousay to weaken the testimony the delegates gave at that time. The form which that attempt took was that of a ‘memorial’ to the proprietor, Lieutenant-General Burroughs, in which it was stated that the statements of the delegates were not accurate, and had not been properly authorised by the tenants. It will be remembered that one of the complaints made by the Rousay crofters was that there was an amount of ‘landlord terrorism’ felt by the people that was unendurable. In view of this fact (which might have been kept in view by the promoters of an address or memorial got up to disparage this and similar statements), care should have been exercised to avoid the very appearance of the slightest exercise of the influence of proprietor or factor in connection with this memorial, especially in asking the people to sign it. The occasion, therefore, on which the proposed memorial was first brought to the light of day was, in view of these considerations, very unhappily chosen. It is an annual custom of the proprietor to have the school children of the island and their parents to Trumbland House (his residence) at the close of the school year to enjoy a picnic at Trumbland. In the course of this day, on which many of the tenants were present as invited guests, the memorial referred to was produced, and tenants were asked in Trumbland House to sign. Only one or two did sign – a fact which speaks for itself, and full of significance to all who know the courteous and obliging nature of Orkney people. Further efforts were made, however. The memorial was carried round the district of Wasbister by one who gave a whole day’s hard work, in which he visited every house (with two exceptions, we believe) in the district, but by which, after all this disinterested and zealous labour, worthy of a better cause, he only obtained two signatures. The other district of Frotoft was still more barren, and only produced one. After this it was judged needless to visit the other district, Sourin – in fact, nobody could be got there to take the thing round for signatures. This ‘very numerously-signed memorial’ has never been given to the public, nor seen the light.

2. As to the evictions from Quandale and Westside, General Burroughs said that it had been for the benefit of the estate, because they formerly brought him only £80, but are now rented at £600. This is an entire mistake. It is the farm of Westness – to which Quandale and Westside were added – which brings in the rent of £600, and, before Quandale and Westside were added to it, it was the most valuable farm in the island.

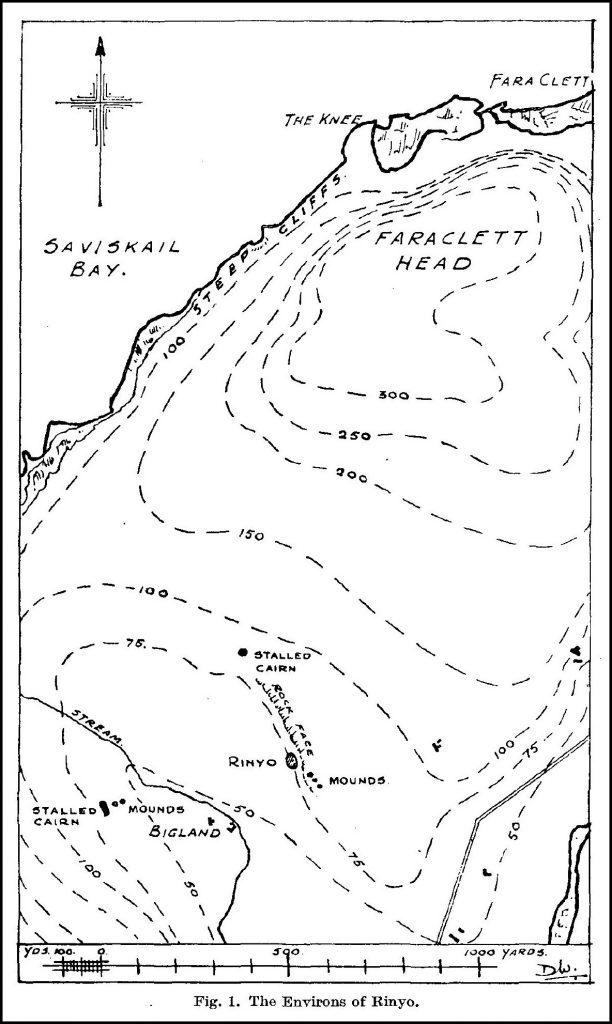

3. When asked by Lord Napier if he, General Burroughs, had ever evicted any without giving them another place on his estate, he replied that he did not remember any; but he might have remembered the following cases of recent date, viz., Edward Louttit of Westside; James Sabiston, Veira; Thomas Sinclair, Hurtiso; and Widow Gibson, Langskaill, – none of whom got any footing on the Rousay estate. Hugh Inkster, Hammer, and William Louttit, Faraclett, have also been evicted from their holdings, although allowed to remain in cots. These and others are in addition to the evictions formerly mentioned in Quandale and Westside, Nears, &c.

4. It is right to inform the Commissioners of the arrangement of the road and poor rates on the Rousay estate. General Burroughs stated before the Royal Commission that he ‘always supported the poor himself,’ but he did not state the local arrangement how he does this, viz., that the tenants pay all the road monies. How does this arrangement work? General Burroughs stated, in reply to one of the Royal Commissioners, that about £100 a year was spent by him on the poor. Now the tenants pay a shilling in the pound of rental, and this gives the annual sum of about £160. General Burroughs himself said, in reply to another of the Royal Commissioners, that the rental of his estate is £3256. Now, a shilling out of the pound of a rental amounting to £3256 yields about £160 a year of road rates paid by the tenants, as against £100 a year of poor rates paid by General Burroughs, the landlord. This is, indeed, a very fine arrangement for General Burroughs. He gets £60 more on the road rates than he spends on the poor. Is this just to the tenants? And how does he support the poor? He takes a very high road rate from his tenants, a shilling in the pound of rent – and he gives the poor a sheer starvation-rate of support. Details will prove this. He gives some of his pauper poor 16s. a year, others 32s., others £2, – and the highest, as was stated by the inspector of poor, is £4 a year. Well might one of the Royal Commissioners ask, ‘Is it possible for people to live on that?’ The fact is, the Rousay poor, whom the proprietor supports, would simply starve if their neighbours and friends did not take pity on them and support them. The tenants submit to this kind of treatment because they cannot see their fellow creatures die, and because they well know complaint to the estate management is useless and worse than useless, for while it would get no good to the poor, it would only bring down on whoever dared to breathe a complaint wrath, and more rack-renting, and, in good time, eviction – as witness what has now occurred, the eviction of two of the crofters’ delegates.

5. A special instance of the way in which the support of General Burroughs’ poor is managed was that of George Flaws, a poor, afflicted, but very deserving man at Frotoft in Rousay, in the spring of this very year requiring parochial relief. Did the proprietor provide it for him? What was done was this – the factor got men to go round and collect subscriptions from each house in the several districts for this poor man; the tenants, who pay double road money on the understanding that the proprietor will support the poor, thus supporting this poor man also. We would like to hear General Burroughs on this question of the poor and the roads. But we may say it has recently been decided, after several years’ investigation by the Orkney Road Trustees with reference to this Rousay road question, that it is illegal for tenants to pay both their own and the proprietor’s part of the road rates; yet this was done for years past here.

6. The painful duty has now to be discharged of reporting to you that since your sitting as a Royal Commission in Kirkwall, two of the crofters’ delegates have been evicted by General Burroughs, viz., James Leonard and James Grieve. General Burroughs obtained in the Sheriff Court at Kirkwall decrees for their ejectment from their houses and homes, and these decrees order that they shall not merely be removed from their present holdings, but that they shall not be received into any other house or cottage on the Burroughs’ estate. They are so evicted simply and avowedly because they appeared and acted as delegates They are both natives of Rousay, and related by blood or marriage to a large number of the people of Rousay. Neither of them were at all behind with their rent. A further hardship and wrong in their case is that both of them are evicted from houses which they built themselves at their own cost. First, James Leonard was the crofter of Digro. About sixty years ago his father reclaimed the lands of Digro croft from the ancient commons, or hill pasture, of Rousay and sat for many years there without paying rent to any man. For twenty years back James Leonard has been the crofter of Digro, under General Burroughs and improved the land during that time. Ten years ago he built a new house upon the croft at his own cost. From all this he is now evicted without compensation for any of his improvements or for the new house; but General Burroughs paid him a small sum for the fixture woodwork of his house, thereby acknowledging him, at any rate, as the tenant, which he had formerly denied. Second, James Grieve built a cot in addition to the steading of Outerdykes croft, which was his father’s before him, and from this, without compensation, he is now evicted. We protest against these evictions of men who simply did their duty as delegates of their fellow-tenants at the call of Her Majesty’s Government and Commission appointed for the very purpose of hearing evidence. I request in my own name, and that of my fellow-delegate, James Grieve, that you will report these evictions to Her Majesty’s Government, that they may, by Act of Parliament or otherwise, provide compensation for our loss and disturbance, and render such evictions, and especially the taking away of improvements without compensation, illegal. It is obvious that our eviction is wanton and unrighteous, and we claim that the commons be restored to the people and ourselves to our houses. We trust you will report these matters to the Government for redress without delay.

