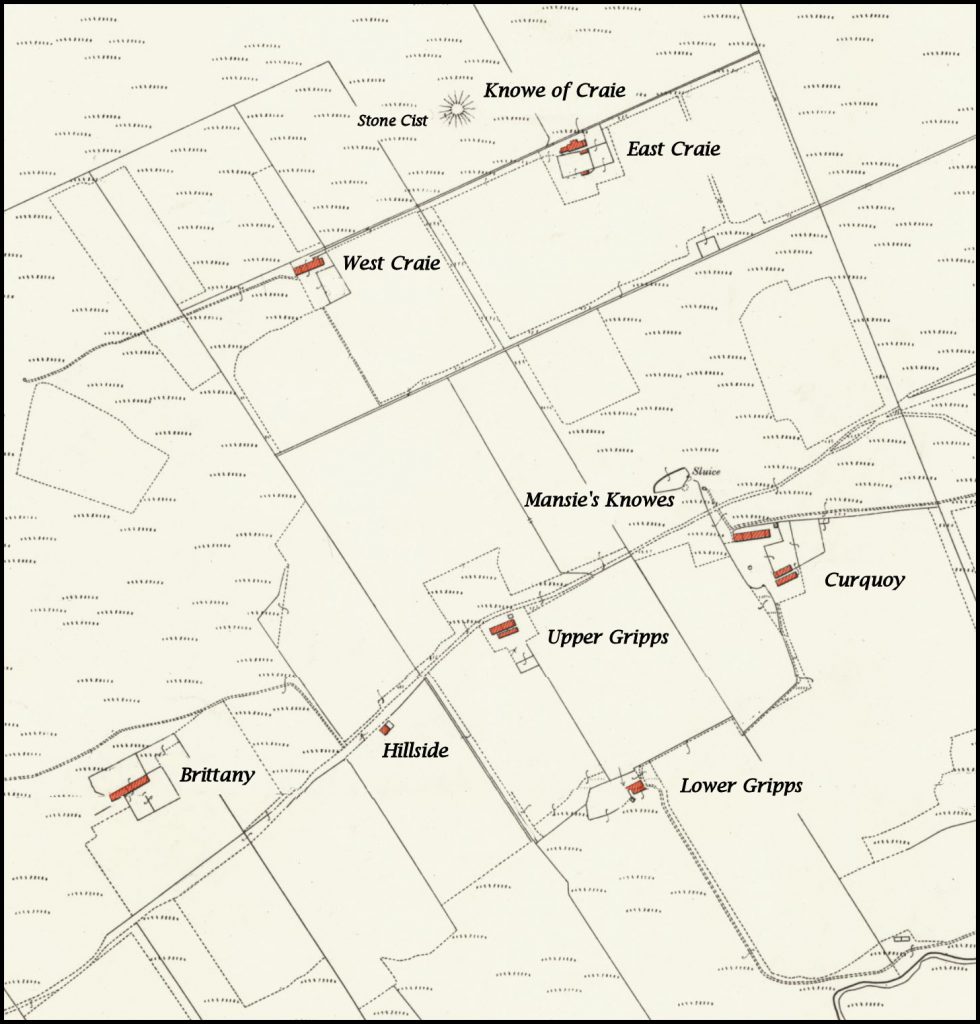

Bittany, Upper & Lower Grips, Hillside, East & West Craie,

& The Knowe of Craie

in relation to today’s farmhouse of Curquoy.

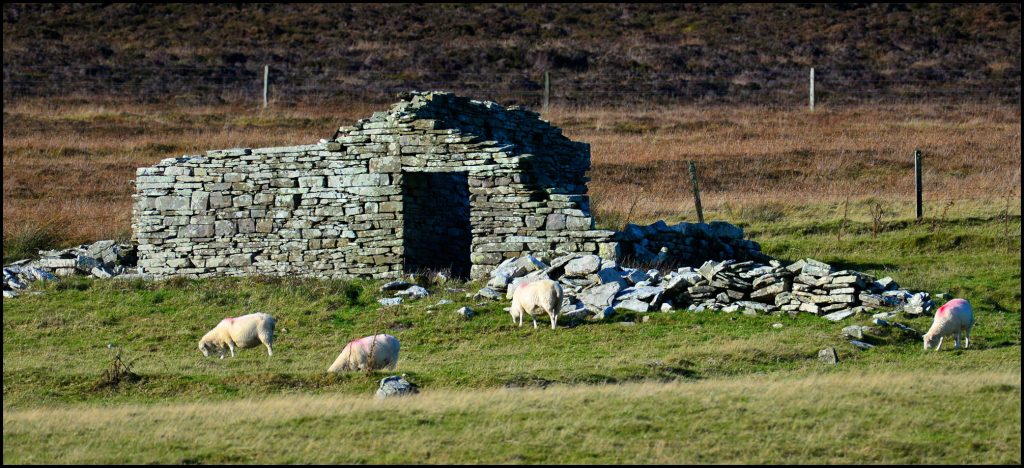

BRITTANY

Brittany was the name of the highest up of all the cottages in the Sourin valley, at the foot of the Brown Hill. Hugh Marwick in his Place-Names of Rousay says it is a fairly certain derivative of the Old Norse word brattr, meaning steep – for the hill rises steeply immediately behind the house. In Norway there was a farm-name Brettene – ‘From the pronunciation this is the def. plur. form of Brett – a bending upwards.’

David Inkster was the first recorded tenant of Brittany, for which he paid an annual rent of £3. In 1871 David lived there with his family and he was farming 43 acres of land in the vicinity. He was born on September 21st 1823, the son of James Inkster and Barbara Mainland of Saviskaill. He earned a living as a boat builder, and he was 26 years old when he married Janet Gibson, the oldest of seven children of Hugh Gibson and Janet Craigie of nearby Skatequoy, who was born on September 26th 1826. David and Janet had three children; Hugh, born on February 27th 1850, Janet Gibson, on Christmas day 1862, and Agnes Davie Gardner, who was born on February 23rd 1868.

