by

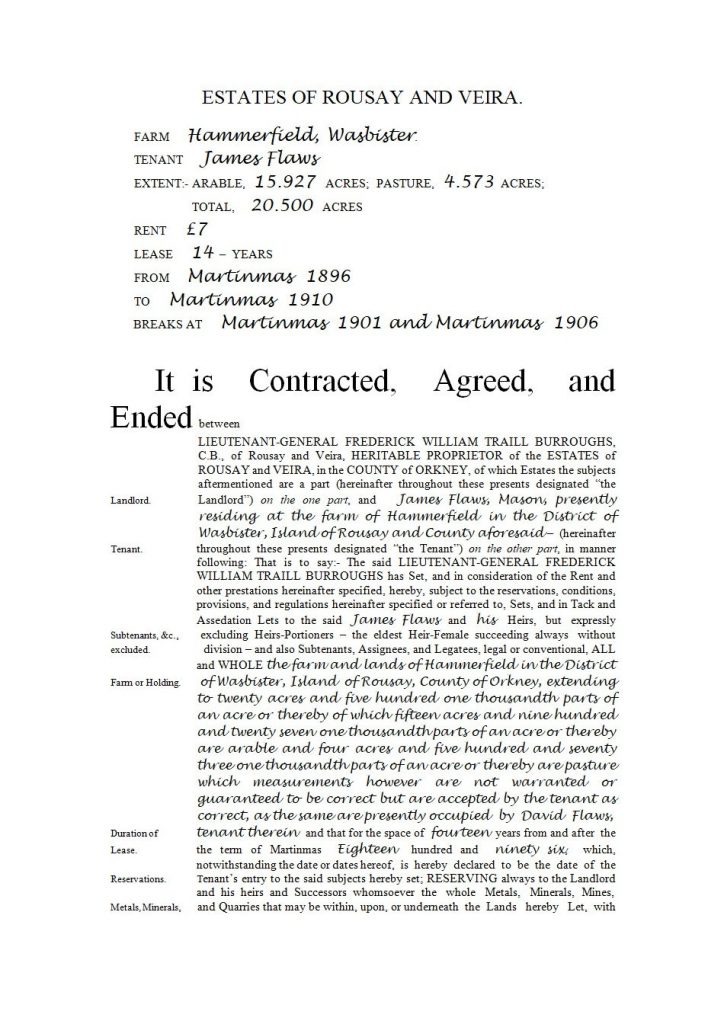

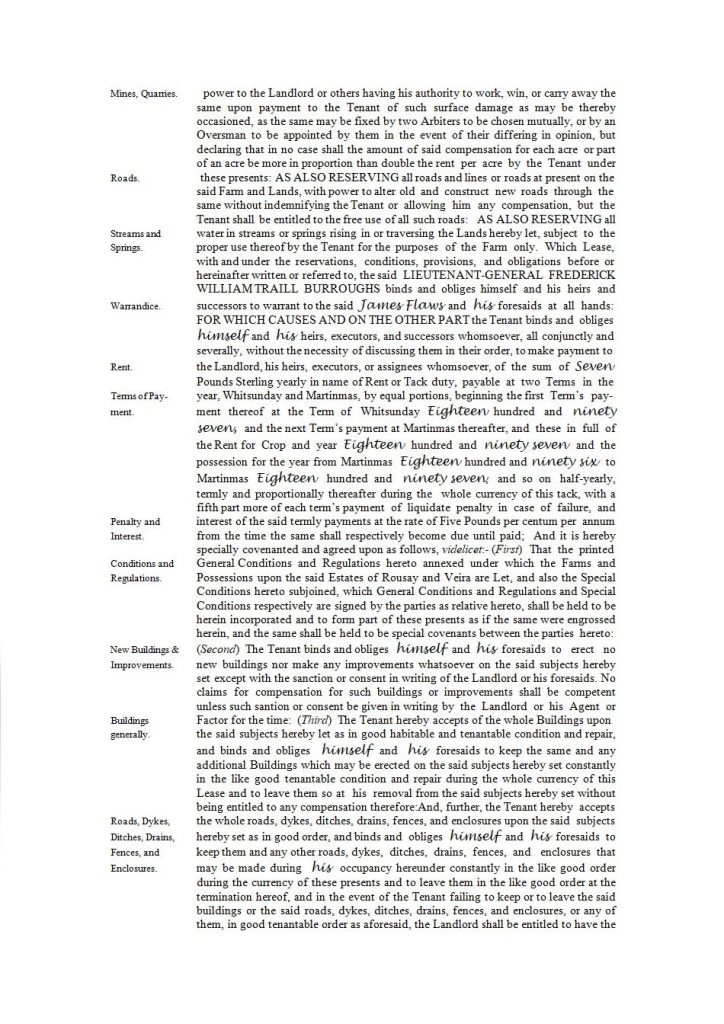

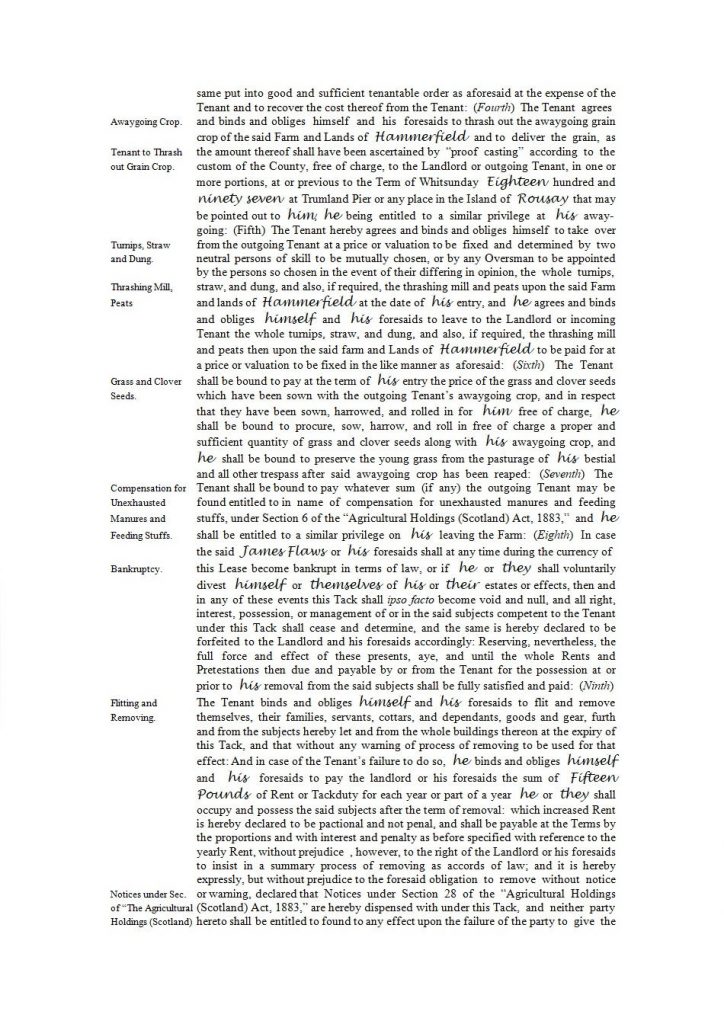

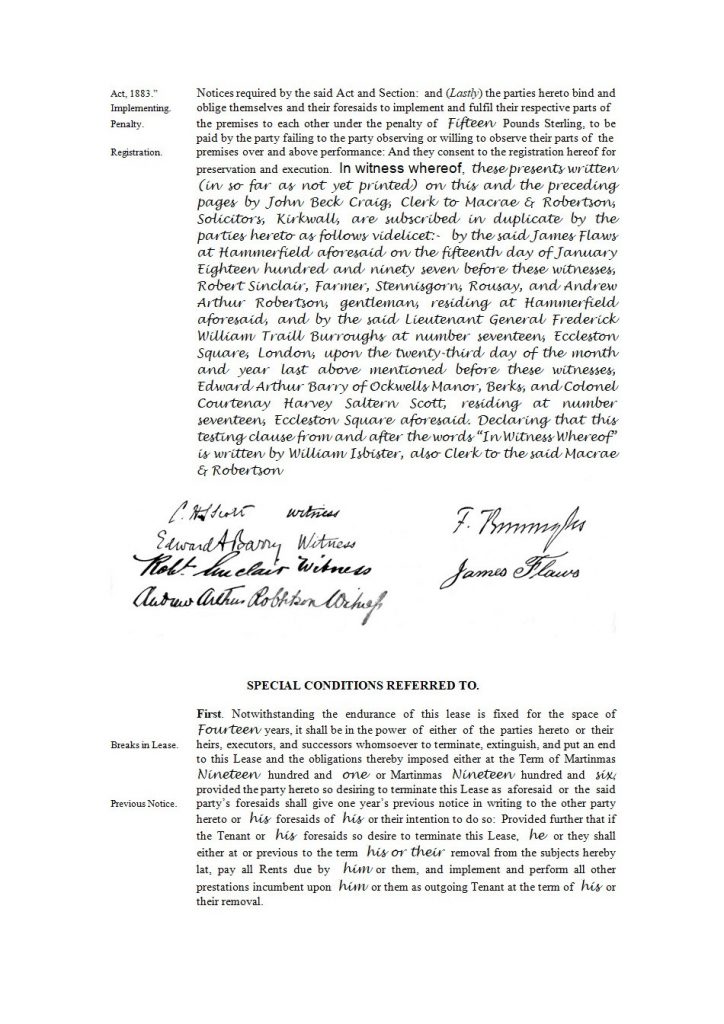

HUGH MARWICK

KIRKWALL, 8th NOVEMBER, 1923.

Though undoubtedly one of the most picturesque islands in Orkney, Rousay is not, in the eyes of an antiquary, by any means the most interesting. Even to-day the greater part of its surface is covered with heather and in early days it can have offered but few attractions to the primitive agriculturist in comparison with the lower-lying and more fertile islands of the group. Round the skirts of the isle, however, there are signs of cultivation from very far-off days; nor are indications lacking that the island was inhabited thousands of years earlier still for how long exactly it is impossible to say until we have learned to read more intelligently the memorials left behind by these nameless folk of long ago.

STANDING STONES AND CHAMBERED MOUNDS

Of these memorials, the standing stones and the chambered mounds form two groups that are among the oldest of all. The relative antiquity of each I shall not attempt to determine; suffice it to say that both are supposed to date back to the early Bronze Age of this country, if not to the still earlier Neolithic. Today, only two of these standing stones remain erect – one on the roadside in Frotoft beside a house named after it – Longsteen, the other on the south-east slope of the hill to the north-east of Faraclett. The Long-steen [below left] is about seven and a half feet high by two feet three inches broad at the base, tapering to slightly under two feet at the top, and varying from about eight inches to eleven inches in thickness. That at Faraclett is about seven feet high, with a fairly uniform rectangular section of five and a half feet by one and a half. It is known as Yetnessteen [below right], i.e., O.N. Jǫtunna-steinn, ‘ stone of the giants.’ Obviously the stone was as mysterious to the Norsemen when they came over as it is to us, and they ascribed its erection to the giants who figured so largely in their mythology. But there it still stands, and an old island tradition tells how on each New Year morning, immediately after midnight, it is wont to take a trip down the slope for three hundred yards or so to the Fresh-water Loch of Scockness – covering the distance in two steps – have a drink, and then return once more to resume its lonely vigil.