7. In his published statement General Burroughs professes to have been surprised at the evidence given before the Commission, and tries to create an impression that the Church and the influence of ministers in Rousay raised the crofters’ movement, especially that of the Rev. Archibald MacCallum of Rousay Free Church, who acted as one of the delegates and read their statement. This is an utter error, and is like the similar charge made by a factor against the Roman Catholic clergy in one of the islands of the Hebrides, which their bishop, Dr MacDonald of Argyle and the Isles, publicly declared was unfounded. We cannot understand General Burroughs’ surprise. He had only too many complaints and disturbances long before the Commission. Such were the disturbances, as was stated in the evidence, that both he and his factor went together and repeatedly visited tenants to secure quiet, and his law agent, the procurator-fiscal, Mr Macrae of Kirkwall, did the same, but with little success. General Burroughs then wrote to the Rev. Mr MacCallum to visit his tenants. It was by this act of General Burroughs himself that Mr MacCallum was first asked to intervene. And General Burroughs, by stating in his letter that, if quiet did not ensue, the subtenants would have to be removed, intimated that it was the arrangement of the land that was the cause of dissatisfaction and disturbance. Mr MacCallum replied that it was idle to expect peace here or elsewhere unless that justice, of which peace was only the fruit, was observed. It passes comprehension, then, how General Burroughs could pretend that all around him was in ‘peace, happiness, goodwill, and contentment’ until shortly before the arrival of the Crofters’ Commission. Mr MacCallum was south the whole time the agitation lasted in Rousay, away from the island altogether, till about ten days before the meeting of the Commission in Kirkwall. Immediately on his arrival home a deputation of the crofters visited him and asked him to help them in stating their evidence. He did not consent to do so on the first visit of the deputation, but only heard their wishes and promised to consider their request. On a second visit of the deputation he agreed to attend our last meeting, and read our statement.

8. Lord Napier asked – Is it a matter of discontent or suspicion in the place that the procurator-fiscal stands in the relation of a factor to the proprietor, or did he ever act as factor? I beg to inform the Commission that he did so act and that some time ago, when complaints were strong and numerous about high rents, General Burroughs spoke to him on the subject, when he (Mr Macrae) came out from Kirkwall and went over the island with the proprietor, and valued, or professed to value and even analyse the land. I do not know where he learned how to analyse or even value land, but certainly his way of valuing and the results were most extraordinary. He went about the island carrying a small garden spade, with which he dug up a few inches of soil here and there. I may mention the fate of this spade. It was as follows – He was digging a spadeful of the tough soil of Triblo croft, when the tenant warned him to be careful or else he would break his spade. But he replied, ‘No fear of that, I know what it can bear’ when immediately the spade broke. On another farm he said to the tenant that it was magnificent soil but for the amount of salt (whether too much or too little is not remembered) in it. The tenant answered, ‘that’s very strange, Mr Macrae, as a large practical farmer, who was here a short time ago, said the very opposite.’ How he professed to ascertain the amount of salt is not known, but sometimes he would dig up a handful of soil with his toy spade, then rub it in his hand, and afterwards taste it by chewing it in his mouth. In another place, he said no man could teach him how to value land, and that this land, if it was in the Carse of Gowrie, would be rented at £4 an acre. On the farm of Essaquoy, in Rousay, he came across a field which consisted of a bed of solid rock, covered with a thin layer of earth too shallow for the plough. He said to the proprietor, If this man (pointing to the tenant) had a little capital, he could, by blasting the hold, make splendid land of it and that he had seen this done in other places. The farmer replied, there was a little earth on it at present, but he was afraid that after the blasting there would be none at all. It is unnecessary to add that this way of valuing did not end in any relief to the tenants, although General Burroughs said at the meeting of the Commission in Kirkwall that ‘he always found the leanings of lawyers and factors were towards the tenants.’ I would respectfully beg the Commission to advise the Government that the office of procurator-fiscal should not be allowed to be held by any person who acts as agent, land valuator, or factor for any proprietor in the same county.

9. The Commission may be aware that shortly after the Kirkwall meeting General Burroughs received a post-card, and a letter said to be of a threatening character. From a second post-card, addressed to the editor of the ‘Orcadian’ newspaper, of 24th August last, professing to be from the author of the post-card addressed to General Burroughs, it would appear that no threats whatever were used in it, although strong opinions were expressed about the way General Burroughs had acted before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall. A threatening letter, however, is an odious thing, and I cannot believe that any one of the crofters ever wrote such a letter. The letter in question is supposed to be in the handwriting of a boy. At any rate General Burroughs acted as if he thought so. He inquired at the schoolmasters of Rousay if they knew the handwriting. It is a question whether it was competent for him, a magistrate, to act in his own case in this way.

After this the island was visited by a most imposing array of officials of the Crown. Sheriff-Principal Thoms, Sheriff-Substitute Mellis, Procurator-Fiscal Macrae, Mr Grant, county superintendent of police, and Mr Spence, clerk of the fiscal, sailed from Kirkwall in one of Her Majesty’s gunboats and landed in Rousay, in order to examine two boys. There was no evidence whatever against either of these boys except the handwriting of the letter was said to be like the handwriting of one of them. One of the boys was my own son, Frederick Leonard, aged fourteen, the other was the son of a neighbour who had taken a leading part in the crofters’ meeting – his age was fifteen. On landing at Rousay, Sheriff Thoms visited General Burroughs and remained in his company throughout the day. This indeed was nothing unusual, as the Sheriff always, when in Orkney, paid friendly visits to the general.

The fiscal, Mr Grant, and Mr Spence then came along to the schoolhouse, Sourin, Rousay. Mr Grant and Mr Spence went to the neighbouring farm of Essaquoy, where my boy Fred was herding cattle. They did not ask for me, or for his master. They did not show any warrant or summons. Without any previous notice or warning of any kind, and without stating any charge, they demanded that he should come along with them to the public school, where they said someone wanted him. The poor boy, entirely ignorant of their business, and no doubt alarmed, had to comply. On arriving at the school the scholars were dismissed, and after a good deal of shuffling and wondering what poor Fred was doing there, a clearance was effected. The tribunal sat, and Fred, without any friend to speak a word of comfort to him (for none of us knew anything about it more than if he had been stolen), was called to face them alone – enough to have deranged a nervous tempered boy. All things ready, pen and paper were handed to him, and he was made to write to dictation, which he did according to the best of his ability for a considerable time, until, as he expressed it, he was tired. The boy was made to write such expressions as ‘Curse your bloody brains.’ After this he was sent out of the school, and kept there in the custody of Superintendent Grant; was again called and shortly afterwards dismissed.

The reason of all this is still a mystery to me. The question very naturally suggests itself – Why was the poor herd-boy, who was apparently concerning himself as much about these things as the cattle he was tending, singled out? Was there anything peculiarly bad about him that he should be suspected? No; he bears a character as untarnished by vice as the general, or his friends the sheriff or the fiscal. Why then was he arrested? I cannot tell. It could be nothing against him in the eye of the law, that he was the son of one who acted as a delegate of the crofters.

The other crofter’s son, Samuel Mainland by name, was apprehended in the neighbouring island of Stronsay, on the following day, by Superintendant Grant. No warrant or summons was shown. They sailed from Stronsay for Kirkwall about one o’clock, and arrived at Kirkwall a little before twelve the same night – not having been offered food for ten hours. Nor did he receive any in the lodgings to which Superintendent Grant took him till the following morning, thus being twenty hours without food. At ten o’clock in the morning he was brought before Sheriff Thorns and Fiscal Macrae in the Court-House, Kirkwall, and was privately examined by them at great length, till close upon one o’clock in the day – nearly three hours. He was examined partly about the letter referred to, but principally about the meetings held by the crofters in Rousay – who was at them, and what was done at them – of which the poor boy knew little or nothing. He was asked, for example, what I had said at the meetings, and especially what I had said when the delegates landed on the shore of Rousay the night they returned from the Commission at Kirkwall. After this three hours’ examination was over, the boy was set at liberty, shown out of the Court-House, and left to find his own way home from Kirkwall to Rousay. It has been said to me by his father that the boy was not himself again for some time after undergoing this singular trial.

