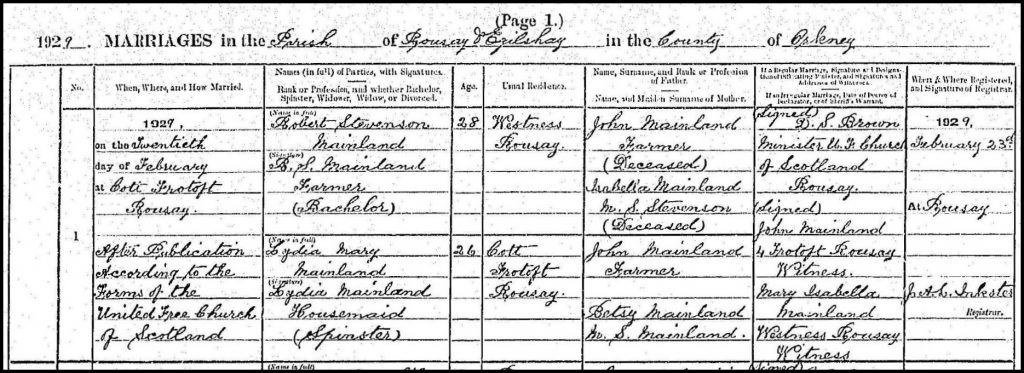

EXCAVATIONS ON BEHALF OF H.M. OFFICE OF WORKS AT

TAIVERSO TUICK, TRUMLAND, ROUSAY.

by WALTER G. GRANT, F.S.A.Scot.