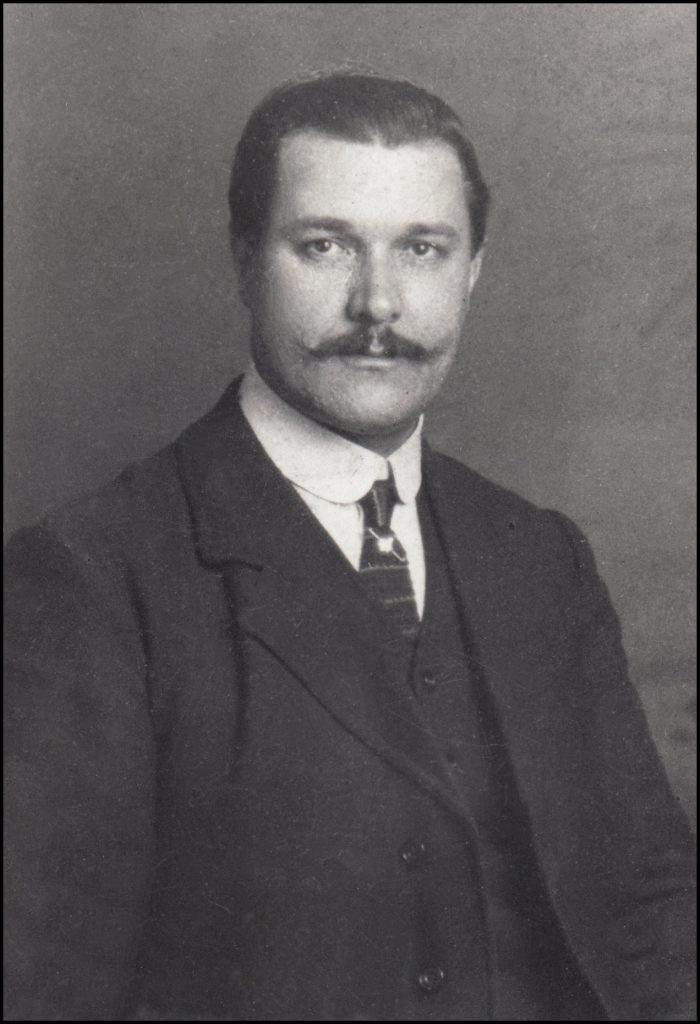

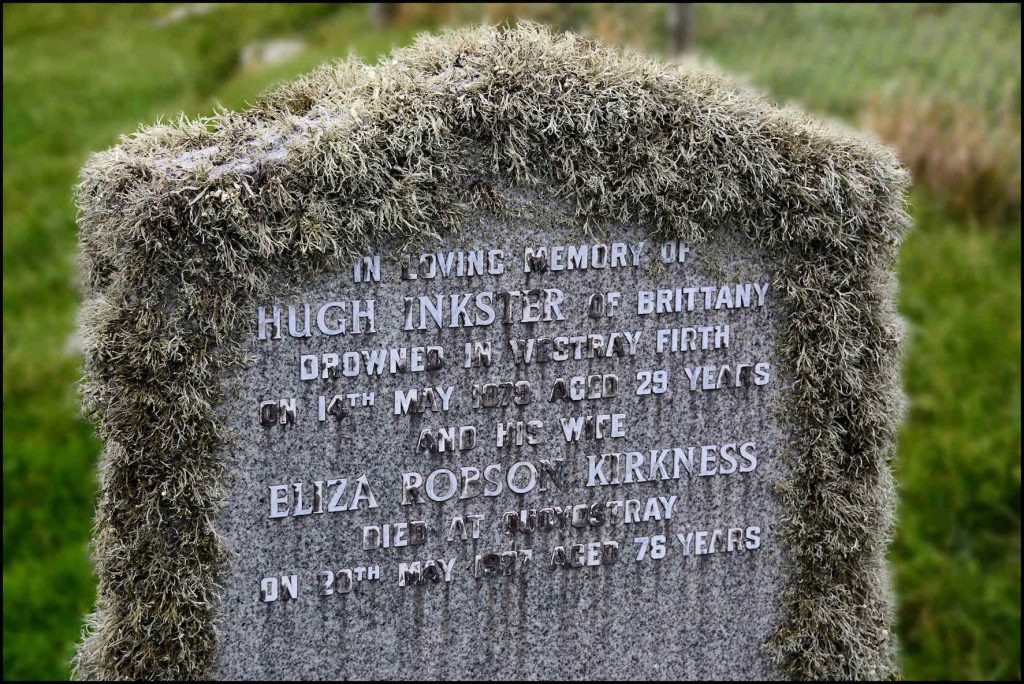

Hugh Inkster [born 1850] married Eliza Robson Kirkness in 1878. She was the daughter of John Kirkness and Mary Alexander, and was born at Quoyostray in 1850. Hugh and Eliza had a son, David James, who was born on 31 December 1878. Tragically, Hugh was drowned while at the fishing in the Westray Firth on May 14th 1879, just a few months after the birth of his son. His body was recovered and later interred in the Wasbister kirkyard. Eliza had a shop at Quoyostray for many years and died in 1927 at the age of 76.

Hugh Inkster’s father David was 55 years of age when he died on the evening of September 12th 1877. He had hepatic disease and had been suffering from chronic bronchitis for seven months. His widow Janet continued living at Brittany with her daughter Agnes, who earned a living as a dressmaker. Janet passed away in 1908, and Agnes moved south to be closer to her sister Janet. Agnes worked as a domestic housekeeper at Linhope, a 22-roomed house in Powburn, Alnwick, Northumberland. She herself passed away on March 8th 1919. Janet married gamekeeper Robert William Reay in January 1899, living at Glendale, Northumberland. She passed away on February 20th 1933.

HILLSIDE

This is the name of a vanished house in Sourin, a little east of Brittany – not a trace of which exists today. In 1861 it was occupied 67-year-old Thomas Louttit and his 59-year-old wife Marian, and they farmed the adjacent 16 acres of land. Previously they had been living and working at the farm of Breckan, Wasbister. With her Christian name variously spelled, ‘Marian’ was christened Mary Ann, and was the daughter of Hugh Gibson, Sketquoy, and Janet Inkster, and she was born on April 14th 1799. She and Thomas ‘were married before witnesses’ on New Year’s Day 1828, according to their marriage certificate. Thomas passed away on July 20th 1865 aged 72 years, and is interred in the Wasbister kirkyard.

In 1871 Cecilia Leonard, a 73-year-old hand loom weaver’s widow, then classed as a pauper, lived at Hillside having moved up the hill from Whiteha’. That hand loom weaver was James Pearson, and they married on December 5th 1845. When James died at the age of 72 in 1860 Cecilia reverted to her maiden name.

GRIPS

Upper and Lower Grips were two small crofts east of Brittany, halfway between there and Curquoy. The Orkney word ‘grip’ signifies a little ditch or watercourse, on the north side of the Sourin Burn, and in a land valuation rental of 1865 the tenant was paying an annual rent of £3 for – Greenrips.