The following week Mr Macrae made another visit to Rousay, as fiscal, about this letter in which General Burroughs was threatened. The party then visited was also connected with the crofters’ movement, having attended the Commission at Kirkwall as one of their delegates, and read their statement. This next visit was to the Rev. Mr MacCallum, whom Mr Macrae visited at his manse, accompanied by Superintendant Grant and Mr Spence the fiscal clerk. This visit was the last they paid on this matter. Mr MacCallum threatened to report the whole proceedings to the Lord Advocate. He inquired on what ground Mr Macrae had thought proper to visit him in connection with such a matter. Mr Macrae, in reply, said he had been informed that Mr MacCallum had said that no native of Rousay had written the threatening letter, and that he had said so to the wife of a servant of General Burroughs. Mr MacCallum asked the fiscal, ‘ Did the woman pretend to think that he had any knowledge of who had written the letter, or that he had said anything that could mean that.’ Mr Macrae stated that he had visited the woman, and that she had declared that she had not any such thought at all about it. Mr MacCallum stated that in that case it was surely a very uncalled for proceeding to visit him in connection with that matter. These things are now stated for the information of the Commission, who may imagine the effect they were calculated to have upon a people unaccustomed to the law and its terrors.

I have to express my regret that is necessary to trouble the Royal Commission with this supplementary statement, but I submit it to you with the deepest respect, and out of a desire to do my duty, and give full evidence as a delegate to you, although I and my brother-delegate have suffered eviction from our houses and homes for simply giving evidence, according to our convictions before you. I request you will give full consideration to our case and our complaints, which are already before you. I beg respectfully to request that you will insert our supplementary statement in your report of evidence to Parliament, in addition to our former statement and evidence.

JAMES LEONARD.

II. – Statement by Lieut.-General F. W. Traill Burroughs, C.B., of Rousay.

1 Athole Crescent, Edinburgh.

11th January 1884. Rousay.

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of a copy of a document purporting to be a ‘supplementary statement on behalf of the tenants and crofters’ of Rousay, and submitted to the Royal Commission (Highlands and Islands) by James Leonard, who styles himself – ‘Crofter, Digro, Rousay, and chairman and clerk of the crofters’ meetings,’ dated Kirkwall, 28th November 1883.

As requested in the letter forwarding to me the above document, I now send to the Commission a copy of a letter I wrote to the newspapers on the 13th October 1883 :—

To the Editors of “The Scotsman” and “Orkney Herald”

THE ROUSAY EVICTIONS.

Trumbland, Rousay, 13th Oct. 1883.

1. SIR, – I observe in your paper of the 10th inst. a paragraph headed “Eviction of Rousay Crofters,” which proceeds to say that James Leonard and James Grieve have been warned out of their holdings.

2. Neither James Leonard nor James Grieve are Rousay crofters.

3. James Leonard’s father did up to his death, some months ago, hold from me a small farm named Digro, of about nine acres in extent, in the district of Sourin, Rousay. His son James, who is precentor of the Free Church here, never was my tenant, but he is anxious to be so; but after having poured out a string of complaints in very uncomplimentary language against me, as reported in detail in some four columns of a local newspaper, in which he and the Free Church minister in this parish combine in describing me as un-Christian, inhuman, unrighteous, unjust, oppressive, &c, &c, James Leonard says, “he was always opposed to General Burroughs,” and would oppose me till death; that they had a local despotism which they wished removed; that “in every battle some had to fall; though he should fall in this battle he would fight it out.” and “a man’s a man for a’ that!” and other similar sentiments. As no business, whether of agriculture or of any other description, can prosper where such want of unanimity exists between those engaged in it, I decline to accept him as a tenant. And I do not think any other employer would employ anyone who threatened to be so troublesome. He is by trade a mason and a weaver, and he is a teacher of singing, and is not dependent upon farming for a livelihood.

4. James Grieve, too, is not my tenant. He returned a few years ago from the colonies, boasting of having made money, and that he was looking out for a farm. He came to visit his brother, who is tenant of Outerdykes in the district of Sourin, Rousay. He married a housemaid who had been some years in my house, and out of kindness to her, her husband was permitted to squat for a time on his brother’s farm to enable him to look out for a farm for himself. Years have passed, farms in various parts of this county have been advertised to be let, but James Grieve is still here. He joined the Free Church minister in his attack upon me, and said he agreed in his evil opinion of me; that my tenants were “in a condition generally of great and increasing poverty;” that they were ground down and oppressed, and generally most miserable. I have no wish that any of my tenants should be miserable, and not being desirous of being a party to James Grieve’s misery, I decline to accept him as a tenant.

5. I may add that when my wife and I left Rousay last winter, we left home and all round us in peace, happiness, goodwill, and contentment. We were on friendly terms with the Free Church minister, and had been so with his predecessor the Rev. N. P. Rose, who visited Rousay shortly before the arrival of the Crofter Commission. The only differences I ever had with the Free Church minister were differences of opinion on School Board matters.

6. From James Leonard’s father I never had a complaint during the thirty years I knew him. He was a very respectable peaceable man, and I had always been on the most friendly terms with him; From his son James too I never had a complaint, excepting in my position of chairman of the School Board, when he complained of inhumanity (a favourite expression of his) against a teacher. James Leonard called on me on the 29th September, and asked me whether I was in earnest in intending him not to have the farm of Digro? I said I was, and explained to him why. He said he had no ill-will against me; that he had been put up to it to appear against me, but that he did not mean it, and that he had been told that funds would not be wanting to oppose me.

7. From James Grieve, too, I never before had a complaint, excepting that he objected to pay for fuel, and that he wanted a farm, and there was no farm vacant to suit him.

8. My surprise, therefore, may be imagined at the torrent of invective that was so freely poured out upon me by the Free Church minister and his delegates before the Crofter Commission. On leaving home in my steam yacht on the morning of its sitting in Kirkwall, I passed the Free Church minister and his friends becalmed in a boat about a mile from Rousay. Seeing their difficulty, and that they might be too late for the meeting, I towed their boat some eight or nine miles into Kirkwall, which, had I suspected their spiteful attack upon me, I need hardly say I should not have done.

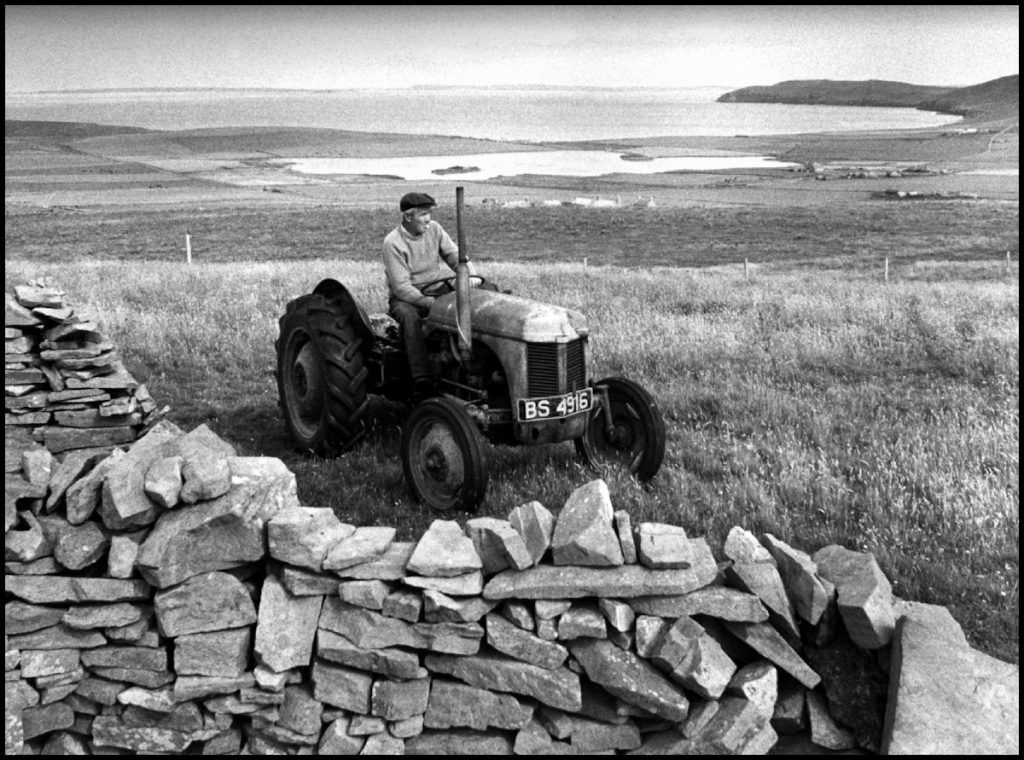

9. Since I succeeded to this estate it has ever been my endeavour to do my duty by it, and to advance the wellbeing and prosperity of all on it. The measure of success that has attended my efforts is apparent to all who remember Rousay then and see it now. To those unacquainted with the locality, I may mention that when I first came to Orkney in 1848 there were no roads in Rousay, and consequently very few carts. Now there are some twenty miles of excellent roads, and every farmer has one or more carts, and many have gigs and other description of carriages.

