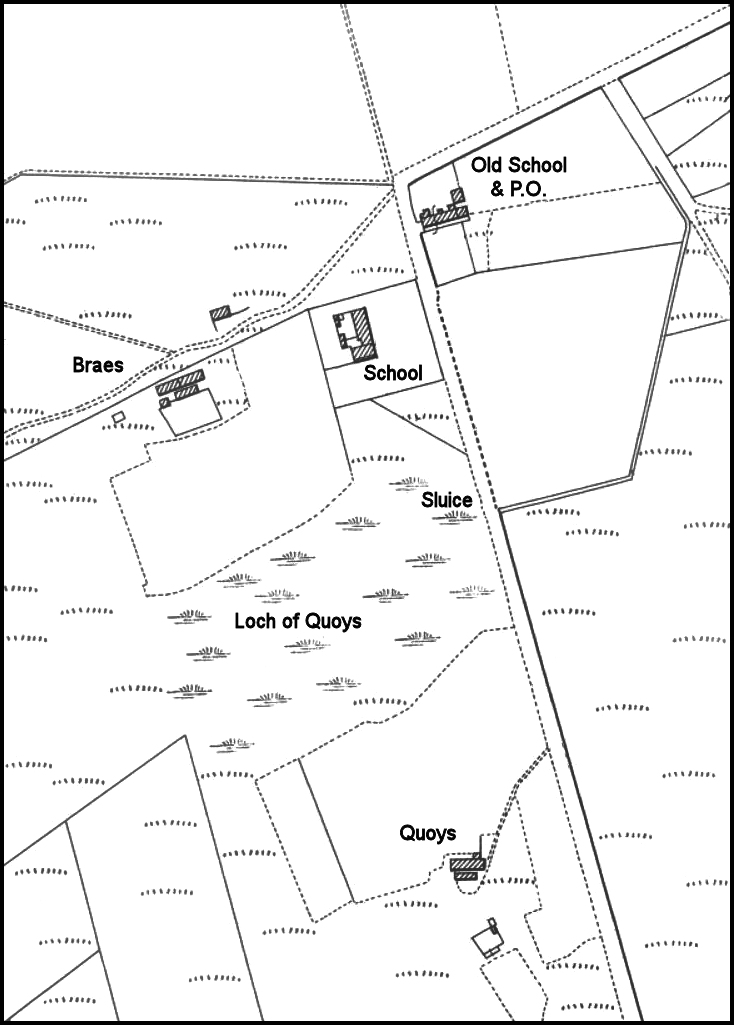

Quoys, the old Sourin croft on the southern margin of the Loch of Quoys, is a good example to illustrate how it is thought that typical ‘quoy’ farms arose. The Old Norse word kví was used for a fold for animals, and such folds were often situated at places where animals gathered together to spend the night. A natural place for cattle pasturing outside the tunship or farm dykes was some sheltered spot along the outside of the dyke. In the course of time such a spot would become so highly fertilised by the constant animal manuring that it would become well worth cultivating. Hence, a ‘quoy’ farm would be established there, and the old dyke shifted back to enclose it, or a new dyke might be built, of stone and turf, around itself.

Such is the explanation of the fact that quoy-farms, as a general rule, are to be found on the outskirts of the older settlements, more or less on the line of the old tunship dykes. In the case of Quoys at Sourin, the old hill-dyke is still clearly visible inside the park of Banks, just across the public road from Quoys.

In 1845 fisherman Hugh Cooper and his wife Jane lived at Quoys. The rent at this time was £1.2.0.

By 1861 Quoys was occupied by farmer William Inkster who was a widower. He was married to Margaret Gibson, but she died in 1855 aged 60. William, the son of William Inkster and Robina Rendall was born in 1795. He and Margaret had seven children: Bethynia, who was born in April 1823; Christian, in August 1825; Ann, in August 1827; William, in October 1829; Margaret, in April 1832; James, in March 1836; and Hugh, who was born in February 1839. At the time of the census in 1861 the three eldest daughters, all unmarried, lived with William at Quoys. Bethynia, though called Robina in the census return, was a 39-year-old agricultural labourer; Christie, 37, was a seamstress; and 35-year-old Ann was a domestic servant. William died in 1869, at the age of 74.