UPPER GRIPS

The census of 1841 tells of Alexander Leonard and his family living at Upper Grips. He was the son of Peter Leonard and Janet Louttit, Cutclaws, Quandale, where he was born on Christmas Day 1808. He was baptised on January 17th in the New Year, his parents surnames being spelled Lennard and Lowtit in the parish record. On January 10th 1832 he married Margaret Grieve. They had four sons: John, born in December 1832; Alexander, in January 1835; James, in November 1836; and Malcolm, who was born on September 15th 1839.

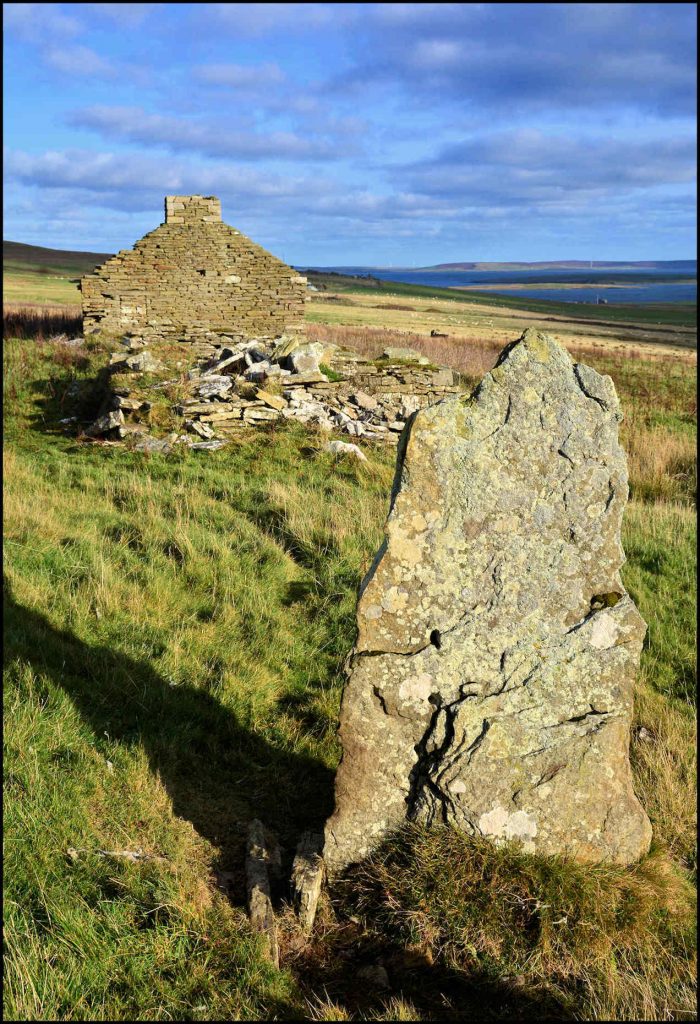

West Craie is just visible above the Curquoy barn.

In 1851 Upper Grips was called Brigs End in the census of that year – but reverted to Upper Grips when the relevant forms were filled out ten years later. By that time Margaret passed away on March 13th 1871, and when the annual population count was carried out a few weeks later on April 3rd, widower Alexander was on record as being a farmer of 14 acres of land.

In 1845 Alexander was paying 10s. a year rent and by 1887 it had risen to £6.0.0. for the 11 acres arable and 2 acres pasture. This was reduced to £4.0.0. by the Crofter’s Commission, and his son Malcolm paid a similar sum when he was tenant.

Malcolm Leonard was married to Mary Craigie, daughter of fisherman James Craigie and his wife Barbara, and she was born when they were living at Quoyfaro. Malcolm was 22 and Mary 23 years of age when they were married in Stromness on January 16th 1862. They had eight children: James, who was born in October 1862; Alexander Robertson, in May 1864; Mary Jean, in November 1866; Margaret Grieve, in November 1868; Malcolm Craigie, in November 1870; Annie Budge, in March 1874; Isabella Drever, in 1878; and John, who was born in 1884.

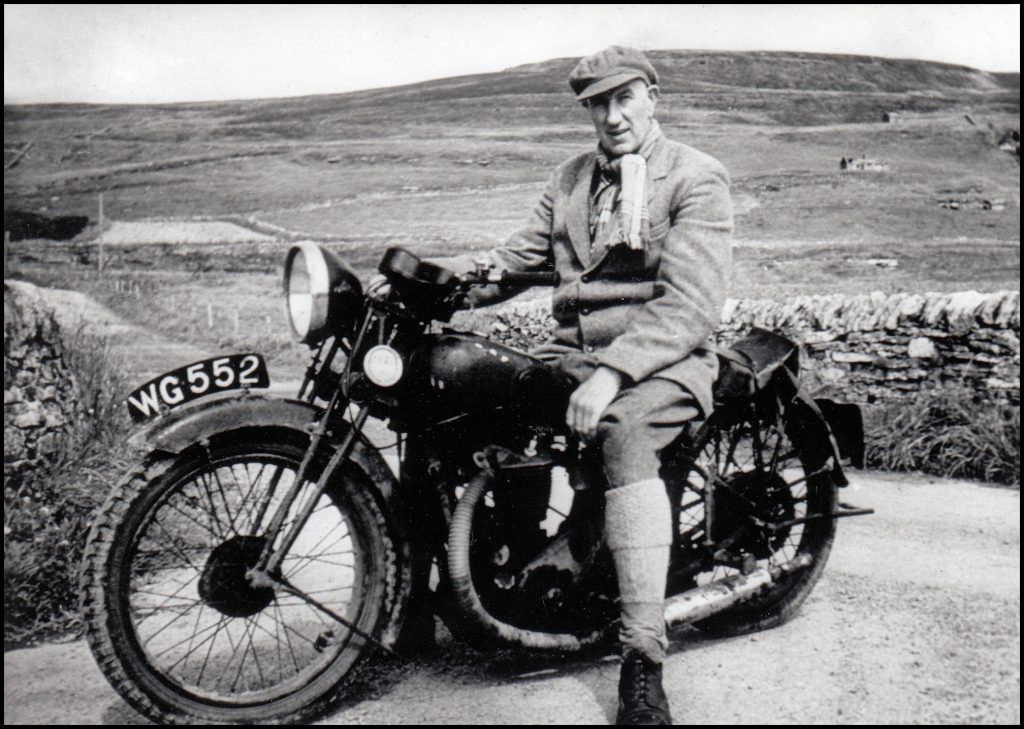

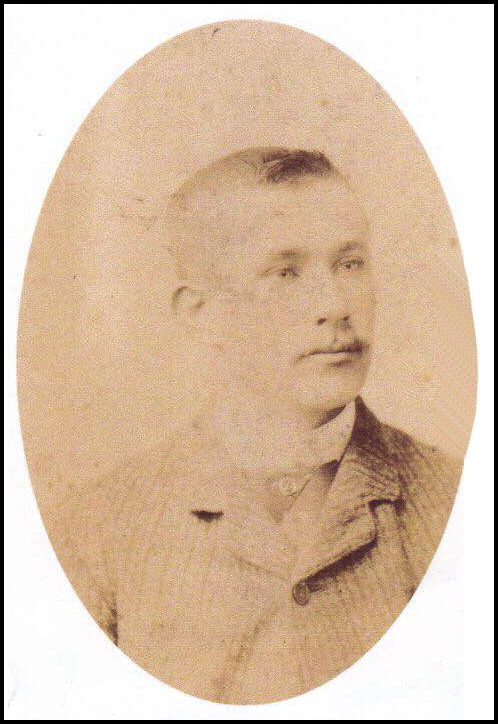

Malcolm Craigie Leonard, born November 1870.

