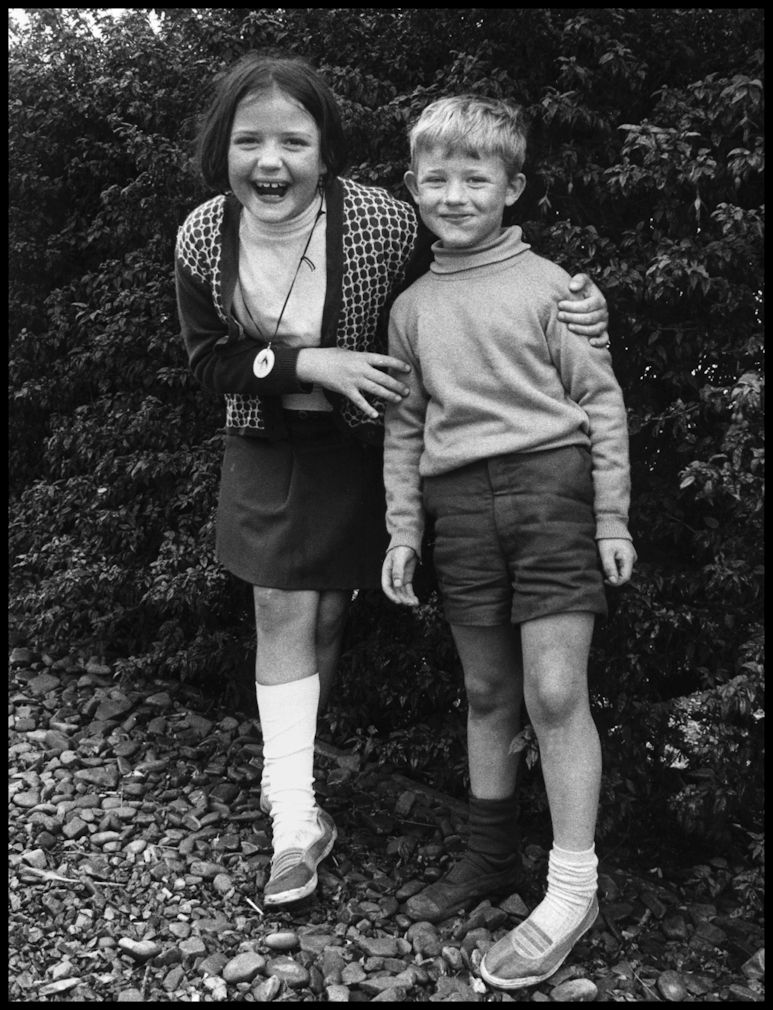

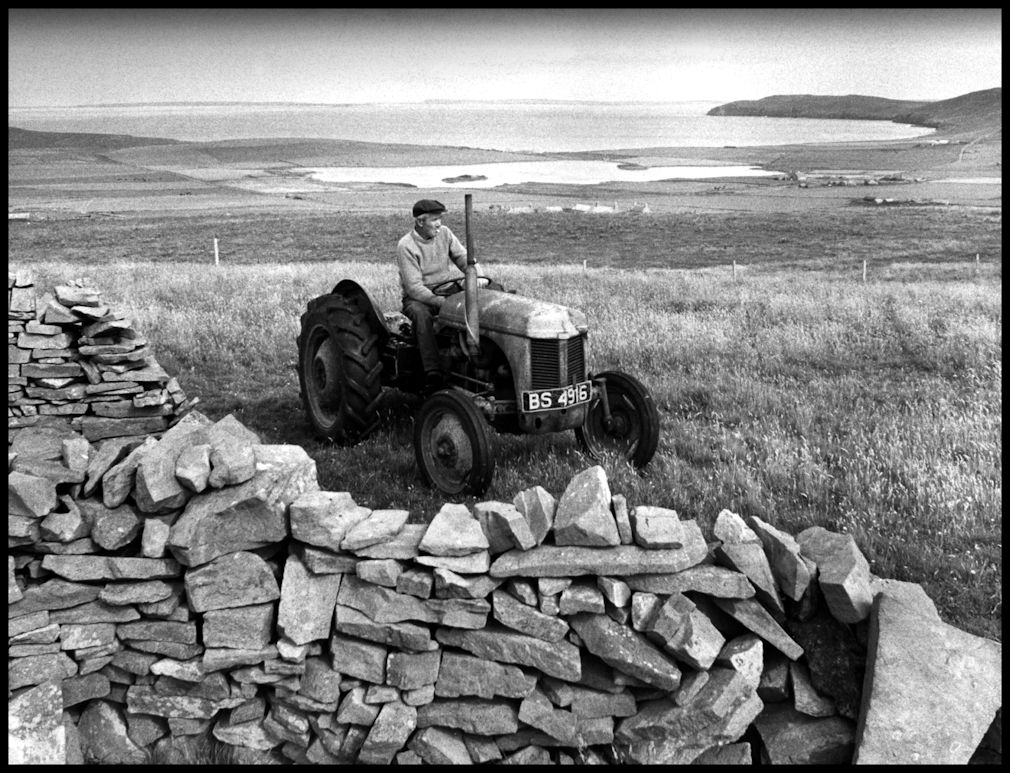

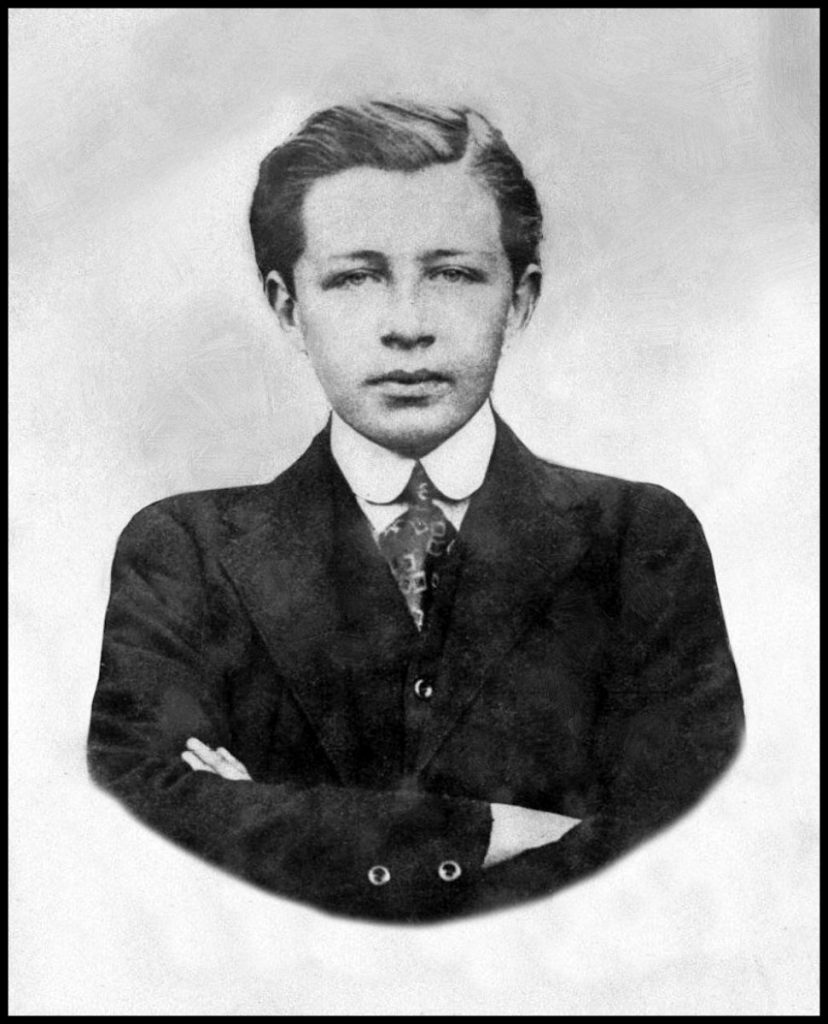

John Mowat, born c.1791, originally lived at Breckan but later at Innister, in Wasbister, Rousay. He married his second wife, Katherine Inkster [b. 1785], in 1814. They had six children: Christian was born in June 1815; Thomas in December 1816; Elizabeth in June 1820; Mary in September 1822; Hugh in December 1828; and Isabella in November 1830.