In 1871 Christie was head of the household and described in the census as a pauper, while her older sister, Robina, was employed as a labourer. Their younger brother James, a fisherman, was a joint tenant, and he lived there with his wife Margaret Pearson. She was the daughter of James Pearson and Mary Leonard of Kirkgate and was born in 1837. They had six children: Margaret, who was born in 1861; James, born in 1865; William, in 1867; Hugh, in 1869; David, in 1876; and Robert, who was born in 1880. The oldest daughter, Margaret married John Sabiston, the son of George Sabiston and Barbara Harrold of Whitemeadows.

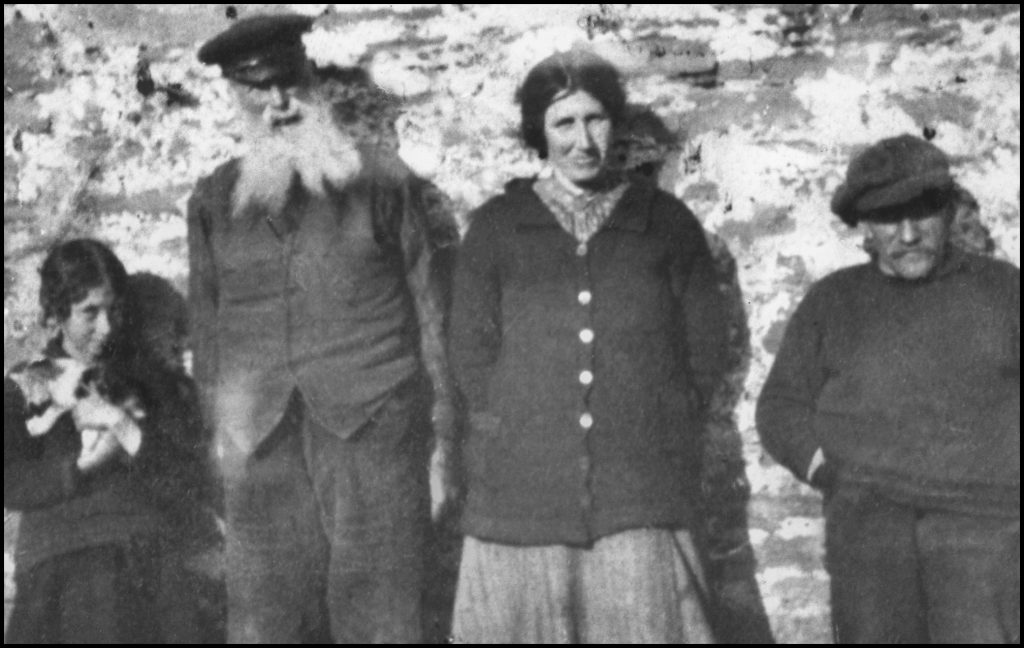

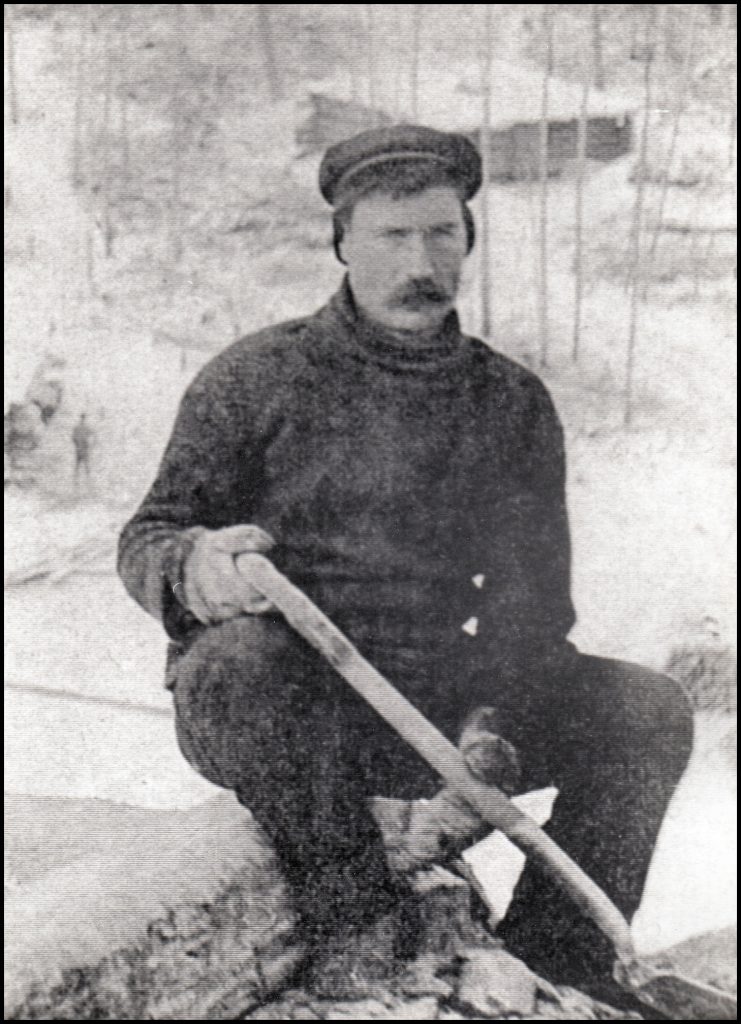

To the left is David Pearson Inkster, Ervadale, later Quoys, Sourin. born 1876. A blacksmith who went to America, his father was a brother of Hugh Inkster, Shetland & Westness.