He married Winifred Spence Sutherland,

Uyeasound, Unst, Shetland,

on January 18th 1906.

Thanks to Marion Paterson, Stromness

for the photo of her grandfather.

Malcolm’s father Alexander died on August 4th 1890 at the age of 82. His wife Mary died on June 23rd 1904, and Malcolm moved to Quoys with Isabella and John. Grips was then in the occupation of the Sabiston family, who had moved over to Rousay from Watten, Egilsay. John Sabiston was the son of George Sabiston and Barbara Harrold, and he was born in March 1858. In 1895 he married Margaret Inkster, daughter of James Inkster, Ervadale, and Margaret Pearson, Kirkgate, who was born in October 1861. They had five children: John Donaldson, who was born in 1894; Robert, in 1896; George, in 1898; Mary Ann, in 1899; and James, who was born in 1901.

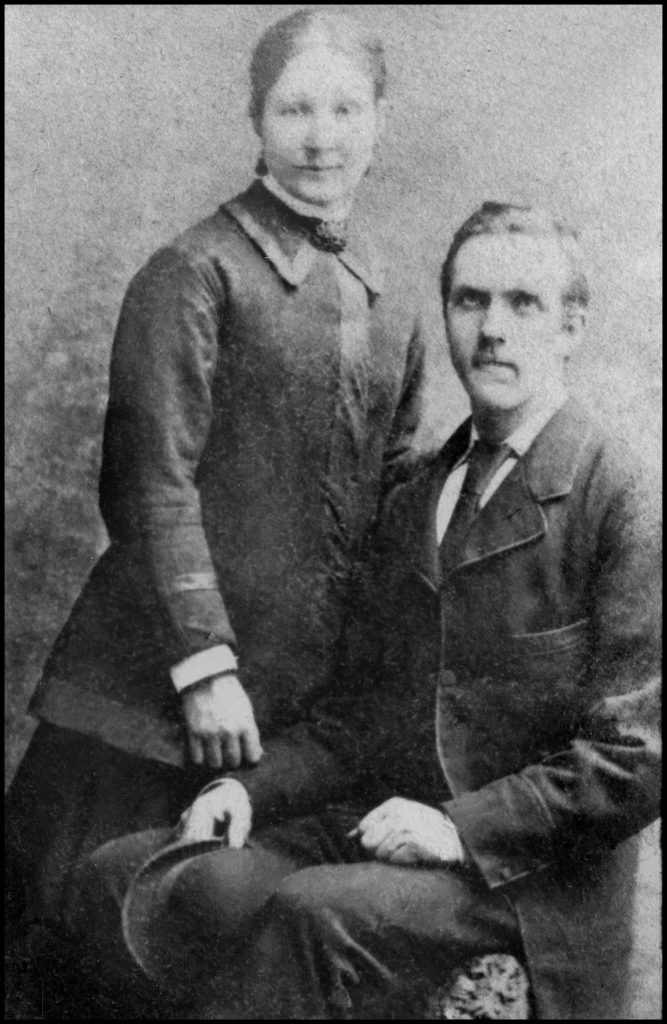

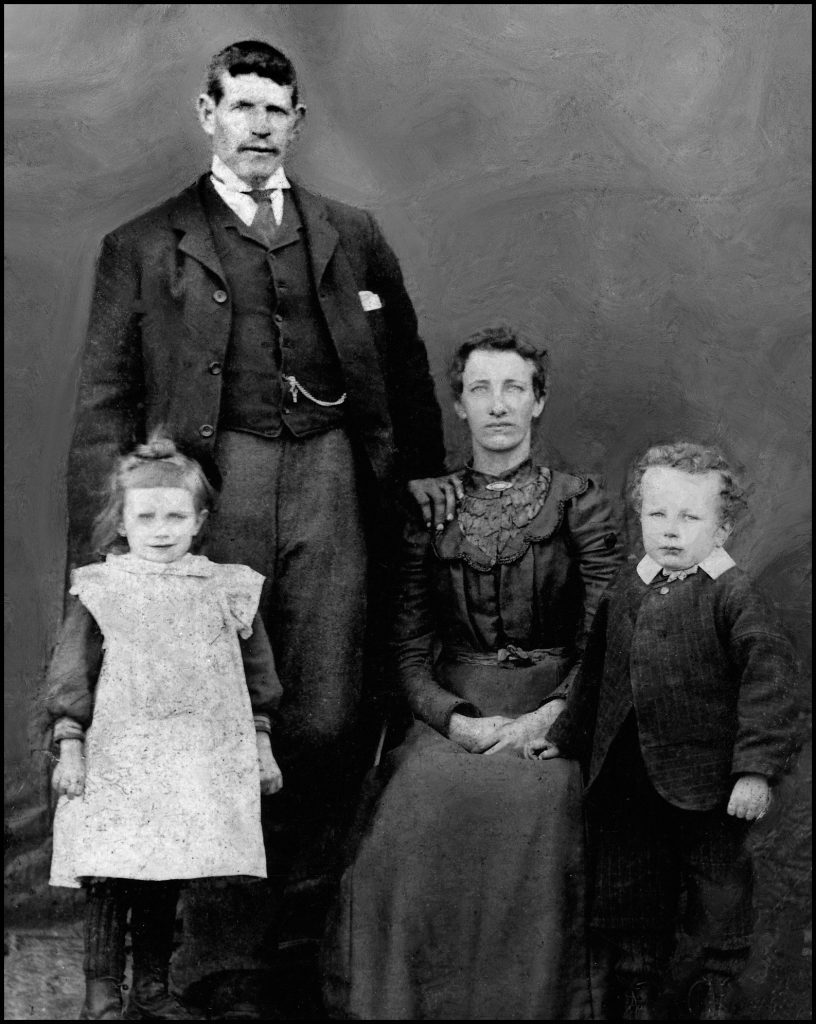

The last occupants of Grips were the Hourie family. Annie Budge Leonard, born in 1874, married David Brown Hourie, Deerness, who was born in April 1866. They wed in 1894 and are pictured on the left with their two children: Mary Ann [Nanny], who was born in 1897 and later married Archer Clouston Snr. Their son Malcolm was born in 1898. In 1925 he married Ellen Mary Craigie, the youngest of the thirteen children of Magnus Craigie and Ellen Cooper, Falquoy, Claybank, and later Pliverha’. Malcolm, or ‘Mackie’ as he was known, was gamekeeper for the Trumland Estate.