10. Then there was no regular post to the island, and no regular means of communication from the island to anywhere beyond it, or even to any place within it. Now there is a daily post to and from the island, and a daily post runner around it.

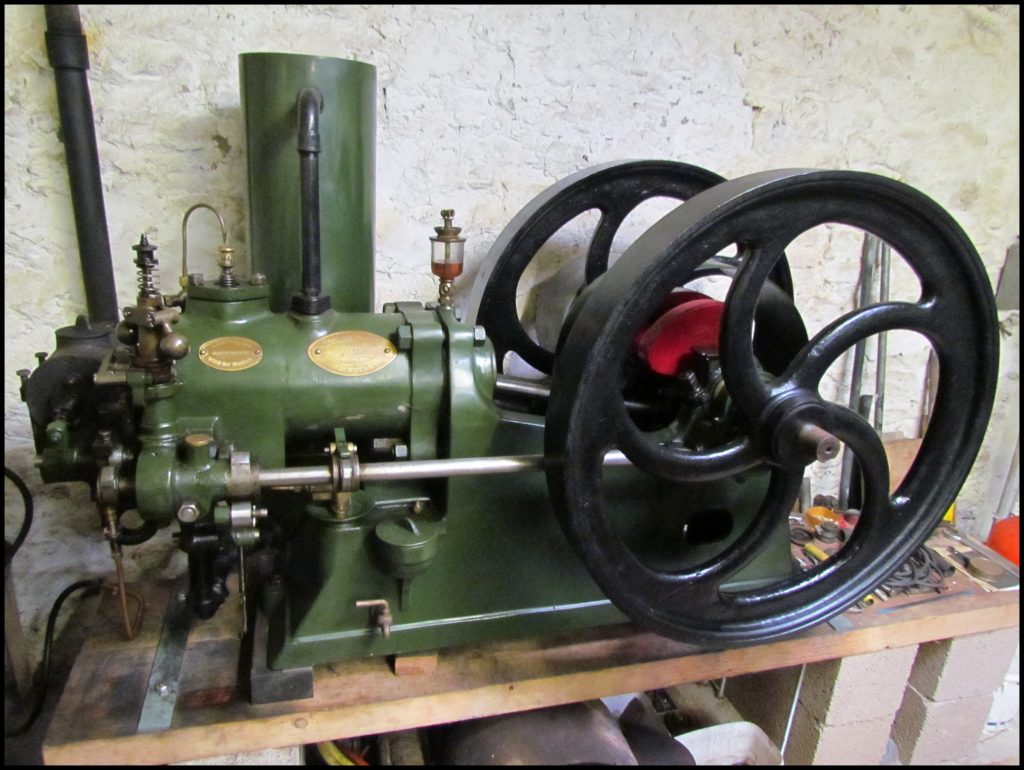

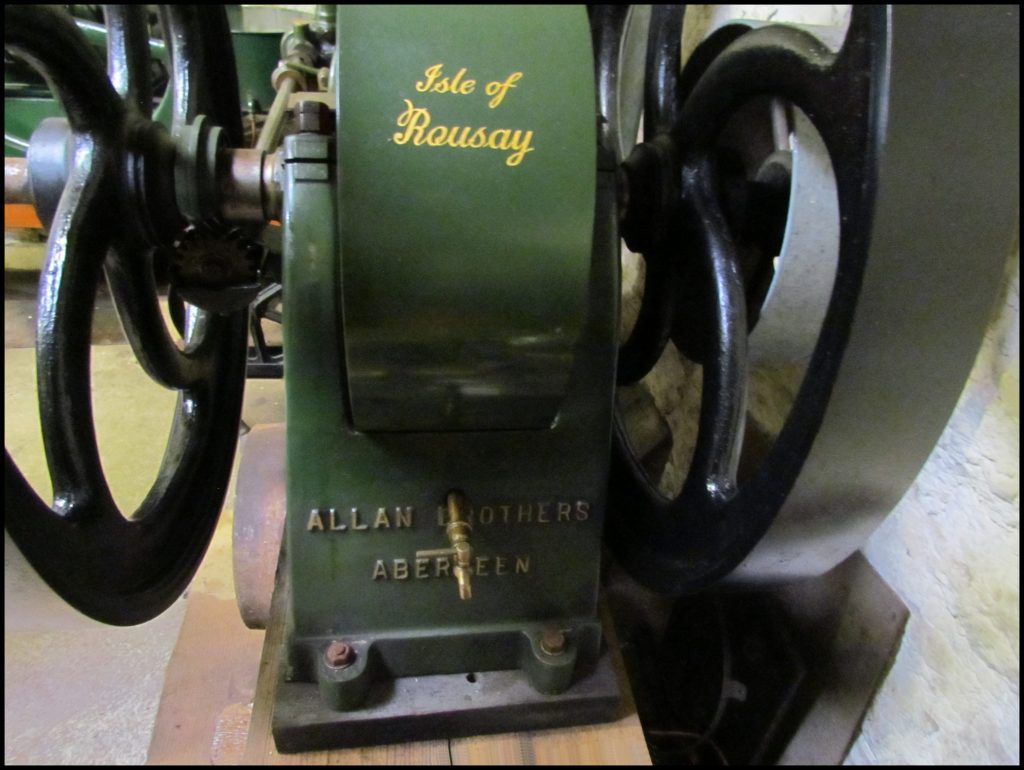

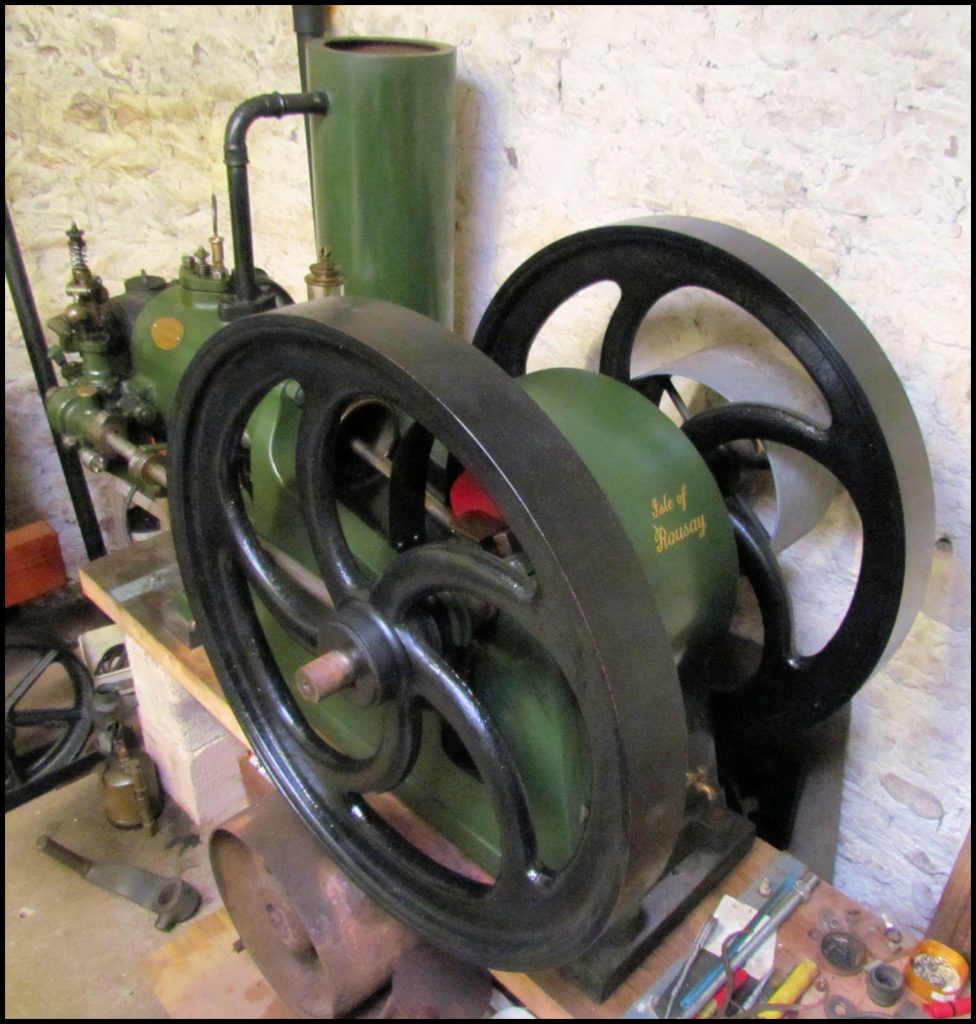

11. There was then no pier, and no public means of transit of goods to and from the county town. Now there is a pier, built at my own expense, and a steamer, of which I am the principal shareholder, plying regularly to and from Kirkwall, but which has not yet paid a dividend!

12. Then the houses generally were very comfortless, few had any place beyond a stone in the centre of the dwelling, with a hole in the roof above it. Now such an arrangement is hardly to be met with. Many new houses and steadings have been built by me at considerable expense, and to encourage comfort, prizes are annually awarded to the cleanest, prettiest, and best kept cottages.

13. Agriculture was then in a very primitive condition. Now as good crops of oats, bere, and turnips are to be seen here as anywhere in the kingdom; and the sheep and cattle will now bear favourable comparison with those of most counties.

14. We have, too, our local Agricultural Society, with annual ploughing and hoeing matches, and a cattle show. And we have our battery of volunteer artillery.

15. In fact, the Rousay of to-day is a very different place to what it was thirty-five years ago, and how anybody can truthfully say that the condition of its inhabitants is one of “great and increasing poverty,” as stated by the Rev. A. MacCallum, passes my comprehension.

16. Since I retired from the active list of the army, my wife and I have made Rousay our home. We have built a new house, and laid out its grounds, and have given much employment to those around us, and she has been the prime mover in all affecting the happiness and welfare of the inhabitants of the island, many of whom have written to us, and most of those whom we have met since the visit of the Crofter Commission have voluntarily told us that they did not share in the movements or sentiments of my detractors. And I have received most kind and thoughtful letters of sympathy from hundreds of old soldiers of my old regiment – the 93rd Highlanders – from all parts of Scotland, telling me “that they are full of indignation and anger at the treatment you have received, for they cannot think that he whom they served so long, and who treated them on all occasions with so much kindness and liberality, could behave so differently to others.”

17. My surprise, therefore, may be imagined at the torrent of invective poured out upon me by the Free Church minister and his friends.

18. And my surprise was still greater at receiving an anonymous threatening letter, a few days after the meeting of the Crofter Commission in Kirkwall threatening me with death should I ever remove a tenant from my estate. I have often been shot at before, and am not to be deterred from doing what I consider right by such a menace, which I can but regard as a new formula of the highwayman’s threat of old, now rendered as – “Your land, or your life !”

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

F. BURROUGHS.

This letter answers, I think, all the charges now repeated against me in this document, and which I thought I had already answered in my evidence before the Commissioners at their meeting in Kirkwall on the 23rd July 1883. It also answers the series of attacks which have appeared against me, now under the signature of ‘James Leonard,’ and now under that of ‘James Grieve,’ almost weekly in the correspondence columns of the Orkney Herald newspaper, since the sitting of the Royal Commission in Kirkwall. I will therefore merely supplement in this letter whatever may not be sufficiently explained in my letter of the 13th October.

Before doing so I would wish to draw the attention of the Commissioners to the style and diction of this so-called ‘supplementary statement.’ It is not that of an uneducated labouring man in James Leonard’s position, although signed by him, but is evidently the work of the same person who drew up the ‘statement’ read before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall on the 23rd July I883. Some explanation of this may be gleaned from the remarks made to me by James Leonard on the 29th September 1883, as noted in the concluding sentence of paragraph 6 of my letter of the 13th October, when James Leonard told me, in the hearing of a witness: He had no ill-will against me; that he had been put up to it to appear against me, but that he did not mean it, and that he had been told that funds would not be wanting to oppose me. The conversation I had with him on that occasion was so remarkable, that after he left me I wrote it down and sent it to the procurator-fiscal of the county, as throwing some light on the secret springs of the agitation, which certain outside agitators were endeavouring to raise in Orkney.