In his Tour Through the North Isles of Orkney (in 1778) Low makes mention of this stone and another at Westoval. He does not mention the Longsteen in Frotoft, and, hence, in the Old Lore Miscellany, Vol. VIII., Pt. 111., where the Tour was published, an attempt was made to identify the Westoval stone with the Longsteen. On the northern slope of Blotchniefield, however, just above the fence near which most of the Sourin peats are now cut is a ridge known as Steenie Vestifal, and, though no standing-stone is apparent now, there is no doubt that this is the place to which Low refers.

Indication of a fourth stone may be found, I think, in the farm name – Stennisgorn. Gorn represents O.N. gardðr, a farm, and though the first part of the name may be a personal name – Stein(s), it is more probable that the reference is to a standing-stone near. This is supported by the same name in Birsay – now pronounced Stanger (sténdzer). In the 1595 Rental this is spelt Stansgar (in Peterkin’s edition), and Stainsgair (in the copy in the Sheriff Court House, Kirkwall). Close to this house is the solitary standing-stone of Qweebuin (hwibon). The earliest form I can find of the Rousay house name is Stennisgar, which occurs in a deed of 1578 – for a note of which I am indebted to Mr. Storer Clouston. In the Uthell Buik of 1601, we find a Stevin Stennisgair in Wasbister, Rousay, who was evidently the farmer in this house. Hence the presumption is that both the Birsay and the Rousay name arose from a similar reason – the proximity of a standing-stone.

What the original purpose of these isolated stones has been no one can now say. They may not all even have had the same purpose, but, in some cases at least, there seems no doubt that they have been connected with the worship of what Dr. Craven, in his History of the Church in Orkney, Vol. I., p. 3, has termed the ‘generative powers in Nature.’

[The images above show the location of the Taft o’ Faraclett at the northern end of the Loch of Scockness.

The lower photos show the Taft, and a rope to aid the adventurous in exploring its subterranean chamber.]

Of chambered mounds, or picts houses as they are called, it is difficult to say how many specimens are to be found. There are several mounds still unopened which may be of this class, but, so far as I know, only three have been opened. One of these is at the north end of the above-mentioned fresh-water Loch of Scockness, in a small park known as ‘The Taft of Faraclett .’ An account of this, by Mr. John Loutitt, may be found in the O.L. Miscellany, Vol. IX., pt. I.

[The original entrance to Taversoe Tuick. Once inside from today’s ‘modern’ entrance one has the ability to clamber down into the lower chamber…..]

Another example, discovered on the top of a hillock called Taiverso, near Trumland, showed the usual features of a relatively long entrance passage and central chamber. Opening off this chamber were small recesses in which were found the remains of human skeletons. On the point south of Skaill on the Westside, a third specimen of this class of mound is said to have existed.

BROCHS

The next group of antiquities – that of the brochs – is generally reckoned now-a-days to be much younger than those we have just mentioned. Into that vexed question, however, we need not enter here; I shall merely indicate the sites in Rousay where brochs have stood. On the Frotoft shore, a few hundred yards west of the Longsteen, stand the ruins of one still bearing the name Burrian (i.e. O.N. borg-in, the broch). This has been dug into but never properly excavated. At Brough on the Westside is the site of another, from which the house has its name. A few hundred yards west of this, on the edge of the cliffs – flanked on each side by a long narrow geo – is the Midhowe, a mound that pretty certainly conceals a third. Then, on a small islet, called Burrian, in the Loch of Wasbister, we have the site of a fourth, which has been approached from the shore by means of a causeway or stepping stones.

Besides these, there are other mounds that look like broch-remains. One at the shore, between Nears and Hunclett, called the Knowe of Hunclett, is almost certainly such. A very similar mound is to be seen at Viera Lodge, and the Knowe of Lairo – near Hullion – is very likely a third.

None of these sites has been properly excavated, though one at Brough has apparently been opened at one time. In an account of a pleasure-trip from Kirkwall to Rousay recorded in The Orkney Herald of 26/7/1870, some mound is thus referred to: “About the same locality (i.e., the Westside) are a couple of mounds commonly designated Picts Houses or Broughs. One of them having been partially-explored, we were able to enter what seemed to be the principal apartment, from which there were at least two entrances to other passages or chambers, but from neither of which the earth and other debris had been cleared.”

The distribution of these broch-sites is also instructive. They are all at or near the shore, and are surrounded by the best land in Rousay. This in itself suggests that the broch~builders were cultivators of the soil, and to support this view one has but to point to the quern-stones found in practically every broch which has been excavated. It may be argued quite well that these querns have been used by inhabitants of much later date than the builders, but one is still left with this noticeable coincidence of the sites with the best land.

GERSTY

In my Paper last session on Sanday, I dwelt at some length on these puzzling structures known as Treb Dikes. In Rousay that name is not known, but one at least of these earthen rampart-like structures is to be seen still, running down from the public road to the shore a short distance up from the Leean Slap of Langskaill. It is strikingly green as compared with the adjacent ground, and goes by the name of the Green Gersty, i.e., ON. garð-stœdi, dike-steethe. The land around is not cultivated, now at any rate, and no tradition of its use or origin is extant. Hence, and also on the analogy of the Sanday Trebs, one is disposed to regard it as a memorial of the pre-Norse population.

CELTIC NAMES

As I have dealt elsewhere with the Celtic element in the place-names of Orkney, I shall not linger here on those Rousay names which seem to me to have been given by that earlier race which the Norsemen conquered and assimilated. These names are among the most difficult that exist, and certainty about them is hard, if not impossible, to attain. But such names as The Camps of Jupiter Fring – a ridge on the northern slope of Blotchniefield, Marlaryar – a hill above Hullion, and Cannamesurdy – a well on the beach in Frotoft – seem to have no Norse semblance at all, and may with tolerable assurance be ascribed to the earlier Celtic race.

