Two ‘sea rescues’ – the first of which involves the dramatic rescue

of a young fisherman in 1911, and secondly the retrieval of

a sum of money in 1880.

The first account was mentioned to me by Anne Paterson of Aberdeenshire. She wrote as follows: “This is about an incident in Rousay around August 1911. My father, Alfred Alexander was in Rousay for holidays and his cousin (don’t know his name) and my father were down at the shore. They saw a man in difficulties out in a rowing boat. The man had taken a fit and fell overboard. My father and his cousin swam out and brought him to shore, which saved his life. The man was a son of Sir Victor Horsley who as far as I know was there on holiday too. My father and his cousin both got beautiful gold pocket watches with chains as a thank you from Sir Victor and they were told if ever they needed any help in their lifetime to contact him. None of them did of course. My father’s watch is still to the fore. It is also beautifully inscribed on the back.”

Anne’s father Alfred was the son of James Alexander [b1848], of Cairn, Wasbister,

Rousay, and Ann Sinclair [b1849], Stennisgorn, Wasbister. They moved to

Hermisgarth, Sanday, where Alfred was born in 1893.

He attended Burness school there, and is pictured 3rd left, second back row.

[Photo courtesy of Anne Paterson]

The Orcadian newspaper of Saturday August 26th 1911, carried this report on the incident:

BOATING ACCIDENT AT ROUSAY. – A serious boating accident occurred off Sourin, Rousay, on Tuesday. From information to hand it appears that a son of Sir Victor Horsley was fishing from a small boat in this vicinity, when he fell into the sea. A lady, who was the only other occupant of the boat at the time, in the excitement of the moment, lost both oars, and was rendered powerless to offer assistance. Fortunately the accident was observed from the shore, and a rescue party set off. By this time, however, the young man had sunk, and it was only after some difficulty that he was picked up from the bottom. He was of course, now in a serious condition, and animation, our informant states, was only restored after great difficulty. It is gratifying to learn that he is now recovering.

Two months later The Orcadian revealed the name of Alfred’s cousin – Robert Sinclair of Sketquoy, Wasbister. Sir Victor was very generous in his appreciation of the two lads’ action in saving his son’s life…..

RECENT ACCIDENT AT ROUSAY. – Sir Victor Horsley has presented fine gold watches and alberts to the boys who recently saved his son from drowning. The names of the boys are, Alfred Alexander, Hermisgarth, Sanday, and Robert Sinclair, Sketquoy, Rousay. The inscription on the watches is “To (name of recipient) from Sir Victor and Lady Horsley, in grateful recollection of his prompt and kind action on the 22nd Aug., 1911.”

These photos show the watch that was presented to Rousay man Robert Sinclair, Sketquoy, for his part in saving the life of Sir Victor Horsley’s son. The timepiece has just come into the possession of James Fettiplace, who lives near Cambridge. While doing some research he came across this page on Rousay Remembered. We exchanged emails on the subject, and he has allowed me to reproduce his images.

James says the watch was just about the best you could get in 1911 – 18 carat gold, and made by one of the leading makers in London – and would have been very expensive at the time.

Subsequent research reveals the identity of the young man Alfred and Robert rescued.

He was Siward Myles Horsley, Sir Victor’s elder son.

Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley (1857 – 1916) was an accomplished scientist and professor. Married to Eldred Bramwell, they had two sons, Siward and Oswald, and one daughter, Pamela. He was knighted in 1902.

Horsley was the first neurosurgeon appointed to the National Hospital Queen Square, and was known worldwide as the ‘Father of Neurosurgery’. He was a brilliant experimentalist, elected as FRS at the age of 29 years for his work on cerebral localization and comparative anatomy. He pioneered resective neurosurgery for epilepsy, tumours, abscess, head injury, spinal and pituitary disease, and trigeminal neuralgia. He devised a stereotactic frame and a variety of new surgical techniques and technologies. He worked also on rabies, thyroid disease, vaccine, antisepsis, anaesthesia and military medicine. He was an iconoclast and social reformer, active in the Temperance Movement, a support of female suffrage, health care of the working class, vivisection and medical reform. He stood for Parliament and served as president of the British Medical Association, on the General Medical Council. He won the Gold Medal of the Royal Society, and was knighted in 1902. He worked to reform the medical services of the British Army and died on active duty, the only casualty of the First World War amongst the National Hospital senior staff.

At the time of their marriage the Horsleys lived at 80 Park Street, off Grosvenor Square, but later they removed to 25 Cavendish Square, a property previously owned by Dr CB Radcliffe and before him by Brown-Séquard. They had three children, Siward, Oswald and Pamela. Horsley was devoted to the family and was capable of working while family life went on around him, though his prose may have suffered somewhat by their distractions. His biographer, J B Lyons, recounts that, in his late teens, at a concert in the Albert Hall, Siward suddenly became unconscious and convulsed. Epilepsy was diagnosed and an operation was suggested. Only Sir Victor himself was regarded as appropriately competent and it was on him that the awful responsibility fell.

There was sufficient recovery after surgery for Siward to join the army and gain a commission in 1914. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion Artists Rifles attached to the Gordon Highlanders. On the 25th December 1920 he died of wounds received at Neuve Chapelle 1915. The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War. It was a British offensive in the Artois region of France He is buried in Steep [All Saints] Churchyard in Hampshire.

For an account of the second ‘rescue’ we refer to an edition of

The Orkney Herald newspaper, dated May 25th 1880.

