The Kirks and Kirkyards of Rousay, Egilshay and Veira – Part 4

by

Tommy Gibson

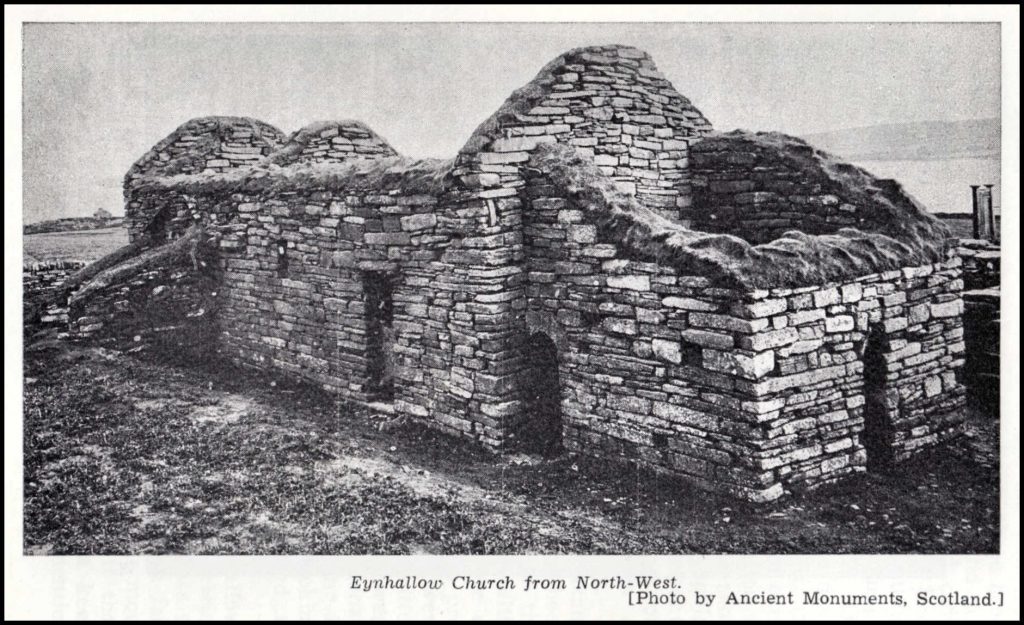

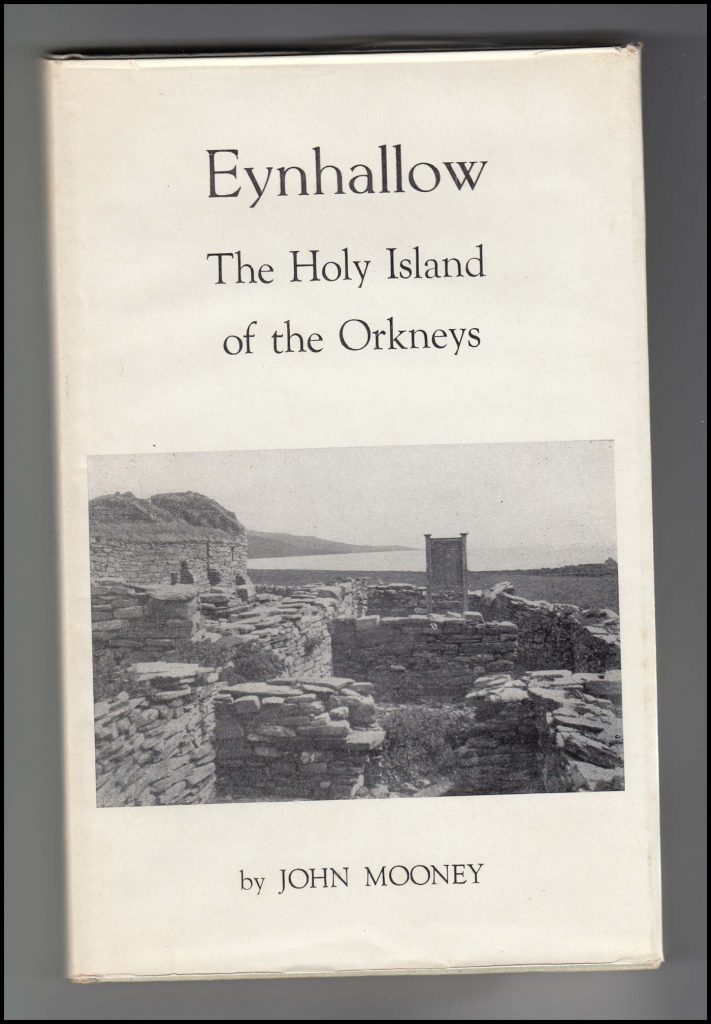

On Eynhallow there is a Monastery. A very famous monastery that dates back to the twelfth century. Much is written about the Island and its Church. John Mooney who wrote “Eynhallow, The Holy Island of the Orkneys”. Mr. Mooney certainly did a lot of research on Eynhallow, but a lot of it is conjecture. This book goes mostly over ordinary folks head. Having read the book several times I still do not fully understand it. Eynhallow was evacuated in c1853-4 for various reasons.

One of the reasons for the evictions was that the people on Eynhallow believed that the water was poisonous through the daytime but at night the water was all right to drink. Water beetles locally known as ‘clocks’ could not live in the wells in Eynhallow. (The problem being, that there was a midden above the well). Some of the Eynhallow folk were buried in the Westside Kirkyard, although Evie was the preferred Kirkyard by many of the families, although there are not any headstones erected to them. When a death occurred on Eynhallow, the body was placed in a boat and towed across to either Rousay or Evie. The people were very superstitious and would not travel in a small boat with a body. This must have been awkward in the wintertime if gales were imminent and a swell on.

