TRAILS, TRAILL-BURROUGHS, MIDDLEMORE

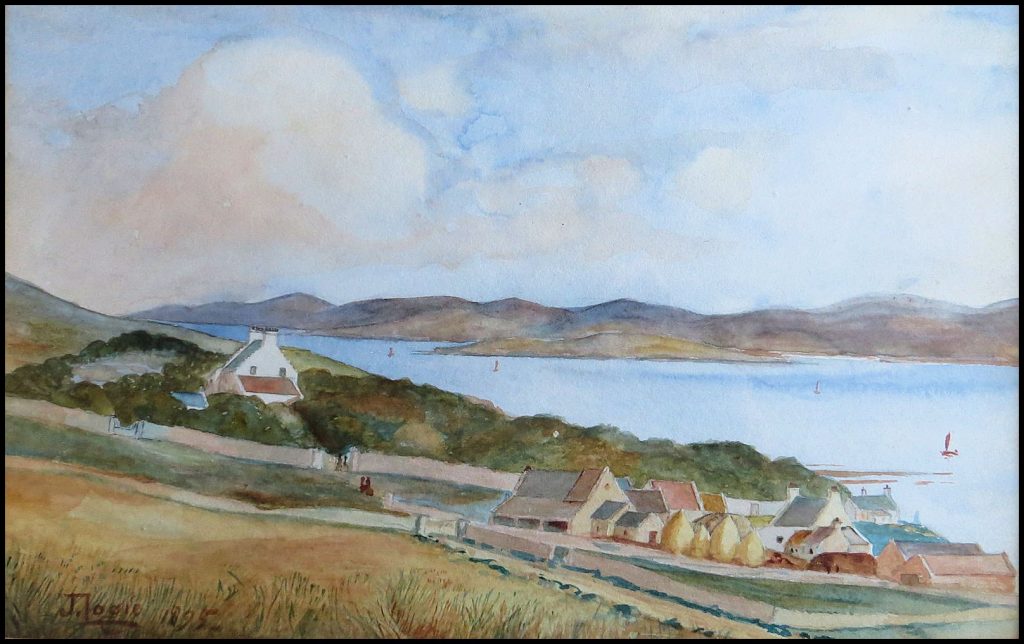

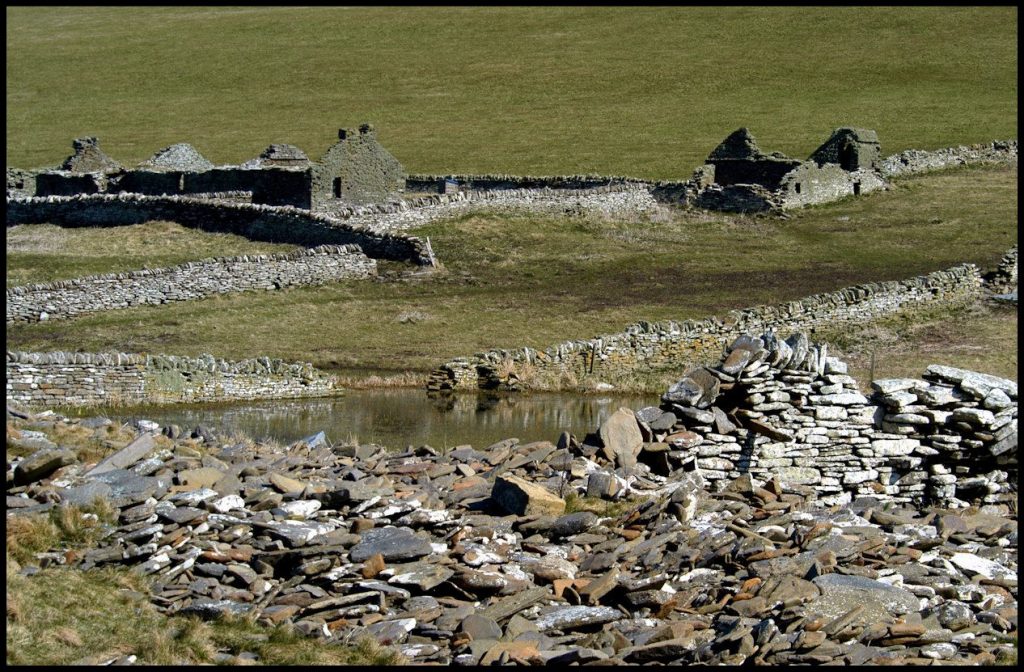

On the south-west side of Rousay, overlooking Eynhallow Sound from its sheltered position in a little copse of wind-blown trees, is the old mansion house of Westness. The shore below it – or somewhere not far away – was the scene of that dramatic kidnapping at which Sweyn Asleifsson simplified a political scene of some complexity by kidnapping the ruling Earl, Paul the Silent.

Westness was for a long time the home of a branch of the Traill family who first came to Orkney as followers of Earl Patrick Stewart, and they lived to proliferate, prosper, and dominate much of the islands’ life and commerce. They were a Fife family, originally the Traills of Blebo descended from an Archbishop of St. Andrews. The date when they acquired Westness is not known but George Traill appeared as a member of assize in 1615, and was described as ‘of Westnes.’

The dominant figure for much of the 18th century was John Traill. As a young man he had, like other Orkney lairds, flirted with Jacobitism, and in later years his 6ft 6ins frame was bent with rheumatism, which he attributed to the time he spent hiding in the Gentleman’s Cave in Westray.

In the aftermath of the ’45 rebellion Westness was one of those houses plundered by Benjamin Moodie of Melsetter who harried the Jacobites in the North Isles in a rampage of Hanoverian zeal. Moodie’s marines burned down both house and outbuildings and the present Westness House, built by John Firth in the summer of 1792, is its replacement. John Traill lived for fifty years after the rebellion, and when he died in 1795 he had long outlived his Jacobite past.