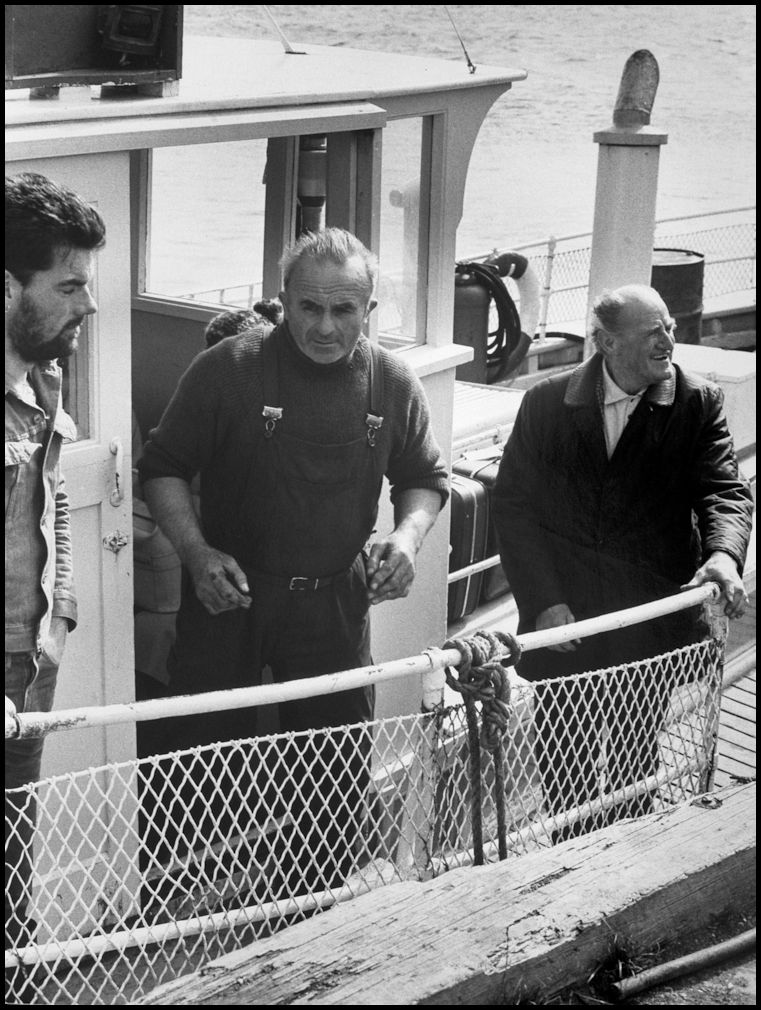

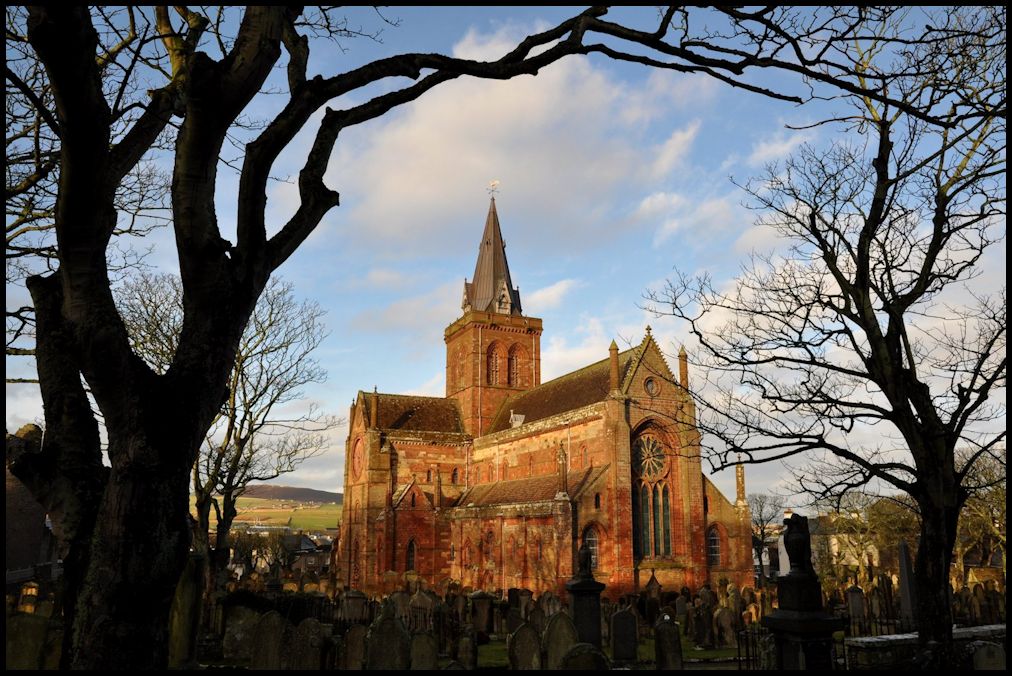

Hugh was 22 years of age when he signed on with the Hudson’s Bay Company in December 1850 and he sailed from Stromness the following year bound for the York Factory in Manitoba. From there he crossed Canada and was employed as a labourer at Fort Vancouver, a fur trading outpost and supply depot along the Columbia River that served as the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department, located in the Oregon Country. Hugh worked there from I852 to 1854, then was listed as a steward at the Vancouver depot from 1854 to 1860.

The following excerpt is reprinted with permission of the Publisher from Undelivered Letters to Hudson’s Bay Company Men on the Northwest Coast of America, 1830-57 by Judith Beattie and Helen Buss © University of British Columbia Press 2003. All rights reserved by the Publisher.

LETTERS TO MEN AT THE POSTS

The undelivered letters kept so carefully by the Hudson’s Bay Company do not include very many addressed to regular employees of the continental fur trade. As these men were usually long-term employees, who rarely deserted to find other work or left in the middle of their contracts, their whereabouts were not often in doubt and their personal mail usually reached them. Letters to them from Europe normally arrived in North America – as did the men themselves – across the north Atlantic Ocean through Hudson Bay to York Factory rather than by the south Atlantic route around Cape Horn to the Pacific Ocean. Columbia Department postings that required travel with the fur brigades by way of the river routes and mountain passes, however, effectively separated the men from the east by distance and time, and the chance of mail not reaching them was greater.

The letters to these men show concerns similar to those in many other undelivered letters. In a few cases, because of the longer career spans of the Company men, we have more information about their lives and are able of offer more detailed narratives, such as the tale of Chief Factor John Tod and his several wives. As Orkneymen are as plentiful in this sample as they were in the regular ranks of the Company’s employees, we have been able to access the excellent records of these island people to offer information on their lives after they left the Company service.

88 HUGH MOUAT: Your Mother is but tendar and very lonsom for yow always and hopes that yow will come home at the eand of your contrake if the lord spares yow to serv the time

Hugh Mouat joined the Company in December 1850, coming out on the annual ship to York Factory in the fall of 1851 as a labourer and travelling overland to work at Fort Vancouver. Letters were sent from home at the time of the year when Scots celebrate Hogmanay and try to be the first visitor in neighbouring homes. Such letters – like the one below – were filled with the many activities of the extended kin and friendship groups of Orkney. Hugh’s friend, John Inkster, was most concerned with keeping him up to date on the marriageable women.

Mr Hugh Mouat, Fort Vancouver Or else where, Columbia, Care of Secretary of the Honourable Hudson’s Bay Company