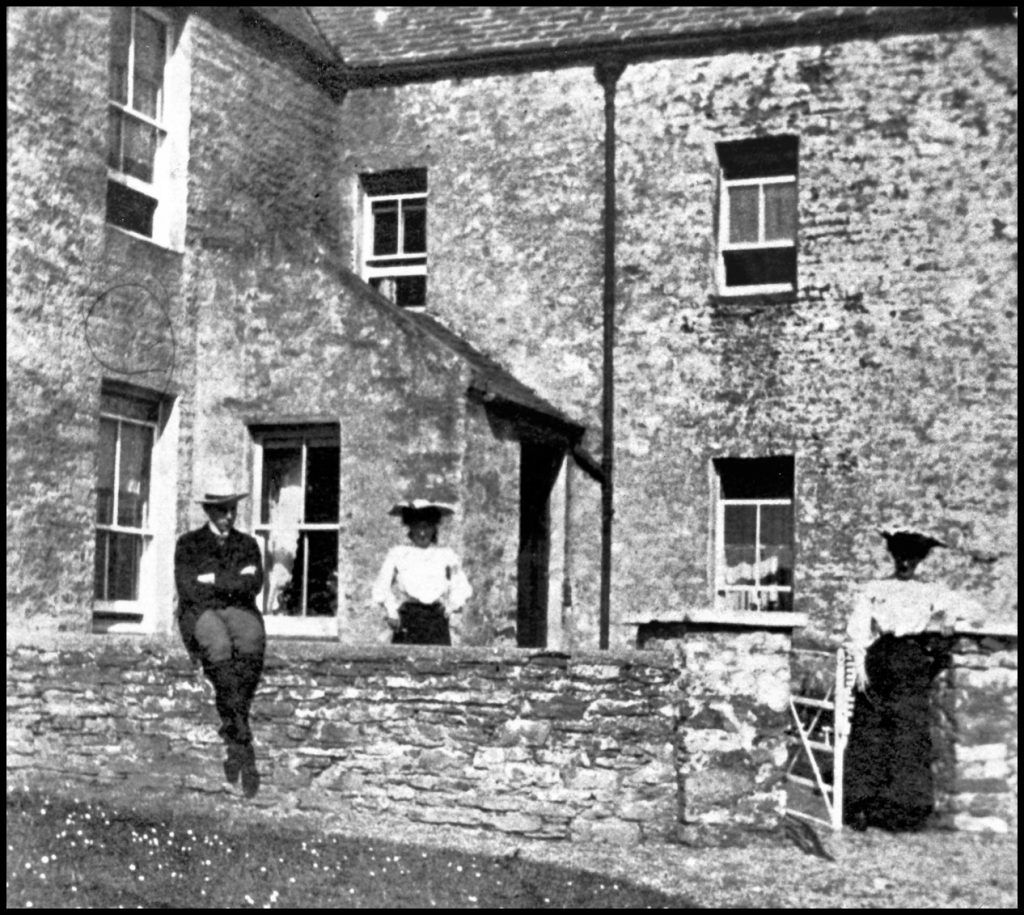

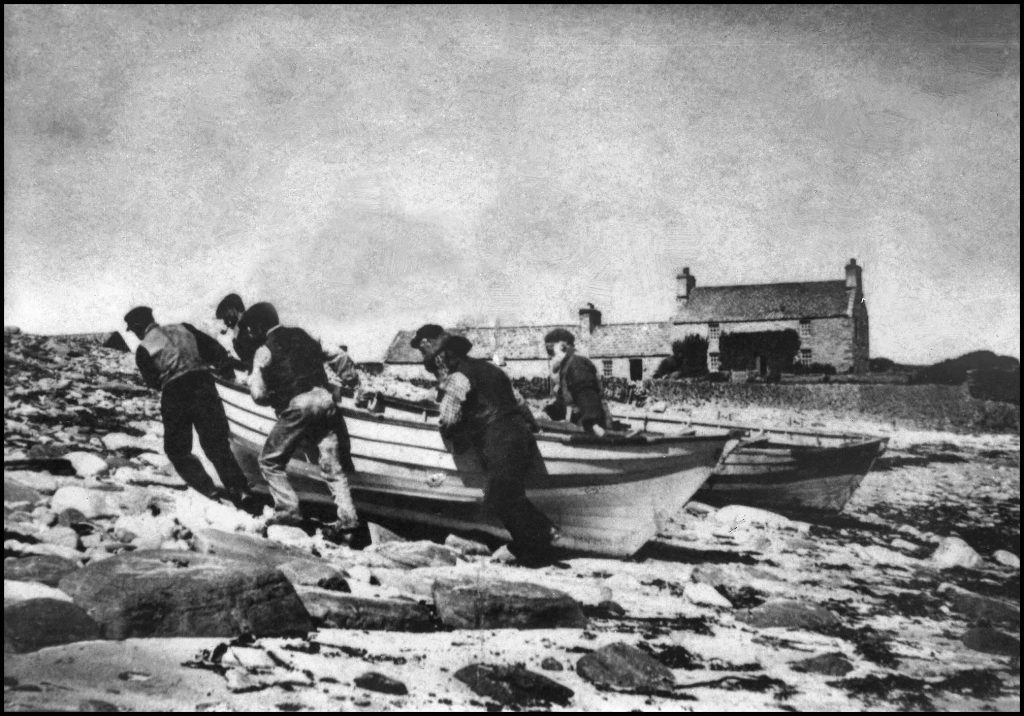

Below the Lodge is the most suitable place on Eynhallow to launch a boat but swell comes around even there and hampers boat work. Eynhallow is one of the most interesting of all the Orkney Islands. The lodge, a wooden building, built about 1860 was added on later by Thomas Middlemore, Westness House. This building, I believe, was built in case a shipwreck took place on Eynhallow. There was supposed to be provisions in the building, this would have been shelter in case of survivors. I was in the lodge a year or two back and it is a most interesting building in its own right. The furniture is now antique, but nothing fancy. Orkney Islands Council now owns the Island.

In the mid 1980’s Charlie Wilkinson who resided at Breck built a small Roman Catholic Church in what was an implement shed. Outside there is no indication that the shed contains a Chapel, but inside it is lovely. It seats around 20. The windows on the south end looks across at St. Magnus Church in Egilshay.

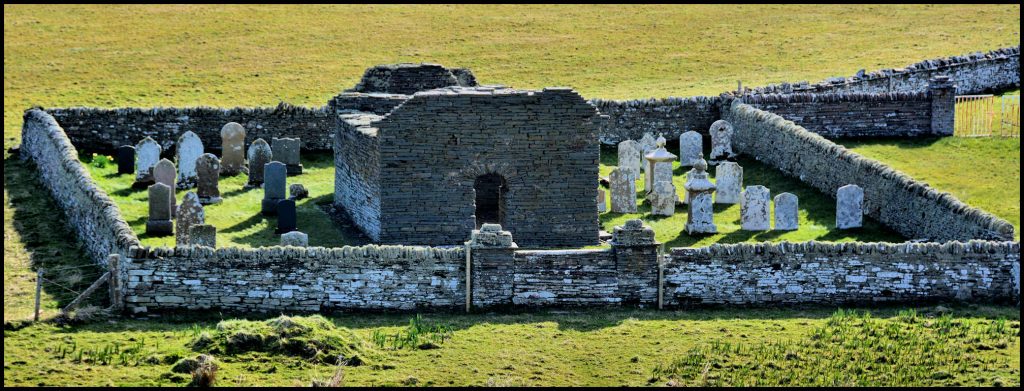

The Egilshay Kirk was built on a prominent part of the Island, but not the highest point. This would make it one of the oldest and most famous places of worship in Scotland. Some authorities consider to have been built before the advent of the Norsemen in 876. The present building was probably built around 1115. Its construction is unique to Orkney, with a tower built to a height of 63 feet. Local tradition says that the tower was once struck by lightning and this knocked it down by 20 feet. It was closed for worship about 1805 due to the state of repair of the roof. Some of the timbers were in a bad state of decay with no money to repair the roof. The slates from the roof were removed and taken down to the point of Vaardy where it was to go on the Store House, but this was never done. Many years later the roof was transported to the other side of the island to Meaness and put on one of the buildings, and is probably still there. The best of the timbers (couples) were cut into fencing stabs and used at Vaardy.