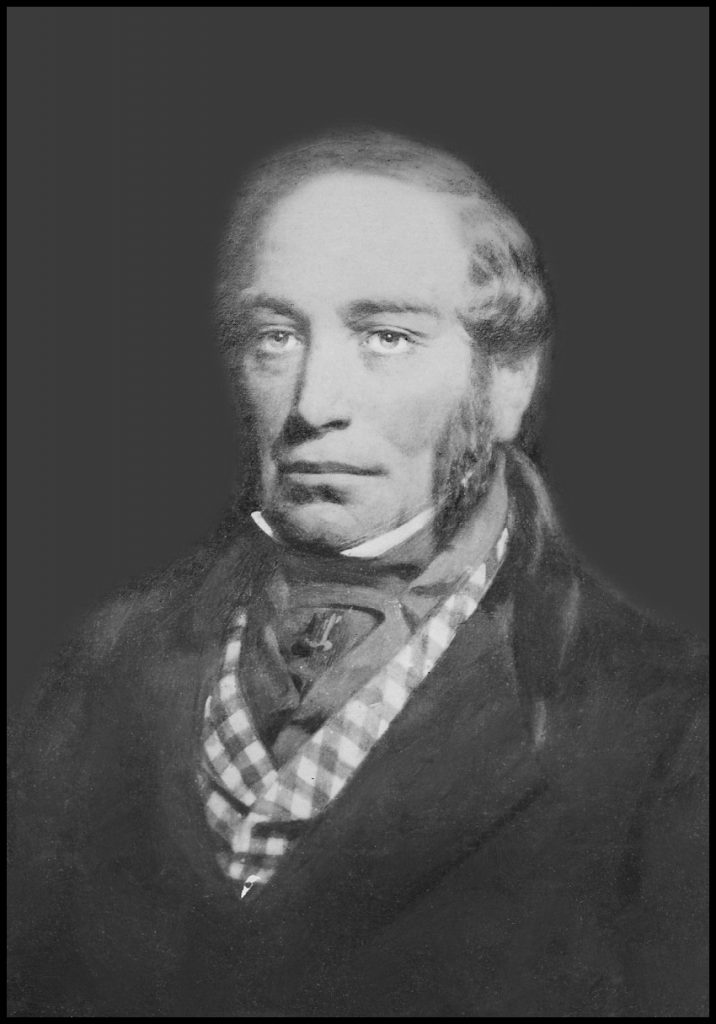

George William Traill retired from Army service in India and used his wealth to buy property in Rousay as it came on the market. His first purchase was the small estate owned by the Traills of Frotoft. Thomas Traill and his son William were only remotely related either to George William Traill or to the Traills of Westness. Their land consisted of the 6½ pennylands of Banks, Frotoft, a little property, which had existed intact at least from the 15th century.

These Traills were good examples of landowners in the merchant-laird tradition, the older style of Orcadian proprietor which people like Traill and Burroughs were superseding, thanks to their Empire careers and independent income. The fate of these Traills of Frotoft also illustrates the ruin and bankruptcy caused by the collapse of kelp prices.

Originally Thomas Traill was involved with his son-in-law William Watt of Sandwick in business ventures. Their enterprises included shipping joint cargoes of kelp to Newcastle, Dumbarton and other kelp ports aboard Traill’s ships. Return shipments of glass, slates, grain and general cargoes were disposed of through Watt’s extensive retail business.

Thomas’s son William ran into serious financial difficulties when kelp failed, and in December 1832 the estate was put into the hands of trustees. The bulk of the Traill property on the Mainland was sold in 1835 by the trustees, but kept Banks for a further five years, when it was sold to George William Traill. In 1850, William Traill’s debts were finally paid off, but by that time a new kind of laird was firmly established in Rousay.