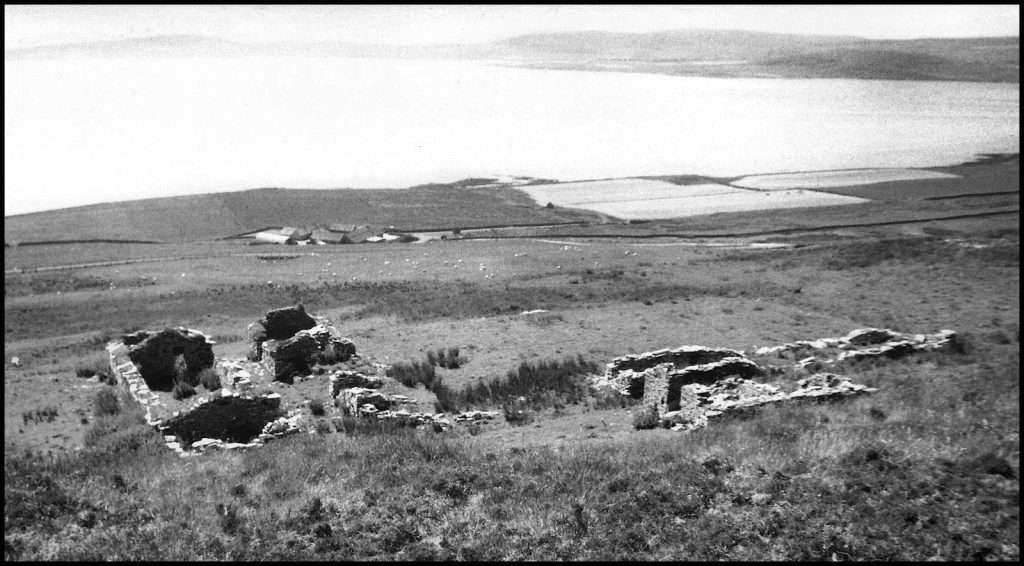

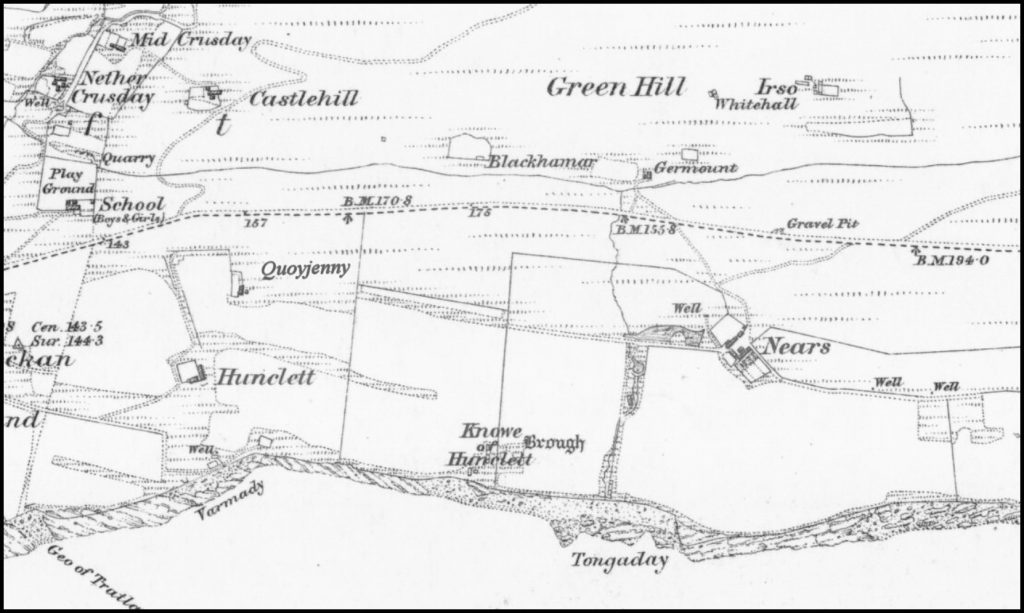

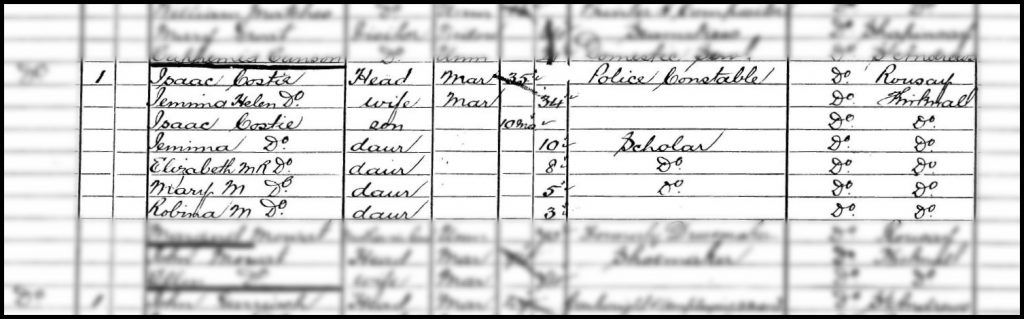

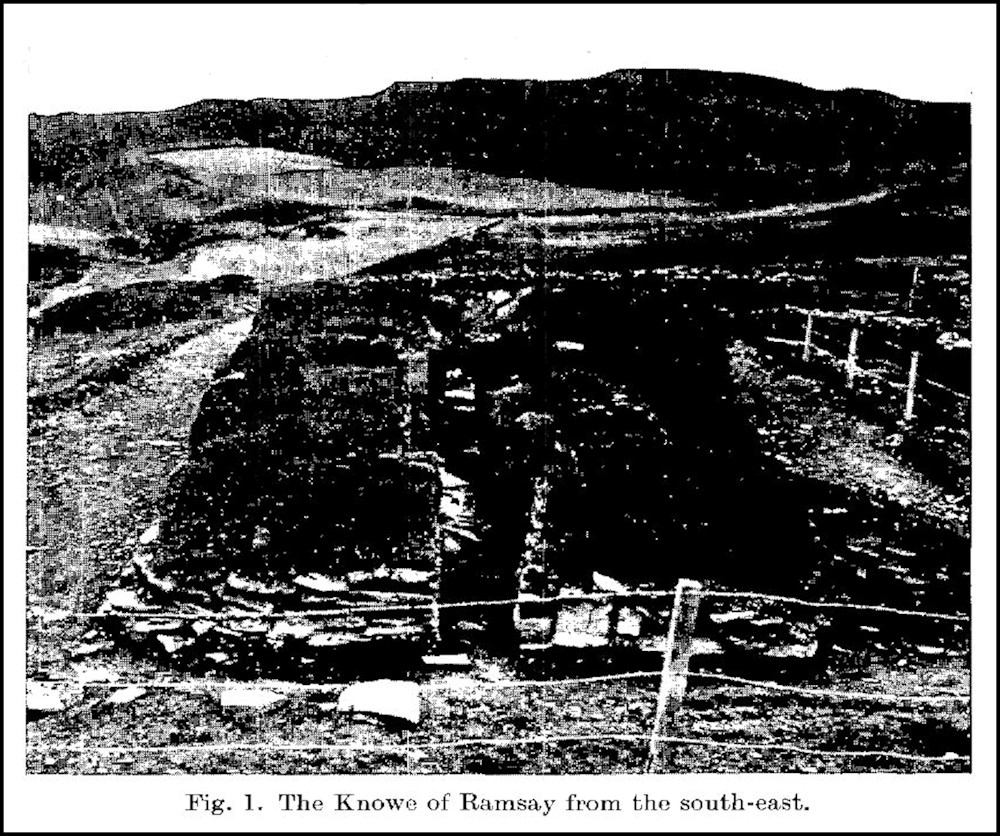

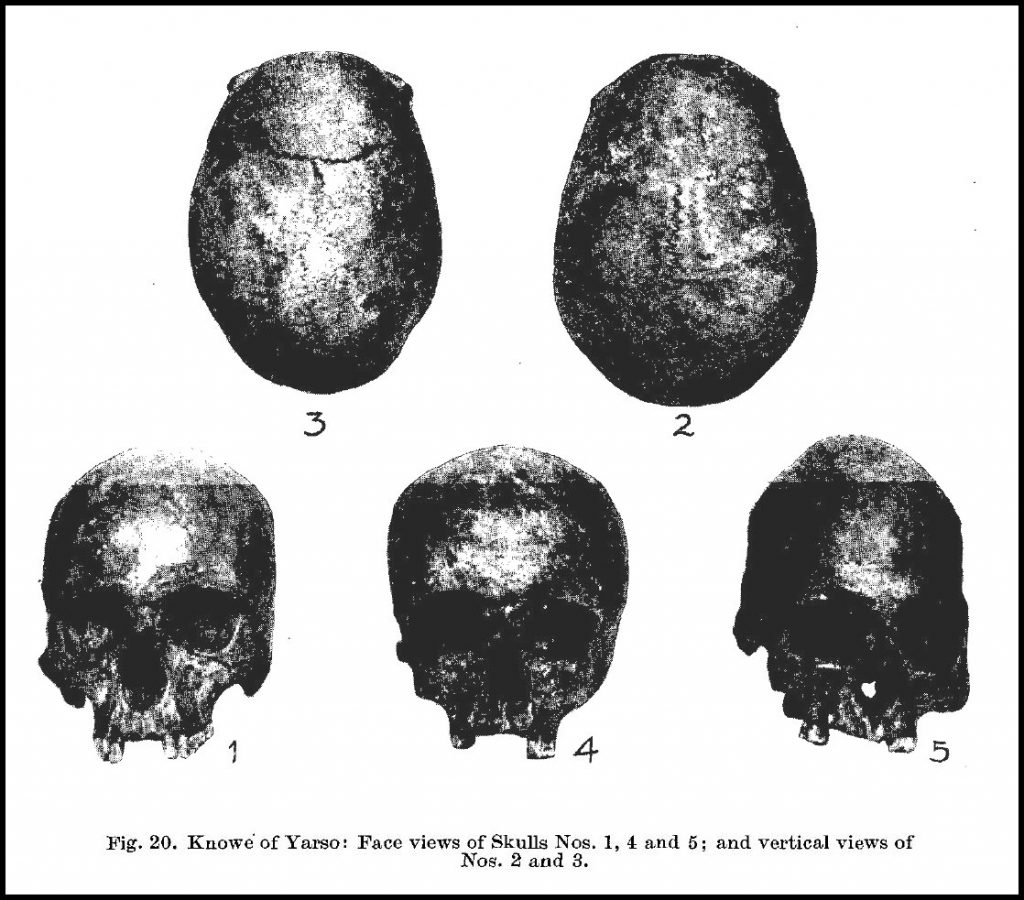

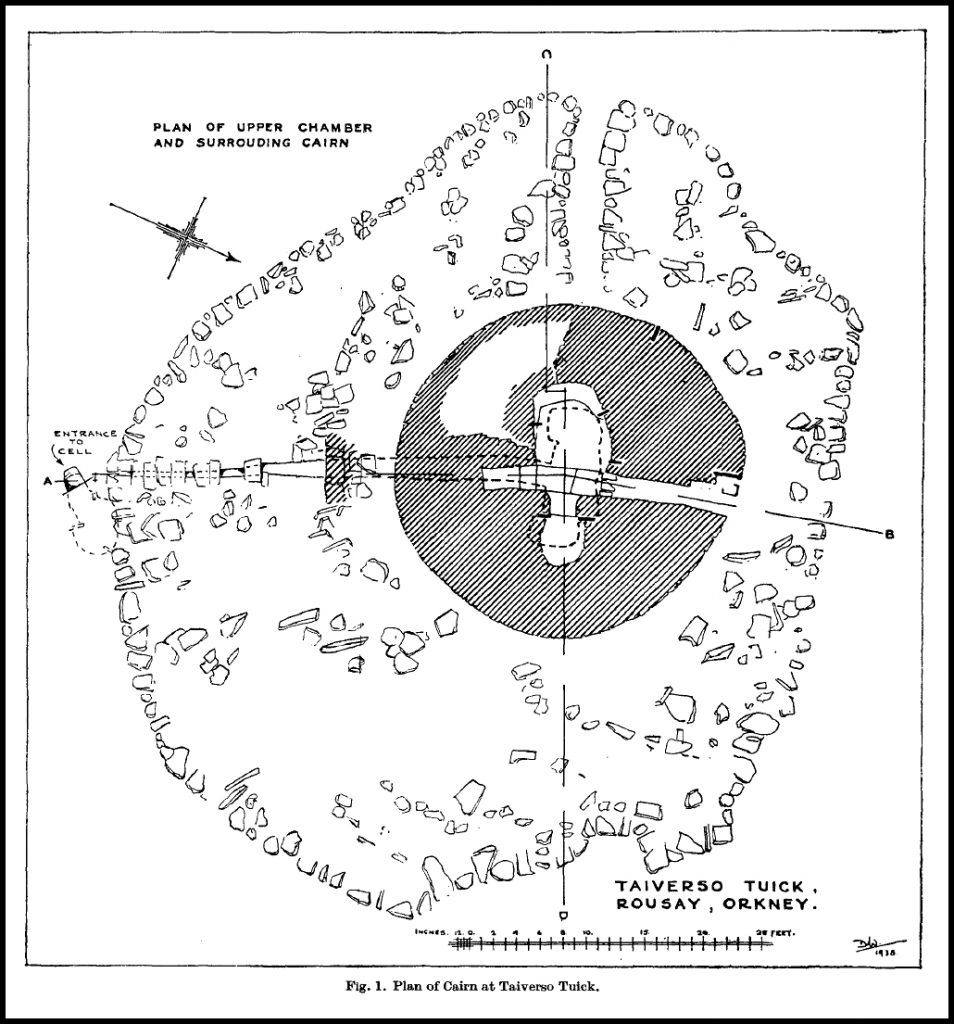

The discovery of Neolithic burial chambers at Taiverso Tuick in 1898 has been described by Lady Burroughs in a manuscript now preserved at Trumland House, and in our Proceedings, vol. xxxvii. pp. 73-82, by Sir William Turner. The discovery was an incident in the excavation of a sheltered site for a garden seat in a small mound, situated almost, but not quite, on the summit of a ridge which slopes up northward from the sea to 217.42 0.D. The mound was “about 4½ feet above the natural lie of the ground on its lower side and 2 feet on its northern side, and had a diameter of about 30 feet.” In the course of its excavation Lady Burroughs records first the exposure of “a neat, well-preserved, rough-built wall with uprights of stone slabs,” then the discovery of “three stone kists full of small bones, earth, and vitrifactions,” and finally the disclosure of a subterranean chamber. The latter has been fully described in our Proceedings, and the relics from it now repose in the National Museum. The similarity of its plan and contents to those of Unstan at once establish its character as a collective burial chamber of the type currently termed Neolithic. The “three kists” have disappeared, but as they appear to have contained cremated bones and to have “been built on a layer of earth about a foot thick” covering the lintels of the subterranean chamber, they may be regarded as Bronze Age intrusions.