Come the time of the 1911 census, carried out on April 5th, Quoys was occupied by 71-year-old Malcolm Leonard. He was the youngest of the four sons of Alexander Leonard and Margaret Grieve of Upper Grips, Sourin. Born in April 1840 he married Mary Craigie in 1862, daughter of James and Barbara Craigie, who was born in January 1839 at Quoyfaro. They had eight children: James, who was born in 1862; Alexander, born in 1864; Mary Jean, in 1866; Margaret, in 1868; Malcolm, in 1870; Annie, in 1874; Bella, in 1878; and John, who was born in 1884.

Back to Quoys and the 1911 census. Living with Malcolm were his 33-year-old daughter Bella, a former domestic servant, son John, a 27-year-old agricultural worker, and three grandchildren: Mary Ann Hourie, a 13-year-old scholar, was Annie’s daughter, having married David Hourie of Deerness; Charles Flett, 9, who was also at school, and Mary Ann Leonard, who was just five months old, both of whom were Bella’s daughters.

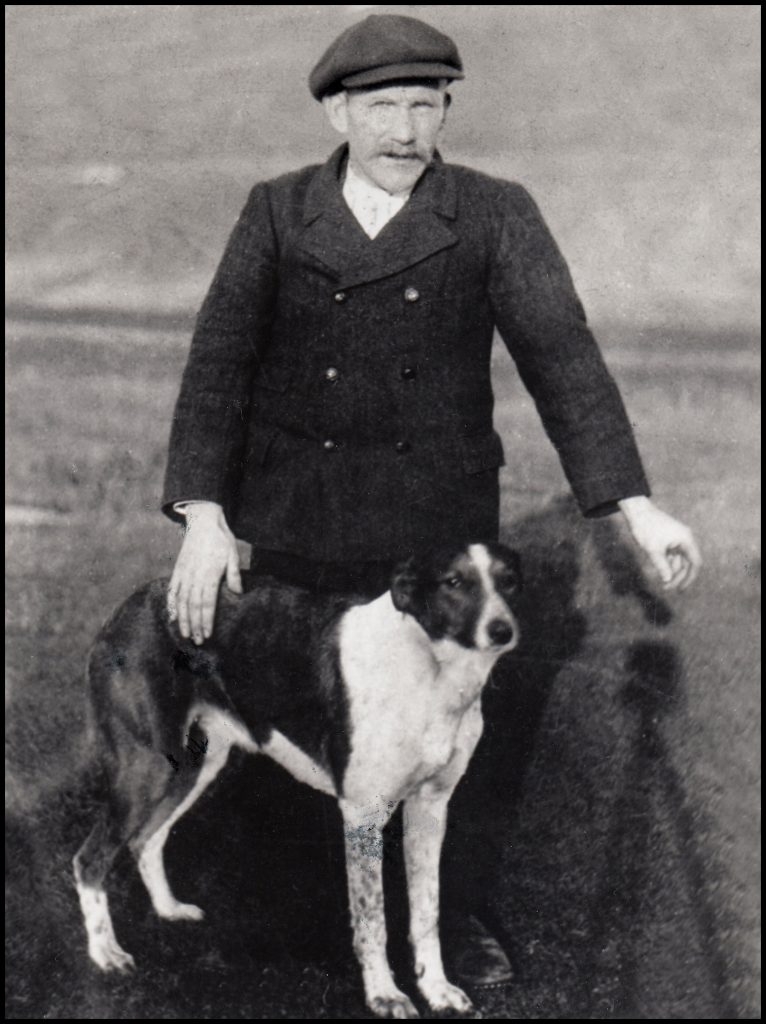

A nice photo of John Leonard and his faithful hound.