I may also mention that in Orkney, where the true circumstances of the case are known, little sympathy has been expressed for the so-called ‘evicted.’ But endeavours are being made, by publishing distorted and untruthful statements regarding them, to extort money under false pretences from a sympathetic but too credulous public at a distance from and unacquainted with the true state of the case.

As I stated before the Royal Commission, and as I have repeated in my letter of the 13th October, I now reiterate that, from the many assurances to the contrary which both my wife and I have received since the sitting of the Royal Commission in Kirkwall from almost all our tenants, I am sure that the Rev. A. MacCallum and his delegates represent but a very small minority of them. I have fully explained in my letter of the 13th October what I stated before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall, and which I now repeat, that neither James Leonard (Digro) nor James Grieve ever were my tenants. Both their fathers were, but they never were; nor is either of them his father’s eldest son to give him any claim to succeed to any portion of an unexpired lease. The croft of Digro – some eight acres in extent, and abutting on the public road of Rousay – up to the death, in the winter of 1882-83, of Peter Leonard (James Leonard’s father), was held in Peter Leonard’s name at a rent of £4. Old Peter Leonard, according to his son James’s own statement before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall, had occupied this cot since 1823. James also says ‘All the land was taken in long before General Burroughs came to the island’ (1848). Old Peter had sat for some years either rent free or at a merely nominal rent, which in sixty years had been gradually increased to £4. So that, at the very low rent he had so long been paying, ample time had been allowed him to recoup himself with profit at compound interest for his reclamation and improvement of the croft. Peter Leonard was a contented, sensible, and cheerful man, too honest to ask for or to expect compensation for improvements, in addition to the concession of having been permitted to hold the land at the very low rent at which he had so long held his croft. James Leonard is not his father’s oldest son, and has no claim to succeed him.

Whilst I was absent from home serving in the army, and whilst there was no resident factor on the estate, without my permission, and without any permission that I can find any clue to from my factor, then resident in Kirkwall, James Leonard did erect a cot on his father’s croft, entirely for his own convenience, and where he lived rent free and was the better able to carry out his trades of mason and weaver. His father never lived in this cot with him, but lived in a separate house on the croft. When declining to accept James as a tenant, after his saying that he always opposed me and would oppose me to death, &c. &c. (as stated in my letter of the 13th October), although in no wise bound to recompense him (as admitted by himself in his evidence before the Royal Commission) for this structure, erected in defiance of the estate rules. I had it valued by two neutral persons, the one chosen by him and the other by me, and the price they appraised, what under other circumstances might have been due to James Leonard, amounting to about £26, I paid him. The donation of this compensation James Leonard twists into an acknowledgement from me of his being my tenant. I may here mention that no less than some fifteen persons – sons, daughters, and grandchildren of old Peter Leonard – under one pretence and another, were living on this eight acre croft of Digro at the time of his death. This could not have continued. I therefore declined to permit James, the mason and weaver, who was best able to provide for himself and his family elsewhere, to remain there. The others are there still.

James Grieve’s case is explained in my letter of the 13th October. He, too, never held land from me. He misleadingly states in the so-called supplementary statement that he had ‘paid rent regularly.’ The only payments he ever paid me were for the privilege of cutting fuel peats from the moss near his brother’s farm, where he was living; and these payments he paid very irregularly, and gave my factor much trouble in collecting them.

Under these circumstances, I would beg leave to ask – Would any one placed as I have been have acted differently? Had any one a candidate for a tenancy under him, or even a tenant, who told him that he had been opposed to him always, and would oppose him to death; and, in addition to this, were he to receive an anonymous letter threatening him with death if he declined to accept such a person as his tenant; would he, I ask, be intimidated into compliance? And, if so, in what state would the condition of affairs soon be? Not only have I, since last July, been thus threatened, but, seeing that the threat was lost upon me, an anonymous letter bearing the Kirkwall postmark, 20th September 1883, was sent to my wife (as if from her old housemaid, now Mrs James Grieve) threatening us with ‘the darkest page in Orkney history’ (which has some very dark pages) if she did not remove me and all Caithness men and strangers out of the island. I have no doubt in my own mind who were the writers of these two letters, but I have not yet sufficient legal evidence to convict them.