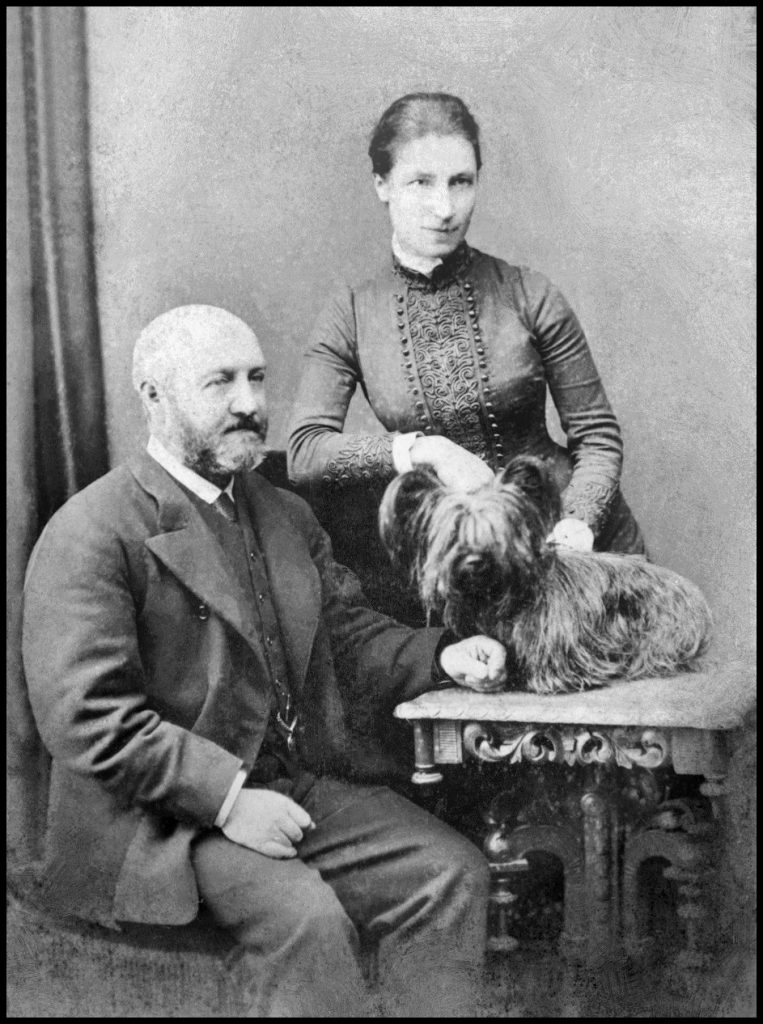

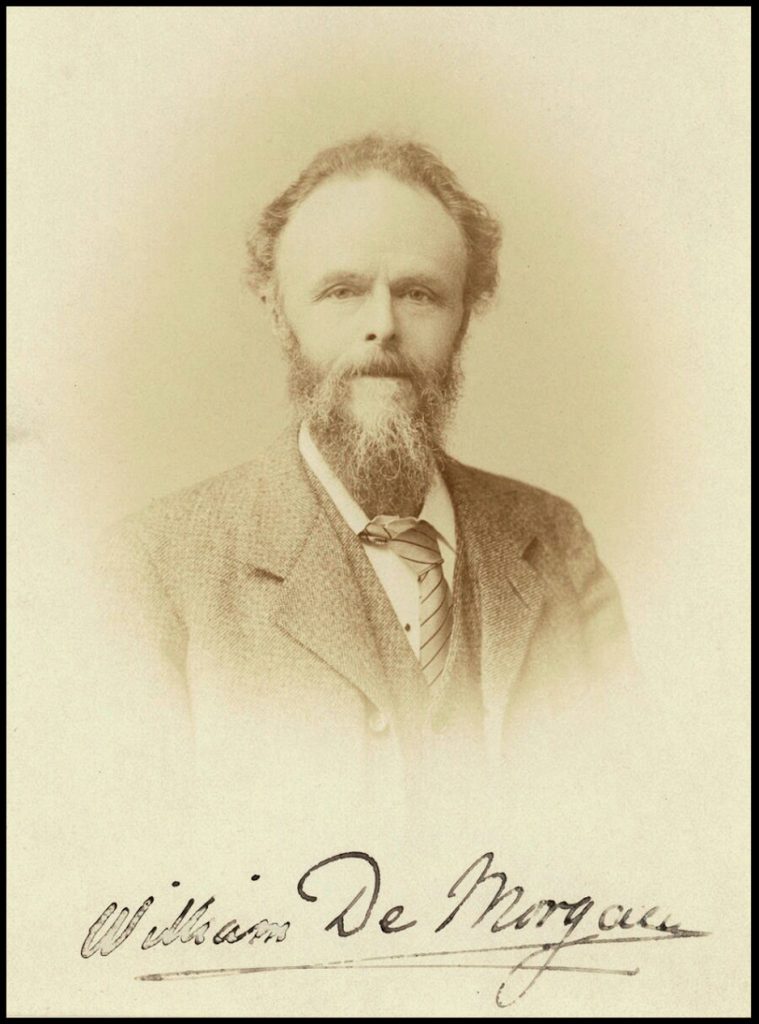

George William Traill, pictured to the right, was to be remembered as the tyrannical laird of Rousay who effected the most thoroughgoing clearance to take place on any Orkney estate. His ultimate achievement was the purchase of the lands of Westness in 1845 (but not Westness house). He looked on his acquisition of the ancestral lands as a mark of success, but it was a success which he did not enjoy for long. In November 1847, at the age of 54, he died in London as a result of a heart attack.

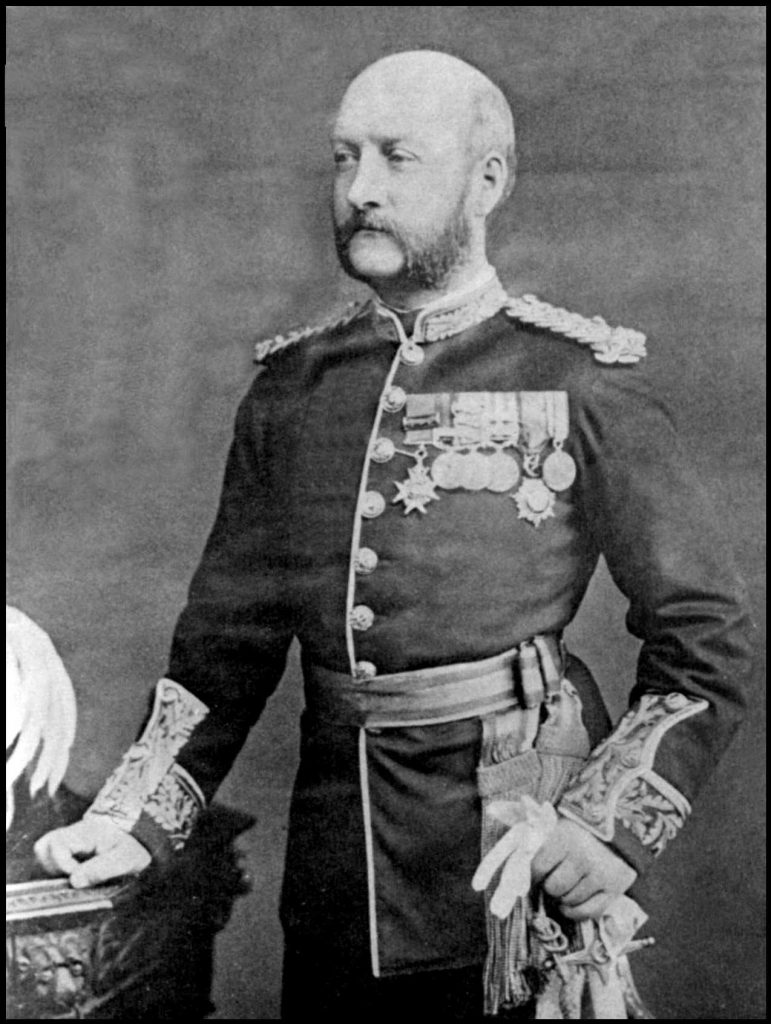

It is at this point the first mention of Frederick William Burroughs is made. He was born on February 1st 1831, and after education at Kensington grammar school, at Blackheath proprietary school, and in Switzerland, Burroughs was gazetted ensign in the 93rd Highlanders on 31 March 1848. Promoted lieutenant on 23rd Sept. 1851, he became captain on 10 Nov. 1854 and major on 20 July 1858. On his twenty-first birthday (1 Feb. 1852) Burroughs succeeded to the estates of his grand-uncle, George William Traill of Rousay and Viera, and assumed the surname of Traill-Burroughs.

James Irvine Robertson was Sheriff Substitute of Orkney and kept a journal. His entry for Wednesday 12 July 1848, reads as follows:-

John Baikie called in the evening and told that Burrows [sic] the young Laird of Veira is arrived (a dwarf of 18 or 19); and to ask me to read the funeral service at a sailor’s funeral tomorrow. I suggested that he should do it himself, but he pleaded that the world did not regard him as a praying man; and we agreed to get a presbyterian Clergyman to officiate.

Three days later their paths crossed again:-

Saturday 15 July 1848. Went out to Birstane before breakfast at half past 8, and from thence accompanied Wm Balfour and Calder in Trenabie’s Yacht to Elwick where we breakfasted. After breakfast Mr Burrowes the nephew and heir of the late Mr George Wm Traill of Veira came to Elwick in a boat from Kirkwall and Wm Balfour introduced him to us all. He is about 18 years of age and 5 feet or thereby in height; a very little man, but Gentlemanlike and extremely good humoured. We sallied out for Balfour to see the new house; it is really a beautiful and handsome building, but whether from its height and exposed situation it will not look bare and naked owing to the total want of trees is another thing. Walked over the farm and through the long park, Mr Burrowes having first left for Rousay, and dined at half past 3.