LOWER GRIPS

Lower Grips was called Greenrips in a land valuation rental of 1865. It cost James Craigie £1.5.0. to rent in 1845. James was the son of John Craigie and Margaret Murray of Bergodel, later known as Guidal, and he was born c.1773. On December 19th 1809 he married 26-year-old Janet Grieve, and they raised a family of seven children: Janet was born in October 1810; Barbara, in August 1812; James, in August 1814; Margaret, in August 1816; Jane, in August 1823; John, in February 1826; and William, who was born in June 1828.

Janet was 75 when she passed away in 1858. Her husband James was 88 when he died just three years later. Son John took over the tenancy of Lower Grips, paying and annual rent of £3.0.0., rising to £4.0.0. by 1887 for the 6 acres arable and 3 acres of pasture land.

John, born in 1826, was 37 years of age when he married Mary Wood Marwick, daughter of James Marwick and Christian Groundwater of Millhouse, close to Woo, and she was born on May 4th 1831. They raised a family of six: Mary Christina was born in May 1865; John Marwick, in November 1866; Jessie Ann Muir, in September 1868; Maggie, in March 1872; Jemima, in July 1876; and James, who was born in July 1878.

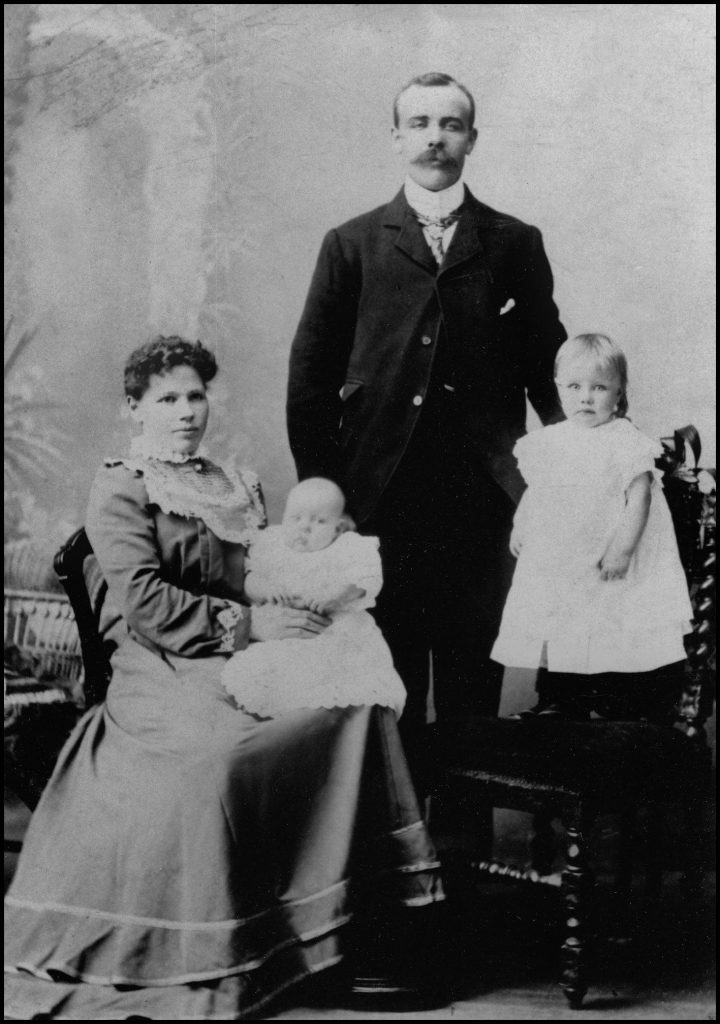

Jessie Ann Craigie [born 1868] was 23 years of age when she married 21-year-old Herbert John Sandbach, son of tailor John Sandbach and Sarah Ann Cadman. The ceremony took place at Milliken, Kilbarchan, Renfrew, on December 1st 1891. Jessie Ann was working in Kilbarchan as a domestic servant and Herbert was a groom. They are pictured above with two of their three children: John, born in 1893; and Herbert, in 1896. Their third, Mary Ann Jessie, was born in 1898.