I am accused of bringing ‘landlord terrorism’ to bear upon my tenants to induce them to sign a memorial in my favour, whilst my guests with their children at a school feast which my wife has been in the habit of giving yearly to the school children. This is of a piece with other equally unfounded charges brought against me. My wife, whose one idea has always been to do good and to make happy all around her, was so hurt at the wicked and untruthful statements made by the so-called ‘delegates’ before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall, on behalf, as they said, of all my tenants, that she had resolved not to take any trouble on their account any more, and declined to give the children’s party. It was only after the many kindly greetings we received from all we met in Rousay, after our return from a short visit to Germany, and the many assurances they gave us that they had no sympathy with the agitators, and that what they said neither represented the feelings of the inhabitants of, nor had any weight in, our island community; and that the disappointment to the children would be punishing the innocent many for the discontented few, that she relented from her resolve and gave the party. She, however, purposely abstained from inviting a single parent, feeling that if the sentiments promulgated by the ‘delegates’ were shared in, as they affirmed, by the body of our tenantry, many of the usual faces seen at our former parties would probably be absent. A much larger number than usual of grown-up people did, however, appear at this party, and by their friendliness gave us to understand that they had come to show their goodwill towards us. The party went off very cheerfully. Its so doing, we were afterwards informed, was a fresh cause of offence to the agitators.

One of the principal tenants, after a meeting of the district road committee held that morning in my house, where, in the absence of any public committee room in the island, such meetings always have been held, did start a paper stating that the so-called delegates did not in any way represent the signatories of the paper. This paper was, I am told, taken round by our friends for signature, but was not numerously signed, from fear of the vengeance of the agitators; and to such an extent was this carried that, as stated in the so-called ‘supplementary statement,’ ‘nobody could be got there’ (in Sourin, in the neighbourhood of the Free Church manse)’ to take the thing round for signatures. Threats of vengeance and of destruction to stock, crop, and property were dealt out by the agitators, and this in an island ten miles by sea from the nearest policeman. The effect of this was that the peaceful and law-abiding, who had personally assured us of their disavowal of all connection with the delegates, withheld their signatures from the document for fear of the persecution and terrorism of the disorderly. To such a pitch had this attempt to establish a reign of terror in this hitherto quiet and peaceful island come to that the schoolmaster, the copy-books of whose scholars had been examined by the authorities in connection with the anonymous letters, and who had been south to get married, and who had now returned with his bride, was met at the landing-place by a party of roughs, who hooted and howled at them, and who also threatened with their vengeance the farmer who sent his carts to cart up their furniture and baggage from the shore to the schoolhouse. The school premises were damaged, and the inspector of poor, who had also befriended the teacher, was nightly subjected to their annoyance. A part of his enclosure dyke was knocked down, and his fishing-boat was broken. On hearing of this, I immediately personally visited the district, and called at the houses of the parents of the disorderly young men who had been led astray to break the peace, and I told the parents I would hold them responsible for the misdeeds of their dependants. I annex a copy (Enclosure 1) of a letter I wrote to a young man on this subject; and I am glad to say I have heard of no more disturbances since.

The signal failure that has attended the efforts of the agitators to continue to disturb the peace of the community shows the good sense of the great body of my tenantry, who, with the exception of a few in the vicinity of the Free Church manse, have stood aloof from this noisy strife. The so-called ‘evicted delegates’ have met with no sympathy in the island of Rousay, nor in the county of Orkney, where the true circumstances of their case are known. I have, therefore, no reason to alter the assertion I made before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall, that the delegates did not represent the sentiments of the great body of my tenantry. I sent to the chairman of the Royal Commission on the 19th September 1883 the following correction to my evidence in Kirkwall in respect to the farm of Westness and Quandale, viz., ‘The cots in Quandale and Westness which formerly (1842) brought in £75. 15s. plus £64. 16s. 9d., or, together. £141. 11s. 9d., after being consolidated into one farm, and after having had about 1500 acres of hill pasture added thereto, and after an expenditure of more than £3000 thereon (for building, dykeing, and draining), now bring in a rent of £600 a year.’ I at the same time corrected a calculation made by Mr Fraser-Mackintosh, that ‘about £17,000 was spent on my house.’ The correct amount expended on my house and grounds (in building, furnishing, and laying out) up to the end of 1882 was £11,690. 3s. 3½ d., which is some £5300 less than stated by him. In paragraph 3 of the so-called ‘supplementary statement,’ I am charged with having caused the undemoted so-called ‘evictions,’ viz.: –

1. Edward Louttit. – I never even heard of this case before.

2. James Sabiston. – He had a lease from me in the island of Veira. At the expiry of his lease he declined a new lease.

3. Thomas Sinclair. – He agreed to rent from me the meal-mill of Sourin, together with the small farm of Hurtiso, on the understanding that his father was to start him in the concern. His father resiled from so doing, and the son had to give it up. Thomas is now living with his father in Rousay.

4. Widow Gibson (Langskaill). – Two brothers Gibson conjointly held this farm, and were, although on the best of terms, in one another’s way. One brother was drowned, and left his widow in very comfortable circumstances. At the expiration of the lease I renewed it with the surviving brother. The widow and her grown-up son took a large farm in another parish.

5. Hugh Inkster (Hammer) is a sickly man, unable, he says, to work, and consequently unable to cultivate his farm. He refused to pay school fees, and assaulted a teacher who asked for them. I left him in his house, and gave his land to another who was able to cultivate it. His wife brought his case before the Royal Commission at Kirkwall.

6. William Louttit (Faraclett). – His lease expired, and he declined a new lease.

None of the above cases are what are usually understood under the term ‘eviction’; nor has there, to my recollection, been a single case of eviction since I succeeded to the estate; nor was there in my grand-uncle’s time before me, for any person he removed he offered another place to.

Paragraph 4 of the so-called ‘supplementary statement’ is a tissue of mis-statements. Its writer says – ‘We would like to hear General Burroughs on this question of the poor and the roads.’ I accordingly append hereto (Enclosure 2) a tabular statement of the sums annually assessed and expended on account of the Rousay district roads, from 1841 to 1883, by which it will be seen that I have paid £510. 11s. 3d. in excess of my assessments. I have also at my own expense built a private pier, which is freely used by all, and which cost me some £640. During the same period there has been no poor assessment on the parish, but the poor of Rousay and Veira have been supported by me; and besides free houses and fuel, and in some cases land to cultivate, they have received in money payments, through the inspector of the poor, some £3100. The poor in this, as in other parishes, have been relieved according to their needs and their ability towards contributing to their own livelihood. I am now accused of giving to the poor ‘a sheer starvation rate of support!’ The best answer to this is that no valid complaint, that I can remember, has ever been made to the Board of Supervision of inadequate relief. Had there been any just cause of complaint, no amount of landlord terrorism would have stood in the way of its being published trumpet-tongued to the world. However, as the agitators are not pleased with the present arrangement, which they say ‘is indeed a very fine arrangement for General Burroughs,’ I have declined to continue it, and I have applied to the Board of Supervision to have henceforth a legal assessment imposed upon the parish for the support of the poor.

Paragraph 5 purports to give ‘a special instance of the way in which the support of General Burroughs’s poor is managed’ in the case of ‘George Flaws, a poor, afflicted, but very deserving man at Frotoft in Rousay.’ The statement regarding this poor man is very misleading and dishonest. G. Flaws was not a pauper at the time the subscription was got up for him. I was then in Germany. I heard from the inspector of poor of G. Flaws’s case, and that he had no wish to have his name entered on the roll of paupers; that he had stated, when called upon by the inspector, that ‘he still had of his own to do his turn.’ The inspector gave Flaws £1 from me to add to his own. He had been, when in health, an obliging man and a good tradesman, and very popular, and I understand that his friends did raise a subscription for him. This subscription was not originated either by my factor or myself, but by a fanner in Rousay. G. Flaws is alive, and able to state his own case.