The Rousay census of 1851 gives the following information relating to the occupants of Westness House. 54-year-old William Traill, a Justice of the Peace born in Kirkwall, was head of the household. His second wife, Henrietta Moodie Heddle, was 36 years of age, and she was born in Walls, Hoy.

At this time William Traill had a family of seven children; the two from his previous marriage were Harriet (30) and Ellen (22). The others were Robert Henry (10), Henrietta (7), Eliza Williamina (5), Frederick (2), and a 3-month-old infant christened Walter.

Traill employed five house servants, all of whom were unmarried; Isabella Marwick (40), Betsy Louttit (34), Janet Marwick (30), Elizabeth Halcro (20), and Mary Marwick Gibson (20).

When George William Traill acquired Westness, it was the land only which he bought. Westness House remained the property of William Traill. He died in 1858, and in 1863 when Mrs. Traill died Frederick William Traill-Burroughs was able to buy the house, although financially embarrassed at the time, and he set about the work of renovation.

From the columns of the John o’ Groat Journal, November 17th 1859

ENTERTAINMENTS ON MAJOR BURROUGHS’ ESTATE. – On Tuesday the 11th ult., Major Burroughs of Rousay and Viera, entertained his tenantry to dinner in Westness House, Rousay. Mr Scarth of Binscarth was also present. The entertainment was all that could be desired. A number of loyal and patriotic toasts were given, and ably supported by suitable addresses, in which the several speakers among the tenants eulogised their worthy landlord, and his go-ahead factor. The utmost good feeling prevailed, and evidence was abundant that the best understanding prevails between the gallant Major and his tenantry. There were upwards of 60 present. In the evening, pursuant to arrangement, an excellent supper was provided for the youth on the estate, who attended in large numbers, of both sexes, and enjoyed themselves to their hearts’ content till a late, or rather an early, hour.

1862 June 17th – Orkney Herald

Important Sale of Household Furniture

There will be Sold, by Public Auction, at the HOUSE OF WESTNESS,

ROUSAY, on WEDNESDAY, the 2nd July,

A QUANTITY of Excellent HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE, comprising Dining-room Tables and Chairs; Drawing-room Table and Chairs; several very handsome Book-Cases; a Piano; Sofa; Opera and Four-post Bedsteads, and a quantity of first-rate Bedding, Pillows, and Mattresses; Iron Bedsteads; several first-rate Chests of Drawers; Dressing Glasses and Tables; Wardrobes; Carpets; Rugs; Bed and Table Linen of the best quality; Blankets; Crockery and Kitchen Utensils; besides a variety of other articles. Also, a number of Geraniums, Roses, Myrtles, and other Plants in Pots.

A large Boat will leave Kirkwall on the morning of the day of the Sale, and a Boat will ply between Aikerness and Rousay, for the convenience of intending purchasers.

For further particulars apply to J. C. SCARTH, or to JAMES S. HEWISON, Auctioneer.

1870 September 28th – Orkney Herald

0n Thursday, the 22d instant, Colonel Burroughs entertained the tenantry of Rousay and Viera to dinner at Westness. The day was one of the finest of this fine season; but there was evidence of a severe gale in the far Atlantic in the fringe of white foaming waves, which stretched, in a line outside Eynhallow, from Skeaburgh Head to Costa, and the roaring surge in the caves of the West Crags. The sun shone brightly, and the inner sounds were smooth as a mirror, reflecting the hills and headlands. Westness, always beautiful, looked its best on this day, giving a smiling welcome to the groups of gaily dressed people, who were seen descending the hills and filing through the glens on their way to it.

The splendid weather made some change in the arrangements for dinner, for which the barns had been seated. It was resolved to dine outside upon the grassy lawn which extends from the garden wall to the burn at the offices. Never was seen a more beautiful sight anywhere than the party of about 400 old and young men and and women, seated in half circles upon the green slope, interspersed here and there with a group of beautiful girls, dressed in white muslins, with gay sashes and head dresses.

The Rev. Mr Gardner, minister of the parish, asked a blessing; and the Rev. Mr Rose, of the Free Church, returned thanks, each, in appropriate language, urging gratitude for the fine season, the bountiful harvest now secured, and the happy circumstances under which they were all met that day to enjoy the liberal hospitality of their landlord, who had returned to them after long and arduous labour in distant lands, and in the service of his Queen and country.

The dinner lasted from three to five o’clock, the bagpipes being played all the time, and thereafter the young people enjoyed themselves until sunset dancing on the green, while the elders and children had free access to the gardens; Colonel and Mrs Burroughs, and their friends, exerting themselves, and most successfully, to make all feel comfortable and to enjoy the day.

When the daylight «as about done, the barns were lighted up and tea served round, and with three violins and the bagpipes, dancing was kept up in the three barns with great spirit until eleven o’clock, when all said good-night and returned to their homes pleased with their day’s enjoyment, and highly appreciating the urbanity and frank kindness of Colonel Burroughs and of his amiable lady, who has gained all hearts in Rousay. No wonder that all the tenants are delighted with the near prospect of their taking up their permanent residence on the island. Soon may the time arrive when we shall have no absentee proprietors in Orkney.

We understand that Colonel Burroughs left for Thurso on Monday, on his way to Dunrobin Castle, having an invitation from the Duke of Sutherland to spend some days there. Afterwards he returns to his regiment, the 93rd Highlanders, now quartered at Aberdeen, his leave of absence not extending beyond the present month.

We cannot close this record of a happy day in Rousay without a reference to the admirable way in which the details were managed by Mr Learmonth, Colonel Burroughs’ overseer in Westness farm, and the preparation of the dinner by Mrs Learmonth, and the waiting by the servants No one was neglected in all this numerous assemblage, and although there was an abundant supply of beer, ale, and even of toddy, not a single case of anything approaching to intemperance occurred ; while the demeanour of old and young was highly creditable to the islanders, and most have been gratifying to their clergymen who were present.

The house was repaired and redecorated, the grounds were set to rights, greenhouses built and garden walls reconstructed. In 1872 the house was re-roofed and an extension was added. Being himself in India, Burroughs let the house with shooting and fishing rights over the whole of the estate. His tenant was yet another Traill, James C. Traill, a London lawyer who, although not closely related, was a friend from Burroughs’ schooldays at Blackheath.

