Eynhallow has some strange beckoning power in that green face of springy turf, even to the most unromantic mind. Around its shores, the restless, heaving sea forever rolls, and to the north-west it looks out upon the vast, endless unbroken ocean. Small wonder that here first came the Culdee monks when on their great mission, and who can blame the simple sons of the sea for having created around it a web of mystery and inspiration. Here seems to rest the very spirit of Orkney’s Norse glory.

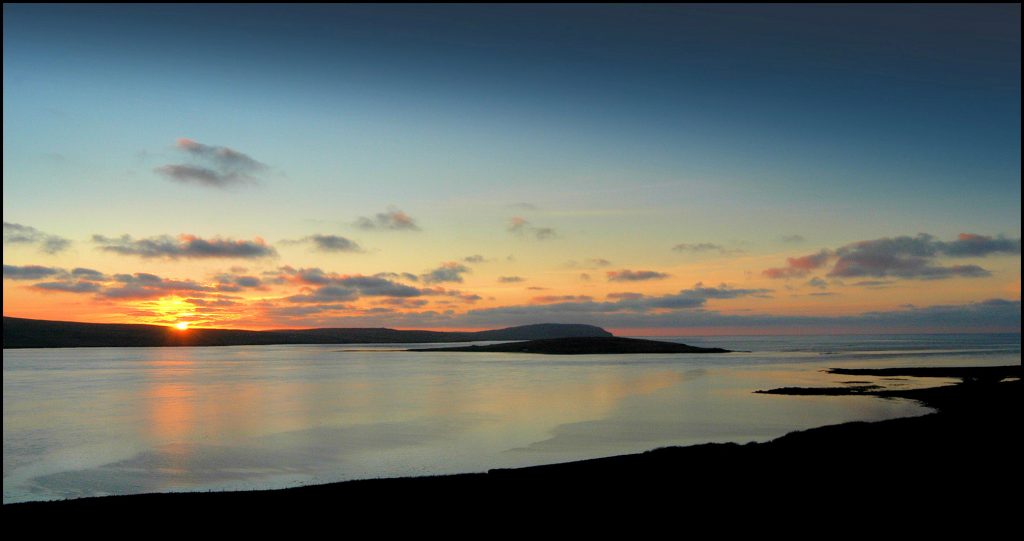

There lives in my memory a summer night of long ago, spent around its shores in the boat of two friends who were tending their creels. That was before the days when the Orkney fishermen had a motor in his boat; then a night spent in the open was no more to him than sleeping in bed at home. At that time Orkney lived on the sea and made ends meet by a little help from the land and the sea-shore. I can still see, in memory’s eye, those two lusty sons of the sea pulling their yawl to the grounds while the breathless night was beginning to brood on land and sea. I should not say night, because there was very little of that in the usual sense of the word, but the quietness, broken only by the steady rhythm of the oars and the swish of water under the boat’s prows, combined with that multi-coloured setting sun in the north-west to produce an effect equal to the fastness of the deepest sleep. Nature was going to rest. Not a breath stirred the surface of the sea as it glided outwards in the ebbing tide like some phantom ghost until it had its usual revel in Burgar Roost.

At last we neared Eynhallow, and, with skilful hands, the fishermen guided their small craft between its rocks on the one hand and Burgar Roost on the other. In a short time we were up with the first lot of crabs in a small bay almost at the headland on the north-west corner of the island, known as the Spur. There at varying distances from the main current of the tide I could see the bobbing corks and tarred ropes which betrayed the position of the creels. One of the men left the oars, and, having put on his oilskins to protect him from the dripping lines, took up his position in the stern of the boat and waited until his comrade brought her alongside the first buoy rope. Up and up, with strong arms he pulled that creel to the surface, bringing in it, a lovely lobster. “Ah! my bonnie boy, right gled are we tae see ye. May mair o’ yer kind come along this sam’ night.” Thus it was welcomed by his captor into the boat. And then the fisherman lapsed into silence – his innate silence produced by his continual contact with the big things of life, the earth, air, sea, and sky and Nature in her every mood.

After a short time the creels at that point had all been hauled and baited, and, noiselessly, the fishermen resumed their positions at the oars and began to pull to the north side of Eynhallow. Here the bold cliffs and deep caverns ring with the sound of lashing foam on a rough day. Beneath these black, austere masses of rocks, the sea lay as calm and peaceful as if it feared to break the silence of Nature. In a cave here, known as the Twenty Man Hole, the men of the surrounding districts used to find shelter from the ruthless raids of the press-gang whenever news of a raid was voiced abroad.

With few remarks the fishermen rounded their creels and pulled on around the Bowcheek, a dangerous headland when any sea is running, into Eynhallow’s only bay of importance, Ramnageo. Here is one of the most lovely bays in Orkney. The land terminates, here in cliffs, there in lovely round stones of all colours and sizes, while the water around is as clear as shining crystals. On the bottom one can see the long seaweed bending to the ever restless tide like willows in the wind. Many a good catch of lobsters has been won in this quiet haven, and it is still one of the best places for lobsters around the island.

In this quiet haven we lay for about two hours. The fishermen were only going to haul their creels twice that night, and consequently wished to give them a good long stand as they called it. Lying there in the stillness of the wide open spaces, a strange feeling came over me. What it was I cannot say, but there appeared to be some new element creeping into my soul, the call of the sea and the wide open spaces of those charming isles was singing its lovely notes in my ears, and who of Orkney blood can afford to forget that call that comes to every one of us in these wind-swept islands?

There was the moon casting its golden shades from behind a heather-clad hill in Rousay out upon Eynhallow and the ocean beyond. As I looked at that golden thread of light upon the glistening water, I realised that the Orcadian lobster fisher, poor though he may be, experiences incidents and sees Nature consummate in such a manner as to repay him for all his troubles. These alone keep him forever tied to his homely croft, his boat and fishing gear, and above all to the restless, roaming, heaving sea.

For a sense of perspective see the soaring whitemaa, lower right.]

In scenes such as these has our race kindled that spirit which has made it predominant in many walks of life. These scenes have aroused poets to tune their songs, and in days gone by they captivated the roaming Norseman and induced him to apply his energies no longer to war but to the simple arts of peace. – P.

Extracted from the Orkney Herald, December 21st 1938

© British Newspaper Archive