Paragraphs 1 and 6 are so mixed up together that I have replied to them at the commencement of this letter. The long leases my tenants have enjoyed at low rents, and the amount of money that has been expended on estate improvements, as detailed in the ‘Memoranda of the extent of farms, their rental, and the sums expended upon them, and on the estates of Rousay and Veira generally, in way of improvements, from 1840 to 1882,’ as handed in by me to the Royal Commissioners at their meeting in Kirkwall, will, I think, fully confute any accusation of over-renting, and of want of compensation for improvements.

Paragraph 7 says that ‘General Burroughs tries to create an impression that the Church and the influence of the ministers in Rousay raised the crofter movement, especially that of the Rev. A. MacCallum of the Free Church in Rousay.’ From the inquiries I have made, and from all I have heard, the impression, I regret to say, has been forced upon my mind that the last and the present Free Church minister in the parish have not been unconnected with this crofter movement.

Paragraph 7 also states that General Burroughs ‘had only too many complaints and disturbances long before the Commission. Such were the disturbances, as was stated in the evidence, that both he and his factor went together and repeatedly visited his tenants to secure quiet; and his law agent, the procurator-fiscal, Mr Macrae of Kirkwall, did the same, but with little success. General Burroughs then wrote to Mr MacCallum to visit his tenants. It was by this act of General Burroughs himself that Mr MacCallum was first asked to intervene. And General Burroughs, by stating in his letter that, if quiet did not ensue, the sub-tenants would have to be removed, intimated that it was the arrangement of the land that was the cause of dissatisfaction and disturbance.’ The truth of this much distorted statement is, as I stated in my evidence before the Royal Commission in Kirkwall, that a quarrel took place in the district of Wasbister (Rousay) between a farmer’s wife and the sister of another farmer. I was appealed to as a justice of the peace by the farmer’s wife, and had almost succeeded in making peace between them. I also wrote to Mr MacCallum, as they were members of his congregation, and asked him to call upon them. After this visit the matter got worse, and it was ultimately brought before the sheriff-substitute; and although decided by him, a considerable amount of ill feeling survived, and this was shown in various spiteful acts. The husband of the farmer’s wife complained to me of certain cottars, his sub-tenants, who, he said, had sided against his wife, who is a stranger to the county, and had been very rude to her. I considered the cottars were to blame; and I told them that if they could not live at peace with their neighbours they would have to remove. As before said, the case was dealt with by the sheriff-substitute, and a record of it will be found in Court-books.

The remaining paragraphs of the so-called ‘supplementary statement’ are attacks upon others rather than upon me; and I have no doubt they will be able to give satisfactory explanations of them. In conclusion, I would beg to say that only about three years ago, when I returned home after a short absence, during which I had been promoted to be a major-general, a large body of my tenants welcomed me on my landing at Trumbland Pier (Rousay), and presented me with an address of congratulation on my ‘well-earned promotion,’ and they expressed the hope that I was now about to retire from war’s alarms, and quietly settle down for the rest of my life at home. They took the horses out of my carriage, and dragged it up the avenue to my house. Nothing in the interval between that time and the visit of the Royal Commission to Orkney had occurred to disturb the good feeling then subsisting between my tenants and myself. I left home in the winter of 1882-83, and paid a visit to the Continent. On my return in July 1883, to my very great surprise, I found myself suddenly and unexpectedly assailed in the very spiteful manner in which I was attacked by certain so-called delegates before the Royal Commission. The more I have inquired into this agitation, the more convinced I am that it is an exotic product which has been fostered into growth by the unscrupulous agency of outside agitators.

F. BURROUGHS, Lieut-General

ENCLOSURE 1.

Copy of a letter (omitting persons’ names) addressed to a Young Man, on the subject of attempting to establish a Reign of Terror in the District of Sourin, Rousay, Orkney, N.B., by Lieut-General F.W.T. Burroughs.

Trumbland, Rousay.

General Burroughs has received Mr X’s note of the 8th inst. He is as much surprised and grieved as Mr X says he himself is to think that Mr X has made the mistake of taking himself for another, for General Burroughs never mentioned Mr X’s name when he called at Y. His visit was a friendly one to Mr X’s father, for whom be entertains much respect and regard, to warn him ere too late to prevent any of his sons getting into trouble. For the very disgraceful proceedings at the arrival of Mr X with his newly-married bride had reached General Burroughs’s ears, and he had seen the damage that had been done by night to the school premises. He had heard that the young bride’s first exclamation on landing at Sourin and experiencing the very savage treatment she and her husband met with was, ‘Where have you brought me to?’ And well she might. If she writes to her friends in the south, which she probably has already done, and describes her first landing at Sourin, her friends might be excused in imagining that her husband had taken her off to Owyhee, where Captain Cook was murdered, and where they eat missionaries, instead of to one of the group of the islands constituting Great Britain. General Burroughs was very sorry to hear that one of Mr X’s sons was mixed up in this disgraceful affair. Just imagine if any of the people of Rousay when they go south were to experience on landing in Caithness, or at Aberdeen, Glasgow, or Leith, the treatment they accorded to Mrs X where would they think they had got to? And when people in the south hear how in Rousay they treat strangers arriving amongst them, it will raise very angry feelings towards them when going south to better themselves they arrive elsewhere as strangers. General Burroughs is very glad to hear that Mr X took no part in the late disgraceful scenes, and he hopes that none but the very foolish did so. It is General Burroughs’s duty as a justice of the peace to take notice of all irregularities occurring in Rousay; and in the execution of this duty, and for the peace and comfort of all the respectable residents in the parish, he will leave no stone unturned to bring delinquents to well-merited punishment, and he looks to Mr X and to all the respectable members of the community to do their duty by aiding him to do his. It is only by preserving peace and goodwill amongst the community generally that it can prosper. Those who stir up strife amongst us do so, however disguised their motives, to serve their own selfish ends, and bring misfortune upon their dupes. General Burroughs is very glad to hear that Mr X has no sympathy with such men.

10th October 1883.

N.B. – This letter was in reply to one from another son of the same man, who, to shield his brother, had cunningly saddled himself with the offence.

F. W. T. B.

Statement by John Macrae, Esq., Procurator-Fiscal, Orkney.

Kirkwall, Orkney, 8th January 1884.

I wrote you on the 19th ult. acknowledging receipt of your letter of the 17th forwarding proof of a statement to the Royal Commission (Highlands and Islands) by Mr James Leonard, and requesting any observations thereon which I might be disposed to offer. I stated that I would avail myself as early as possible of the opportunity afforded to me by the Commissioners. In now doing so, I shall confine my observations to the 7th, 8th, and 9th heads of the statement, being the heads in which my name appears.

In the 7th head it is stated that ‘such were the disturbances, as was stated in the evidence, that both he (General Burroughs) and his factor went together and repeatedly visited tenants to secure quiet, and his law agent, the procurator-fiscal, Mr Macrae of Kirkwall, did the same.’ I beg to inform the Commissioners that, as regards myself, the statement is not true. I never did visit, or was asked to visit, tenants to secure quiet. A precognition was taken in Rousay on 6th September 1881, under a warrant granted by the sheriff upon a petition at my instance as procurator-fiscal, with reference to a charge lodged by one female against another of assault by throwing dirty water; and upon the 30th September 1882 another precognition was taken in the island, under a similar warrant, with reference to a charge of malicious mischief, consisting of injuries done to a reaping machine and some scythes which had been left over Sunday in a hold adjacent to the public road. Neither of these cases disclosed any disturbance among the tenantry upon the estate. The case of assault arose out of a disputed right of footpath. The other was of a class that is not uncommon, when opportunity occurs, although it was the only case of the kind that had occurred in Rousay since 1873. The precognitions in both cases were, in usual course, submitted to the sheriff-substitute, who, in the case of assault, directed the accused to be tried summarily; and in the case of malicious mischief ordered no further proceedings, the evidence being insufficient.

With reference to the 8th head of the statement, I beg to inform the Commissioners that I acted as factor for General Burroughs for the period from 7th April 1874 down to the end of 1875. My predecessor was the late Mr Scarth of Binscarth, who acted as factor upon the property for about thirty years. When I became factor the whole farms and crofts upon the estate were, with a few exceptions, held under leases or sets for periods of years – the shortest period being seven years. It is untrue to say that there were then, or during the time that I was factor, ‘complaints strong and numerous about high rents.’ I should be much surprised if there had been, as Mr Scarth, who arranged the rents, was a proprietor and farmer himself, as well as factor upon various other estates in Orkney, and his sympathy with, and encouragement, in many substantial ways, of the tenant-farmers upon the estates of which he had charge, are well known. It is not true that General Burroughs spoke to me, either before or during the time that I was factor, about complaints being made to him that the rental had been too high; neither is it true that I visited any of the tenants or made any inspection of their holdings in consequence of such complaints.