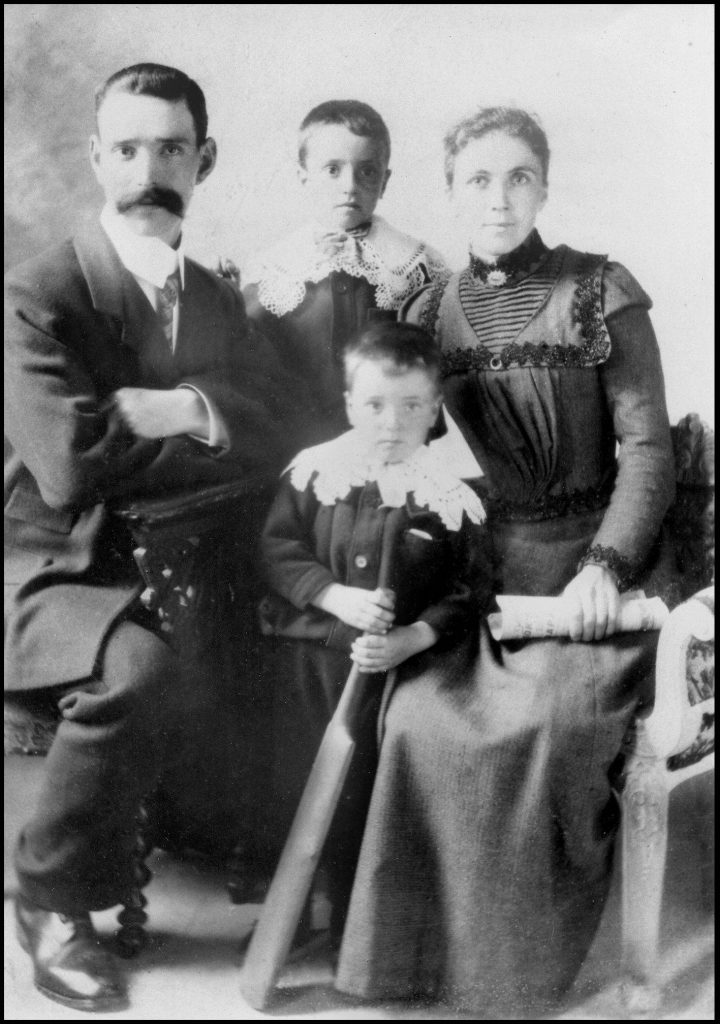

Jessie’s sister Maggie Craigie [born 1872], was also 23 years of age when she married 23-year-old police constable George Hackston at Linwood, Renfrew, on October 9th 1895. George was the son of miner David Hackston and Mary McConnell. They are pictured with their two sons George, born in 1897, and David Craigie, who was born in 1899. They also had a daughter Maggie Craigie, who was born in 1904.

In 1888 the Crofter’s Commission reduced John’s rent to £3. He died in 1892, and that same year his widow Jane renounced the croft and moved to Windbreck on the Westside. Two years later widower James Cooper took over the tenancy of Lower Grips, having moved the short distance from Standpretty with his daughter Mary. James later moved to Sandwick, and Lower Grips was then unoccupied.

CRAIE

East Craie and West Craie were two small crofts, situated in the face of the hill above Curquoy in Sourin. There are numerous spellings, but I will go with Craie for that was provided by the man who built them, William Robertson, to the Ordnance Survey when Rousay was ‘mapped’ in 1879-80. Hugh Marwick in his Place-Names of Rousay thought this an interesting but obscure name, and though he suggested an origin its authority was to be regarded as ‘no more than tentative’!

The record of a legal process dated 1823 is preserved in Kirkwall Sheriff Court Records Room in which John Gibson of Broland, Rousay, was prosecuted for slander by Janet McKinley, wife of John Pearson of Cruehannie. He was alleged to have called her ‘a thievish limmer’, and this he did ‘the day of the last sheep-shearing at Craya.’ This happened in the days when the hill was public common, and when the sheep of the whole district grazed on it. Mrs. Pearson must thus have been so insulted on the public sheep-shearing day when all the sheep were rounded up and confined in enclosures at Creya for shearing or ‘roo-ing.’

The name is also found in several other Orkney districts, e.g. Evie, Deerness, Orphir, and Stromness parish, and the situation of each is such that it might well have been that of the local shearing pens. The common Orkney word krue, an enclosure or pen, which occurs frequently in place-names (usually in the form kru), e.g. Cruar, Crooannie, Steincroonie (all in Sourin), and which is a Norse loan-word from the Old Celtic cró, a pen for sheep, cannot be the source of Creya. But there is another Old Norse word krá, a corner, which is sometimes confused with the preceding term. Subsequent investigation into similar Norse and Faeroese language revealed the word krogv, translated as meaning a corner or nook, a place for storing odds and ends, e.g. peats. Faeroese place-names include Kú-krogv, ‘cow-krogv’, and Seyõa-krogv, ‘sheep-krogv’, which prove that the term has been used there for enclosures for cattle and sheep. It may be suggested therefore that in the Orkney name Creya we may see a specialised use of this term for the kind of pens into which sheep were driven for shearing. Hugh Marwick says that what he wrote above was written while he was under the impression that there was no local memory of a sheep-shearing site at Creya. He subsequently met by accident the then present tenant who informed him he had been told by an old neighbour long dead (Malcolm Leonard) that a part of the farm now cultivated and known as The Hole o’ Creya was the place where sheep were shorn in olden days.

By 1861 stonemason William Robertson was living at Crey, as it was called in the census, a house he built with his own hands – having been evicted from the Westside. More on that in a minute or two. William was the son of Alexander Robertson and Margaret Irvine of Egilsay, and was born on January 3rd 1810. In 1844 he married Elizabeth Harcus, the daughter of William Harcus and Christy Flaws, and they had four children; twins John and William born on November 16th 1846; Alexander, born on April 23rd 1849; and James, on May 10th 1851. William and his family moved here from the Brinian, and paid 12s. rent in 1867.

In 1871 William and Betsy Robertson were living at East Crey, while William Craigie and his wife had moved into West Crey, a house situated nearby with 20 acres of land. William Craigie was the son of William Craigie and Mary McKinlay, Feelie-Ha’, and he was born c.1814. His wife was Mary Kirkness, the daughter of John Kirkness and Barbara Craigie, who was born in November 1824 when they lived at Quoyostray. William paid £3.11.0 rent in 1869, rising to £4.0.0. in 1887 for the 10 acres arable and 10 acres pasture. This was reduced to £3.10.0. by the Crofter’s Commission in 1888.

During the Napier Commission investigation in Kirkwall on July 23rd 1883, the Chairman interrogated Rousay Free Church minister, the Rev. Archibald MacCallum who had been elected to stand as a delegate for the island’s crofters. He read a statement to the Commission explaining the crofters’ grievances regarding the present laird Frederick William Traill-Burroughs. At one point he touched on the eviction of certain tenants, one of whom was William Robertson, though it was noted that these evictions actually took place in the time of the previous laird George William Traill.

The Chairman, Lord Napier, said:- The subsequent evictions you referred to are the cases of the tenant of Hammer and the occupiers of East Craye?

The Rev. MacCallum replied: Yes.

How many evictions were there?

East Craye was occupied by one crofter. He was evicted from one place which he had built and reclaimed, and then he was allowed to build in East Craye. The rent was then 10s., which has increased until it is now five times that amount.

How long was he in the place before the rent was raised in that way?

We have a statement from him here – [reads]

‘Statement by William Robertson, crofter, of East Craye, Sourin, Rousay, for Her Majesty’s Royal Commission on the Highlands and Islands:

My croft of East Craye is on the property of General Burroughs of Rousay and Viera. I am a native of the parish of Rousay, and am now seventy-two years of age. About 1845, I took a small croft at another part of the island from that where I now live, and got on that croft about a quarter of an acre cultivated when I entered on it. I paid 22s. of rent on that holding. As I improved, more rent was put upon me, until at last I was obliged to leave it altogether. I then got permission to build a dwelling on the hillside where I now live, where there was no cultivation of any kind, nor houses. I began to build, and got up with much trouble a humble cottage and outhouses suitable. I ditched and drained more than I was able, and got a little of the heather surface broken up. At this time I paid 12s.; but again, as I improved, more and more rent was laid on till I am now rented at a sum which is five times the rent I paid at first for a house I built myself. At the same time the common was taken away from me, as from all others; so that I am now not able to pay such a rent, nor to defend myself in any way, as I am wholly under the control and will of the proprietor.