EARLY NORSE SETTLEMENT

It would have been intensely interesting if the writer of the Orkneyinga Saga had given us an account of the first settling of Orkney similar to that we have of the first colonisation of Iceland. The fact that he does not, suggests that the settlement had been made so long before his day that he knew nothing about it. In Nordiske Minder isœr sproglige paa Orknøerne, Dr. Jakobsen mentions a Rousay legend, which he was told by Mr D. J. Robertson. According to this, when the first Norsemen came to Rousay they were confronted at landing by strange elf- or troll-like beings who marched down against them – armed with glittering spears. In such a curious fashion has been perpetuated the first meeting of the Norsemen with the alien Celtic race.

Who the first Viking to set foot on Rousay was, we do not know. One would fain like to identify the Rolf (Hrólfr) whose name is commemorated in the name of the island – Rousay, Hrólfsey – with Torf Einar’s half-brother of that name – the famous Rolf who founded the Norse power in Normandy, but for that one has no justification at all. It is known that he went from Norway to the Hebrides and must thus have visited Orkney en route, but it is probable that the Orkneys were settled some generations at least before the great Viking age, and that had begun nearly a hundred years before his day.

Rousay in July 2007 during her voyage from Roskilde in Denmark

to Dublin – near where the original vessel was built c.1042.

Besides the unknown Rolf, the names of a few other early settlers may be deduced from the farm names. The present farm-name Innister appears to be a corruption. The name does not appear in any of the early rentals, but in a deed of 1664, recorded in David Forbes’s Protocol Book, we find Rowland Insgaire in Insgaire. In the Valuation of 1653, thls gentleman evidently appears again as Roulland Ingsgarth. In a deed of 1671 the name appears as Ingsgair, and even as late as 1799 Innisgir in Wasbister is found in the Register of Births. By some strange accident the house name has now become Innister and the surname Inkster. The original form is doubtful, but almost certainly the first syllable represents a personal name.

A clue to the original form of Hurtiso, a farm name in Sourin, is to be found in the 1492 Rental where Hurtiso, in Holm, appears as Thurstainshow, i.e., Thorstein’s mound..

The first syllable in Knarston is almost certainly also a personal name. In most cases in Orkney tunship-names, the termination -ston, which represents the dative plural of staðr, a stead, settlement, ‘tun,’ is suffixed to a man’s name, and this is unlikely to be an exception. There are two names suitable Knǫrr and Narfi – and, as old forms of the name regularly show the initial K-, the former is to be preferred – Knarrar-stǫðum, the settlement of Knorr.

Avalsay appears in both the 1500 and 1595 Rentals as Awaldschaw. The first part of the name represents a man Augvald, and judging from the analogy of Horraldshay in Firth, which the 1500 Rental spells Thorwaldishow, and the 1595 R. Horraldsay and Horraldshay, we conclude that the Rousay name has been Augvaldshaugr, Augvald’s mound.

Lastly, in Frotoft we have a form that points to an earlier Froða-topt, the site of a house of a man Froði. Munch suggested that the word must have been Freys-tupt, the site of a temple to the god Frey, but that is not in accordance with the phonetic development.

These four men – Froði, Augvald, Knǫrr, and Thorstein – were in all probability among the earliest Norse settlers in Rousay; they may even have been among those who were challenged at landing by the ‘glittering spears’; but to us to-day, none of them is other than a pale shadow of a name.

A few place-names still remain to show that in these days Rousay was not so devoid of trees as it is at present. Scockness is most probably an O.N. Skogar-nes, the ‘shaw-’ or forest ness, and the old house name Skuan in Sourin and the field Skuanie in Wasbister point unmistakably to the same feature. Probably it was rather brushwood than real forest, but these names show conclusively that there was something of the sort.

SIGURD OF WESTNESS

In the Orkneyinga Saga, only one Rousay family – that of Sigurd of Westness – figures at all largely. If, as has been surmised, the author was Bishop Bjarni, we need not be surprised at the prominence given to Sigurd, for his wife was Bjarni’s grandaunt – a niece of Jarl Hakon Paulsson, and grand-daughter of Jarl Paul Thorfinnsson. Nothing is known of Sigurd’s own ancestry, but he was one of Jarl Paul Hakonsson’s closest friends and supporters – his wife being a cousin of the Jarl. They had two sons, Hakon Pik and Brynjulf.

SITE OF OLD WESTNESS

Whether the Westness of Sigurd’s time was at the site of the present Westness House may be doubted. For one thing, there is no ness at the present house to justify the name. It is probable that the whole promontory on the west side of the island – terminating at the south-west corner in the bold and majestic Scabrae Head – formed the original West Ness. At all events, Scabrae was included in the old Outer Westness of the early rentals. Approximately half-way between the present Westness House and Scabrae Head stands the old house of Skaill – quite close to the beach, with the old parish church adjacent. Just outside the church-yard wall are the ruins of an old building, and a few years ago, Mr. Storer Clouston discovered here the remains of a square tower or keep with walls about eight feet thick, enclosing a room nine or ten feet square. Excavation would be necessary to reveal the exact size, but these figures are approximately correct. The stones used in the building are massive, and have been well laid in lime.

In a charter of 1556 of the sale of the lands of Brough in Rousay by Magnus Cragy to Magnus Halcro, specific mention is made of a fortalice which went with the property. In all probability, the present ruin represents that building.

Old people on the Westside knew of this ruin by the name of the Wirk (i.e. 0.N. virki, a fortification), and a legend existed that it was built as a stronghold in which to keep a beautiful woman whom the builder had taken a fancy to and carried away forcibly from her friends.

What element of truth is in this legend we cannot say, but the very close correspondence of the building with that of Kolbein Hruga’s fortress in Weir is striking. According to Wallace’s account of the latter building, it also was not more than ten feet square inside, had very strong walls about eight feet thick and was built with lime. Mr. Clouston is thus strongly of opinion that both buildings are more or less contemporary. We know that Kolbein built the one, and the great probability is that the other was built about the same date by his kinsman Sigurd. If that be so, we have another weighty argument for locating Sigurd’s home at Skaill.

