The first of a four-part article

written by Tommy Gibson, Brinola, Rousay

Sourin is the largest of all the districts in Rousay. In the 1841 census 316 persons lived in 74 households compared with today (2003) with only 65 in 29 households. I remember about 1956-7 about 120 folk in Sourin. The terracing on the eastside of Kierfea at 762 feet, and the Head of Faraclett 341 feet, is very noticeable when coming into Sourin from the South. This was due to the ice age. The traditional divisions are to the south is the Red Road, or Kirk Brae, and to the north, the Council dump at the top of the Leean, and from Scockness up the Sourin Valley to the west. The different districts divisions in the hill are not very well defined. Sourin as its name suggests had a lot of sour wetland, especially under the north side of the hill of Knitchen. Sourin also boasts some excellent dry fertile land, with some of the best land in Sourin on the steepest fields. Traditionally the Blossan, or Hammermugly, at 455 feet was the highest elevated house lived in, in Orkney. Blackhammer in Wasbister is about the same elevation. Sourin is surrounded on three sides by hills.

To the east is the sea. If anyone stops on the public road below Hammermugly, they have before them the very best view in Orkney. This is from the Noup Head, Westray to Deerness to the south. All the north Isles and countless holms and skerries. On a very clear day, usually in summer time, Fair Isle can be seen over the Red Head, Eday. Foula can be seen over Papa Westray. Foula is on the same latitude as Lerwick but I have never seen any part of the Shetland mainland on the horizon. In the days of herring fishing out to the east of Orkney, fishing boats coming back, could not distinguish the Islands and Kierfea, being one of the highest points and was known as Culldee Hill, was one of the points of navigation.

the northern tip of Egilsay; the Westray/Stronsay Firth; the southern tip of Eday;

and the western coast of Stronsay in the distance

The Mill

The Sourin Mill is a large well-built stone building of three storeys, situated at the end of the Sourin burn near Lopness and Nethermill. This was the largest building in Sourin, and today still stands as straight and square as it was when it was built. On the west end of the building four plaques have the dates of 1777, 1861,1880 1937. The first date is presumably when the building was constructed. It is not known if there was a mill there before, and I doubt if there were. The wheel on the east end of the mill is a cast iron construction, and was made in sections. The wheel was 14 feet in diameter, and 4 feet across with 48 buckets. The axel, holding everything up, was 5 inches of solid steel. The arrangement at the wheel for the water was overshot, this was quite a powerful wheel to drive all the equipment, which were three sets of grinding wheels. The first one was for bere meal; the stone was from Derbyshire, called Derby Burr. The oatmeal stone was manufactured; it was made in sections and then banded with iron hoops, called a French Burr. The shelling stone usually came from Yesnaby in Sandwick. Also the hoist; this was to lift the sacks of grain to the top of the mill, and elevators and separators and fans. The water driving the wheel came from the Muckle Water, with a small dam that was built at Woo. A ditch was dug from the dam to the wheel above the burn to the mill course as the wheel was overshot. A wooden trap in the mill course diverted and governed the amount of water to and from the wheel. In the 1940’s a small shed was built at the rear of the mill.

This was a room to house a small dynamo driven by a small water wheel, to provide electric light in the mill. The only light was from paraffin lamps, and this was the only light used since the mill was built. Before the days of the mill, most of the houses had a kiln attached to the barn, which the corn and oats for drying was done. After the mill was built, a lot of drying was still done but then the grain was sent to the mill. This practice was continued up to the 1850’s, then more and more grain sent to the mill undryed. The kiln at the mill became too small, and in 1861 a larger kiln was built. This was slightly wider than the mill and slightly higher. This increased the floor area for grain drying. I have no record for 1880, but there must have been some structural work taken place. In 1937 the kiln took fire. The roof of the kiln was badly damaged and the mill was out of production for a while. Had the fire gone into the main building the whole lot would have been destroyed. There is a tremendous amount of timber in the mill. Heavy beams under the floor, holding up untold tons of grain, huge beams, a foot square holding up the hoist mechanism, which is housed in a wooden structure in front of the mill. Repairs to the kiln and a new roof was put on and the mill started up again.