WILLIAM ROBERTSON. JAMES LEONARD, witness.’

The Chairman asked: Whom was the statement drawn up by?

It was taken from his own mouth by James Robertson [his son] in his own language, and it is signed by himself.

William Robertson did not attend the session, perhaps deciding it prudent to stay away. Which was just as well, as another delegate, James Grieve was asked one question – did he agree with the statements made by MacCallum and James Leonard? Grieve replied in just two words – “I do” – and they were sufficient to result in his later eviction as sub-tenant of Triblo by General Burroughs.

Over the years at East Craie William and Betsy Robertson’s rent increased, but this was reduced to £2.0.0. in 1888 by the Crofter’s Commission. It was at this time that he renounced this croft and moved down the hill to Hanover. East Craie’s next tenant was David Gibson and his family. David was the son of John Gibson, Broland, later Knarston, and his second wife Janet Craigie, and he was born in October 1849. In 1880 he married Ann Gibson, daughter of Thomas Gibson, Broland, and Jane Grieve, Outerdykes, and she was one of twins born in December 1843. They had a son, John, born in January 1880, but he died when he was just two years of age. They had a daughter Ann, born in February 1881, who was an invalid. They had one more daughter, Jane, in 1889, but tragically she died at birth.

William Craigie died in 1895, and the next tenants of West Craie were James Dishan, who was born in Evie & Rendall in September 1847, and his wife Christina, who was born in Westray c.1848. James Donaldson Dishan was the son of James Dishan and May Rendall who, as a young man, was employed as a seaman in the merchant service. He was 28 years of age when he married domestic servant Christina Scollay, daughter of farmer Robert Scollay and Anne Kent. Though christened Christina, she was called Cirsten on the wedding certificate, and the ceremony took place at St Catherine’s Place, Kirkwall, where James was resident at the time. They came to Rousay, and settled at West Craie, but then moved down to Trumland where James was employed as a ploughman, living in a small cottage between the farm’s archway and the road, and it was known to one and all as – ‘Dishans.’

It was a surprise in my research then to find that James Donaldson Dishan had died – at Post Office Cottage, Eday, at noon on May 2nd 1910. The death certificate declared he was a ‘pauper, formerly a farm servant, married to Christina Scolley’, and that he had been suffering from bronchitis and emphysema for five years. The Rousay census for 1911 shows his wife Christina living at Gue, above Westness, and described as a 67-year-old ploughman’s widow.

The same census has no mention of West Craie – but East Craie was then home to James William Shearer and his wife Elizabeth. James was the son of Thomas Shearer and Mary Skea, and he was born at Carrick, Eday, on September 13th 1875. Prior to moving to Sourin James was employed as a ploughman and was living at ‘Trumland cottage’. Circa 1896 he married Elizabeth Wylie, daughter of fisherman Peter Wylie and Mary Laird, Hunda, Burray, who was born on August 15th 1864. Elizabeth was 77 years of age when she passed away at East Craie on the morning of August 13th 1942. James William died from heart problems at 5 Bridge Street, Kirkwall, on October 13th 1948 when he was 72 years old.

KNOWE OF CRAIE

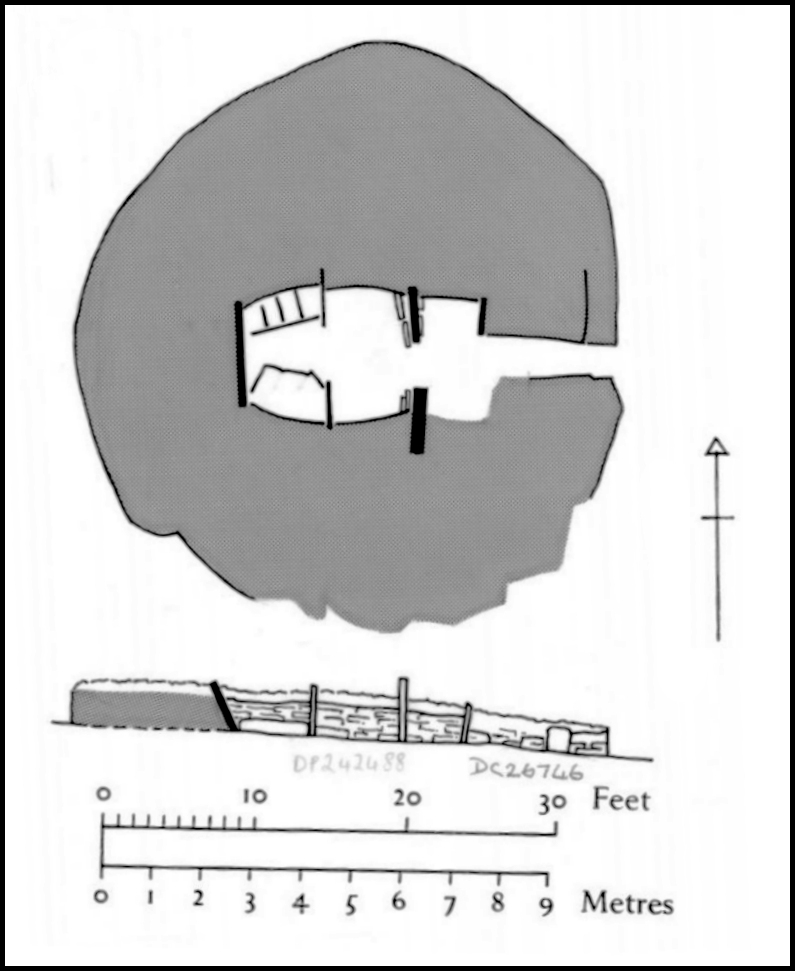

The Knowe of Craie stands in enclosed land just above the vanished farmstead of East Craie, which itself in just above Curquoy in the Sourin valley. It was excavated by Walter G. Grant, and various pottery sherds, two scrapers, and four flint chips from the site are in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, presented by Grant in 1944-45.

The monument is a burial cairn of Orkney-Cromarty type, dating from the Neolithic period (probably in the fourth millennium BC). It survives as a circular grass-covered mound, approximately 12m in overall diameter and stands up to 0.8m high. The cairn was partly excavated in 1941, which has revealed the internal structure. A passageway, 2.8m long by 0.7m wide, enters the cairn from the E. It leads to a burial chamber, 4.6m long by 2.7m wide, which is divided by two pairs of slabs into three compartments. There had been benches on each side of the chamber, but these are no longer visible.