CAPTURE OF JARL PAUL

More than ordinary interest attaches to the site of Sigurd’s house, for it was while on a visit to him that Jarl Paul Hakonsson was suddenly kidnapped by Sweyn Asliefson and borne away to end his days – no one knows how or where.

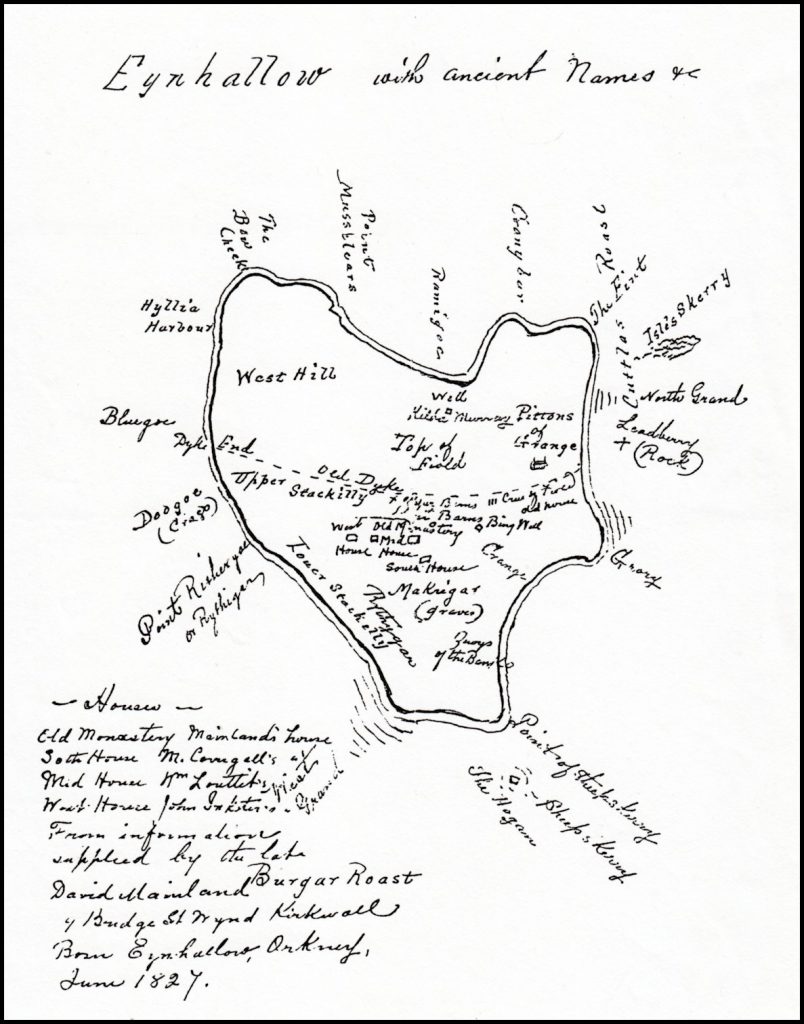

At this stage the Saga narrative becomes very puzzling, and is not in accord with known facts. It is stated that Sweyn came round the west of the Mainland and by Evie Sound towards Rousay. As Evie Sound, nowadays, is applied only to the sound inside Eynhallow, one would be led to believe that Sweyn came inside also. But we are then told that Sweyn sailed towards the ‘end of Rousay’ where there was a big headland (hǫfði), underneath which was a mass of stones where otters were often to be found. The ‘end of the isle ’ and the ‘big headland ’ can only refer to Scabrae Head, which, be it noted, still retains the name Head. This, however, is outside – to the north-west of Eynhallow, and to approach it from the west one would not pass through the present Evie Sound at all.

Another difficulty arises when we read that the Jarl and his men had gone ‘south along the island’ that morning, to hunt otters at the place just referred to. Now, whether Sigurd’s house was at Skaill or at the present Westness, the way to Scabrae Head would be north rather than south.

This confusion regarding the scene of the Jarl’s capture is a strong argument against Bjarni’s authorship of the Saga, for he, having been bred in Weir, must often have visited his relatives at Westness and been perfectly familiar with the place – especially a place associated with such an event as the capture of the Jarl.

At the head of a small bay a little bit south of Skaill there is a mound known as Swandro, around which, according to Barry, are to be seen graves formed with stones set on edge. From this fact, and the apparent similarity of Swandro to Sweyn, Barry and others have thought that this may have been the scene of the fight. For that view there seems no justification. In Vol. X. of the Proc. of the Society of Antiquaries, Dr. Joseph Anderson gave an account of a Viking sword and shield boss found near here, but he was disposed to think that they dated from a century or two before Sweyn’s time. The place, too, is over a mile from Scabrae Head, and if any man’s name were to be attached to the scene of the struggle it would be Paul’s rather than Sweyn’s. And by that time also, when Orkney had been Christianised for over three generations, burials would have been more probably made in consecrated ground. The Bishop visited Westness immediately after the event.

SWEYN’S VENGEANCE

One other vivid Saga scene in which Sweyn figures is laid in Rousay. After the death of Jarl Erlend, Sweyn, it is told, went to Rousay. With five men he climbed the hill and went down to the shore on the other side – where exactly we should dearly like to know. In the dark “they concealed themselves at a certain farm where they heard a great talking going on. Thorfinn and his son Augmund were there, and a son-in- law Erlend. Erlend was holding forth to his kinsmen that it was he who had given Jarl Erlend his deathblow, but they were all of them of opinion that they had borne themselves well. When Sweyn heard that he leaped into the house at them, his fellows coming behind. Sweyn was quickest and dealt Erlend his deathblow forthwith. They took Thorfinn away with them prisoner; Augmund, too, was wounded.” It is a commonplace tale enough – told without any form of embellishment, and yet how the scene lives for one down the centuries!

