A Fowling Excursion to Rousay in 1864

From the The Orkney Herald, Tuesday October 4

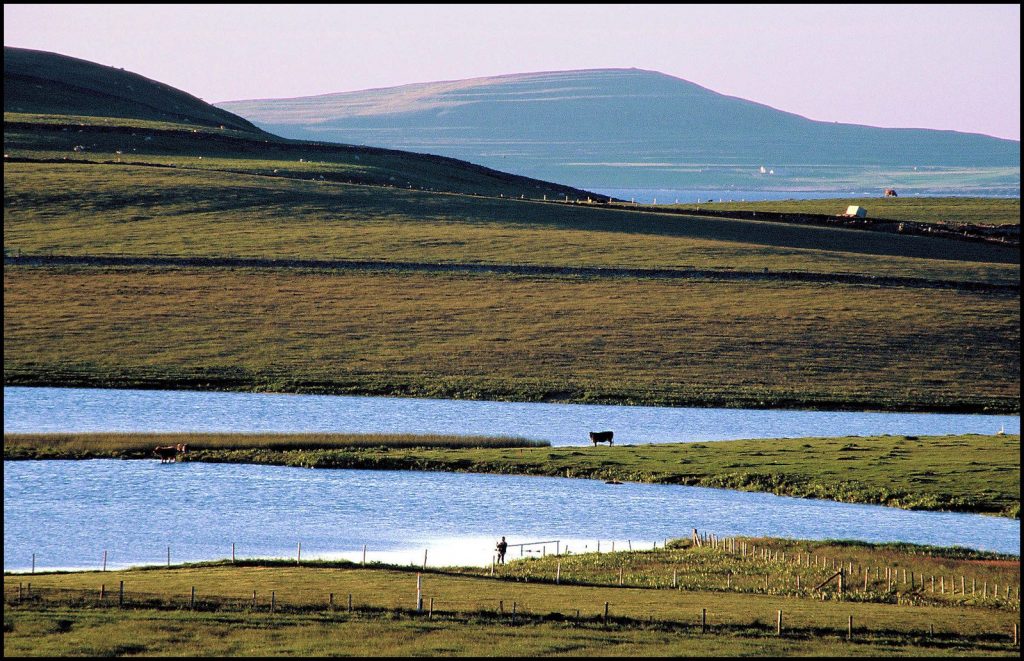

A FOWLING EXCURSION TO ROUSAY. – Rousay is the Hoy of the North Isles, rearing his steep ridges proudly above the waters, and presenting attractions in the way of wild scenery and commanding views of sea and shore, which cannot fail to be appreciated by every genuine lover of the picturesque. Hills, whether bright with fields of grass and grain, or brown with heath, or grey with weathered stones, excite within the heart an unquenchable longing to scale their sides and surmount their summits, and more especially is this the case when the hills, far-seen over leagues of blue water, swell skyward from some island shore. Rising suddenly and abruptly from the sea level, island hills have a more imposing and attractive aspect than continental ridges of greater altitude. The Ward Hill of Hoy, for example is little more than fifteen hundred feet high, and yet, proudly beetling over the billows of the Atlantic, he may cope in grandeur with the Alps of Glencoe. Although the Rousay hills are not as weird, lofty, and precipitous as the heights of Hoy, they possess a lonely majesty of their own as they roll up from the shore, ridge after ridge, and sublimity clothes their grey summits when the storm-cloud from the Atlantic sweeps over them with streaming skirts. The lower reaches of the range smile with the verdure of cultured lands, and thus, from the fine combinations of the beautiful and sublime in scenery. Rousay may safely be pronounced the most picturesque island to the north of Pomona.