The “neat wall with uprights of stone slabs” remained a puzzle to such antiquaries as have visited the site. The exposed strip of dry-stone walling terminating in upright slabs and concave to the south recalled the plan and masonry of the intact chamber below. But antiquaries were reluctant to believe that the two chambers were contemporary, since a two-storeyed burial vault would be unprecedented.

The excavations by H.M.O.W. in 1937 have conclusively established that the upper construction was really a burial vault belonging to the same archaeological period as the lower by the recovery of its complete plan, and particularly by the discovery of an entrance passage, previously blocked. At the same time the truly subterranean character of the lower chamber was defined, and a new intact chamber was revealed close to the latter’s mouth.

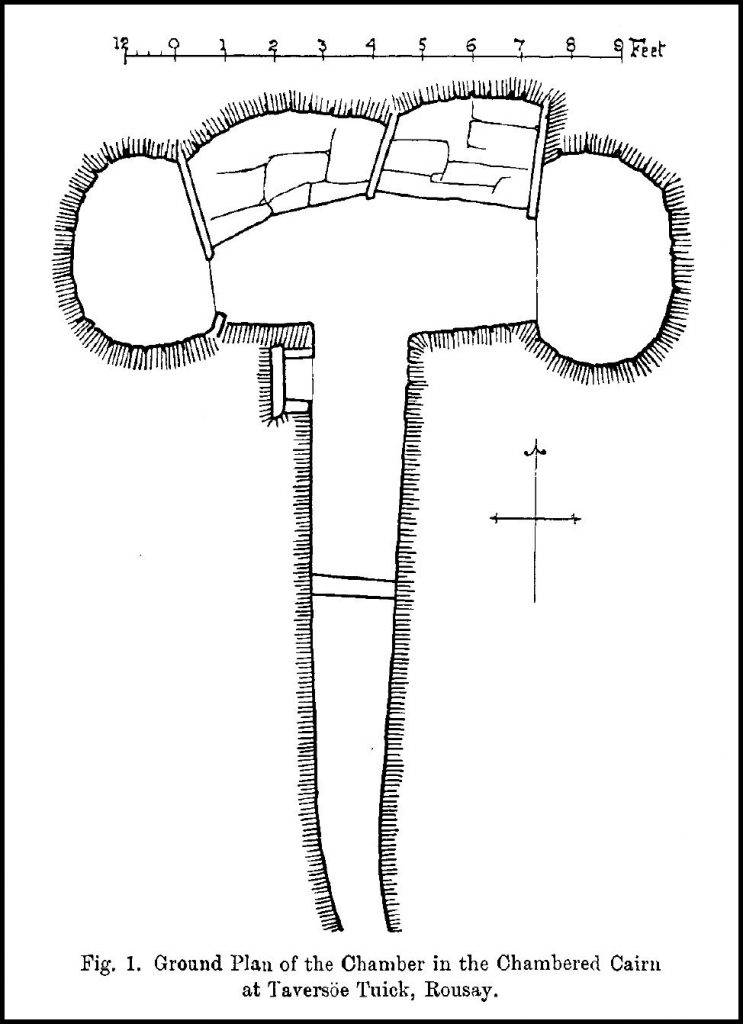

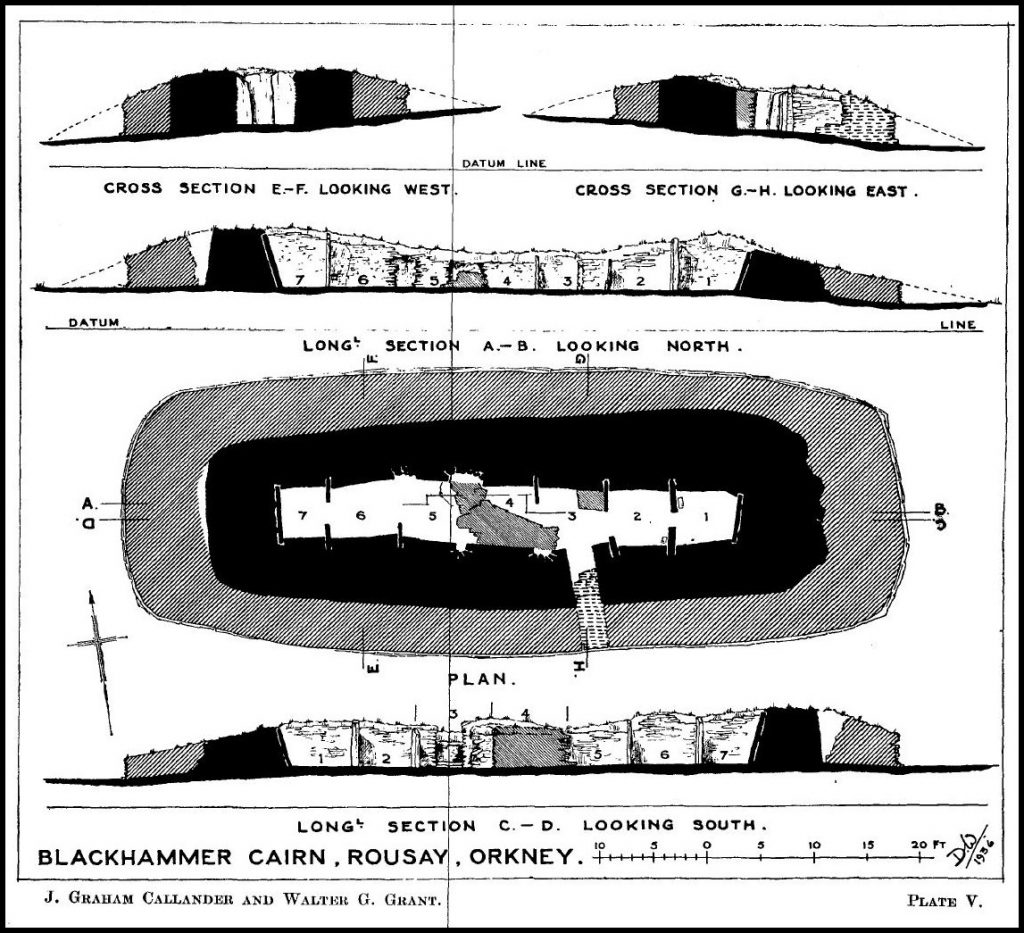

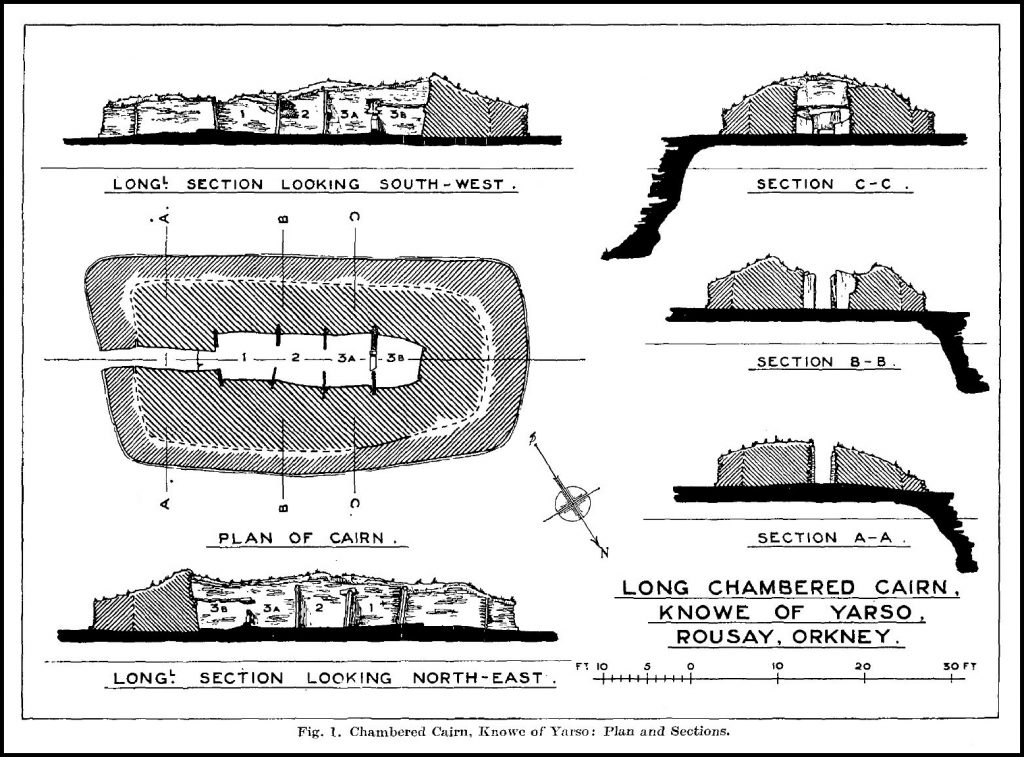

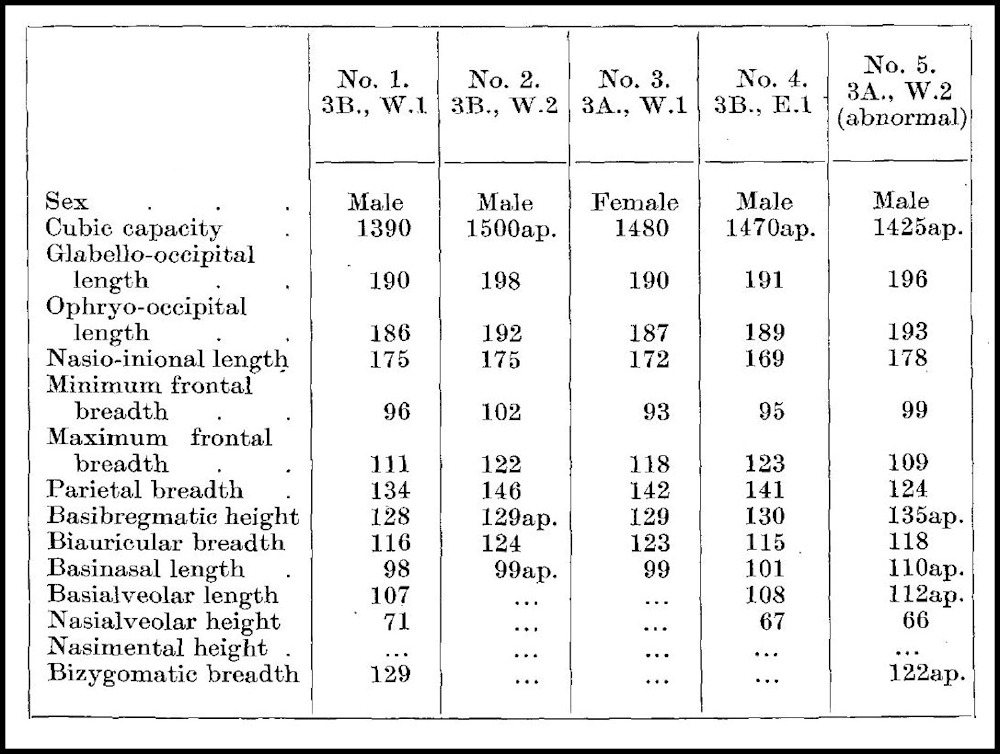

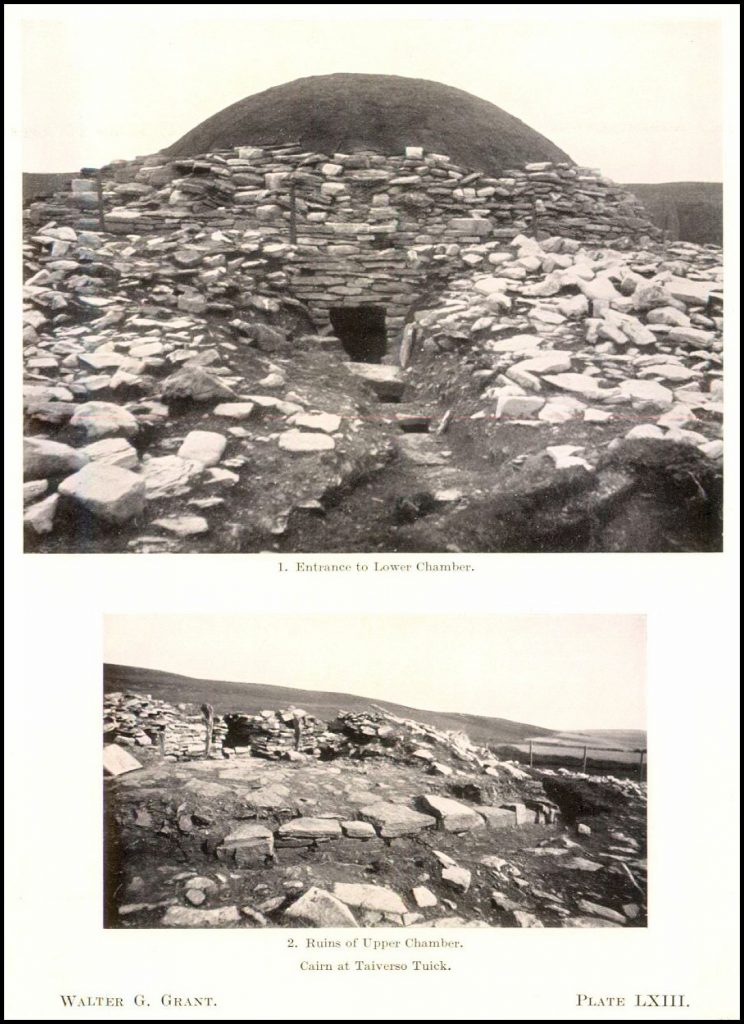

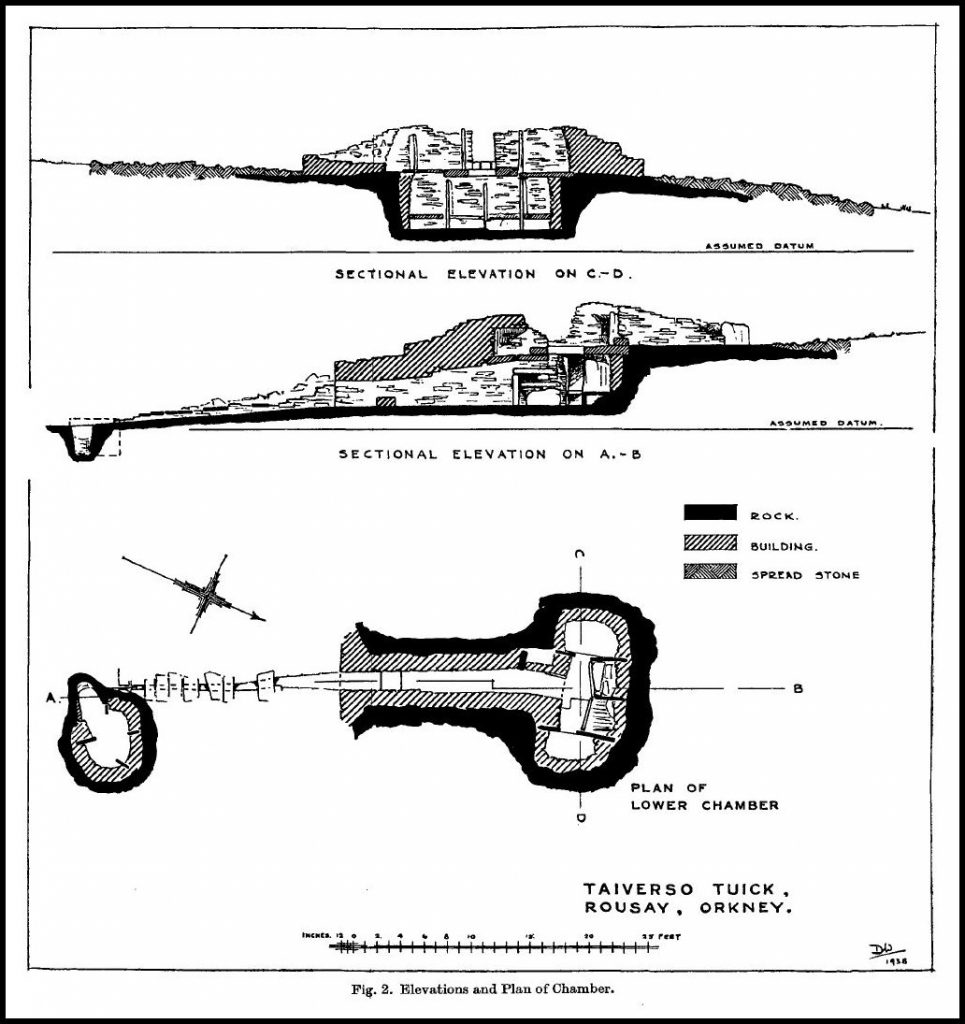

The plan of the upper chamber might be described as an oval, 15 feet 6 inches along the major axis from east to west and 6 feet along the minor axis (fig. 1). But the south side of this “oval” is really