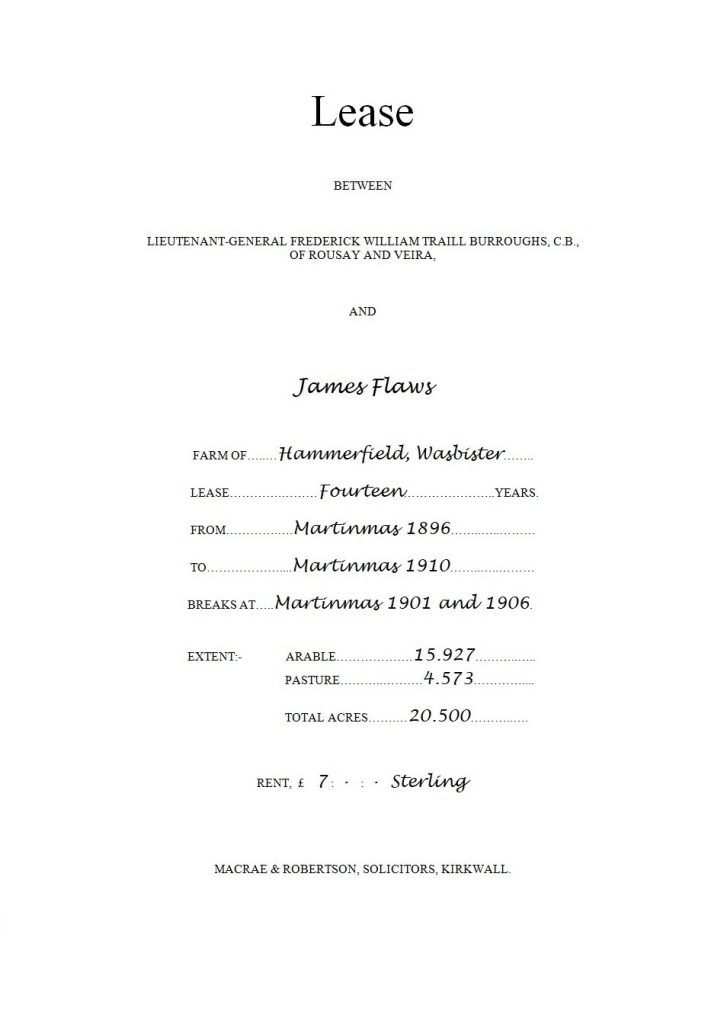

URISLANDS

At what period exactly, the skat tax was imposed on Orkney is not known, but, for that purpose, we learn from the old Rentals that Rousay was divided up into 6½ urislands or ouncelands. These were as follows :- Scockness ½; the rest of Sourin, north of Knarston 1½; Knarston (including Avalsay), Trumland, Over and Nether Hunclett, Frotoft, Corse and Inner Westness were a ½ urisland each; Outer Westness (Skaill & Brough). Whome, & Quandal was 1, as was Wabister (excluding Langskaill), and Langskaill itself was a ½. Total urislands 6½.

and Howdis Meadow in the right foregound.

PRESENT DISTRICTS

These divisions do not retain their individuality as of old. Scockness, Knarston, and Avalsay are now all reckoned in Sourin; from Avalsay to Trumland is known as the Brinnian; Frotoft now includes the whole district between Trumland and Westness; Westness to Quandal – both inclusive – are sometimes referred to as the Westside, though Quandal – now a sheepwalk – still retains its separate identity; Wasbister now includes Langskaill also.

Thus, in each of the three chief districts of to-day – Sourin, Frotoft and Wasbister – there has been an extension of the districts originally included under these names. Wasbister seems to have swallowed up two others at least. The termination ‘bister’ (O.N. bólstaðr, a settlement) is very common in Orkney, applied sometimes to a single farm and sometimes (as probably originally) to a whole tunship. In the present Wasbister there is a house up in the hill still called Everybist, i.e., yfri-bólstaðr, the ‘upper bister.’ But there was another bister in the district formerly – Libuster – a name which appears frequently in old documents, but is quite forgotten locally. It probably included the present Langskaill, as the park to the east of that house is still called the park of Lee, and the whole long slope east of that is called the Leean, i.e., O.N. hliðn, the slope. Hence we have a ‘bister’ on the slope, an upper ‘bister,’ and a West- ‘bister’ all included in the present Wasbister. Besides this, we know that the farm of Tafts went along with Wasbister Tunship, and thus a fourth district is added.

Sourin is a puzzling name. The old word was Sowrick or Sourwick, which means a muddy or dirty bay, unless Sour- be a contraction of suðr, south. But why this should have become Sourin, and the old form be totally forgotten locally, I cannot explain. It is just possible that the -in termination represents an O.N. vin, pasture, and that both words were current formerly, but that is very doubtful. What seems to have been in old days the main tunship or farm in Sourin has now disappeared altogether as an independent farm, but the name still survives, applied to a stretch of land on the farm of Hurtiso, and up on the top is a patch still called the Taft o’Husabae. The house nearest to this – Essaquoy – sometimes is referred to still as Husabae.

The site of the old Frotoft is also forgotten, but the probability is that it was somewhere about the present Hullion.

OLD CHAPELS

Mr. Clouston, in one of those invaluable papers contributed to the Scottish Historical Review, has pointed out how the old Orkney chapels are intimately connected with the old tunships. After the introduction of Christianity in the 11th century a considerable period elapsed before any regular system of parish churches appeared. The rise of these is wrapped indeed in considerable mystery. But, during the intervening period, well-to-do odallers built chapels for themselves, and one or other of these tunship chapels seems frequently to have developed into the parish church. Many of them, too had consecrated burial-grounds attached. When parish churches were established the sites were not always dictated by the general convenience of the parish. In some cases it would seem that the chapel of the most important tunship or the most prominent odaller became the chosen site. In any case that is what seems to have happened in Rousay where the old parish church was situated at Skaill. The church was dedicated to the Virgin, and there is a well close to it still known as Mary Well.