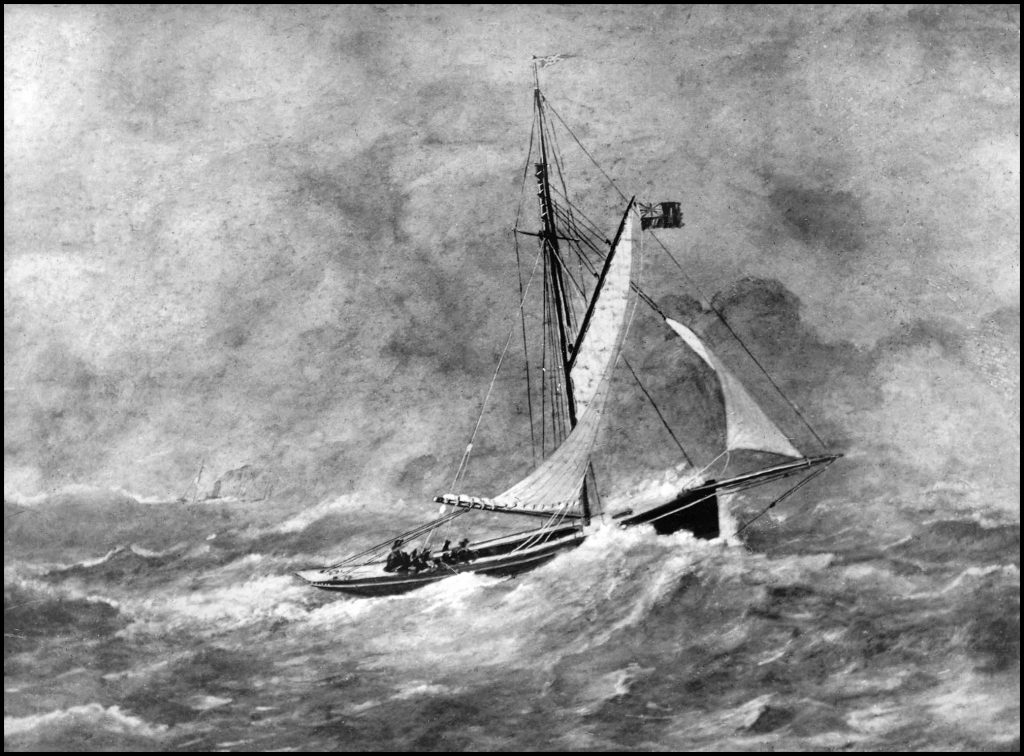

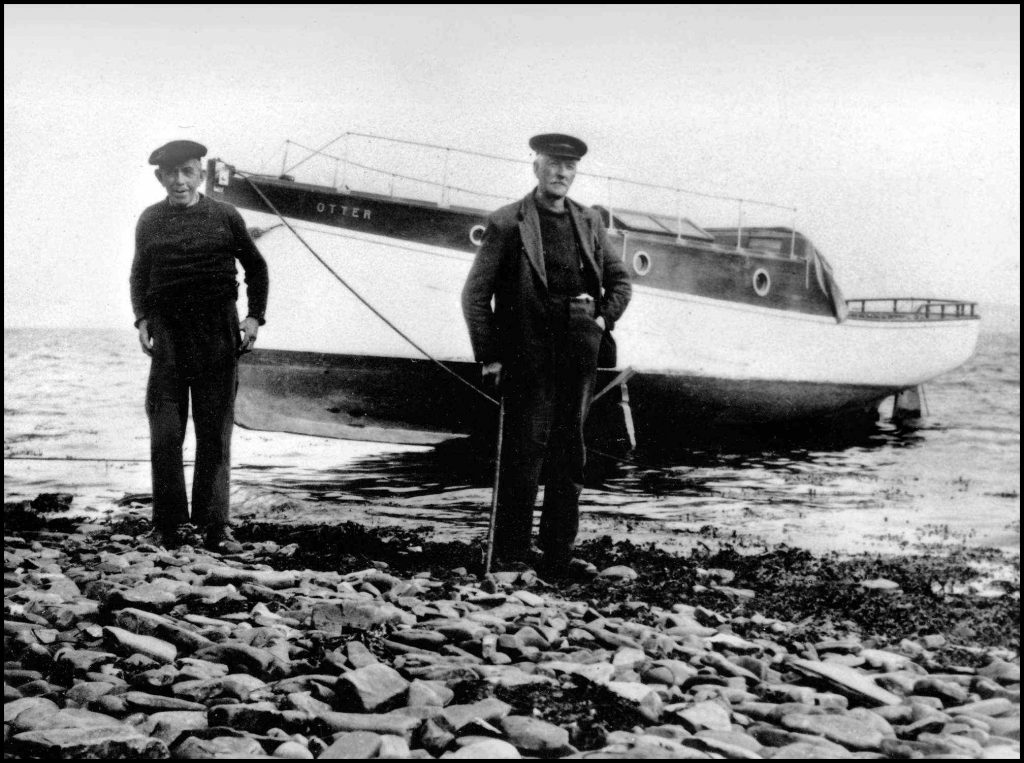

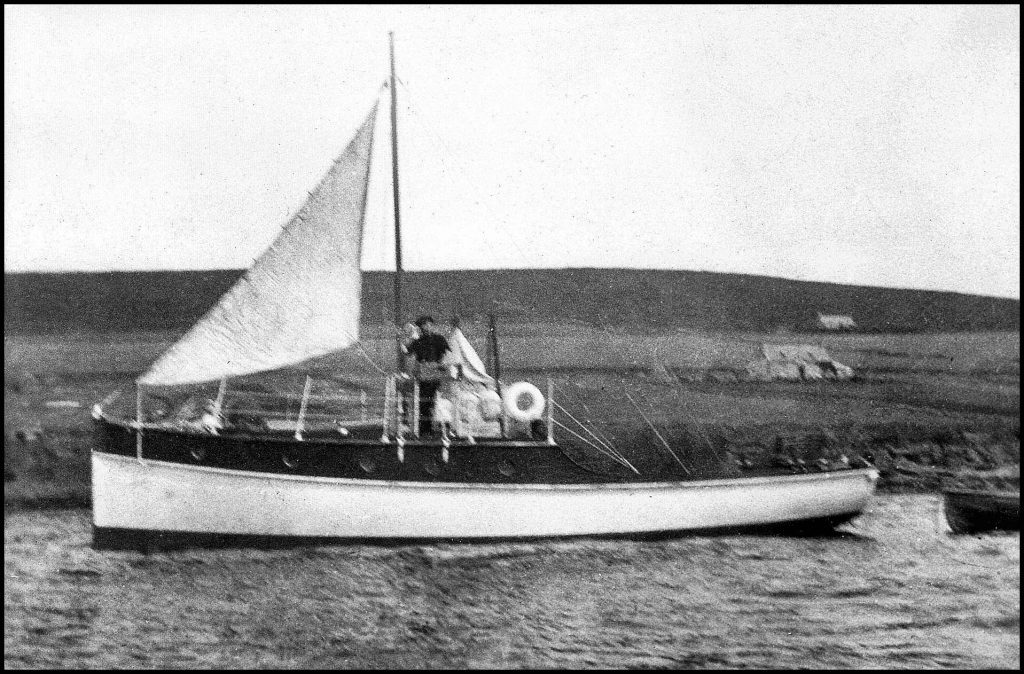

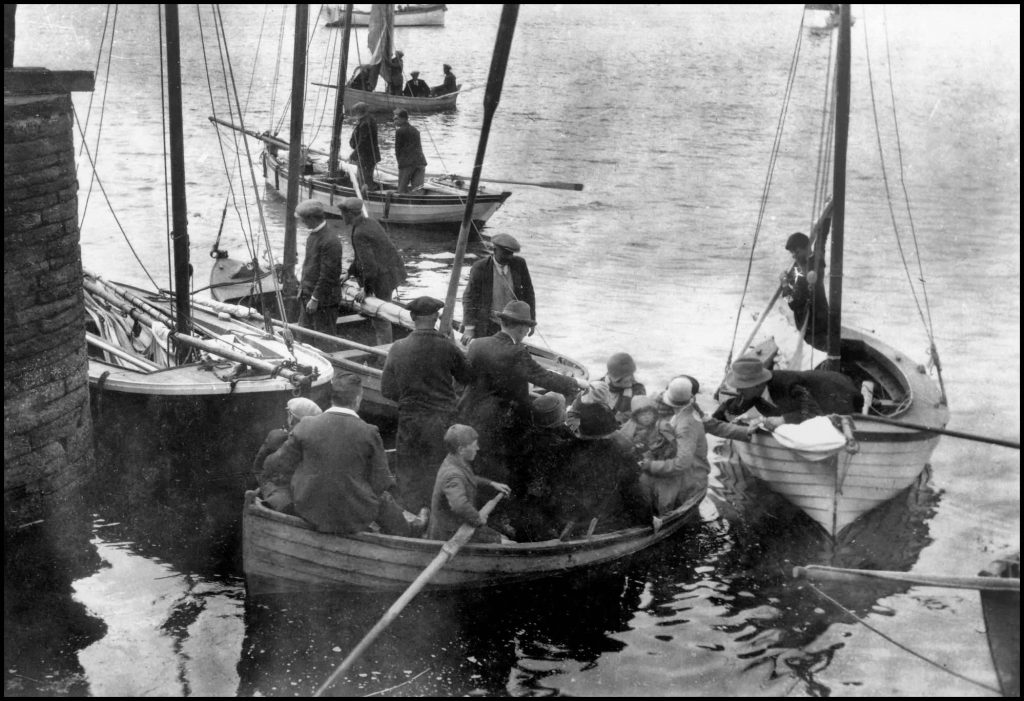

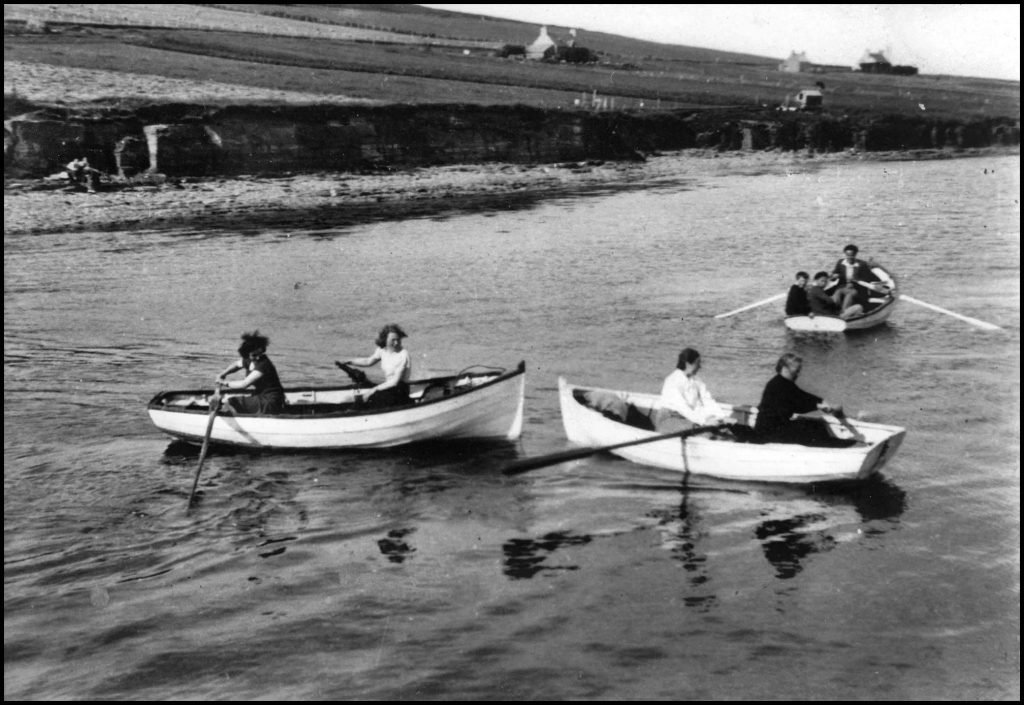

To this romantic hilly isle, towering above its neighbours, like Saul among the Princes, let readers now accompany me in fancy upon a fowling and exploring expedition; and our Aldershott friend, who enjoys a fireside trip, will not, we trust, forget to shoulder his imaginary musket and blaze away at any visionary auks and guillemots. It is a sunny morning (10 o’clock A.M.) almost the beginning of autumn, when our yellow-painted pleasure boat, the property of a courteous and accommodating citizen of Kirkwall, glides peacefully off from the vicinity of the harbour under mainsail and jib, which forms an easy-going rig for amateur boatmen to handle. Our crew, including the sagacious skipper and the whole company, consists of six hands, so that the boat is not overburdened, and there will be room for working the oars in a calm or for enjoying a noontide lounge when the breeze winnows the waters. Fowling-pieces, rifles, and a carbine belonging to one of the members of the 1st O.A.V. bask harmlessly in the sunshine across