Thereafter Westness was occupied rent-free by military acquaintances. While he himself was absent, Burroughs considered it more important to have a tenant he could trust rather than to maximise the profit from sporting rights. When he returned from India, he occupied Westness from 1870 to 1875, but, on the completion of his new mansion at Trumland, Westness was again let as a sporting property.

The letting was now on a more business-like basis. The Westness tenant had shooting rights over only half the island, the other half being reserved for the laird, and he was allowed to fish on alternate days on Muckle Water, Peerie Water, and the Loch of Wasbister. For these reduced rights, the shooting tenant paid a rent increased to £200 from the £50 it had been when James Traill was tenant. Burroughs felt it was worth much more. He reckoned that it cost him £50 a month to let the house and provide a gamekeeper, gardener, dogs, ponies, boats and boatmen. A rent of £1,360 for a six months’ lease would, he considered, be a more realistic figure. It was, however, much more than he was likely to be able to obtain.

In 1877 the house was let to Patrick Grant for £200, with shooting over half of Rousay and fishing. In 1879/80 John White paid £174 12s 0d, while in 1880/1 Thomas Brown paid £200, as did John Bell Irving in 1881/2, and Sir Arthur Halkett Bt. in 1882/3.

Perhaps the most colourful visitor to Westness House was Lady Florence Dixie, daughter of the 7th Marquess of Queensberry, who stayed at Westness with her husband in 1885. Born in 1857 she was a traveller and writer and in 1875 she married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie (Sir A.B.C.D. or ‘Beau’ for short). ‘Florrie’ was Field Correspondent of the London Morning Post in 1879 and was instrumental in securing the short-lived restoration of Cetshwayo, the Zulu king in 1883. She wore her hair short, commonly dressed in a sailor’s suit and was a regular speaker on Scottish nationalism and women’s rights. As an ardent champion of the underdog, her presence in Rousay at the height of the trouble between the laird and his crofters was potentially explosive. Lady Florence, however, was a keen sportswoman and a good shot. She appears to have been more intent on killing grouse than involving herself in local crofting politics during her stay on the island in 1885.