December 31 1851

Dear brother I take the plasant opurtunity of writing you this few lines to let you know that we are all in good health at prasant thank god for his mercies hoping and earnestly wishing this will find you the same[.] your uncle of e[y]nhallow and his wife and famely is well as yet we should be thankful for his mercies one and all of us[.] James Inkster my brother went of[f ] last march he went of to shields and engaged their with a baroque bound for quebec[.] he was a voyage their and back to shields again and then he left the ship[.] he was about a week their engaged with a brig going up the mediterranean a 6 month voyage[.] your mother and sisters is all well and Cirstinu is maried this winter and we have all got a weding at inisgar [Innister?][.] there was not many people at it all the people of cogar [Koogrew?] Jane Flett and James Craigie of hatherhall [Heatherhall] your aunt of grain John Inkster and peter from that was all from e[y]nhallow[.] this winter there is ben alterations is in e[y]nhallow[.] this winter there is ben a fever en it is been in william mainlands house[.] Jennet mainland left this world on sabbath night and william about 2 weeks after and it is been in william louttits house and harrjut is left this this [repetition] world so we have great reason to be very thantful that we are still spared a little longer in this sinful world[.] that should be a warning to one and all of us how uncertain our time is here[.] John mowat your brother is still unmarried yet[.] he is finely well in health[.] James Inkster wife and family is in good health at preasant thank god for it[.] John Inkster of pliverhall [Ploverhall] is home this winter[.] young John Inkster of e[y]nhallow was at caithness all the summer at the herring fishing and I had 3£ of wages[.] david and william mainland was to[o] and I was in skeal [Skaill] in sanwick [Sandwick] all the harvest i had 30 s[hillings] of mony for the harvest and i have been in gorn this two winters and Peter is in whis[.] Margaret Craigie is still in gorn and she is finely well her mother and all her sisters thy all put their kind compliments to you[.] margaret craigie of knarston she is not married yet[.] she put her compliments to the[e][.] she has no sweethart now atal simpson is still unmaried yet but he is not going to her at all – John Cl[o]uston girl is always coming To us she was used to do[.] magnus and bettsey and their mother is all well and magnus was at the herrin .shing in burra[y][.] hugh craigie of Death [Deith] and isabella and mary and John is all well at preasant[.] John Inkster and Jane craigie of gorn is both in good health[.] James craigie of blackhamers [Blackhamar] and barbara craigie of torbittail [Turbitail] is bucked [booked] but not married[.] all her sisters is married but Jane elin an of seventyfiver isabella a fine young lad in kirkwall – magnus cl[o]uston and John Inkster goes from the house every night to the girls[.] a fine lightsome winter in wesbyster [Wasbister][.] there is no fis[h] for John Cl[o]uston and hugh mowat[.] If you see william craagie [Craigie] margaret’s brother you will tell him to send a letter for it is 2 years since they received one from him[.] John craigie of hillion [Hullion] is married with sarah sinclair[.] John sinclair of news [Newhouse?] is built a new house but he is not married[.] George Leonard and margaret clouston is finely well and they have got another daughter[.] James Leonard is home this winter[.] cecelia is finely well[.] Margaret gibson flintersby is married this winter with James stenston a very grand wedding all the pecks of the island[.] you will send home all the news you ave if you got safe to calombia[.] I Have no more to say at preasant what remains your dear friend John Inkster

My Direction is

Mr John Inkster

E[y]nhallow to the care of Mr Hug [crossed out]

Mr Hugh Charles Evie

By kirkwall

Inkster was informative on whether female acquaintances were booked but not yet married, meaning that their intended fiancés had booked or arranged with a minister to have the banns of their marriage proclaimed in church. The “booking night” was an important one, because in an era before engagements it was the first indication that a marriage would take place.