flattened out, and the east end has been reduced by truncation and restriction to a cell. The floor of this chamber is formed by the lintels of the lower one, on which the masonry of the walls rests save at No. 5 (Sir William Turner’s statement that “the westmost lintel crumbled into flakes and had to be removed” is clearly wrong, since the lintel in question, No. 6, is still in position with the intact walls of the upper chamber resting upon it. His statement may, however, mean that a flooring slab had once rested on lintel No. 6). Save at the east end there was no trace of a prepared clay floor resting upon the lintels such as Mr Calder observed in the upper chamber at Huntersquoy, Eday. However, the upper surface of the eastern-most or first lintel, which forms the floor of the eastern cell of the upper chamber, is 7½ inches below that of the second lintel and the rest of the chamber floor. This disparity was partially rectified by a layer of local clay on the floor of the east end, and this survived to a depth of 2 inches under the masonry of the east wall. The crumbled lintel or flooring slab at the westmost end removed by Turner might have rectified the existing disparity in levels between lintels 5 and 6; the former being some 2 to 3 inches higher than the latter.

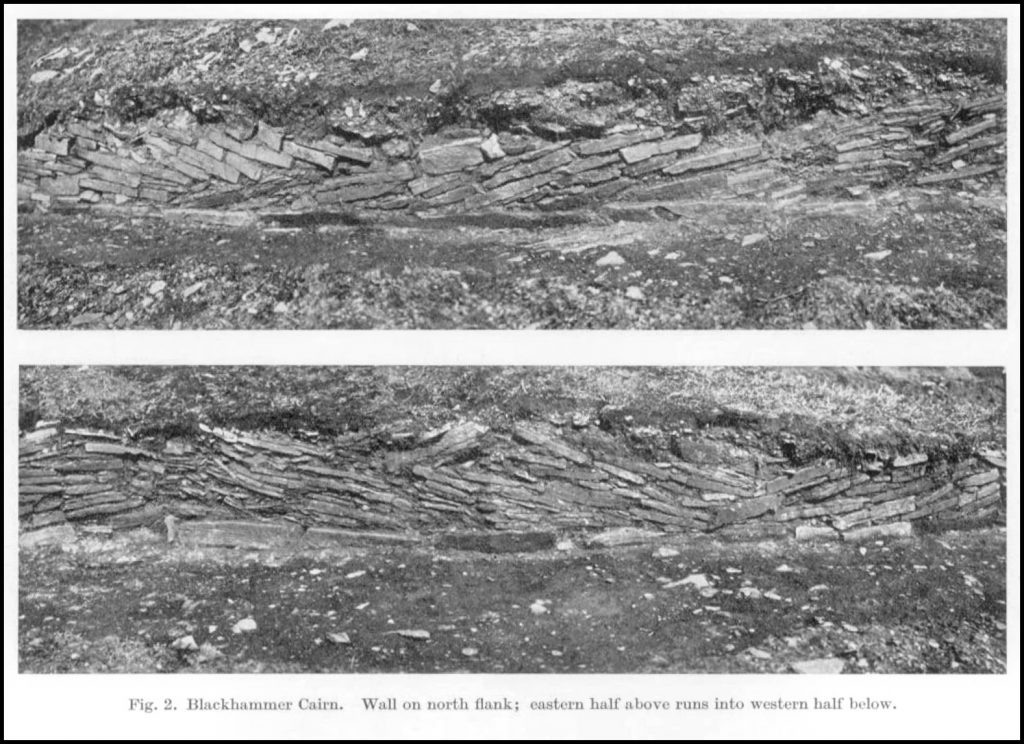

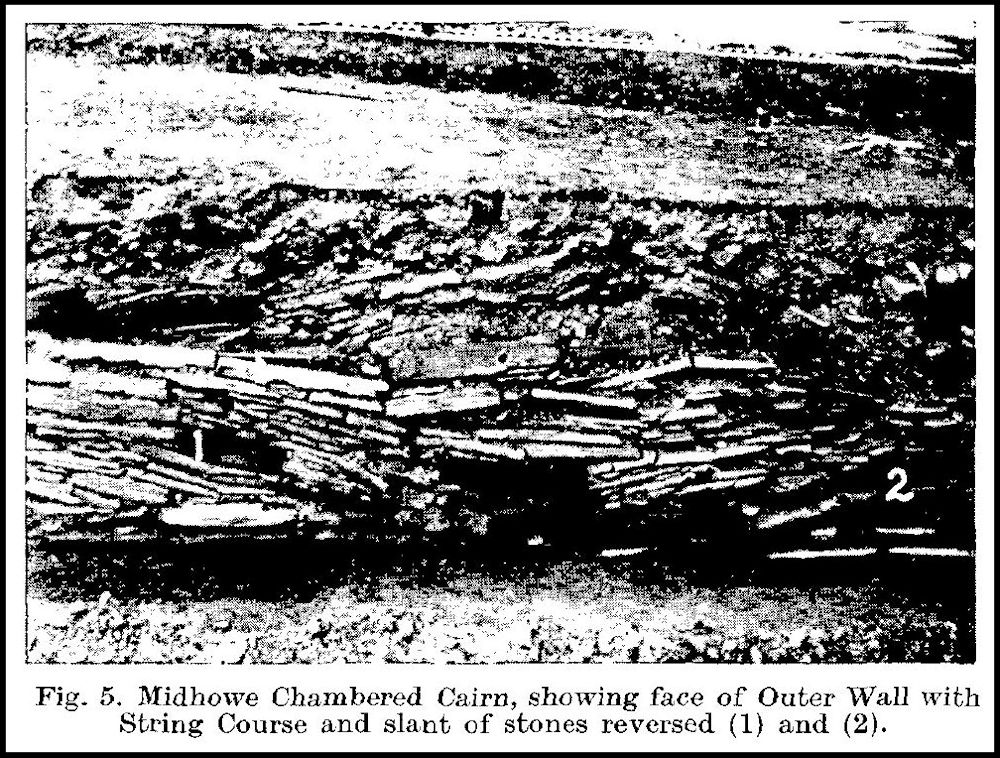

The lintels of the lower chamber not only provide the floor of the upper, but they also condition the planning of its masonry. The skeleton of the chamber walls may have been formed, as in Caithness, of slabs on edge transverse to the line of the walls. Of such, three survive in the north wall (Pl. LXIII, 2) and one in the south; Mr Richardson detected the gap for a second slab in the two surviving courses of masonry of the south wall opposite the westernmost slab on the north wall, and a slab, actually found in the debris filling the west end of the chamber, has accordingly been set up in the gap. The two eastern slabs form a pair, both resting upon the first lintel and with their faces against the edge of the high second lintel. They serve to frame the portal to the eastern cell. The surviving western slab stands, not on lintel 5, but on virgin soil beyond its end, and the same is true of its southern counterpart as now set up. Between the slabs of this skeleton the walls are formed of coursed masonry. As far as they survive, the inner faces of the masonry are almost flush with the edges of the uprights, so that the latter do not effectively serve either to divide the chamber into compartments or to frame stalls.