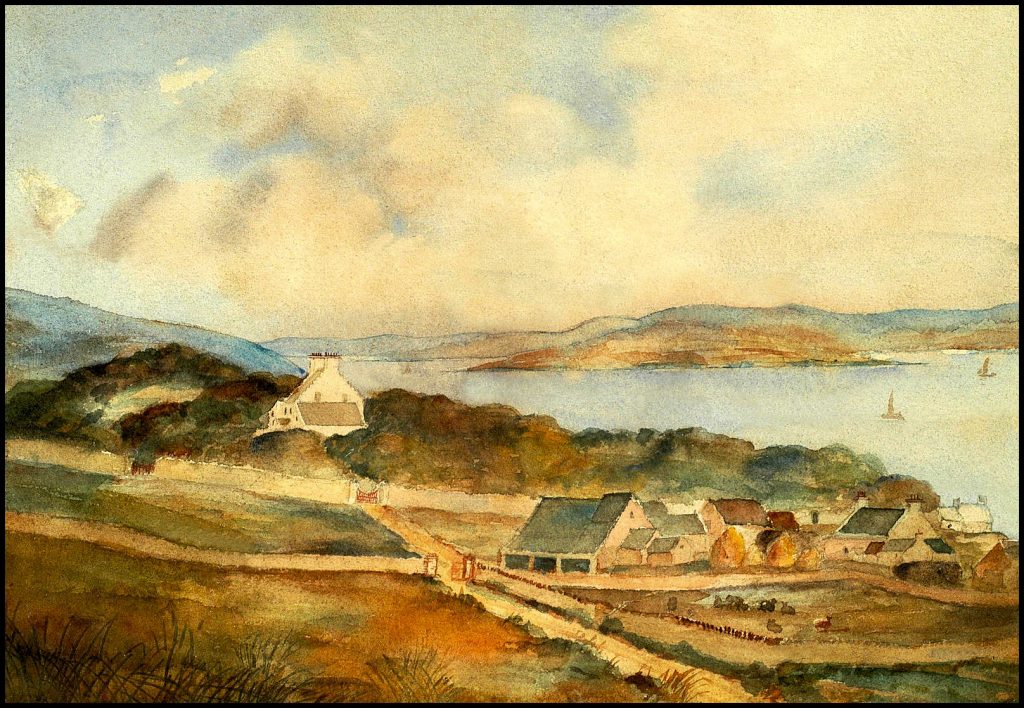

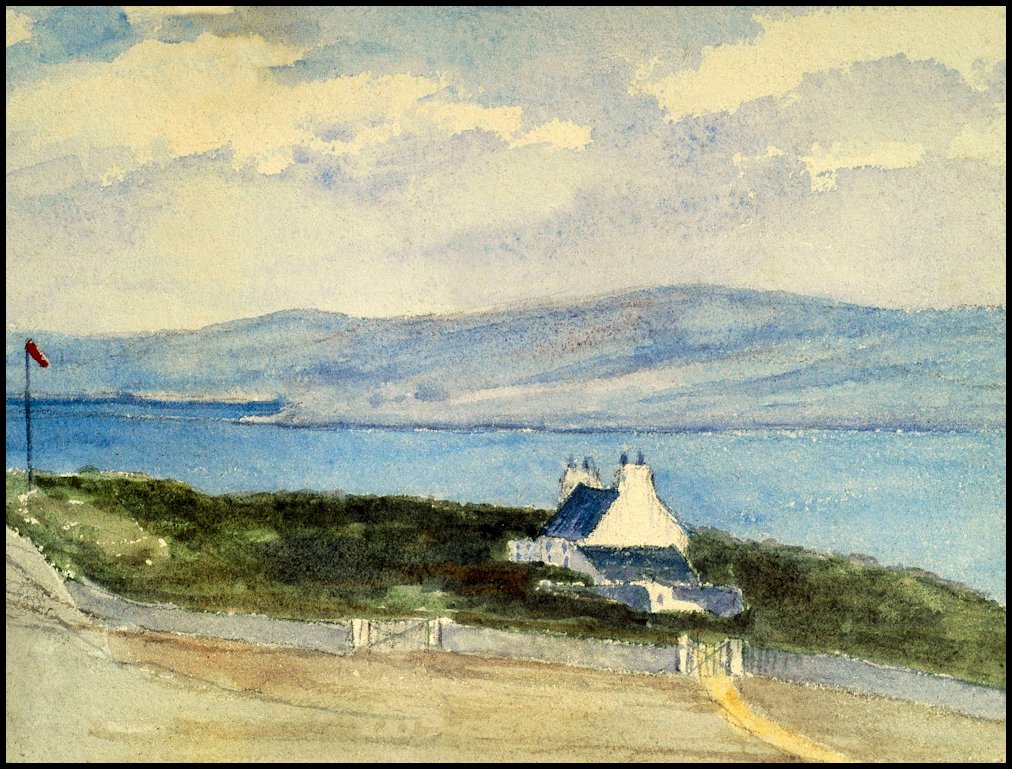

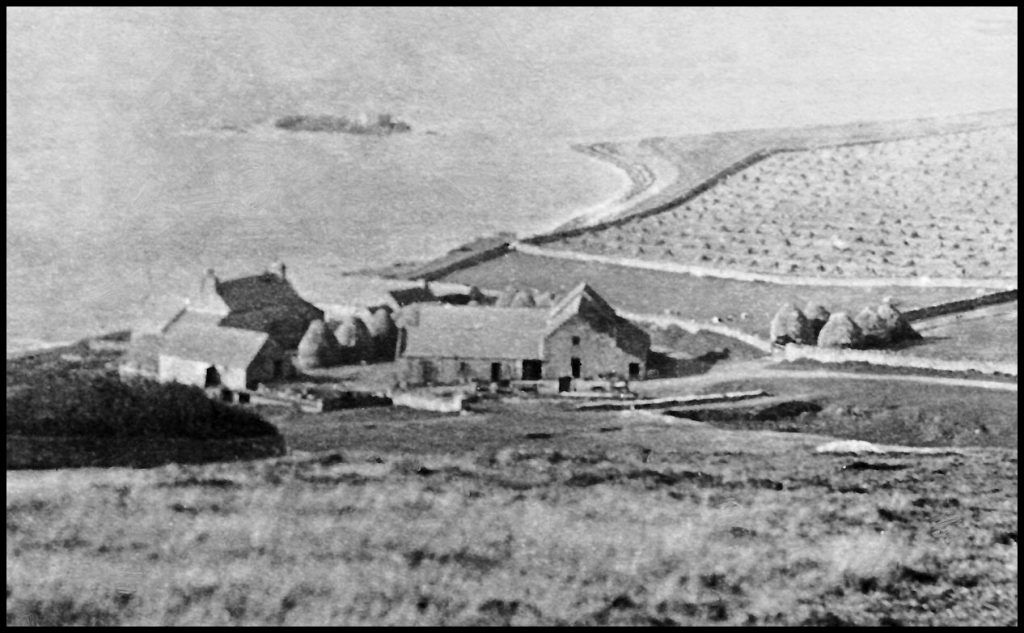

of this view of Westness from Evie.

In 1887 Colonel Macdonald (sub-let to Sir Price, Bt.) paid £100 for the privilege of staying at Westness House. In 1893 the tenancy was vacant despite “40 grouse from Yorkshire and Cumberland let out on the Rousay moors in November 1892”!

1893 August 18th – Dundee Courier

Lord and Lady Granville Gordon arrived at Kirkwall, per steamer St Clair, yesterday, shortly afterwards proceeding, per yacht, to Rousay. Lord Gordon has taken Westness House, Rousay, for the shooting season, but on the Rousay Moors this season grouse are to be protected. There are, however, plenty of snipe, plover, hare, rabbits, and ducks.