This unique Kirk is still a strong construction and is looked after by Historic Scotland. It is not known when the kirkyard dyke was built. The construction of the dyke is old but I suspect that it was built at a later date. If the stone in the wall was built over 800 years ago, the walls would not be as straight or in as good a condition as it is today without major repair or having been completely rebuilt at a later date. When the Kirkyard was built, the masons did not build a gate for access. To gain entry to the kirkyard was by stone steps built into the wall. Coffins were lifted and mourners had to climb over the wall. This practice must have been superstition about a body once in the kirkyard, it was in for evermore. There was no escape from the kirkyard through a gate.

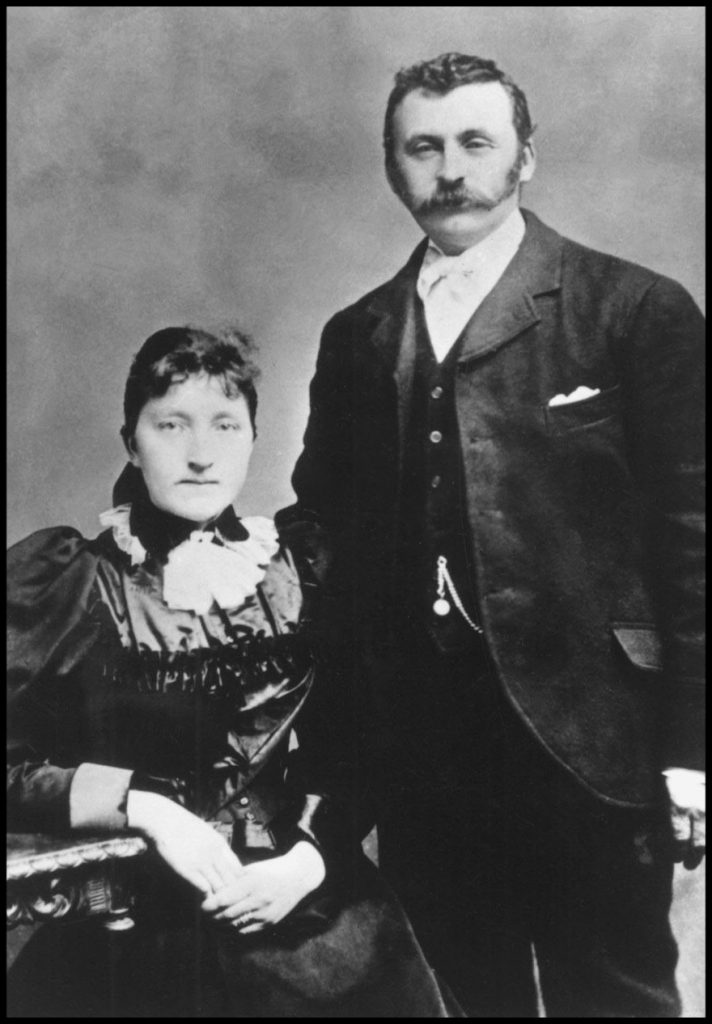

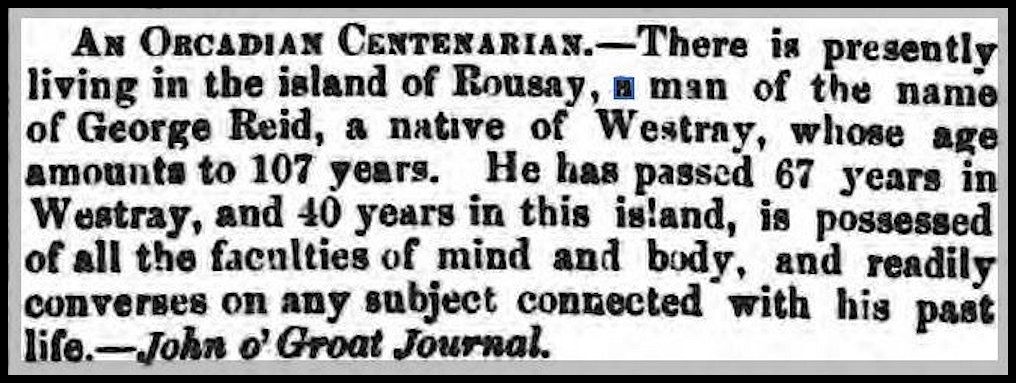

The 74 headstones in the kirkyard, which is 33 yards north and south by 41 yards east and west, are only at the east and south sides of the Kirk. This being the only burial ground, I believe this is the second or third time round. There must be untold hundreds of people buried here. The population of Egilshay in the 1841 census was 194. In earlier years in 1790 the population was 210, and in 1961 the population was down to 54. There are some graves inside the building but over the years the inscriptions have disappeared. The late Ernest Alexander of Kirbust, told me that my great-great-great-grandfather James Grieve, born in Egilshay in 1776, is buried in the Southeast corner of the Kirk. He was a navy pensioner. A stone is laid alongside but again no inscription; this may be his wife Elizabeth Davie. I often wonder why he was buried inside the Kirk? Who knows?? There is also a vertical stone laid near the door, but the inscription is not readable. The Laird of Egilshay, Robert Baikie MD, HEICS, of Tankerness died on the 5th August 1890 aged 98, and his wife Helen Elizabeth Davidson, who died on the 11th of January 1888 aged 72, are both buried under the small roofed section on the East end. That is five bodies we know of, but who knows how many more are buried inside?