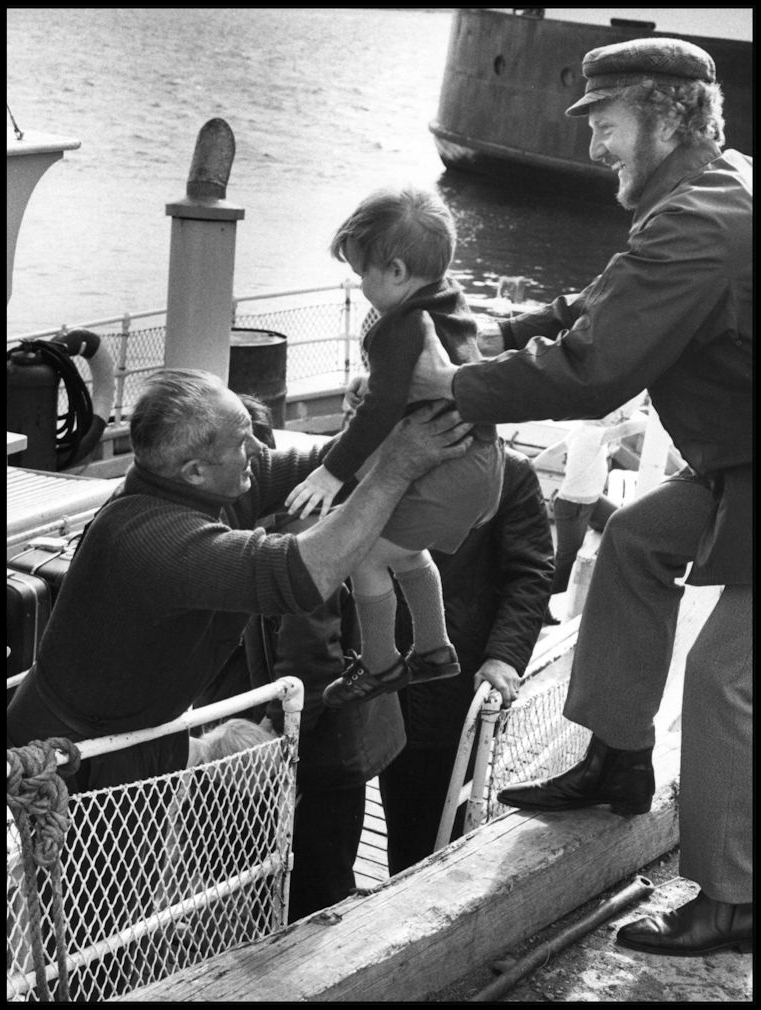

The fact that John Inkster’s brother, James, had within the previous year sailed to both Quebec and the Mediterranean, indicates the wide seafaring experience of the Orkneymen. They voyaged around the world but still liked to keep in touch with the doings of the folks back home. Hugh’s brother, John, also wrote to wish him well on New Year’s Day.

Mr Hugh Mouat, Fort Vancouver, Or else where, Columbia, care of Secretary of the Honourable Hudson Bay Company, London

Instar [Innister] Rousay Janury the 1 1852

Dear and loving brother I Embrace this oppurinntunity to let you know that we are all well at presant thanks be to god for it[.] Earistly woshing that this few lins yallaghe [crossed out] find yow in the same[.] we recived your wallcome latter the 23 october and wase glade to har that you ware wall[.] we recived your 2 latters and the bill that yow sent bout the Mony is not dra[w]n yet[.] your sister cirsty is got Married this wonter to man his name is william lutted [Loutit] and thy stop in firt[h] in chambar at preesant[.] he blong to rendal[l] and James simson and Markret gibson flintury is Married and black hammery [Blackhamar] barbery cray [Barbara Crey] is Married[.] this wonter we hade very good harren fishing and fine crop and it bene a fine wontar what is past[.] I have no pertlager News at presant but that we are all on the usualy way as when yow lefte us and the people tow send thir cind love to yow and Margret corger sisey vakrey send thir cind love to yow[.] so loving brother your sistars an all the famely of our others house send thire kind love to yow wishes yow well and I ame gone to stope till yow come home and get shire of my widden yet[.] cirsty widden was at Instar [Innister] 20 day before I rite yow this latter a fine littele Markes.

So dear and loving bother your sistar Elisa [&] brother send thir cind love to yow and hopes that yow will sike the lard ware ever yow gow as he is to be found in all place[.] rembar ashes [Zacchaeus] when he was found clim up the sishomery [sycamore] tree sicking [seeking] Jasus and hopes that yow will Make the rote [root] of a tre your closet[.] dear brother my earnes prayer is for yow and I hope yow would pray for me so that if we niver Mate on earth we Miht all Mite at our father right hand[.] so bloveing brother I am gone to klose this latter now with a few wards[.] your Mother is but tendar and very lonsom for yow alway and hopes that yow will come home at the eand of your contrake if the lord spares yow to serv the time

So loving brother yow will rembar your Mother And brother and sistars

Til dith

John Mowat

————————

After being promoted to steward at the Vancouver depot in 1854, Hugh Mouat was still at Fort Vancouver receiving wages in 1860, far from his “tendar and very lonsom” mother.