When General Burroughs requested me to accept of the factorship after Mr Scarth’s retirement, I felt, and Mr Scarth concurred with me, that I could only manage the estate efficiently at a distance, by acquiring a minute acquaintance with the various holdings. Accordingly, of my own accord, I, in April 1874, immediately after my appointment, spent several days in inspecting farms, taking those first that might sooner require my attention than others. I continued this inspection during part of the months of September and December 1874, and would have gone on and completed my inspection of the whole farms if it had not become apparent that it would be prudent for General Burroughs to have a resident factor; and accordingly, in the summer of 1875, the present resident factor was engaged, and entered upon his duties towards the close of the year.

I do not remember the whole circumstances in connection with my inspection, but I can recall enough to enable me to state to the Commissioners, as I now do, that some of the details professed to be given in the statement are untrue, and that others are grotesque distortions or perversions of facts. If the Commissioners should desire it, I shall, from the recollections of the tenants whose farms were visited, and of General Burroughs and myself, compile a statement of the circumstances which, I should hope, would have at least the merit of being accurate. In matters of arrangement between proprietors and their tenants I have striven to keep steadily in view that their interests are in the main identical, and that a proprietor who wishes his farms well cultivated must take care that the tenants are not only suitable, but that they should have their farms at rents which will enable them to live comfortably and save something. It is only a matter of simple justice to the Orkney proprietors to say that they are fully alive to this, and, so far as I can speak from experience, they have not, on the whole, been unsuccessful in applying the rule.

I observe that the writer of the statement suggests that proprietors should not have the power of availing themselves, if they think fit, of the professional services of the person who may hold the office of procurator-fiscal. It is not proposed that tenants or any others should be deprived of this power, so I might let the suggestion pass. I can say, without boasting, that to more tenants in Orkney than proprietors, do I act as professional adviser, and that not a few of these are tenants in Rousay.

It may not, however, be out of place for me to refer the Commission to the fifth report of the Commissioners appointed in 1868 to inquire into the Courts of Law in Scotland. On page 45 of this report, the Commissioners state that they ‘approve of the mode in which these officials (procurators-fiscal) are appointed, and the conditions on which they hold office.’ They further state that a majority of them ‘do not concur in the suggestion that the procurators-fiscal should be prohibited from private practice, and think the effect of such prohibition might not unfrequently be to prevent the public from obtaining for this important office the services of the most suitable person.’ A minority who consider that the ends of justice would be better attained if procurators-fiscal were debarred from private professional practice are at the same time persuaded that this view could only be carried out by enlarging the present rates of salary allowed to these officers, and giving them a corresponding retiring allowance.

I may also refer the Commissioners to evidence taken by the Law Courts Commissioners on the point which will be found in their minutes of evidence. By referring to the index under the heading ‘Criminal Procedure – Procurator-Fiscal’ the portions of evidence dealing with the question will readily be found. Shortly after that evidence was taken, the office of fiscal for Mid-Lothian had to be filled up, and the view that the procurator-fiscal should not be debarred from private professional practice was acted upon. I may state that my own opinion, founded upon my experience here, is, that to continue a procurator-fiscal within a range narrower even than that of a sheriff or sheriff-clerk, would, especially in counties where the duties require only a portion of his time, be very prejudicial to the public interests. He could not possibly obtain that general knowledge of circumstances which presently enables him to decide at once upon the course of investigation which he should follow in any particular case; nor would he be able to conduct the investigation with that facility, discrimination, and accurate fullness of relevant detail, which are the results of a many-sided experience. In conducting important trials he would not, on account of his limited and intermittent experience and want of general forensic practice, be able to cope with lawyers in daily practice in matters civil as well as criminal. The result would be that a feeling of contempt for the administrators of the law would grow up in the minds of that section of the community whom it is desirable to impress with a wholesome fear of the criminal law, and with a sense of the efficiency of those who are called upon to administer it.

As pointed out by the Law Courts Commissioners in their fourth report, p. 21, the sheriff is the executive officer in matters criminal and the chief executive magistrate in every county; and in this county either the sheriff or the sheriff-substitute take the direction of investigation into crime of all classes, and dispose of all cases that may arise, determining whether there should or should not be criminal proceedings adopted; and, if criminal proceedings are to be adopted, whether the case should be tried summarily or reported to crown counsel. There is therefore no room for the procurator-fiscal to exercise any partiality, even if he were so disposed.

With reference to the 9th head of the statement, I may state that I acted under the immediate direction of the sheriff of the county, and under warrants granted by him, in consequence of a letter in the following terms having been submitted to him: –

‘General Boroughs, – Sir, I havee Noticed in the Papers that you are determined to Remove these Men that give Evidance to the Comission in Kirkwall well if you do as Sure as there is a God in Heaven if you remove one of them there Shall be Blood Shed for if I Meet you Night or day or any where that I get a Ball to Bare on you, Curs your Blody head if it dose Not Stand its chance, thire is More than me intended nail you you are only a divel and it is him you will xo and the Sooner the Bitter and if you Should leave the Island if it Should be years to the time you Shall have it O Curs your Bloody head if you dont you divel the Curse of the Poor and the amighty be on you and if he dos not take you away you Shall go So you can Persist or Not if you chuse but be sure of this you shall go I State No time but the first Convenianc after there removal.’

I am not at liberty to enter into the particulars which the precognition taken disclosed, but I may state generally –

(1) that a formal written complaint of the crime of writing and sending a threatening letter was, along with the letter and the envelope thereof bearing the Rousay postmark only, lodged, which necessitated the action of the sheriff in the matter.

(2) That that complaint was laid in due course before the sheriff, who happened to be in the islands at the time, and who granted the usual warrant for summoning witnesses to be precognosced. He intimated that he would (as he did) superintend the precognition himself and dispose of the case.

(3) That to carry the sheriff, sheriff officer (who happened to be also the superintendent of police), and myself and clerk as soon as possible to the Island of Rousay, the sheriff, who was sending the ‘Firm’ to Zetland on business of the Fishery Board of Scotland, arranged that we should start by early on the morning of the 16th August 1883, and be dropped by her en route which was done, and she proceeded to Zetland. No other means of expeditious conveyance could have been secured, and it attained the sheriffs object of reaching the island, and getting what information he could, without the visit and its object becoming known, as it otherwise would.

(4) That Frederick Leonard was not arrested, but sent for and voluntarily accompanied the messenger to my presence. He was precognosced by me in the public school where the other witnesses were precognosced. If he had been arrested, it would have been my duty to have had him taken forthwith before the sheriff for examination, which would have been done, as the sheriff was at the time in the island.

(5) The sheriff, after considering the precognitions, granted warrant for the apprehension of Samuel Mainland, and for his being brought before him for examination next day at Kirkwall; and Grant the officer, with this warrant in his possession, went off immediately and apprehended Mainland in Stronsay.

(6) I am informed by Grant, the officer who apprehended Samuel Mainland, that Mainland was offered and partook of food, consisting of herrings, oat bread, biscuits, and tea, along with himself and the boatmen while on the voyage to Kirkwall, and that on his arrival at Kirkwall he was offered but refused to partake of any food. I have no reason to doubt the accuracy of the officer’s statement. He is a most reliable and experienced officer, and I have always found him very considerate and humane in his treatment of prisoners. In the case of Mainland, the officer further says, that after taking the boy to Kirkwall, instead of placing him in a cell, he allowed him to sleep all night with a brother in his lodgings.

(7) The sheriff, to avoid Mainland’s detention longer than was necessary for the ends of justice, himself took the young man’s declaration at 10 o’clock A.M. next day, and, after considering it, and the precognition taken, liberated him. Everything was done as expeditiously as possible, and in ordinary course. Mainland’s expenses back to Stronsay could not be paid under the rules which obtain at Exchequer.

(8) The sheriff, before leaving for the south, instructed the sheriff-substitute to continue inquiries as to the charge. Hence I made other two visits to Rousay, and it was in consequence of a statement made by the Rev. Mr MacCallum bearing upon the crime which was under investigation, that it became my duty to precognosce him and did so.

[That concludes the proceedings, and subsequent correspondence]