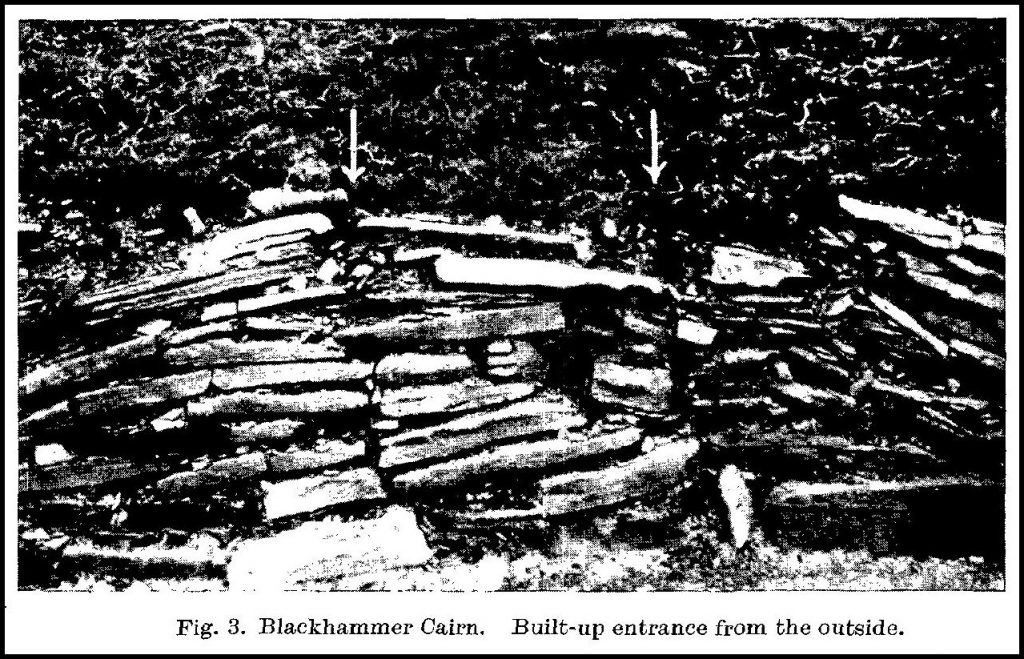

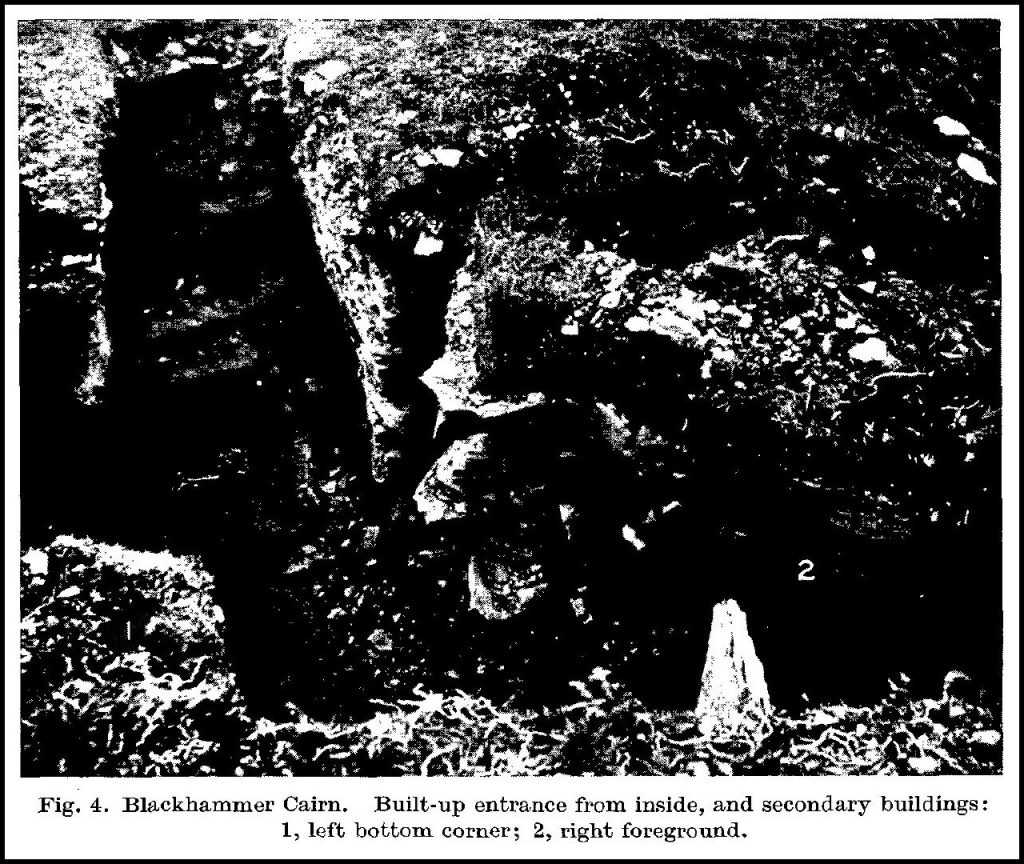

Entrance to the chamber was provided by a passage, 1¾ foot wide and 11 feet long, opening rather east of the centre of the north wall immediately west of the large lintel 2 of the lower chamber. The passage is lined throughout with dry masonry, surviving in places to a height of 3 feet, the basal course of the east wall for a distance of 3¾ feet being formed by lintel 2, the western edge of which defines the line of the wall. The passage was, however, found blocked with similar masonry at its inner end, a phenomenon noted in comparable burial-places in Scotland and elsewhere. The ends of the building slabs forming the west wall of the passage also constitute the north wall of the chamber between the passage mouth and the central upright, a distance of 10 inches. Between the central and western uprights the north wall is slightly concave, and, perhaps owing to slip, seems corbelled, so that the overhang against the west upright, 3 feet from the floor, is already 8 inches. Beyond the upright the wall curves inwards more rapidly and the oversailing is accentuated, so that immediately west of the upright the last surviving course, 2 feet 4 inches from the floor, projects as much as 2 feet beyond the line of the foundation course.

The south wall is nearly straight from the south-west corner of the rounded western end, but it has been so much damaged in the preparations for the shelter that for most of its length only two courses of masonry survive, and only a gap between the horizontal slabs opposite the west upright in the north wall indicated the position of the counterpart which has now been set up by the Office of Works.

Be that as it may, the south wall turns south at a right angle, 5 feet 8 inches from its western end and precisely opposite the mouth of the entrance passage, to give access to a recess or cell. The entrance to the latter is 2 feet wide. Beyond the gap the line of the south wall is not continued, but the east wall of the recess is continued northward 1 foot 4 inches beyond that line along the western margin of lintel 2. Similarly the east wall of the entrance passage is continued 2 feet farther south than the north wall along the same lintel’s edge. The two masonry piers, formed by the continuation of these walls, end in carefully rounded corners, beyond which both walls run eastward, only 2 feet apart, for a distance of 2 feet across lintel 2 till they abut against the easternmost pair of uprights which, as noted above, are set against the eastern edge of lintel 2. The piers thus border a short passage which leads, through the portal formed by the uprights, to the east compartment or cell. The latter is horse-shoe-shaped. The floor, as noted, is some 7 inches lower than that of the main chamber (Pl. LXIV, 2).

The provisional description of the upper chamber might therefore be amended by describing it as an oval truncated at the east end, with a horseshoe cell at that end and a second cell in the south wall. The latter cell is really little more than a passage 4½ feet long and about 2 feet wide continuing the line of the entrance passage and almost above the entrance of the lower chamber. For the first 1⅔ foot the floor of the cell is formed by lintel 3, beyond the latter’s south end by the lintels roofing the passage of entrance to the lower chamber. Even the innermost of these lintels is some 6 inches below the surface of lintel 3, so that most of the cell lies at a lower level than the main chamber. The deep inner part of the cell is roofed with two lintels, 2 feet 6 inches from its floor, but no lintel survives over that part which is paved by lintel 3. The rear wall of the cell is straight and vertical and not very effectively bonded into the side walls, so as to give rather the impression of a blocking.