[See the shadow of the tripod-mounted camera]

Braes, close to the school in Sourin, and also known as Barebraes in the past, housed three families in 1851. Christie Craigie, a widowed 62-year-old pauper, lived at Barebraes 1 with three of her unmarried children; Janet, a 34-year-old seamstress; 31-year-old Barbara who was a knitter; and 26-year-old James, who earned a living as a farmer/fisherman. Christie’s husband was Magnus Craigie of House-finzie [Finyo], Sourin, who died in 1840 at the age of 54. Christie and he raised a family of ten children between 1811 and 1832

Barebraes 2 was occupied by James Grieve, a 90-year-old pauper from Egilsay, his wife Barbara, who was 70 years old, and their 53-year-old unmarried daughter Barbara, who, like her mother, was a hemp spinner.

Rebecca Yorston, another pauper, lived at Barebraes 3. She was the 70-year-old widow of Peter Yorston of Oldman, Sourin, and was supported by her 27-year-old daughter Ann, who earned money by plaiting straw. Rebecca, born in 1783, was the daughter of Mitchell Craigie of Holland, Frotoft, later Hullion, and Ann Mainland

In 1861s Braes 1 was occupied by Barbara Work, a 77-year-old widow and pauper. Living with her was Margaret Grieve, her unmarried step-daughter, 64, also a pauper, and Nanny Work, Barbara’s unmarried sister, 69, who earned a living as an agricultural labourer.

Christy Craigie was still living at Braes with her seamstress daughter Janet – together with son James and his new wife Betsy Mowat. She was the daughter of John Mowat, Scowan, and Isobel Yorston, Trumland, and she was born in April 1827. [Scowan was a small croft below Midgar].

Rebekah [Craigie] Yorston and Christie Craigie both died at Braes in 1872. The death certificates of both ladies record their parent’s names as Mitchell Craigie and Rebekah Marwick. Robert C. Marwick in his book Rousay Roots wonders if Mitchell was married twice, with Rebecca and Christian being children of the earlier marriage.

James and Betsy Craigie continued to live at and work the land at Braes into the early 1900s. James died in 1910 at the age of 85, and Betsy passed away two years later in her 82nd year.

Thomas Meil Shearer was the son of James Shearer [1836-1897] and Margaret Meil [1835-1896], and he was born at Freehall, Stronsay on June 4th 1873. He was employed as a ploughman, living at Housebay, when he married 25-year-old Margaret Jane Miller on February 24th 1898. She was the daughter of Robert Miller and Elizabeth Shearer, and lived at Hunton on the island,. They had four children: Tomima, Anna, Ruby, and Ronald – all born in Shetland, where Tom was employed as a carter, living at South Houlland, Tingwall. Eventually the family moved back to Orkney, Tom farming the land at Lochend, just east of The Ouse and Leira Water, Shapinsay. His wife Margaret passed away at 6pm on October 21st 1940 – after which Tom and his unmarried daughter Anna moved to Rousay, living at Braes.

OLD SCHOOL

In 1721 a petition was sent to the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge from the Presbytery of the North Isles pleading Rousay’s case for a school. ‘The case of the island of Rousay is very lamentable, having no School-master, and the people for the most part both Ignorant and Barbarous, and the Presbytery entreats that a Charity school be settled there.’

Two years later a school was promised to the island which in turn promised that accommodation and a stack of peats would be provided for the schoolmaster. It was, however, to be another two years before the school was established on a small area of ground at Banks in Sourin and it opened for the first time in 1725.

The North Isles Presbytery was asked to find a suitable person to take charge of the school in Sourin, and in due course the Rousay minister, the Reverend Andrew Graham, reported that a David Marwick who had been doing some private teaching on the island was such a person. The Presbytery examined Marwick and found that he had ‘sufficient knowledge of the principles of our holy Religion for that station and could read and write very well and had also competent knowledge in Arithmetick.’ Having been tried and tested and found fit for his duties David Marwick became Rousay’s first official schoolmaster. He was to remain in that post for the next 49 years.