the seats fore and aft. The gleam of these well-polished and serviceable weapons gives a somewhat piratical or marauding aspect to our otherwise innocent craft, and the gulls, winging lazily overhead, return upon their course as if to satisfy the suspicion excited by the first glance. The motions of these birds are so graceful, whether wavering high above the mast on wide-spread wings or riding on the swell of the sea, that it seems almost a criminal action to dye their native element with their blood in the wantonness of sport. However, the weapons of destruction in our boat are as yet idle all, and it will be time enough to moralise when the first murder of scarf or gull has been committed. The second or third tack brings us close under the lee of one of Her Majesty’s ships that has taken up her station for a time in the bay, and then we run alongside the Westray packet to hail a friend who is bent on a kelp expedition among the North Isles. He is drawing what consolation he can from a well-used pipe, as the breeze has shed off in the direction of Weyland, and the packet seems unable to pass the floating target of the Kirkwall Artillery Corps. The fate of the packet is also our own, but the oars are swinging out, and we soon make cheery way, welcoming every waft of wind that comes from land or sea. The breeze freshens as we cross the mouth of the fine Bay of Firth, and anon, by the aid of sail and oar, we are coasting along the green shores of Rendall with the grey island of Gairsay in front, and the hills of Rousay shining in the sunshine on the opposite side of the Sound. The waters move around us in soft, silent, glassy undulations, flashing in the sunshine, and flickering in surf on the neighbouring shore. It is a day of pastime for all manner of sea-birds, and now that we are slipping quietly into lonelier waters, bevies of tiesties are seen disporting themselves in front and rear, while a lazy scarff raises himself up at full length over the surface here and there, and shakes his wings by way of apology for missing his fish. The temptation is too strong to be resisted, and though our rigorous rowers have unsteadied their hands by grasping the oar, the weapons of war are eagerly clutched amid a scene that looks the very image and perfection of peace. Powder flasks pass from hand to hand, and the dire clink of the ramrod is heard from stem and stern. Bang goes Number One, and the report echoes over the waters as if the shot were