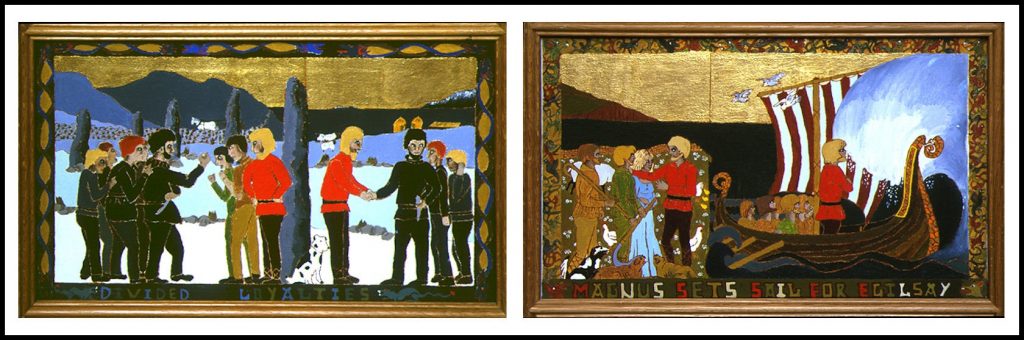

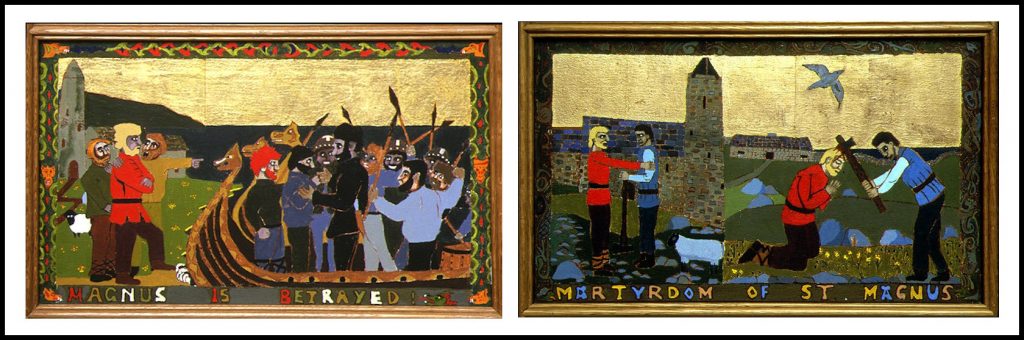

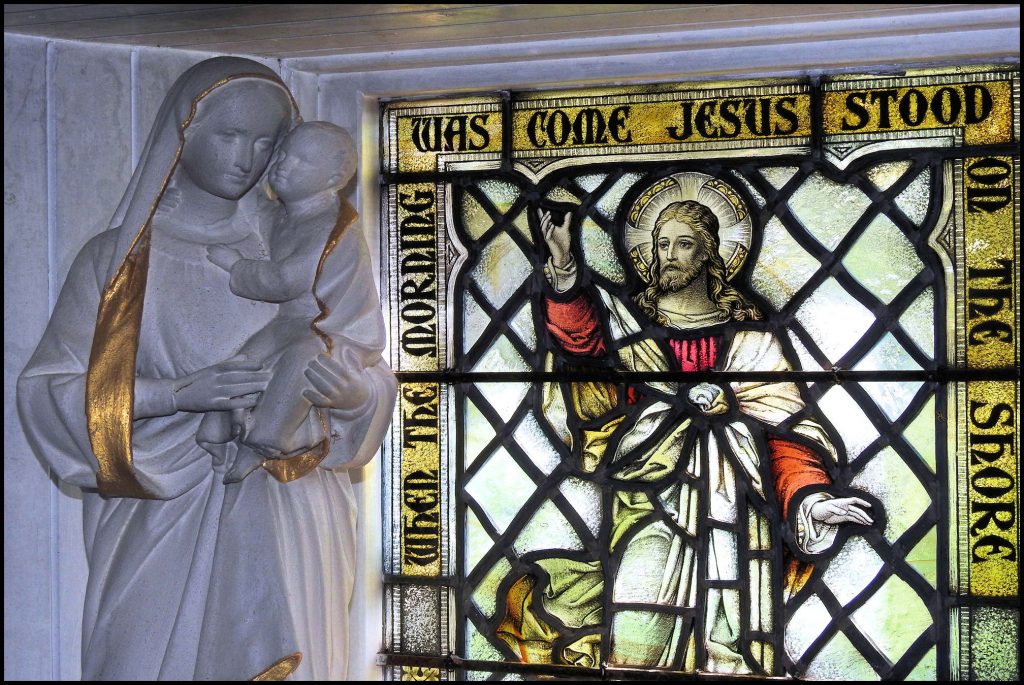

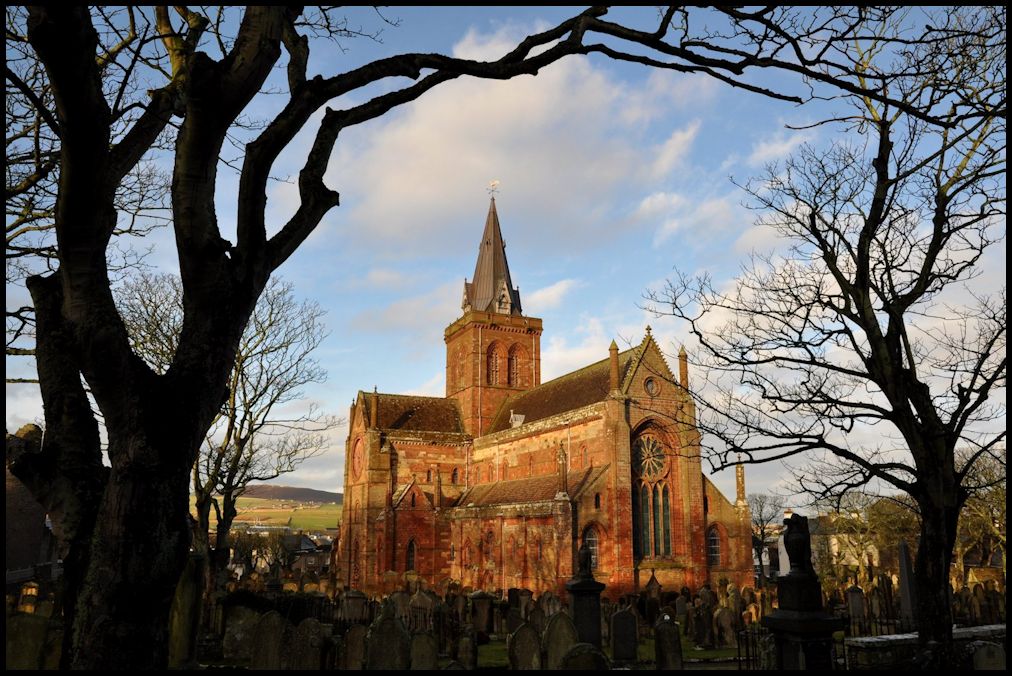

Mounted on the organ screen in the presbytery of St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall are a collection of panels depicting the events surrounding the martyrdom of St Magnus. The two above portray ‘Divided Loyalties’ and ‘Magnus setting sail for Egilsay’, whilst those below show ‘Magnus’s Betrayal’, and lastly his Martyrdom. The panels, painted by fifteen children from the Isle of Arran, were presented to the people of Orkney on June 10th 1980 as a tribute to the St Magnus Festival.

Magnus Erlendson, arguably the most famous of all the Norsemen who came across to this country, was murdered in Egilshay at Easter 1116. Many books have been written about this episode in history. In 1937 a memorial was built in his memory. This was financed by the London Church St. Magnus the Martyr. About a quarter of a mile to the south east of the church was a grassy mound. It was, says Egilshay tradition, the spot where St. Magnus was killed. A victim of the treachery of his cousin Haakon. Magnus, who was trying to escape, was running towards the shore to what now is Howan and the Knows to hide. Howan, the Lairds house, on the east shore, was first recorded in 1657. Hugh Robertson of Kirbust, who died in 1939 aged 92 was recorded saying that his father David who lived to be 95, died 1899, remembers that a large flat stone was sunk into the mound and mothers forbade their children to play there because on that mound blood had been shed. Since those days, however, the mound had been ploughed over and the stone removed. After that the mound had not been regarded with the awe as previously.