SINGULAR LOSS AND RECOVERY OF £83. – On Wednesday last, when the steamer Lizzie Burroughs was leaving the moorings at Sourin, Rousay, Capt. Reid had occasion to lean over the bulwarks, when an envelope containing £83 and some silver coin dropped out of his pocket into the sea. It is customary for the captain of this and other packets to convey large sums of money to town. In the present case the money had been handed to Capt. Reid by Mr. Thomas B. Reid, Clerk to the Rousay School Board, for the purpose of being lodged in one of the banks in town. On falling into the water the envelope floated for a few moments, but sank just as a boat approached. Capt. Reid sent the steamer to town in charge of the mate, and proceeded himself to the Clerk of the School Board, and informed him of the loss, when it was decided to proceed to Kirkwall by a boat and endeavour to secure the services of a diver. Mr Calder, one of the divers who has been engaged at the pier, at once proceeded to Rousay, and descended at the place where the money was lost, the depth of water being about four fathoms. He had only been down a minute or two when he discovered the envelope lying on the bottom. Short as the time was that the money had been in the water, a large shell-fish known as a “buckie” had taken up its abode on the top of the envelope, thus effectually anchoring it to the spot. It is fortunate that there is not any strength of tide at this place. Had the loss occurred where the current is swift the cash would probably never have been seen again.

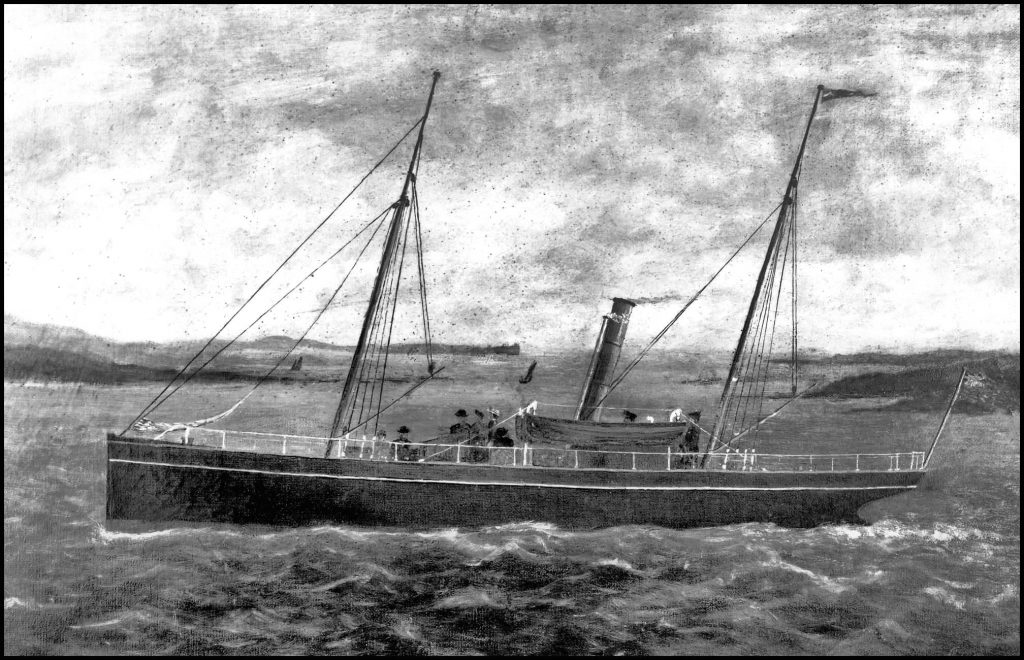

Although steam to the North Isles of Orkney started in 1865 with George Robertson’s Orcadia, certain islands were missed off its roster. Rousay, Egilsay and Wyre are islands situated of Orkney mainland’s North West coast. To remedy the situation Colonel Burroughs formed the Rousay, Evie and Rendall Steam Navigation Company in 1879, 14 years after the Orcadia started. Purpose built for the new company was the Lizzie Burroughs, a wooden steamer built in Leith. She was 61ft long by 15.4’ in the beam. She weighed 31 tons and her engines powered her at 15HP. She served the same route for thirteen years.

The route in 1882 was as follows:

Monday: Sourin (Rousay) – Egilsay – Trumland (Rousay) – Veira (Wyre) – Hullion

(Rousay) – Evie (Mainland Orkney) – Tingwall (Mainland Orkney) – Gairsay

– Rendall Point (Mainland Orkney) – Kirkwall.

Tuesday: Monday in Reverse.

Wednesday: Trumland – Hullion – Aikerness (Mainland Orkney) – Tingwall

– Gairsay – Kirkwall – then return in reverse order.

Thursday: Trumland – Egilsay – Veira – Kirkwall – then return in reverse order.

Saturday: Trumland – Hullion – Aikerness (Mainland Orkney) – Tingwall

– Rendall Point – Kirkwall – then return in reverse order.

There was a distinct lack of piers on this route and many of the Lizzie Burroughs calls were made by waiting offshore whilst small rowing boats or sailing boats came out to meet the little steamer. The ship spent six weeks out of service in 1883 for repairs, then shortly after resuming service was washed onto shore from her overnight anchorage in a heavy storm. She remained on Egilsay for a couple of weeks before being towed to, and beached at Trumland pier on Rousay. Money was raised and the Lizzie Burroughs was moved to Stanger’s yard at Stromness for repairs. After four months out of service she re-commenced trading. Her new timetable had been altered so there were only three return sailings to Kirkwall each week. She continued in this way until 1890 when she went to Aberdeen for a thorough overhaul. In 1892 the Rousay, Evie and Rendall Steam Packet Company Ltd was dissolved and the Lizzie Burroughs was transferred to William Cooper of Kirkwall and renamed Aberdeen.