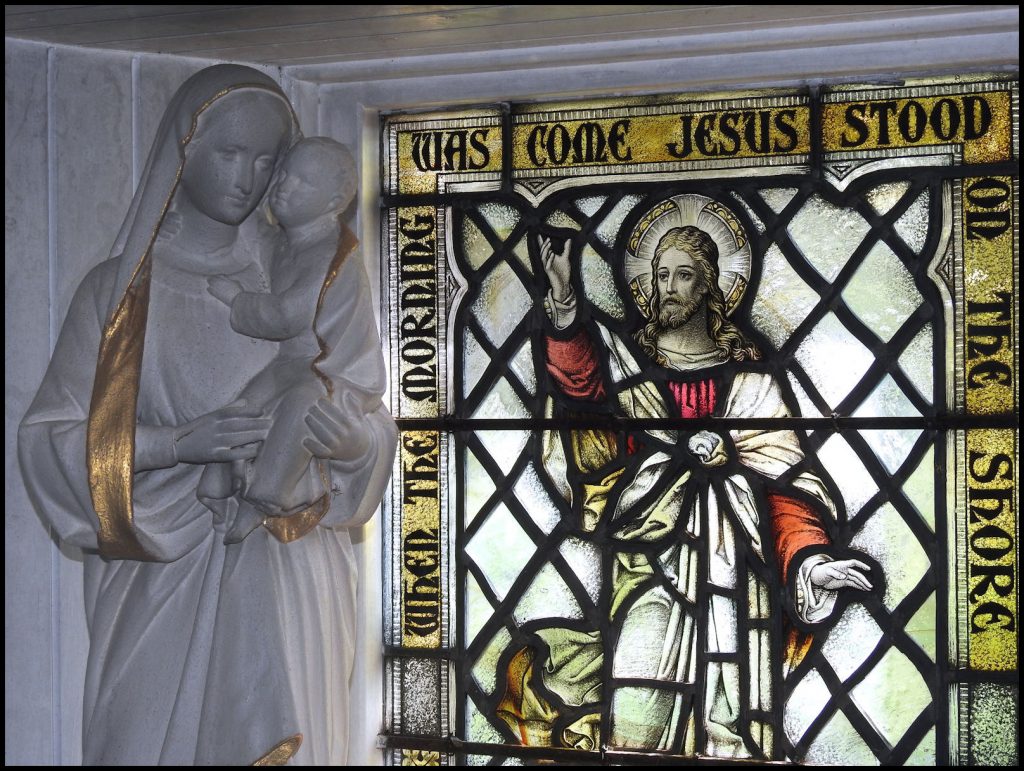

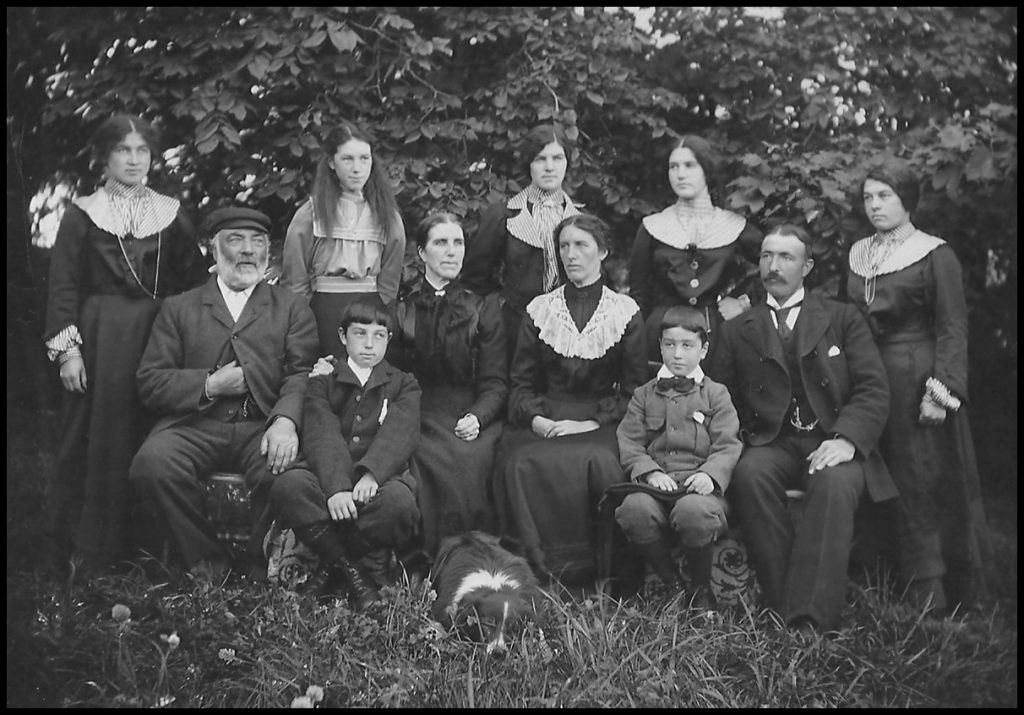

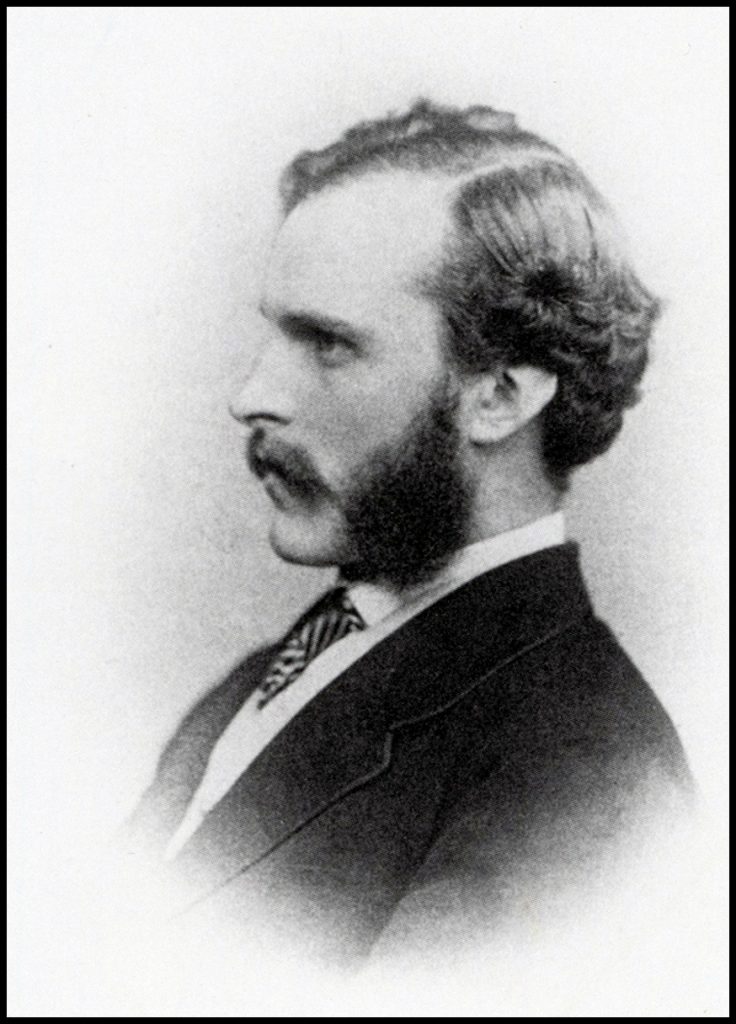

Westness House was later occupied by Thomas Middlemore, an English mountaineer who made multiple first ascents during the silver age of alpinism. His audacity earned him a reputation as the enfant terrible within the Alpine Club. He was also the head of the Middlemore Saddles leather goods company in Birmingham, England, after the retirement of his father, William Middlemore. Thomas Middlemore had taken over the management of the company in 1868 and established a bicycle saddle factory in Coventry. By his fifties he had made his fortune, sold the business and retired to Westness House, Rousay, with his wife Theodosia [Theodosia Anderson Mackay, daughter of Hugh Mackay and Margaret Annan Scott, born in 1861]. In 1898 he bought the 40,000-acre Melsetter estate on Hoy comprising the southern part of the island of Hoy, part of Walls, and the smaller islands of Rysa and Fara. The prominent Arts and Crafts architect, W R Lethaby [William Richard Lethaby 18 January 1857 – 17 July 1931] was employed to remodel the buildings. The Middlemores had been involved in Birmingham’s Arts and Crafts movement and Theodosia was a friend of May Morris, daughter of one of the main founders of that tradition, William Morris. Thomas Middlemore was 81 when he died of pneumonia at Melsetter on 16 May 1923, and Theodosia passed away in 1943 at the age of 82.