At the opposite extremity of the isle there was another old chapel in what is still the graveyard at Scockness. I have been told on good authority that in former days this was a place to which child-bearing women were wont to repair and pray. I can find no record of the dedication, but from the above practice one may suspect, this also to have been dedicated to the Virgin.

At the shore below Knarston is another graveyard called simply ‘The Cheppel,’ and at the shore near the pier of Hullion is yet another chapel site. These three sites thus represent the chapels pertaining to the old half-urisland tunships of Scockness, Knarston and Frotoft.

Wasbister is a nest of chapel-sites – no less than four being still known. One stood on a small peninsula called the point of Breetaness which juts out into the Loch of Saviskail on the east side. This name strongly suggests a dedication to St. Brittiva, Bridget, or Bride – which name in Norse is shortened to Brite. On the opposite shore stands the graveyard and chapel site known still as Corse Kirk – a dedication to the Holy Cross. A third chapel has been built, as so often elsewhere, on the site of an old broch on the islet in the Loch called Burrian. On some old maps of Orkney a dedication to St. Peter is marked in this part of Rousay, and one may suspect that this has been the spot. For the fourth site is an older dedication still. It is called Colm’s Kirk and is pointed out at the very verge of the shore down below Langskaill. This site must date from the old pre-Norse Celtic mission, and is thus by far the oldest church site in Rousay. Nothing of the walls is now to be seen, but stumps of stone are still visible and indicate a truly venerable spot.

GRANGE

In addition to these old chapel sites, there are a few other place-names that carry us back and give us a peep at the religious customs of our forefathers in pre-Reformation days. Just to the east of the house of Stennisgorn there is a field known as the Grange. This name is not Norse, but a borrowing from Latin through Scots or English. It was the regular name given to a farm or lands attached to a monastery or other religious house, and it appears twice elsewhere in Orkney – in Eynhallow and Paplay in Holm. We have no indication of the monastery to which this pertained; it may have been an outlying farm attached to the monastery of Eynhallow, visited and supervised by ‘outriders’ such as Chaucer’s monk. But as we have no information about it, speculation is idle.

PRAYER SITES

Praying crosses by the wayside were a familiar feature in old days and particularly at spots where the traveller came into view or lost sight of a church or holy place. In Rousay we have two, if not more, of these praying-sites commemorated in place-names. Corse in Frotoft is one of these, a house built near an old Corsegate or road to the church. In this case the church has probably been the parish church of Our Lady at Skaill, but it is not impossible that the spot to which pious eyes here turned was the more venerable church on the Holy Isle of Eynhallow. The house name Cruisday may have had a similar origin, but that is not so certain.

On the western slope of Mansmas Hill, the northern spur of the Ward Hill, a park just above the public road still goes by the name of Bonie Hole. This looks like two Scots words, but the name has no connection with either ‘bonnie’ or ‘hole.’ There is no hole there – bonnie or otherwise. It is the Norse bœnar-hóll, prayer-hill, the ‘Bonie’ being the same word that occurs in the common Rousay phrase for prayers – especially a child’s prayers at bedtime – bonie-words.

Thus, here again, we have another example of the same custom as we saw at Corse, and the church in this instance has also been apparently the parish church at Skaill. Somewhat farther on in Wasbister the old road to the church is remembered in the house name of Kirkgate.

MANSMAS HILL

Mansmas Hill is an interesting but puzzling name. It signifies the ‘hill of the feast of St. Magnus.’ No house bears the name to-day, but in the parish registers in the General Register House I discovered the name of a house in Rousay – St. Magnus Hill. I have heard no scrap of tradition about this hill, but it would seem that St. Magnus’s day, the 16th of April, was celebrated here in some fashion. As a local saint St. Magnus was held of course in the highest veneration in Orkney, and doubtless many ceremonies attended his festival. From the top of the hill, looking down the Sourin valley, one may see the famous old church in Egilsay that bears his name, and no doubt the exact spot of his martyrdom would have been well known and revered for many a long day. But beyond the name of Mansmas Hill itself, there is nothing left us to-day to tell us how the festival was celebrated.

GALLOWS

The methods of administering law and order in the old Norse days are very obscure but, arguing from what is known of other Norse lands, there were local assemblies or ‘things,’ as well as a central ‘thing’ for the whole group. In Rousay this would appear to have been held at a. place half-way up the Sourin burn, where a rocky knoll deflects the course of the burn and is half encircled by it. This place is called the Gallows. It is practically in the centre of Rousay and its name testifies to the summary methods of punishment in these downright times.

BAILIE COURTS, etc

After the islands came under Scottish rule, bailies and lawrightmen looked after local affairs. From old Bailie Court Records in the Sheriff Court Record Room we learn that about 1690 the Sourin district of Rousay, together with Egilsay, and Work and Carness in St. Ola, formed one bailiewick with Douglas of Egilsay (the owner of these lands) as bailie-principal. From one record we get a peep into local matters in that year. “At St. Magnus Kirk in Egilsay…..The Balzie (name not stated) continues James Craigie in Avilshay, Patrick Yorstone in Banks and John Allan in Faraclet as former Lawrightmen of Sowrick, and adds to them Magnus Banks in Cudraw.” There follow edicts requiring everyone to “keep their own cornland”; no one in Egilsay or Sowrick to take sheep “without the sheepman”; the people of both districts to pay a herd; the officer of Rousay has to keep an account of all beasts in Sowrick, and all dogs above a hundred are to be killed, except with special permission.

The following document, from the Sheriff Court Record Room, also casts some light on the duties of these officials and the need for such regulations:-

2/ Nov./ 1700

Proces and Judgement of Theift [blank] and John Brown writer in Kirkwall, Proc Fiscall of the Justiciar and Stewart court of Orkney for his Majesties interest contra Thomas Craigie in Suandall in the Island of Rousay.