By 1827 an Assembly school had been established in the premises which had been provided for the SSPCK school a century earlier. The curriculum in Assembly schools was fairly basic, consisting of reading, writing and arithmetic, and of course, religious instruction. Girls were given instruction in sewing and knitting.

The school’s teacher, when the census was carried out in 1841, was forty-year-old William Smeaton and he lived at the schoolhouse with his wife Harriet, also 40 years of age, and their seven children: Harriet, 14, William, 12, Mary, 10, Thomas, 8, John, 6, Elizabeth, 4, and one-year-old James. Smeaton remained in the post till 1843. It was in that year that a great many ministers and members of their congregations left the Church of Scotland and formed the Free Church. This breakaway was known as the Disruption and was brought about mainly through dissatisfaction with the practice of patronage, whereby the patron in a parish, usually the largest landowner, had the right to select the parish minister. Smeaton ‘came out’ at the Disruption and joined the Free Kirk, as did a lot of other Assembly and Society teachers. Consequently many of them, including Mr Smeaton, were dismissed from their posts.

He was replaced by Thomas Balfour Reid, the son of George C. Reid and Elizabeth Yorston of Shoreside [the original name of what we know today as Balfour village], Shapinsay, and he was born on January 5th 1824. At the time of the 1851 census he was 27 years of age, and living in the schoolhouse with his wife Betsy Thomson, 32, from South Ronaldsay, and children Thomas, 5, and William, who was two years old. Living with them was Betsy’s unmarried sister Helen, who was a 30-year-old seamstress. Things were not all plain sailing for Thomas though, for he was not without his critics in Sourin. In September 1851 the Assembly’s Education Committee decided to dismiss him after receiving an unfavourable report from the parish minister. Later, the committee had a change of mind and decided to retain him until the Secretary could visit Rousay and judge the situation for himself. Reid escaped dismissal at that time and continued to serve in Sourin until the School Board took over more than twenty years later.

Important changes in Scottish education were brought about by the Education (Scotland) Act of 1873, which decreed that responsibility for providing and administering schools would lie with publicly elected School Boards. Another of its main provisions was that attendance at school would be compulsory for all children between the ages of 5 and 13 years of age.

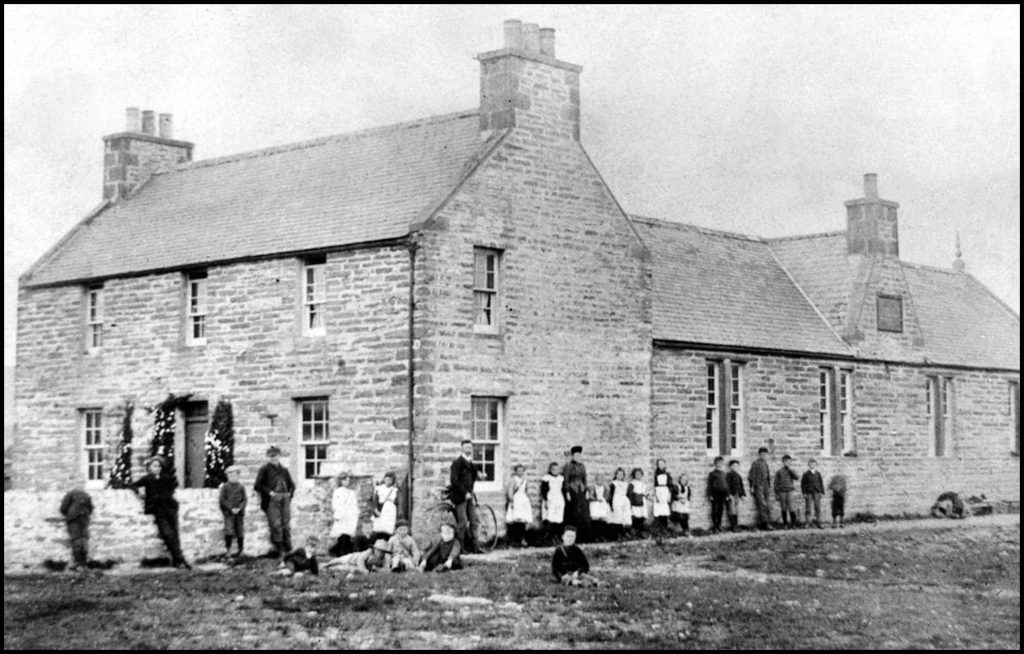

At this time a petition signed by the heads of 42 families and ten others in Sourin was presented to the new Rousay School Board asking for a new school building and a ‘thoroughly qualified teacher.’ The widespread dissatisfaction with Mr Reid was reflected in the poor attendance with only one child in four attending school. The Board agreed to the points raised in the petition, and within a few months permission was obtained from the Education Department in Edinburgh to build a new school on the opposite side of the road from the old one. Two years elapsed before building began, but eventually the new school, pictured above, was officially opened by General Burroughs in January 1876. Mr James Inkster was now the schoolmaster, a position he held until 1881.