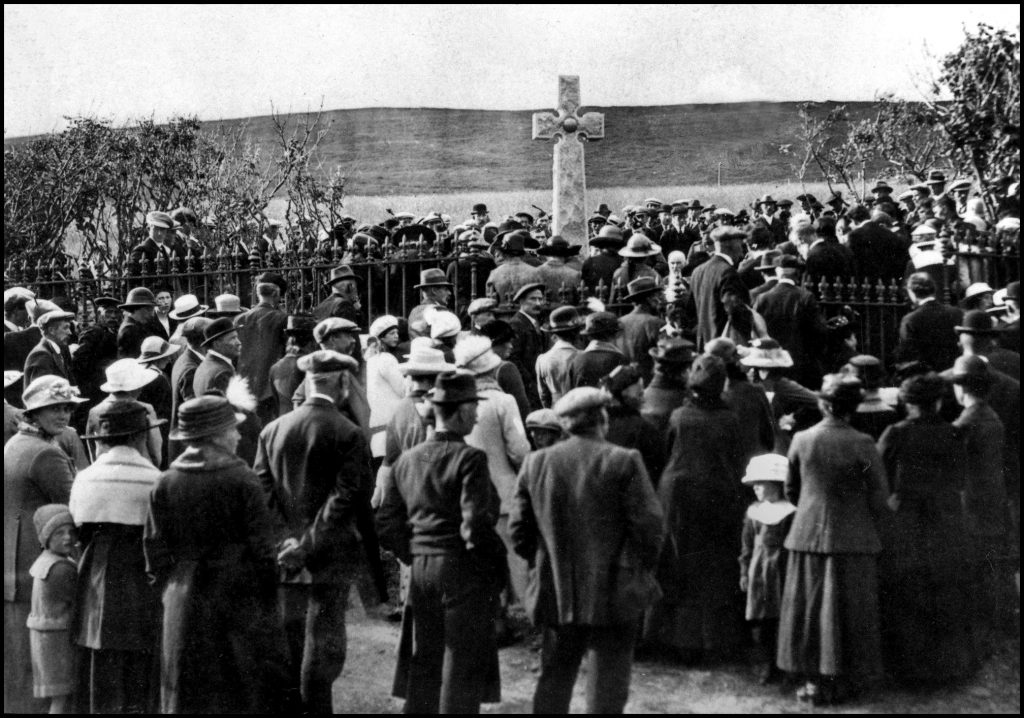

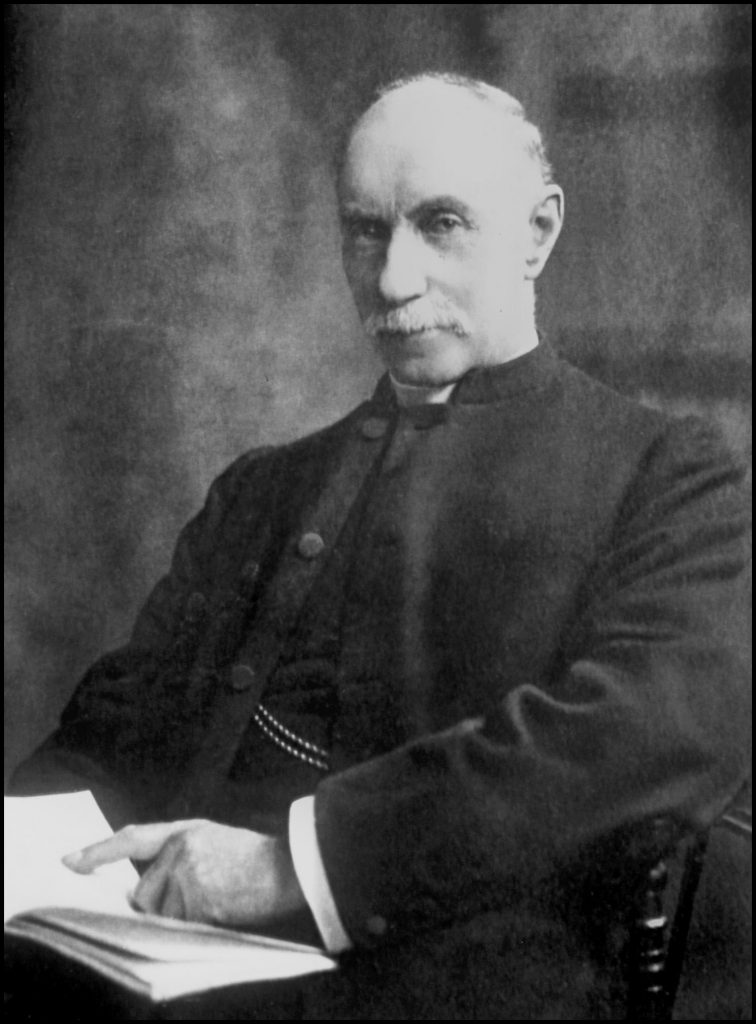

The Memorial was unveiled on the 7th of September 1938 by the Rev. G. Arthur Fryer M.A. BSc. from St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. The address was given by the Rev. H.F. Fynes-Clinton, Rector of the Church of St. Magnus the Martyr, by London Bridge. The Kirkwall town Band led the praise. Scripture reading was by Mr. David Turner, Lay Preacher, from Egilshay.