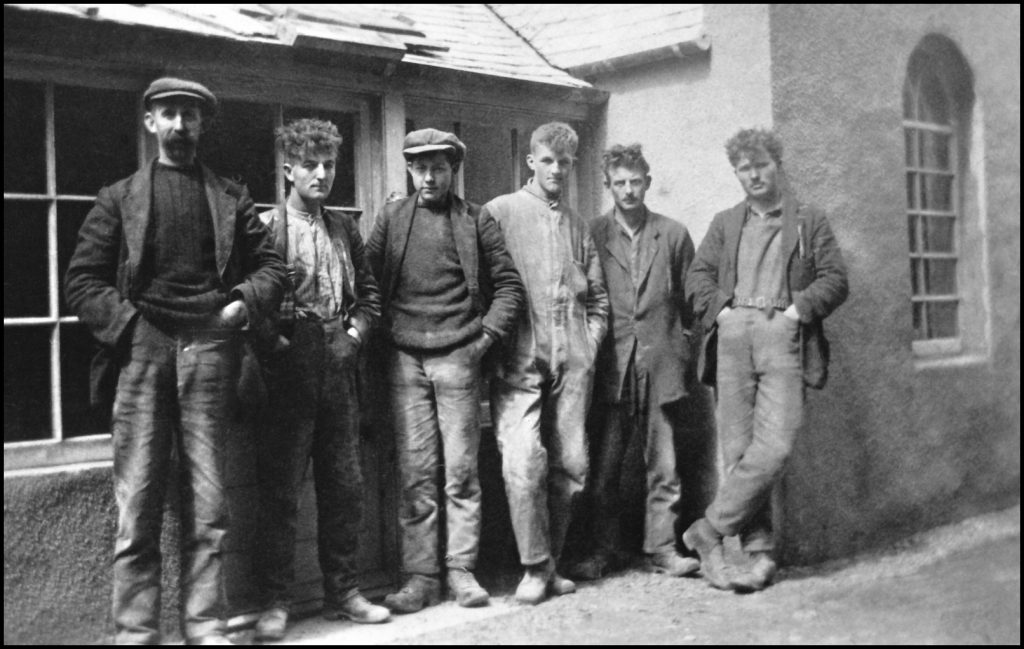

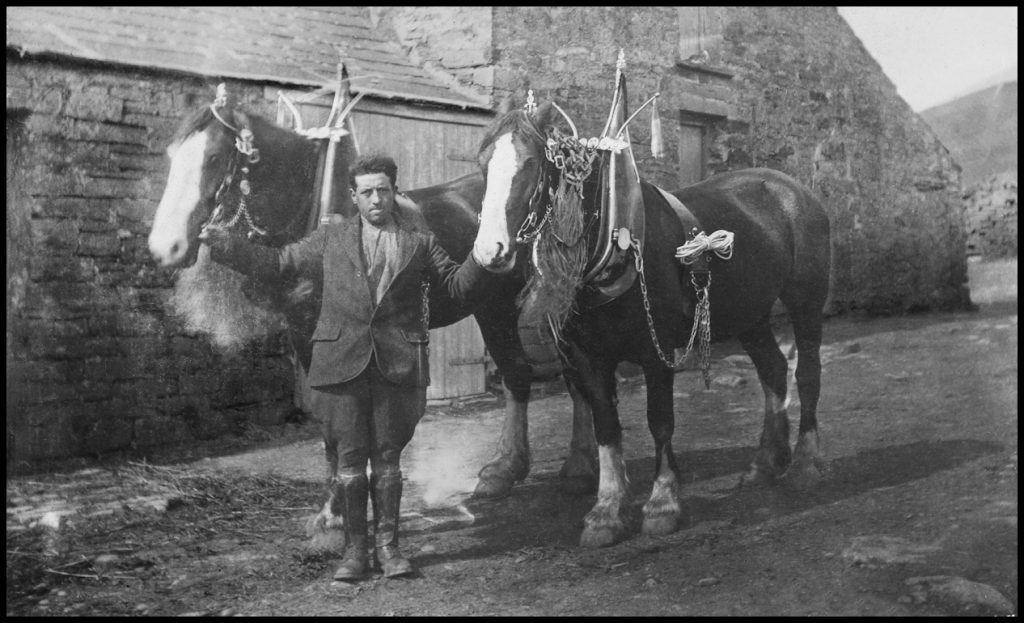

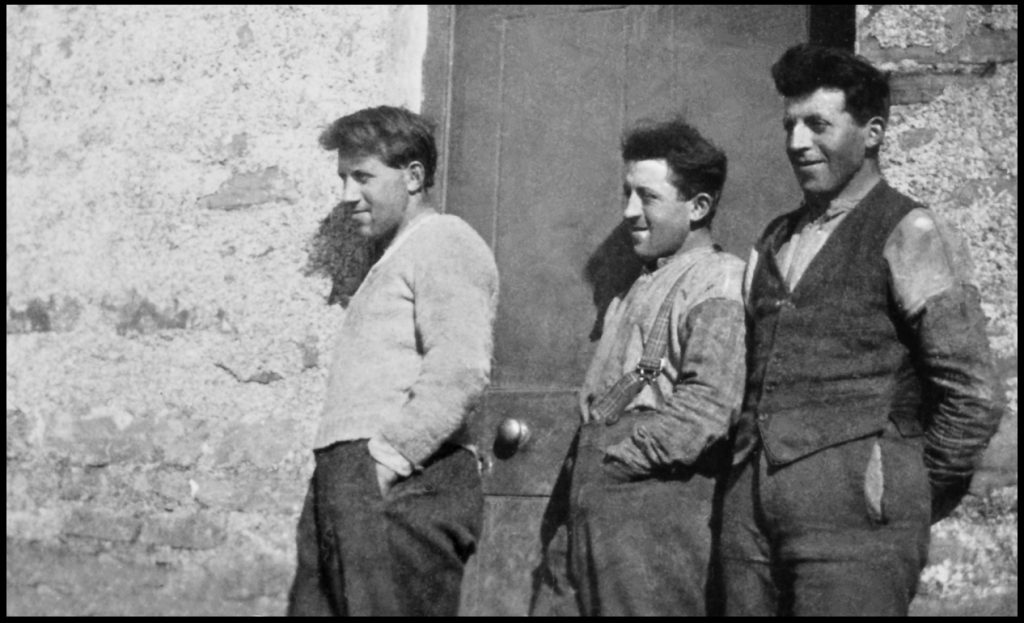

This photo was taken in 1921 at Westness House, also known as the White House in those days. The men are:- Willie Grieve, Digro; Jim Craigie Sinclair, Viera Lodge; Hughie Grieve, Fa’doon; Jim Craigie, alias Steebly, Pier Cottage; James Craigie, Corse; Stanley Gibson, Bigland.

[Courtesy of the Tommy Gibson Collection]

[Certain extracts within the body of the above text have been reproduced

by permission of Birlinn Ltd.]