That quhair by the Lawes and acts of Parliament of this and all other weill governed nationes the crymes of Stouth, pyckrie theift and reset of theift are abominable crymes, etc., etc. Yet true it is and of veritie that ye the said Thomas Craigie pannell Commone notorius theiff are guiltie of and have committed the said crymes In sua farr as about the space of twa yeires bygone or thereby George Craigie in Skoknes and Thomas and Patrick Allanes in Farraclett ransell men within the foresaid ylle Having at the direction of the Baillie gone in ransell anent several goods that have been stollen and having come to the pannells house and after ransell made there they did find about foure or fyve merks of gray whyt and black wooll which ye the said pannell could give no proof that the wooll was your owen or from whom ye had it.

Item ye are Indyted and accusd that about the space of a moneth bygone or thereby John McKindlay Patrick Yorstone and Thomas Allan in Farraclett thrie ransell men having Lykeways at the directine of the Baillie gone in ransell for some tedders that was stolen and having come to the pannells house as the person suspect and after ransell made be them they did fynd lying hidd in your kaill yaird ane kessieful of wooll and having enquired at you who hidd the same there ye told them that your wyfe had done the same and which ye the said pannell commone notorius theiff cannot deny. Item ye are Indyted & accusd that upon the same day when John McKendlay and the rest of the ransell men abovenamed were in your house ranselling for the tedders Margaret Robertsone spouse to Magnus Craigie in Sowrick was standing at the back of your barne keeping her kyne she did sie you the sd pannell come from your corne rigg upon great heast and did enter your barne and open the door thereof being locked and there did carrie out in your airmes ane lairge bound whyt sheep belonging to Hugh Marwick and did louse the sheep and put it to the fields at libertie for fear of being apprehended by the ransellmen knowing them to be ranselling in your house.

Item ye were Indyted and accusd that about the space of Twentie yeires bygone ye did goe to the hill and take ane sheep in the daytime and did bind the same and putt it in ane Swyne sty in the hill a little from our own house and in the evening ye desyred Magnus Banks now in trumland then your servant to take ane of your horss and to go to the sty and bring home the said ship to your house and when the fd. Magnus hadd come there and haveing looked to the mark of the said sheep he found the same did belong to some other person and not to you qrupon he came home agane and left the sheep lying in the same place.

Item ye are Indyted and accusd that when Sir William Craigie of Gairsey was Stewart and Justitiar of Orkney ye were enacted in the (Court ?) books for your good behaviour in all tyme therefter under the paine of Banishment.

Item ye are Indytted & accused That notwithstanging of severall acts made against you be the Baillie of Rousay dischargeing you to keep a sheep dog knowing you to be a man sub mala fama yet in contempt of authoritie ye still did keep ane or two sheep dogs and makes use of them as if the said acts had never bein standing in force against you. A—nd generallie ye are holdine and repute a commone notorius theiff be the whole Inhabitants of the Ille of Rowsay who has knowen you from your Infancie And therefore ye ought and should be adjudged to the death and your haill goods and gear both heretable & movable be escheate and Innbrought to his Majesties use in example and to the terror of others to committ the lyke in tyme comeing.”

………………

In spite of these terrible thunderings Thomas was only fined £30 Scots – to remain in prison till paid.

LEGEND

As in my former Sanday paper, I shall conclude with a few scraps of island tradition. You may remember that in that paper I mentioned the legend of “Cubbie Roo’s Burden” – a hillock said to have been formed by the stones that fell out of his kaisie when the fettle broke. Another legend is sometimes also fathered on Cubbie Roo. He is said to have been the giant who, from the top of Fitty Hill in Westray, threw a huge boulder at another giant on Kearfea in Rousay. The stone, however, failed to carry the distance and is to be seen near the shore in the Leean still. What are said to be his finger-marks are still visible in the stone which is known as the Finger-steen. As children we were told that unless we laid a small stone or some such object on the Finger-steen as we passed it, we should meet with trouble on our way back. An older name for this stone is, I think, preserved in the name of a fishing spot just below – Beya-steen. So far as I know, -steen is not used elsewhere as a name for a jutting crag such as this, and Beyasteen has thus, I fancy, simply been named from the stone above.

Another legend survives about a witch called Katho. This lady is said to have been churning in the house of Savaskail one day. She churned away harder and harder until at length the milk foamed up over the lid. She then stopped and exclaimed: “Tara gott, that’s done; Saviskeal’s boat’s casten awa on the Riff o’ Saequoy.” Sure enough at that time the boat was wrecked. The interest in this story attaches to the strange opening words. They are an old Norn phrase pat er gort, ‘ that is done,’ and it is curious to note how in the telling the phrase is immediately translated. Strangely enough, I have heard the same phrase used in connection with a Birsay story of a man who pushed his wife over the crags.

My last story is of interest to the naturalist as much as to the antiquary. On the top of the Brown Hill is a small tarn called Loomachun. This is O.N. lóma-tjǫrn, the tarn of the loom or red-throated diver. This bird in Orkney is known as the rain-goose. Some years ago I asked an old man if he had even seen a rain-goose. “ Yea’m I, boy, an’ I’m seen the eggs o’ her, too.” “Where?” I asked. “On the Loch o’ Loomachun.” The same year a friend of mine told me his son had found a nest of that bird at the same place a few weeks before. Thus, year after year, down the ceaseless procession of the ages, amid the tumult and change of human affairs, instinct has brought back this bird to nest by the lonely shores of Loomachun as it did when first the name was bestowed, and doubtless for long centuries before.

[Hugh Marwick ‘Antiquarian Notes On Rousay’,

Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society, Vol II, 1923-24, pp 15-21

(Kirkwall: Orkney Antiquarian Society, 1924)]