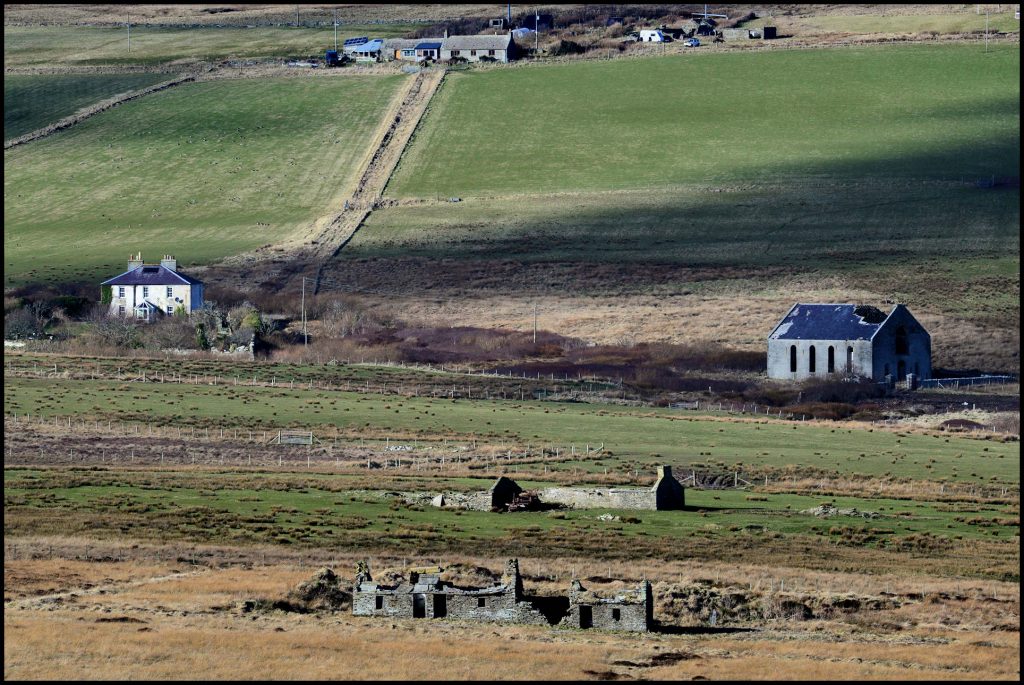

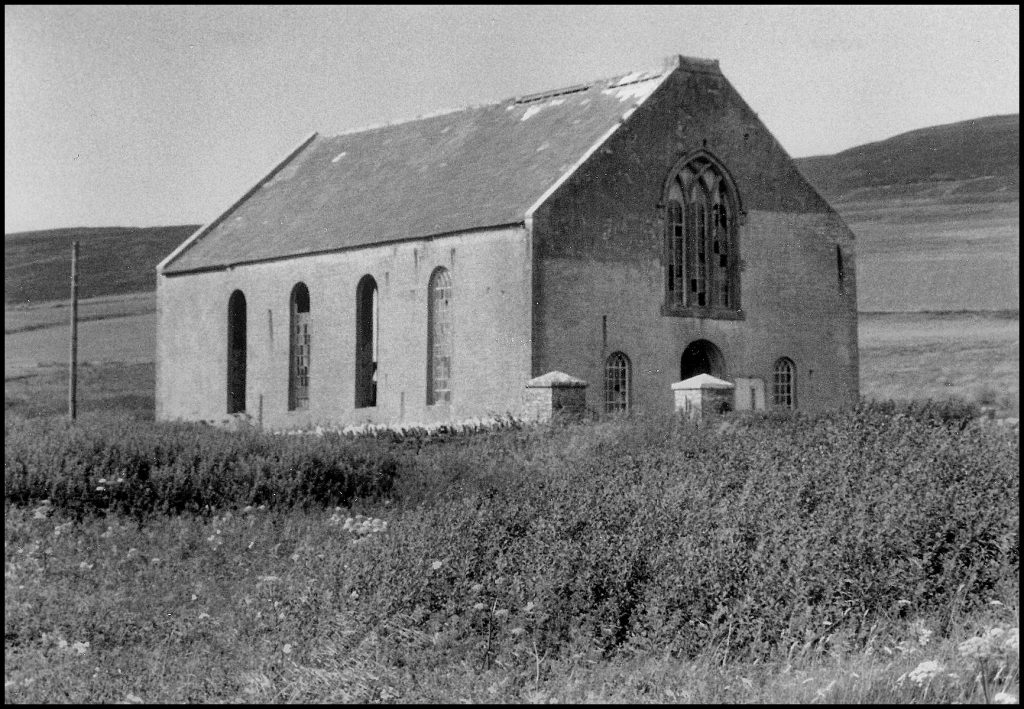

A new Kirk was built in Egilshay, 35 ft by 22ft with two arched windows at either side of the pulpit. Three windows each on the north and south walls, and a small window for the vestry. The door was on the south wall nearest the road. The Rev. David Webster opened the Kirk on the 18th of February 1885, with a large crowd in attendance. The manse was then erected in 1893.The first minister was The Rev. John Hendrie, former missionary in India and Trinidad. This Kirk was affiliated to the Paterson Kirk in Kirkwall and to the U.P. in Rousay. Ministers and Missionaries continued to live and work in Egilshay till the late 1930’s, Mr. Turner being the last. Of all the Kirks, I think that the Kirk in Egilshay was the nicest with the pulpit on the west end. A small vestry at the door, and a half-timbered ceiling. There is also a small War Memorial in the kirkyard for James Bews, Menis, who was killed in 1916, aged 20, and James Mainland of Weyland, who was killed on HMS Dasher, in the Clyde on 27.3.1944 aged 22.

St. Mary’s Kirk, Wyre, (some say it is St. Peters, or Peterkirk), nestles in a valley near the Bu, a warm tranquil area with a lot of wild birds. Close by is Cubbie Roo’s Castle. The building is the smallest of the old Kirks. Well built with strong walls, small windows, but the inside was plastered with a white lime to reflect the light. It is not known when the Wyre Kirk closed down but I suspect that it was about the same time as the St. Magnus in Egilshay. It was in a ruinous state in 1845.