The miller, or his son or servant, had to walk up to the tepping (sluice) early on a Monday morning to open the sluice as it took a few hours for the water to flow down. This water ran till Saturday when it was closed in the afternoon. The water ran on till 9-10 o’clock when the mill closed for the day. Only in the springtime when the water was not so plentiful that the sluice was closed every afternoon. The miller usually worked for 14 hours a day and six days a week and usually employed a kiln man and at busy times a labourer. On the average working day the mill ground 25 sacks of oats and 22 sacks of corn or bere. A sack of grain was 2 cwt, this was traditionally the correct weight for the mill, and the meal came in how (boll) sacks. A boll was 10 stone.

Corn or bere had only two rows of grain while barley has four. Long ago it was mainly black oats and red sandy; it was only in later years that heavier oats were available. The best yield was from the smaller oats. Products from the mill were oatmeal, bere meal, grapp and souan sids. Grapp was an inferior grade of grain and hull, ground for pig and poultry feed. Souan sids, was when the flour was riddled small bits of husk and the finest flour was gathered up. This was then soaked and made into a sharp porridge. I remember in the mid 1950’s Robbie Seatter of Banks had a square of corn growing in a field above the mill. The area was about half an acre, and this was about the last of the corn grown in Rousay for the Sourin mill.

Each sack of grain weighed 2 cwt. each. This was traditionally the correct weights for the mill. Carts which came to the mill with grain usually went under the hatch in front of the mill. The grain was then lifted to the top of the mill by a hoist. Once the hoist was engaged the sack had to travel to the top of the mill. A chain with a loop was then put around the sack. Once a farmer put the chain around the sack, and unfortunately the hoist was engaged before his fingers were out of the chain. The miller looked down when he heard shouting. “Woe, woe, stop, stop,” the farmer was coming up holding on very, very tightly to the sack! The Sourin mill took most of the grain in Rousay. In the springtime when the weather dried, the Sourin mill had plenty of water and grain came from Westray, Eday, North Fara, Egilshay and Wyre. When the North Fara men came to the mill, they went to Hurtiso for a horse and cart to take the grain from the boat to the mill. Sometimes the horse was working, or in the hill, so they were quite happy with a cart. Fara men were big and strong: they pulled the cart themselves. Three Westray men were drowned near the Clett at Scockness. The boat was a Westray skiff, loaded with grain. Northerly wind and a back tide cause a nasty upheaval in the water along the Clett. The boat, perhaps too close to the shore, missed a tack and capsized at the shore. The mill was a meeting place for local boys from the district of an evening. Some of the more popular ones were going hand-over-hand over the twartbaeks (couple backs) in the roof. Another thing they did was to write their name on a wall using a fifty-six pound weight as a pen, hooked on their little finger and only very few of them could do this. In many ways it is a pity that the mill had to close, for it was a source of food and as a social gathering place in the evening for the people of the district, for news, views, contests and trivia etc. The mill closed down in 1955.

Peats

Sourin has a large area of peat banks, and this is situated below Blotchnie Fiold and Knitchen. Every household has a right to cut, dry and cart peats. Working in the hill, was thought by some, a pleasant job, others did not like the work. Access to this part of the hill in this area was by two roads. The lower road was past the Free Kirk, over the waddie (across the burn), past Breval and over the quagmire; this was an area of soft clay in the road where sometimes tractors and trailers mired. Tons of stones were carted there every year and tipped into road but they soon disappeared in the soft wet clay. The upper road was in by Knapper, past Curquoy then into the hill. Anyone who came out with a load of peats had right of way, carts and tractors going in to the hill had to get off the road when they met a load coming out. Every year up to about 1960, most of the Sourin men took a set day to repair both of the roads, and clean up ditches. The peat banks used by the Egilshay men was on the hill of Knitchen. The road to this hill went up past Kingerly and Clumpy. The Egilshay peats were built on a piece of land below the Gorehouse and the Geord of Banks along the shore. There are also old peat banks on the hill of Avelshay, with a road up past Classiquoy, and it is been a long time since this area was cut.