The following story involving Thomas Reid was printed in the Orkney Herald on May 25th 1880:-

SINGULAR LOSS AND RECOVERY OF £83. – On Wednesday last, when the steamer Lizzie Burroughs was leaving the moorings at Sourin, Rousay, Capt. Reid had occasion to lean over the bulwarks, when an envelope containing £83 and some silver coin dropped out of his pocket into the sea. It is customary for the captain of this and other packets to convey large sums of money to town. In the present case the money had been handed to Capt. Reid by Mr. Thomas B. Reid, Clerk to the Rousay School Board, for the purpose of being lodged in one of the banks in town. On falling into the water the envelope floated for a few moments, but sank just as a boat approached. Capt. Reid sent the steamer to town in charge of the mate, and proceeded himself to the Clerk of the School Board, and informed him of the loss, when it was decided to proceed to Kirkwall by a boat and endeavour to secure the services of a diver. Mr Calder, one of the divers who has been engaged at the pier, at once proceeded to Rousay, and descended at the place where the money was lost, the depth of water being about four fathoms. He had only been down a minute or two when he discovered the envelope lying on the bottom. Short as the time was that the money had been in the water, a large shell-fish known as a “buckie” had taken up its abode on the top of the envelope, thus effectually anchoring it to the spot. It is fortunate that there is not any strength of tide at this place. Had the loss occurred where the current is swift the cash would probably never have been seen again.

——————–

In the 1880’s Thomas Reid was still head of the household at the Old School, but he had retired from teaching. In 1881 he was 56 years of age and he was an Inspector of the Poor, the island’s Registrar, and Clerk to the Rousay School Board. His wife Betsy was then in her 62nd year. They had a boarder at that time, Duncan McFadyen, a 34-year-old schoolteacher, who was born in Islay.

Ten years later the Sourin schoolhouse was occupied by a new teacher, 29-year-old William Simpson from Banff, his wife Maggie, and baby son William. The Old School had new occupants too – the Munro family who had moved from Trumland Lodge. Head of the household was Alexander Munro, a 49-year-old merchant from Bower, Caithness. He was the son of Angus Munro and Janet McDonald, and was born in April 1841. On July 14th 1876 he married 26-year-old Christina Steven, daughter of Alexander Steven and Janet Calder. They had eight children: Malcomina Calder, who was born in 1878; Agnes MacDonald, born in 1880; George Morrison, in 1883; Alexander James, born in 1885; Hugh, in 1887; David William, in 1888; Mary Ann McKay, in 1890; and Albert Edward, who was born in 1893.

Over the years Sourin school had a succession of teachers: John Moyes in 1881; Alexander Oswald in 1886; William Wilson in 1887; William Simpson in 1890; Alexander McPherson in 1894; David Clouston in 1895; John Carrill in 1896; Louis McLeod in 1900; and Jessie Marwick, daughter of Hugh and Lydia Marwick of Guidall, who was head teacher from 1903 to 1911 at which time Lydia Gibson Baikie took over. She was the daughter of Kirkwall baker James Baikie and Lydia Gibson Craigie of Myres.

Old School in 1911 housed the Sourin post office, with Alexander Munro being employed as Sub Post Master. When the census was carried out on April 5th that year Alexander and his wife Christina had been married for 34 years, 8 months, and 8 days. With them that night were four of their offspring: Agnes, 30, employed as a cook, but home on a visit; sons Hugh, 24, and Albert, 18, both employed as farm horsemen; and Mary Ann, who was a 21-year-old general domestic servant.

Reference, with permission to reproduce, was made to Robert Craigie Marwick’s book From My Rousay Schoolbag for the detailed information regarding schooling, teaching, and the building of the new Sourin school earlier in the text.

[All photographs, unless otherwise stated, are from the Tommy Gibson Collection.]