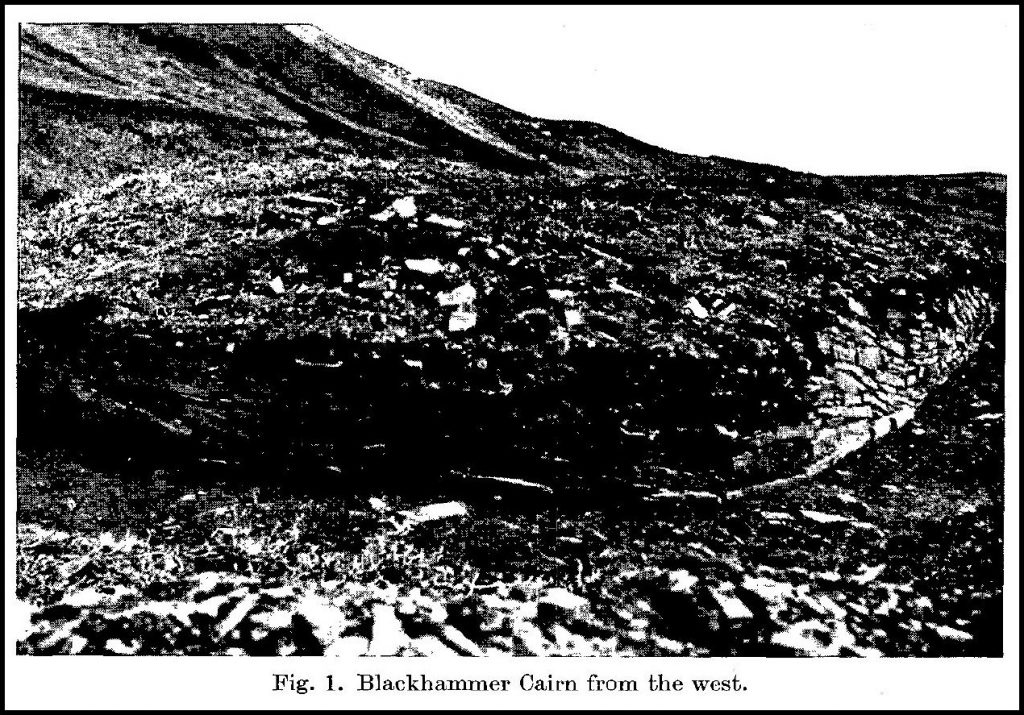

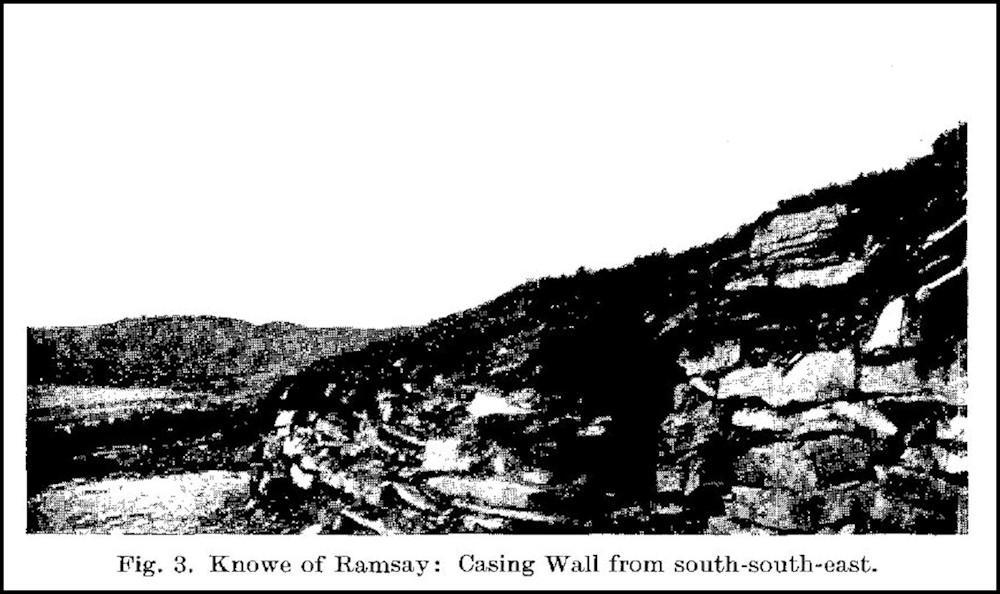

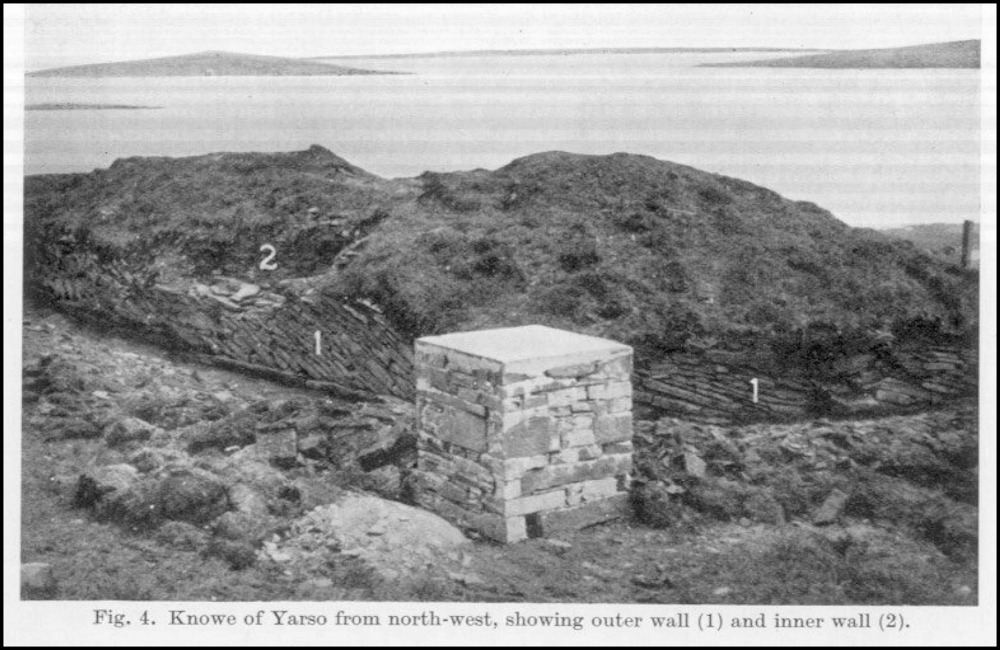

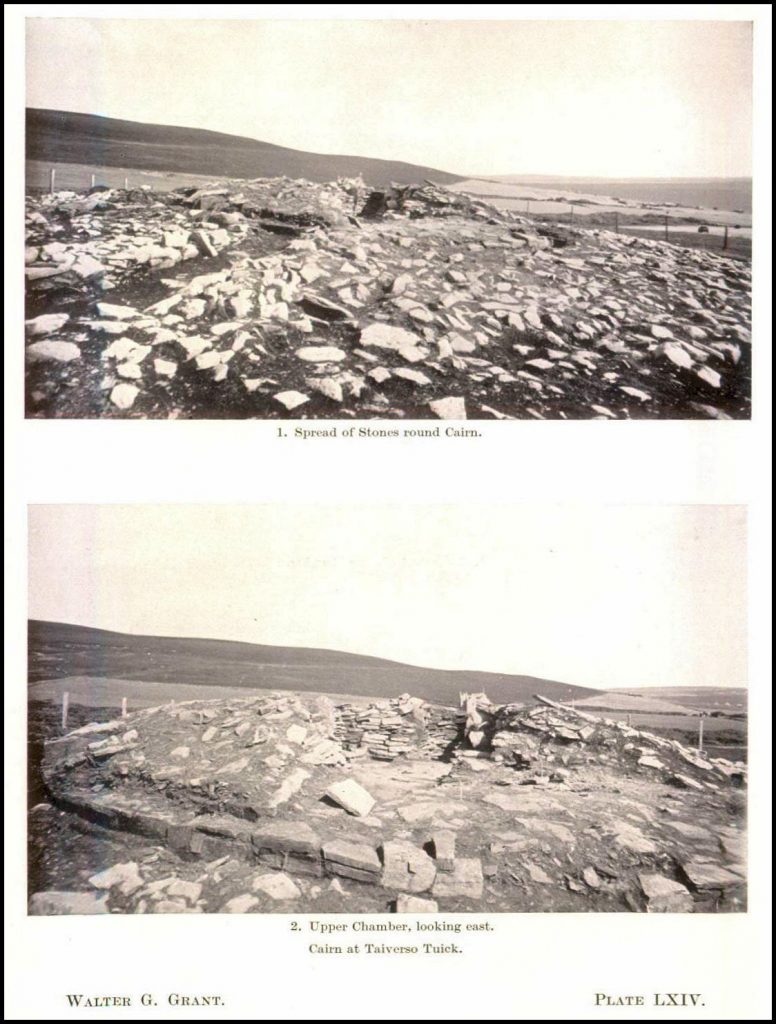

The upper chamber was covered with a cairn bounded by an almost circular retaining wall. This is bonded into the wall of the entrance passage on the east. On the west side of the entrance, though a single surviving course of masonry carries on the line of the passage to the circumference of the cairn, the retaining wall only begins again west of a flat slab on edge set parallel to the passage wall and 1½ foot back from its line at the western corner of the entrance. Between the line of the west wall and this slab only rough blocking survived, so that there may originally have been a sort of recess on this side of the entrance. A second slab on edge is built radially into the retaining wall 16 feet farther west. Beyond the retaining wall a thin spread of stones extends for about 11 feet towards the summit of the hill to the north and west and 24 feet down hill on the south (Plates LXIII and LXIV, 1). No trace of an outer wall or peristalith could, however, be found, though a careful search for one was made at Mr Richardson’s request. However, a curious alley, clear of stones and roughly bordered with boulders (not building slabs), leads through the stony area to the base of the cairn’s wall on the west (Pl. LXIV, 1). It is possible that this is somehow connected with General Burroughs’s operations, though there is no evidence to support this contention.