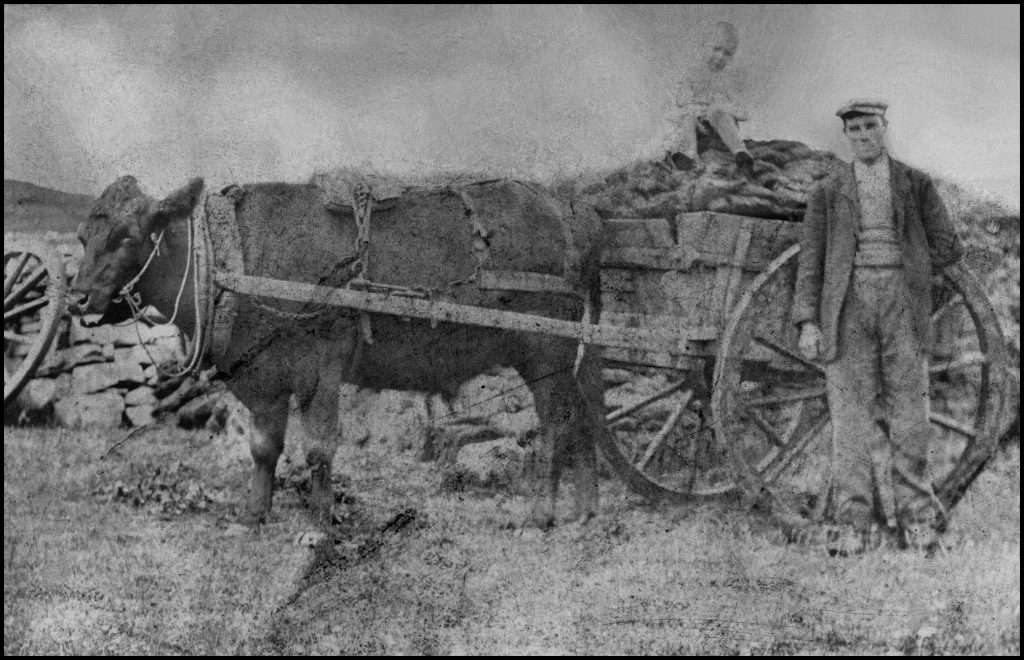

William Costie & son William carting peats back to Kingerly. c1900

The first peat banks in Rousay were on south side of the Brown Hill. The marks of the banks are still to be seen. The early peat cutters only cut the top tough moss. This was what was called “foggy” peats and when dried they carried home the dried peats on their back. The old folks thought that the black moss would not burn properly. It was less than two hundred years since they discovered that black peats were the best burning. In the days of the estate anyone needing a peat bank went to the land officer; he in turn told the gamekeeper, who set out the bank. Malcolm Hourie of Braehead was the last gamekeeper to lay off peat banks. The last bank laid off by the gamekeeper was about 1958-9. The length of a peat bank was usually governed by the state and depth of the moss at the upper end of the bank. Gock heeds, was tussock grass with roots that was nearly impossible to cut; this made banks bad to work. The width of the bank was for twenty-one years cutting. I know that there was no record of the peat banks kept in Rousay. Everyone knew their own bank, but they also knew nearly every bank in the hill. Woe betide if anyone went into the hill and cut the wrong bank. I suppose that there are not many folk alive today who know the proper location of many of the banks. Where is the banks of Digro, Swartifield, Grindleysbreck, Feelyha’? Very few folk know, most folk don’t care. The peat bank then went with a particular house. If that tenant or owner left that house, he lost the peat rights of that particular bank. When a household became empty, folk left the Island or died, and if someone asked for the use of that peat bank, they could only use that bank under sufferance. They still had no right to that bank. The house that he went to had a separate bank, and if there were any dispute, the gamekeeper was sent to sort it out.