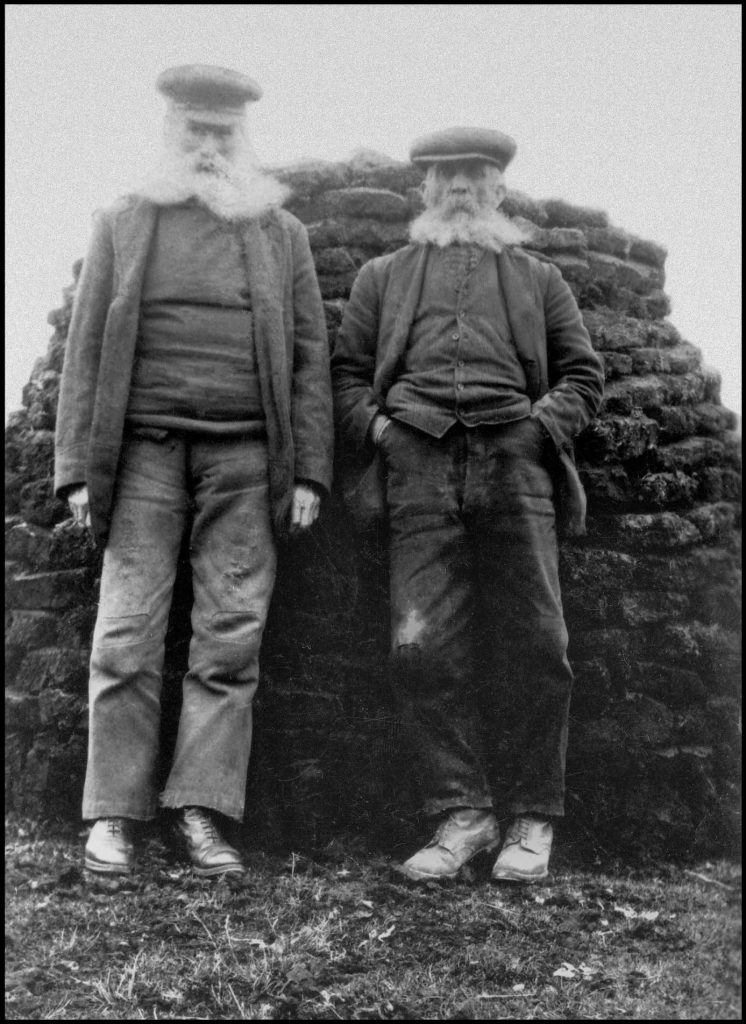

In the early 1930’s Cubbie Roo’s Castle [pictured above] and the interior of the Kirk was cleared of stones and Earth, clay, etc. The men dug down deep and came on some graves in which one was a large skeleton. This may have been Cubbie Roo or Kolbein Hruga. Cubbie Roo was supposed to have stood seven feet tall. All the bones and many artefacts etc from the Kirk and the castle was thrown in a small quarry close by. It is also known that most of the castle was taken down and the stones were used in the building of farm steadings nearby. No one knows what the castle looked like when it was in its splendour. The circumference may be known, but not the height. Very little of the castle remains. It is a pity that all that information is lost. Today when any site is excavated, every detail however small is recorded. 70 years ago very little was kept, if anything.

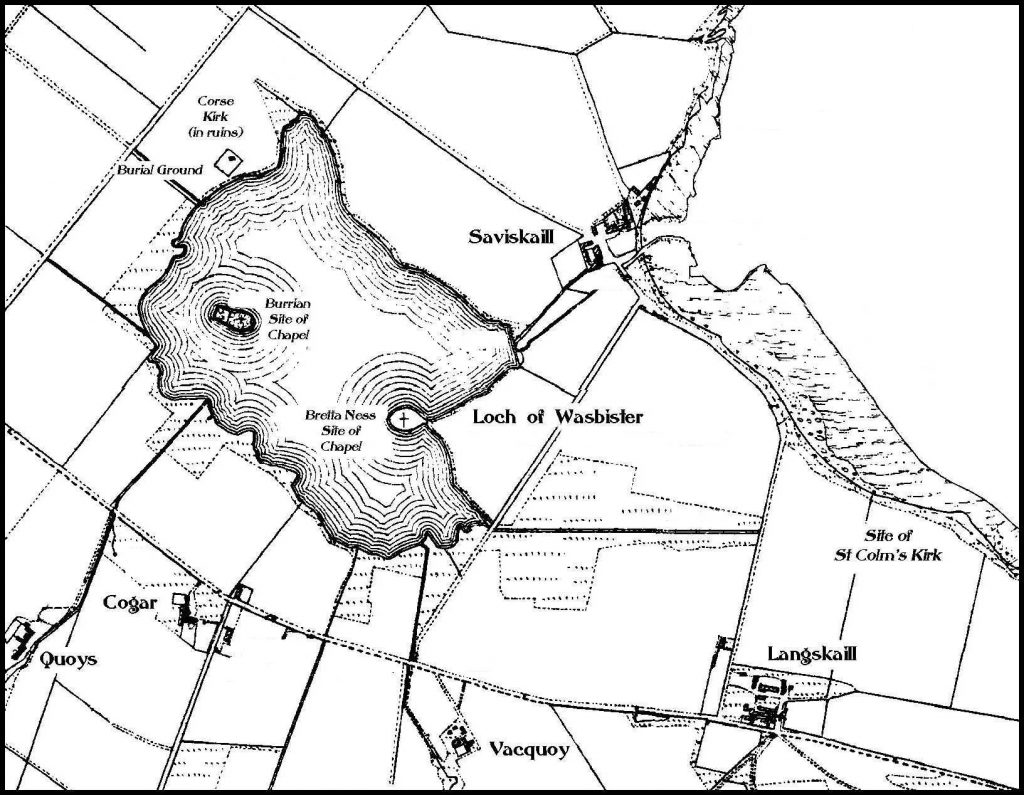

In 1790 the population of Wyre was 65, but in 1821 it went up to 80. In 1961 the population was down to 47, and now it is 15, which is too small for Wyre. In the old Kirkyard there are 48 headstones. A flat elevated tomb, (three in the Wasbister yard) was supposed to have appeared overnight. No one knows how or when it was built. Another interesting story is about a woman, Margaret Halcro, who “died” at Cavit. She was dressed in a shift and was laid out in the Kirk. The family tried to remove a ring from her finger, but failed. The undertaker also failed, so he took a knife to cut the finger. The first cut the woman woke up. (She may have been in a coma). The undertaker got a fright; the woman walked home to Cavit, and gave her family a bigger fright. She recovered. She left Wyre, got married, and her son built the “Kirk abune the Hill”, Birsay. The Kirkyard filled up and a small area was built on the South side. The first interment was in 1966.