This was absolutely a rifle shot, aimed at an audacious scarf which, stretching itself above the water, and thus forming a capital target, had the good fortune to escape unhurt as the bullet spluttered into the sea ten paces beyond the living mark. Had the bird been struck by a rifle ball at the distance of fifty yards, he would, without fail, have been cruelly beheaded unawares. Down dives the alarmed but fortunate fisher into the emerald depths of the sea, disappearing so suddenly that he seems never to have existed, and he will give the boat a wide berth ere he again shows his bill above the surface. Bang! Bang! Bang! – double-barrel and single blazing off simultaneously, and a shower of duck-shot scatters the plumage of a happy family if tiesties, dipping and diving on the gladsome waters. Some of them have disappeared, two make short, desperate efforts to escape, fluttering “half on foot, half flying” over the rippling crest of the waves, and a third floats on his back, with his red-webb feet quivering pathetically in the death struggle. Another well-aimed shot reduces the two broken-winged fugitives to the same helpless condition. With a touch of the oar and a turn of the helm, the dead and dying sea-birds soon come floating alongside our boat, and now when it is too late we admire the rich and glossy green of their plumage, and wish that they were back again rejoicing in the sea and the sunshine. Mr St John, the distinguished naturalist and sportsman, had an affection for all varieties of birds and wild fowl as strong as his passion for bringing them to grief among the solitudes of Sutherland or on the shores of Moray. It may be difficult to reconcile the affection with the destructive propensity, but in the case of St John and others it had actually existed, although the curious combination of opposites may transcend the reach of our philosophy. If any apology be deemed necessary for the slaughter of the tiesties now described, let it be believed that their doom was sealed in the interests of science. For ourselves, although forming a portion of the fowling party on their sporting excursion, we must plead innocent to the charge of wanton indulgence in bird-murder on the island seas. Bang again! It is the rifleman once more bent on exterminating scarffs without any unnecessary waste of small shot. The old bird has come back to his former fishing-bank to give our friend with the rifle another chance of distinguishing himself among his companions in arms. A hit? No, the wily bird was fathoms down ere the bullet left the barrel, and yonder his rises far to the left, like an accomplished diver who has performed a Blondin feat under water, scudding over the surface, and looking this way and that with outstretched neck and making dubious, startled turnings to and fro. There is an attractive beauty in all the motions of sea birds whether they ride upon the waters in unmolested joy or paddle rapidly away in the agitation of alarm. Our rifleman feeling himself insulted by the old cormorant, has made up his mind to aim at no other kind of bird, and so he has taken up his station at the prow, where, with his finger at the trigger, he keeps a sharp and revengeful look-out for scarffs. Divers, guillemots, little auks, and great auks he leaves to the disposal of his friends, nor do we think that he would change his determination though one of the ancient eagles that formerly haunted the heights of Rousay should come swooping all the way from the camp of Jupiter Fring. Success at last crowns his resolution, and the blood of the slaughtered scarf incarnadined the waters.

We are now dropping smoothly across the Sound that separates Rousay from the west mainland. The island to which we are bound seems nigh at hand though yet some miles distant – this optical illusion being caused by the height of the hills. Hitherto our prow has been turned in the direction of Hullion, but now we put about in the direction of the Wire Skerries, as our amateur sportsmen are anxious to test their skill in seal-shooting. The skerries lying about the little island of Wire or Veira are favourite haunts for seals, and on sunny days they delight in basking in happy groups on the black rocks. By the aid of a good glass we discern seals on the skerries, but ere the boat is brought within comfortable shooting range they slide quietly down to their native element, the mothers carrying the infant seals on their backs, and some old fellows thumping the youngsters with their finny paws until they have tumbled headlong out of harm’s way. The seal is a comical fish, very affectionate and attentive to family duties, but alive to the slightest indication of danger, and fierce when wounded or driven to bay. We should not be surprised to learn that the progenitors of the seals were a tribe of Esquimaux who took to the water for warmth and finally settled down in their adopted element. The affection of the parent seals for their offspring is easily explicable on this Esquimaux theory.