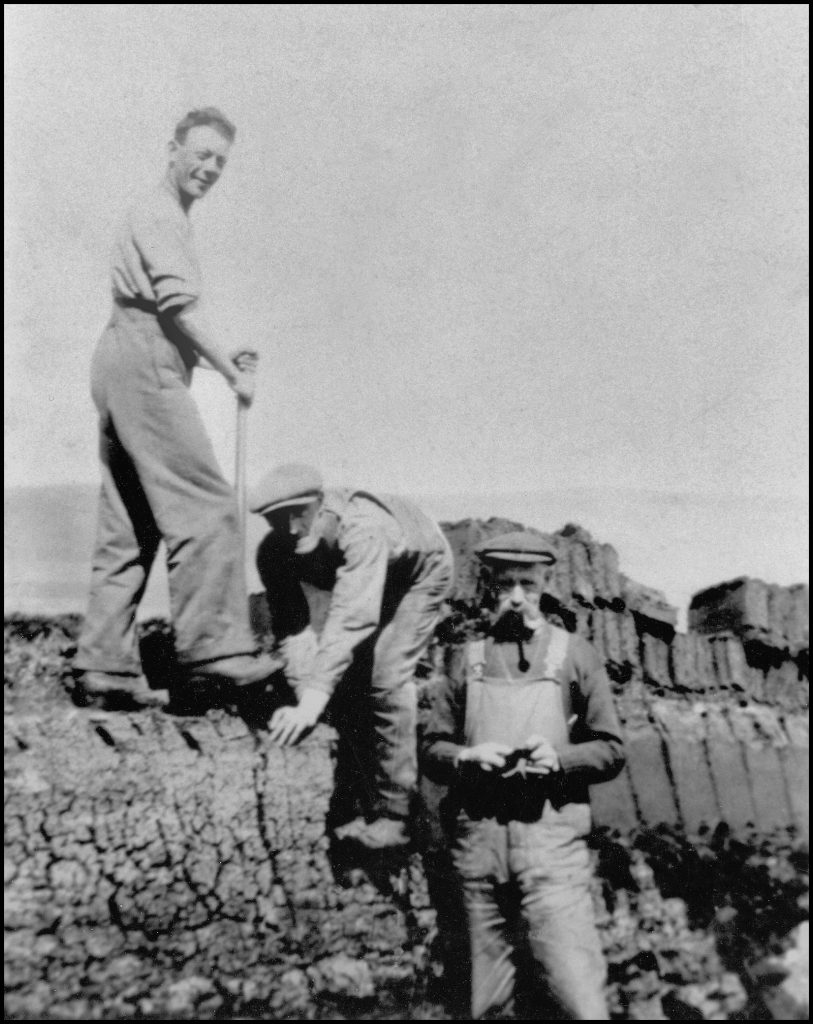

John Craigie, Breck, Jimmy Rendall, Braes,

and James William Grieve, Outerdykes

In the 1960’s folk from other districts came to the Sourin hill for peats. Some of the older men in Sourin were not pleased about this. By this time fewer and fewer folk were going to the hill and a large number of peats banks were idle. Roads to the other part of the hills were becoming impassable. If a bank had not been cut for three years, some said they could cut this bank, and by this time there were plenty of spare banks in the hill, and little attention was paid to this. A day’s work in the hill was called a “doward”, traditionally started at 7 o’clock working till 11-30. A break to 1 o’clock then finished at 6. Plenty of food and home brew ale usually went to the hill as well. In the 1930’s it was not uncommon to see 30 to 40 folk in the hill flaying, cutting or spreading peat. Long ago the men went to the hill for flaying (removing the top turf) the bank and when it came to cutting women nearly always took out the peats. This was by far the heaviest job in the hill. Women then usually did most of the work, spreading and setting up the peats to dry. In olden days women used to wear spleetos (combinations) and some did not. On a dry windy day summers day, with the ladies bending over the peats, dare I say more.

In the first half of the last century the average farm would use around 100 cartloads of peats. In Sourin the road to the hill was quite level and was not too a heavy pull on the horse. A load of peats in a cart was about 8 to 10 barrow load, again depending on the size of the horse. Some of the smaller houses only had work ox. A big work ox was extremely strong, but very slow. An ox was not as handy as a horse because it could not go backwards. The cart shafts had to be lifted over the back of its back, and if pulling a sleigh, they had to be turned into the front then hitch up. If, for example, someone living at Goarhouse went to the hill for a load of peats with an ox, on a hot day, it would take hours and hours. Some of the oxen would pull sledges piled up with peats and this was quite a heavy load. Horse and carts were about twice the speed of an ox. The roads were very busy when peat-carting time came. Farmers tried to avoid getting behind a slow work ox. Certain places along the road there were passing places and meeting places. Empty carts coming into the hill always gave way to the loaded carts going out. When the peats were finally carted a huge stack was usually built near to the house. Some of the stacks in other places were built with the peats in a herringbone effect, but in Rousay the peat’s in the stack was always built flat. With peat fires and thatched roofs, and stockyards near to the dwelling house, high winds meant sparks and hot ashes came out of the chimney on very windy nights; some houses gave a spectacular display of sparks out of the chimney. There were never any house fires or stacks burnt down due to sparks as far as I know in the parish. In the olden days the folk followed a certain code about the hill and the way they worked the hill. They went about their duties cutting the peats, spreading, setting up and carting, and if for any reason someone needed help, nearly every one rallied around. There has not been any peat’s cut in Rousay since 1999.

All black & white photos are courtesy of the author.