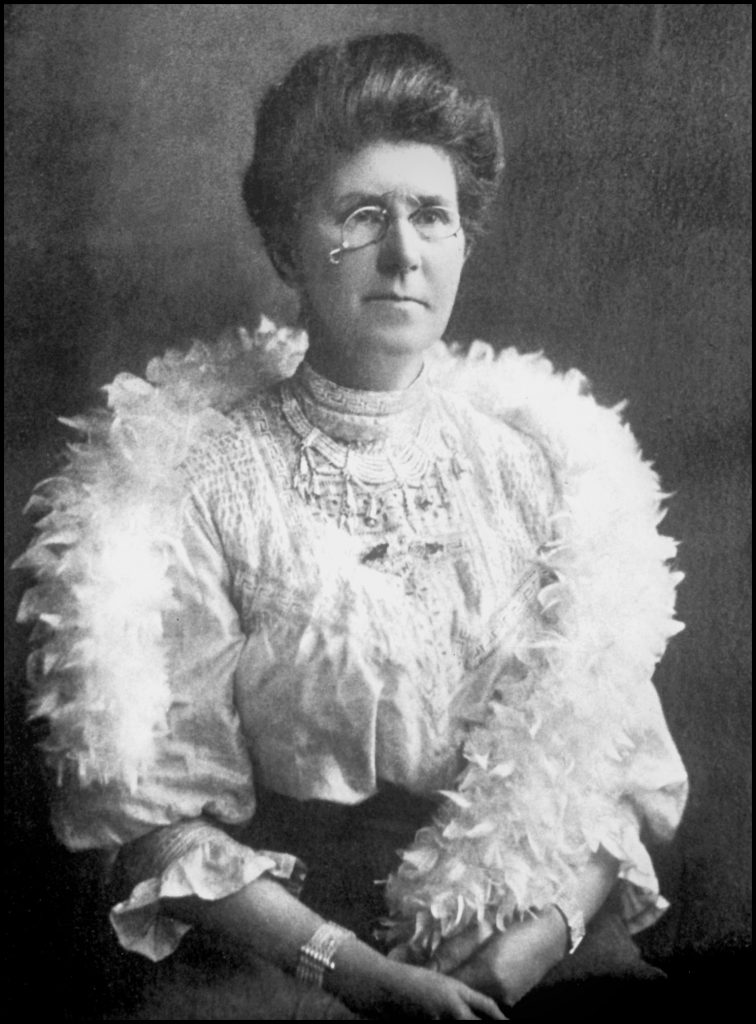

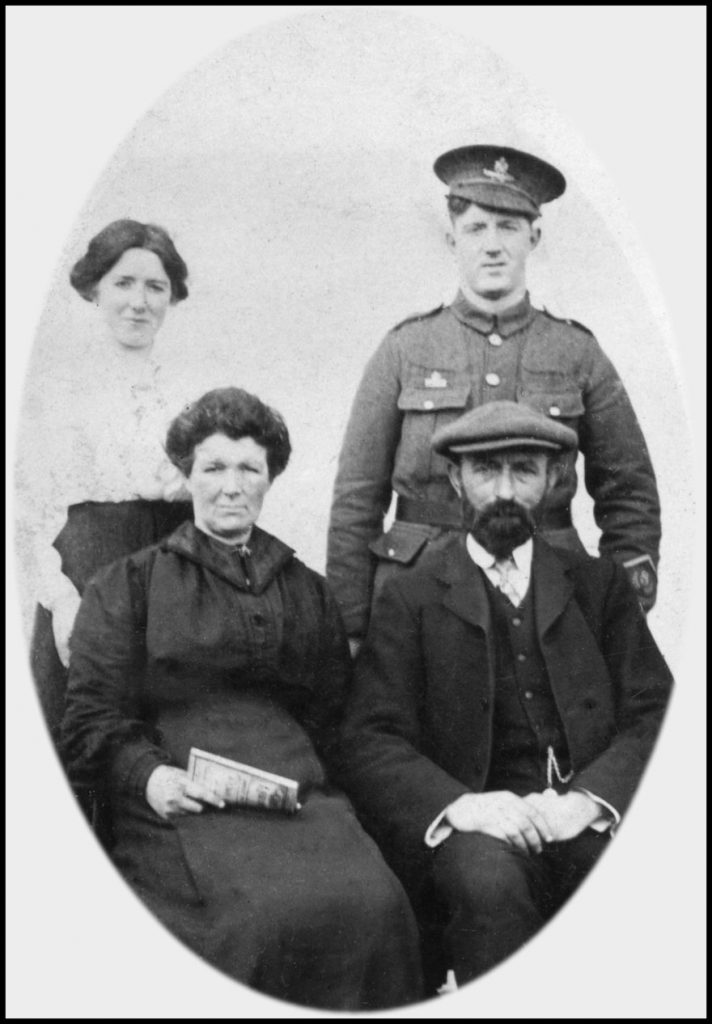

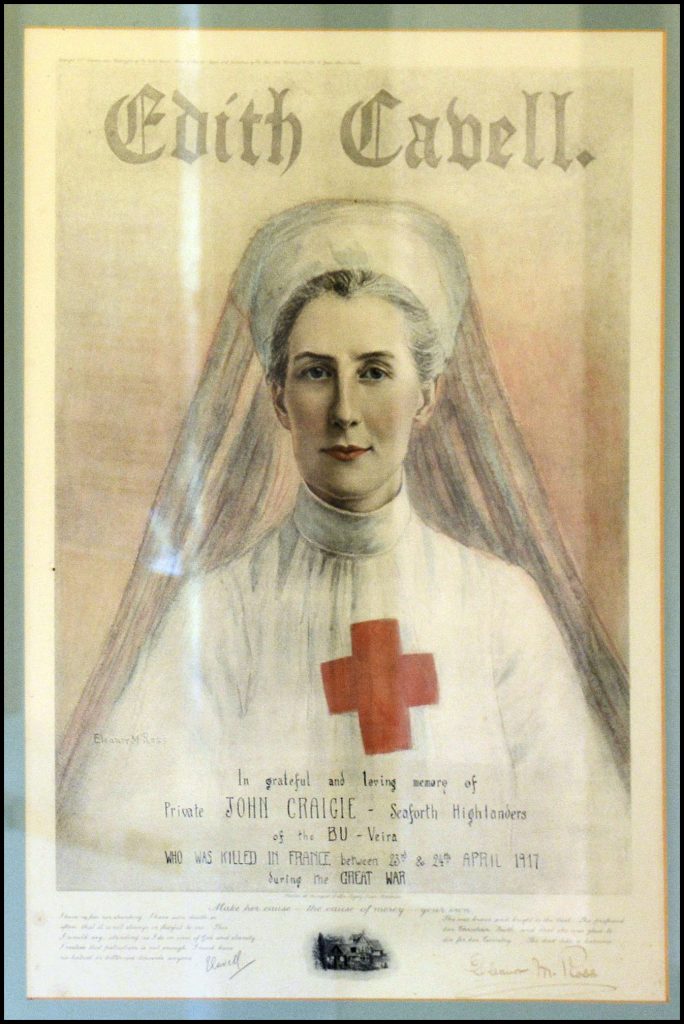

The Wyre War Memorial is a portrait of Edith Cavell by Eleanor M. Ross. The text was written by a Wyre schoolteacher. In grateful and loving memory of Private John Craigie – Seaforth Highlanders, of The Bu, Veira, who was killed in France between the 23rd & 24th April 1917 during the Great War. This painting hung in the Wyre School for many, many years. It is now in the Old Hall. I remember latterly, when the ministers went to Wyre, this was usually once a fortnight, took the services in the school or the old Community Centre. There was a small organ, which was used to accompany the hymn singing.

The Rousay War Memorial was unveiled on Sunday 3rd July 1921. The Service was in the U.P. Kirk; this was taken by The Rev. Pirie assisted by Mr. Shepherd from Egilshay. This was the largest ever congregation in the U.P. Kirk. Inside it was standing room only and a lot of people stood outside the door unable to get in. A total of 18 families in the parish were bereaved, and with a lot more men wounded, this was a very, very, sad occasion, which affected most of the parish. For WW2 three more names were added to the list, John S. Gibson, who was killed in France, Hullion; Thomas Walls, Store Cottage, Rousay, who died on the Burma Railway; James S. Mainland, Weyland, Egilshay, who was killed when his ship, HMS Dasher blew up on the Clyde.

Through the week all the ministers were good friends but on Sunday would not talk to each other. Each went about his duties on a Sunday, ignoring his colleagues.

Conclusion. The three main kirks in Rousay and the ones in Egilshay and Wyre are no longer in use. Some of the people don’t care, but a lot do. It is quite sad sight to see four good buildings go into a state of disrepair then to a ruin. These buildings used to be the heart of a community. Baptisement, christening, weddings and funerals were all linked to the Kirk. They were filled every week with four preachers giving their all. The wintertime Kirk Socials and Soirees filled the buildings with music. Teaching of music. Good music. All long gone, all in the past…..

© Tommy Gibson, Brinola, Rousay. 1996