After firing a salute over the skerries, whether in chagrin or in triumph it boots not to inquire, we retrace our course along Wire Sound, and hold on our way rejoicing for the little pier of Hullion. Listen and you hear a roar from the nor’-west, as if the Atlantic were about to burst down upon us with the thunder and tramp of irresistible waves. It is the Roost of Enhallow, swirling, tossing, and boiling in the ebb tide – a terrible sea-cataract from which unskilled navigators might well pray to be delivered. Our course, happily, does not lead us in the way of the Maelstrom, and here we are at last safely moored by the side of the primitive quay of Hullion, and ready to scale the ridges of Rousay. Our sporting friends are under the dire necessity of leaving their guns in the boat, as the gamekeeper is abroad, and the shootings on the island are preserved for the companions in arms of the gallant Major Burroughs, who is being bronzed at present by a warmer sun than that which shines upon his own Orcadian Isle. Rousay is well cultivated on its lower reaches along the sea-margin, and we have no sooner left the boat than we find ourselves among corn fields that promise to yield a goodly harvest. An excellent road runs round the island between the slopes of the hills and the sea-margin, and we strike away up the road in the direction of Westness. To the right the heights rise above us in successive terraces of strange formation, which look as if they had been subjected to glacial action, or tilted up at long=distant intervals by some volcanic agency. In truth, when surveying these terraces, rising one above another, and bearing a close resemblance to deserted sea-margins, it is difficult to resist the impression that Rousay has mounted to its present altitude by the successive upheavals of a subterranean force. There are volcanic indications about the island, and the inhabitants need not be greatly surprised although they should find themselves and their belongings tilted up fifty or sixty yards some fine summer morning before sunrise. It is not unusual for volcanic isles to possess a mysterious attractive influence upon lightning when thunder-clouds are brooding in the sultry air, and tenements in Rousay have more than once been struck and blasted by the electric fluid. High up the terraces on our right sheep are nibbling the mountain grass, and the call of the shepherd to his sagacious dog echoes faintly among the heights. Over one of the ridges a grey hawk is sailing, now hanging on motionless wings in the blue air, or swooping suddenly down upon his prey. On the left and in front we obtain a glorious view of the beautiful Sound between Evie and Rousay as we ascend the winding Highland road. The district of Evie wears a beautiful aspect with its green and yellowing fields and numberless farm and cottar houses basking in the pleasant sunshine. In the middle of the Sound lies the little island of Enhallow, with cattle grazing on its slopes. Between Enhallow and Evie the Roost boils and roars in the ebb, while at the mouth of the Sound, on the Rousay side, a still wilder Roost is in full play, pouring down with foamy breakers into the Atlantic. When the ebb-tide ceases to run and the flood begins, the Roosts are overflowed and make no sign. It is said that the native boatmen, by watching their opportunity, can pass between the Enhallow Roost and the Evie shore. Where there is a narrow run of smooth water, but we should be loathe to accompany them on any such dangerous expedition. The island of Enhallow is now deserted of inhabitants, and it must ever remain a mystery why families were tempted to take up their abode on a grassy sea-surrounded mound, which, from its position, cannot fail to be overswept by the Atlantic spray in December storms. The now deserted island has its own melancholy annals. Some seven families, it is said, resided at one time on that lonely spot, and when a fatal fever broke out amongst them, those who escaped infection fled from the isle, leaving behind them the dead and the dying.. This reminds us of incidents in the great plague which desolated London, and the mournful legend accords well with the present loneliness of Enhallow. Beyond this island, guarding the entrance to the Sound, Costa Head, that rises to the height of 478 feet, frowns darkly over the waters of the Atlantic, “marked with many a seamy scar” which tell of the veteran rock’s long contest with wintry storms. Beyond the Sound and far off in the parish of Birsay we see the gleam of a loch gladdening its solitudes.

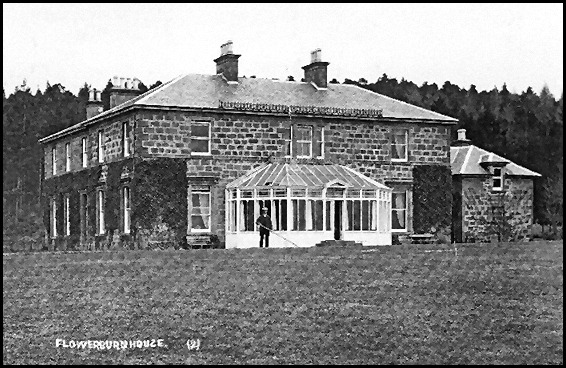

Below us now, at the foot of the steep slope, and on the margin of the waters stands the house of Westness with an adjoining farm-steading. There is an extensive garden and orchard attached to the house, on the cultivation of which much care appears to have been originally expended. The luxuriance of the trees and shrubbery takes one with agreeable surprise, although the garden has now for the most part been permitted to become a tangled wilderness. It occasions surprise that the remote and hilly regions of Rousay can produce grapes, and the wealth of flowers in the hothouses might astonish strangers who had only expected to find the heather-bloom or the Epiphobium augustifolium which haunts the burn at Trumland. The garden has a fine exposure, hanging on the slope full in the glow of the meridian sun, and it is defended on all sides with high walls from inhospitable blasts that might sweep from the hills or the sea. In front of the farm-steading and close upon the shore, there is a house of recent erection, which is used as shooting-quarters by sportsmen in autumn. The fields around Westness show traces of fertility and of careful cultivation. Farm servants, male and female, are busy at out-door work, and the expanses of corn have reached their transition state when summer green changes to autumnal gold.

Leaving Westness we strike up a steep and rugged path winding around the slope of a deep and secluded ravine. There is a queer, ancient-looking mill with its water-wheel which nestles snugly between the opposing slopes. The channel of the stream is dry, but the careful miller is hoarding for his own use the waters of one of the hill lochs for which we are bound, and the upraising of the sluice can at any moment enliven the ravine with the cheerful rushing noise of a headlong brook. There is a cottage, the beau ideal of an Irish cabin, hanging midway down the slope on the opposite side of the ravine, and a barefooted damsel standing in the doorway, empress of all she surveys, completes the secluded picture of still life. After climbing and stumbling up the rough primitive road for a considerable distance we gain the top of the gorge, and find ourselves on an undulating heathy plateau to the rear of the Rousay hills that front the mainland. We have thus succeeded in turning their flanks unawares, and in a short time we find ourselves in sight of the Muckle and Peerie Lochs, the locale of which has been indicated by a countryman. These lochs, or lochans, or tarns, are many feet above the sea-level, and lying in the heart of a waste heathy wilderness in the rear of the upper reaches of the hills, they present a singularly wild and desolate appearance. The largest of the two, which does duty as a dam to the mill in the ravine below, is fed by the torrents that seam the neighbouring ridges in days of rain and storm. A precipitous height in the immediate vicinity looks as if the half of its substance had been washed down into the loch by extemporised torrents and deluges of rain. Notwithstanding the darkness of the water – this being a characteristic of mountain tarns – these lonely lochs are said to contain some excellent trout, but so desolate do they seem in this uninhabited region of Rousay, that we may apply to them the poet’s words –