There seem to have been two floor levels: an upper one of clay (at least in the innermost compartment), below which a layer of ‘dark ashes’ was spread over the whole chamber. Finds included the remains of several pots (including an unusual bowl likely to be early in the Orcadian pottery sequence), flint scrapers and chips, and human remains. Outside the cairn, on the N side of the entrance, a small hollow in the rock contained ashes, burnt bone fragments, flint chips and pottery sherds. The cairn is situated on a gentle South-facing slope at approximately 110m above sea level, overlooking Egilsay and the Westray Firth.

[Text source: Historic Environment Scotland]

[Diagram: AS Henshall – Canmore collection / 1540665]

MANSIE’S MOUNDS

DISCOVERY OF AN URN OF STEATITE IN R0USAY

NOTICE OF THE DISCOVERY OF AN URN OF STEATITE IN ONE OF FIVE

TUMULI EXCAVATED AT CORQUOY, IN THE ISLAND OF ROUSAY,

ORKNEY. – BY MR GEORGE M. M’CRIE, CORQUOY.

The cluster of mounds explored is situated a few yards to the north west of the farm house of Corquoy, and are locally known as “Manzie’s” (or Magnus’s) mounds. They have always been considered as burial-places. The measurement of the largest mound (in which the urn was found) was about 50 feet in circumference, and the top 5½ feet above the surrounding level, but there is no doubt it stood much higher within living memory. The others are smaller. A trench was dug from the north into the centre of the largest mound.

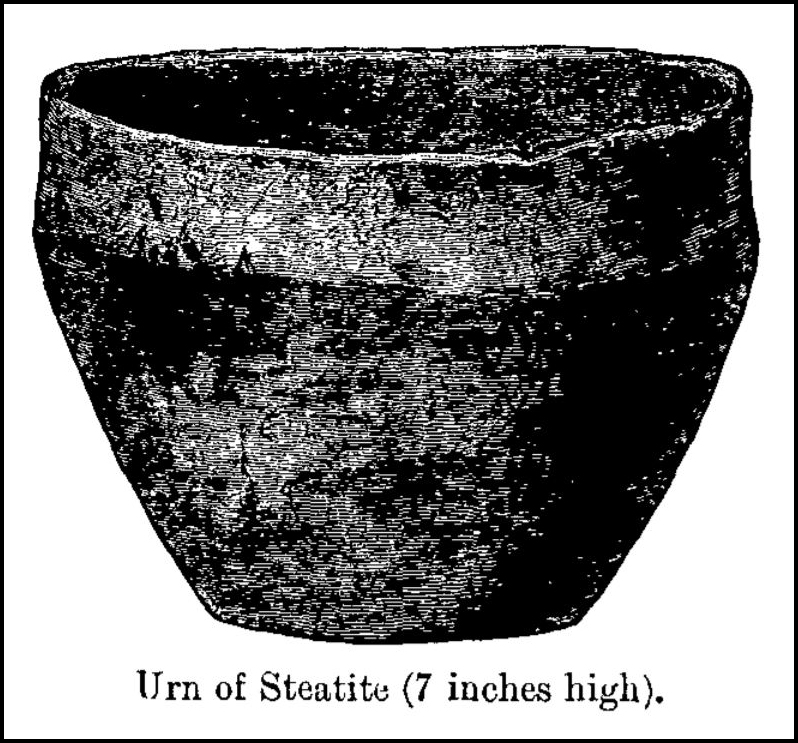

A cist was found almost in the centre of this mound, and at about the level of the surrounding ground. It consisted of a top and bottom stone (flat slabs partly naturally plane at the edges, and partly chipped into form), with four side stones, the whole neatly pieced and cemented with tempered red clay, probably from the Sourin burn some little distance off. The stone is of a hard blue nature, unlike any in the immediate neighbourhood, but like some to be found on the shores of the island. The cist was oblong in form, placed lengthways to N. and S., and measured inside about 2½ feet by 2 feet by 1½ depth. It was almost wholly filled with clay, ashes, and very minute fragments of bones, which crumbled to the touch. Marks of fire were visible on the stones, and fragments of what seemed to have been peat were among the contents. In the centre of the cavity of the cist was the urn. It stood mouth upwards, and was completely filled with clay, bone fragments, &c., of the same kind as outside. The material of the vessel is steatite, heavy and hard, but full of cracks, and rather brittle in parts. It measures 9¾ and 8 inches across the mouth, and stands 7 inches high; the thickness irregular, but averaging ¼ inch; weight about 3 Ibs. About one-third of the base was wanting when found, and a small portion of one of the sides has given way, but the piece can be accurately fitted in, being preserved.

The remaining mounds contained stone cists similar to the foregoing. Two of them were almost square in shape, and the smallest of all measured only 12 inches by 6 inches, and was without the clay cement. No urns were found or remains of any kind, except comminuted bones, and the smallness of the fragments of bone prevented anything being ascertained regarding their character. One small piece of what is apparently a frontal bone has been preserved.

It may be mentioned that in several of the mounds the side stones were buttressed by irregular blocks, more firmly to support the weight of the earth above.

[Mr Anderson stated that this appeared to have been a small cemetery of those peculiarly interesting interments which in his paper on the “Relics of the Viking Period in Scotland” he had correlated with a special class of interments in Norway of the later Iron Age. They are interments after cremation, and they differ from Celtic interments in having the burnt bones deposited in an urn of stone instead of the large ornate vessel of baked clay which is the invariable rule in Scotland. These stone urns, both in Norway and in this country, are usually of steatite. Some are of large size, one now in the museum being 20 inches high and 22½ in diameter. They often bear the marks of the chisel or knife with which they have been scooped out, but occasionally, as in the case of this one from Rousay, they have been smoothed and polished. The isles of Orkney and Shetland (which, as is well known, were colonised by the Norwegians in the later period of their Paganism) are the only localities on this side of the North Sea in which this class of burial has yet been found. They are therefore but little known, and up to this time no relics of distinctive character have been found with them except the urns. It is unfortunate that we have no detailed accounts of the phenomena of the burials, most of which have been investigated more with reference to the objects they have contained than to the phenomena they may have presented. In all probability the examination of these mounds during their excavation by some one who knew the differences between the phenomena of Celtic and Scandinavian burials might have detected evidence not obvious to the unskilled eye, and thus settled the question].

[Extracted from The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, January 10, 1881. pp 71/72. Available at Orkney Library & Archive.]

[All black & white photos courtesy of the Tommy Gibson Collection]

[Edited map section courtesy of National Library of Scotland – Map Images maps.nls.uk/index.html]