On passing from the lochs we, of course, make a point of inspecting the camp of Jupiter Fring. There can be little doubt that what presents the appearance of a camp is simply a natural ridge. We are bound to believe, because it is so written in the chronicles of tradition, that two large eagles haunted the camp “for ages,” but it is satisfactory to know that they were not Roman eagles left behind by Agricola. The name Jupiter Fring has evidently been given to the place by some Rousay dominie, who had a little learning, which is a dangerous thing. The camp is a hoax and delusion, and we advise all sensible antiquaries and sight-seekers to avoid it in future.

With labour, dire and weary woe, panting much and perspiring more, we gain at length the summit of a ridge on the south-west side of the island, and the magnificent far-spreading view is sufficient compensation for the toil that it has taken to reach the top. From the heights of Hoy you look down upon the Orkney Islands as from a balloon, and a somewhat similar effect is experienced on Rousay. The Islands seem to float about and around like portions of a semi-submerged continent, and they present such novel shapes that it is difficult to distinguish old acquaintances. Sitting down on the rich and rank heather, and lighting hookah and cigar, we enjoy the delightful spectacle in peace and at ease. Shapinsay, Eday, and the rest lie like low rafts on the water, while Gairsay, nearer at hand, presents a striking resemblance to a drifted hill. Indistinct in the distance, for a haze is beginning to gather, we see the blue smoky glimmer of the capital of the Orcades. Hoy we salute as he looms up, grandly on the horizon. Below us the Sound, laying the chequered fields of Evie, has narrowed to a stream, and turning round we front the grand expanse of the mighty Atlantic, and feel that our trip had not been in vain if we had only, from this elevation, been permitted to gaze some more on that ocean spreading away and away till sea and sky commingle in the west.

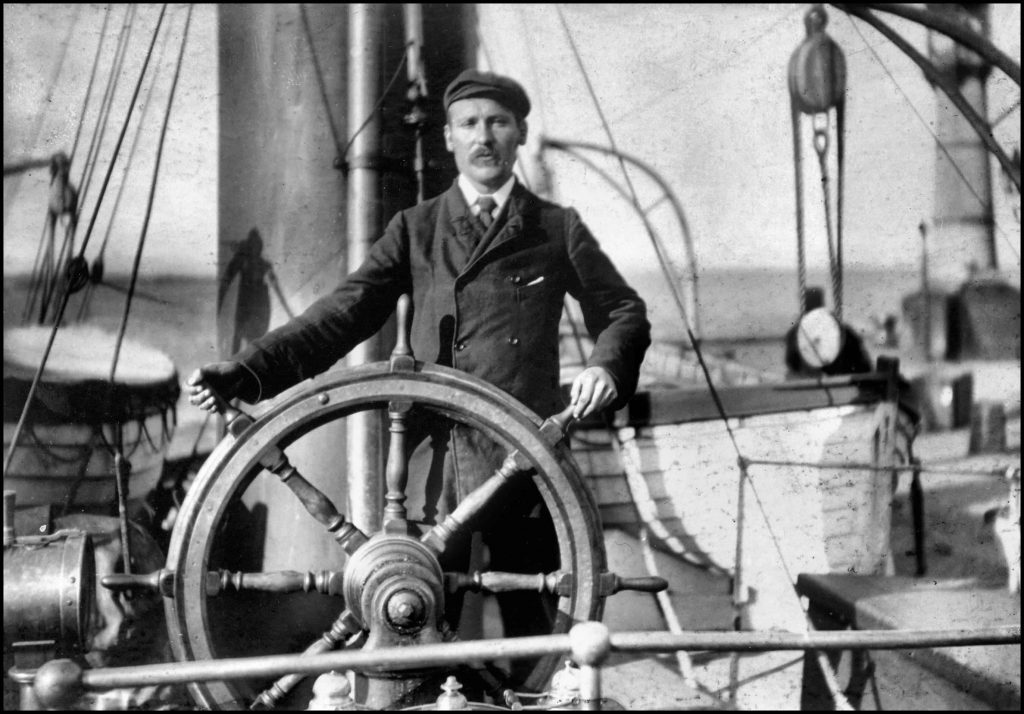

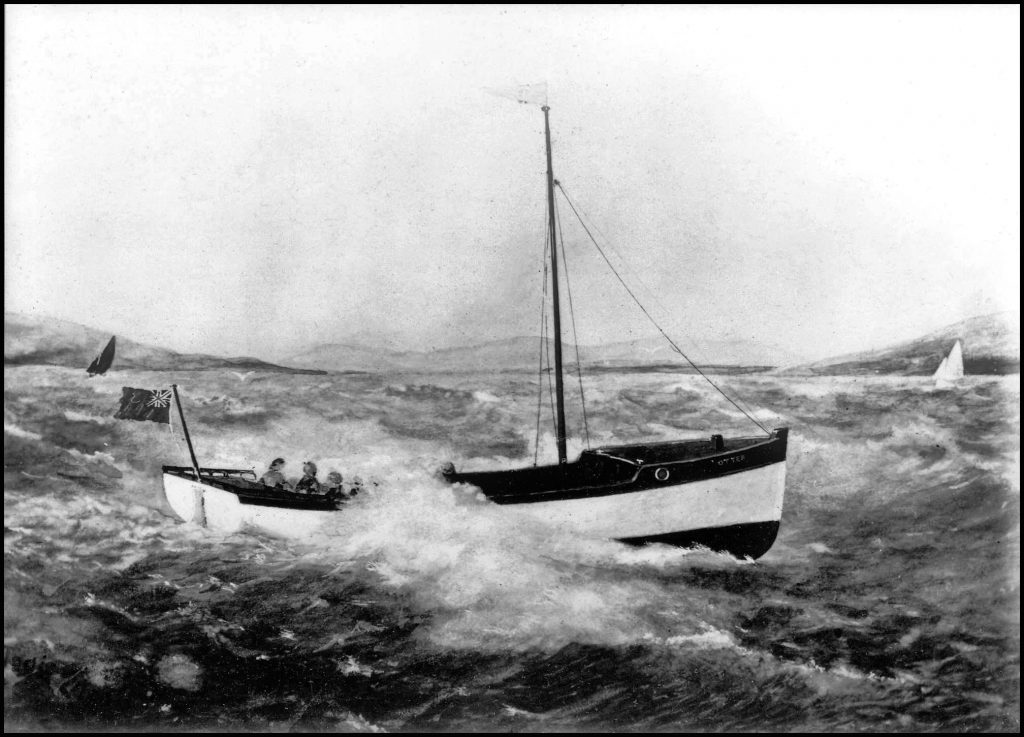

While warning the tourist to avoid the Camp of Jupiter Feriens, we urge him, if he admires the picturesque, to climb the summit of a Rousay ridge. Following the road to the nor’-west of the island he will find some wild and desolate coast scenery, and let him not forget to visit the loch of Saviskaill. Wild ducks there abound in numbers that would rejoice an old sportsman’s heart. Above all we advise him to remember the commissariat, for the pangs of hunger and thirst are now upon us, unprovided as we unfortunately are with wallet or flask, and so there is nothing left for us but to retrace our steps hastily to Hullion, where a hostelry is said to exist among the corn fields. Nearly opposite the pier, where our boat rocks impatious, there is a pathway leading through a patch of fine oats. At the end of the path is the welcome haven, where we refresh our inner man with such provender and temperate liqueurs as the island affords. It is a queer but comfortable upper room into which we are shown, and the good lady of the house does her best to supply a sufficient quantity of beer and biscuits to her unexpected guests. While sitting here enjoying our ease in our inn, there comes a sudden message from our worthy skipper, who has been putting the tackle of the boat to rights, urging us to hasten our departure as we have a lengthened sail before us, and the shades of a “dirty” night are beginning to fall. There is no use of attempting to account for Orkney weather. The beautiful day is rapidly settling into a rainy and gusty night, and the craft that must convey us to Kirkwall is not the best adapted for riding down the tides that will beset our pathway on the sea. However, we stow ourselves on board, and coats and plaids are speedily in requisition as the sky is thickly overcast; and the rain, which is intent on accompanying us home, has already begun to fall. We have faith in our wise skipper who has handled the tiller often before. “Keep a sharp look-out,” says honest Master Mainland, as we leave the little pier, and we are soon dashing through the swell and spray of the troubled Sound. “A yawl would have served us better tonight,” says the skipper, as the mane of a wave tosses in at the prow and its wet tail splashes over the bulwark astern. The boat does not rise to the sea, but after two bagfuls of heavy ballast have been cast overboard, we take the waves with a lighter bound and glide more lightly along. Thus we hold our own and hold on our course, tacking onwards and upwards to Gairsay, getting gradually soaked with the fast descending rain, and occasionally soused with an unexpected splash of spray. We skirt the edges of some of the wilder jumbles of tide in the vicinity of Gairsay, seeing the white and troubled crests of the waves tossing in the glimmering light, and thus by cautious tacking and a steady hand at the helm, and with Providence for our guide, we steer at last into smoother water, and feel ourselves more at home when the flickering lights of Kirkwall gleam through the rain like numberless beacons. Again we are under the lee of Her Majesty’s ships which shine forth a cheerful glow from cabin lamps, and once more, as the chimes of St Magnus strike an hour from midnight, we pass silently between the portals of Kirkwall harbour, thoroughly satisfied with our fowling excursion to Rousay.

© BRITISH NEWSPAPER ARCHIVE