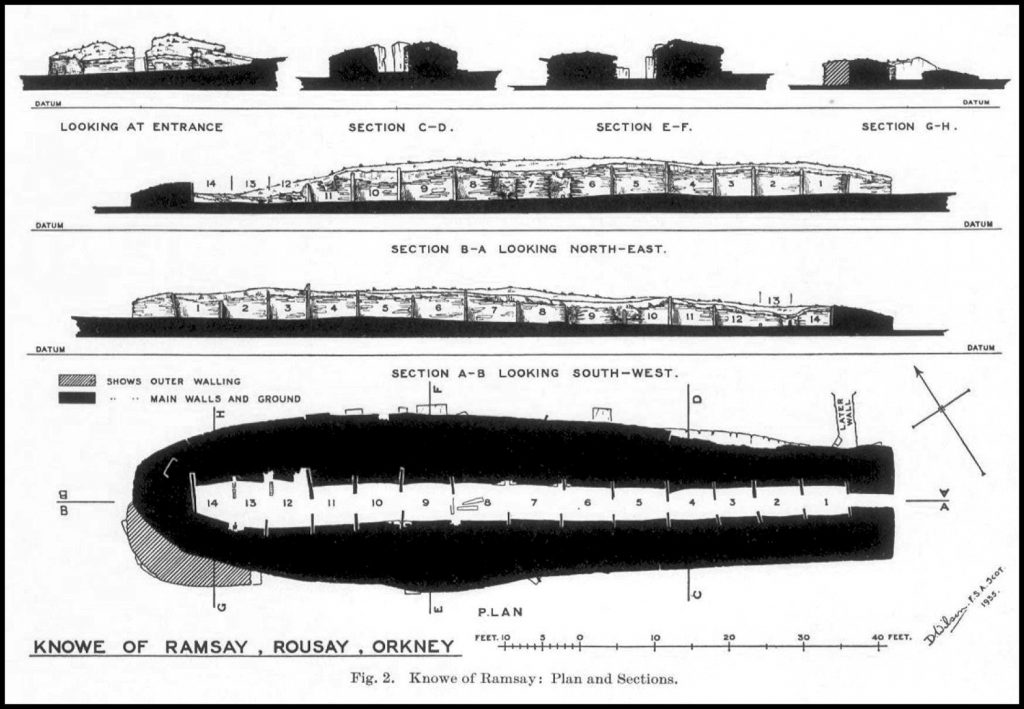

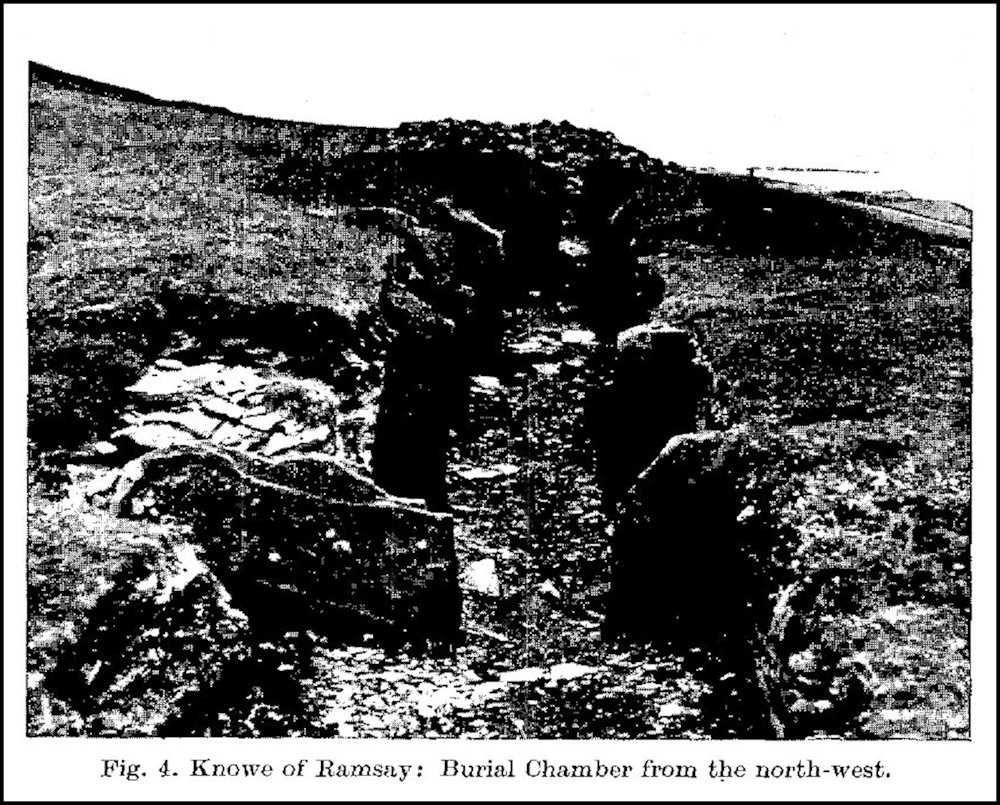

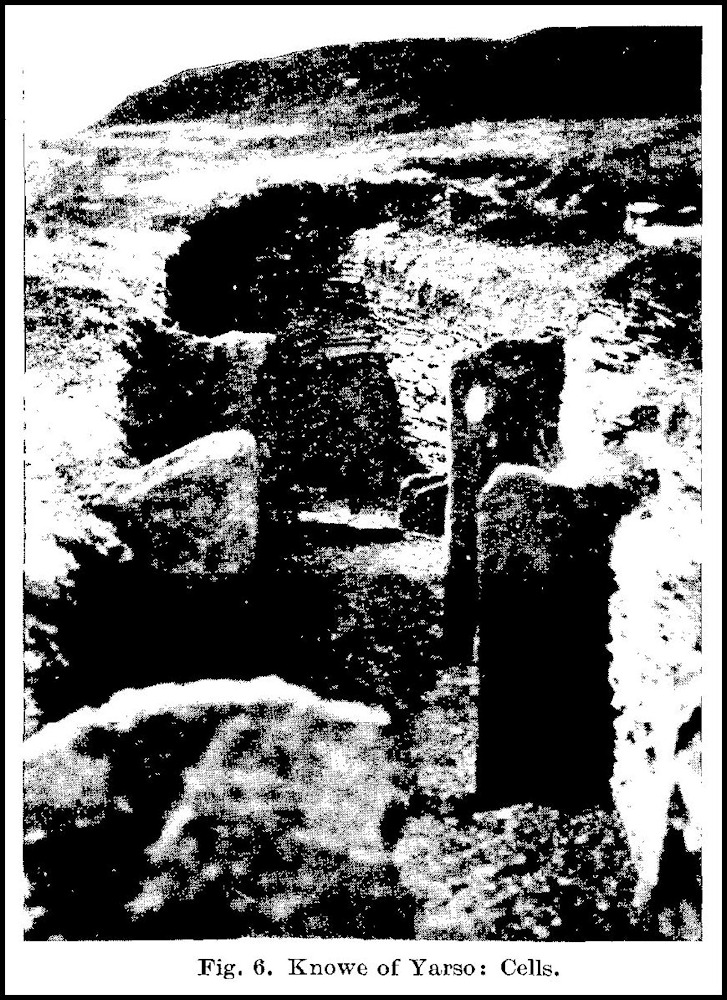

The chamber just described is built above and upon the lintels of a smaller subterranean chamber (fig. 2). The latter has been adequately described already by Sir William Turner. The chamber, with a total length of 12 feet, a maximum width of 5⅓ feet, and a height of 4⅔ feet is, like the upper one, constructed round a skeleton of five uprights, but is entered from the south. The south wall is almost straight and vertical. The rear wall is built in two segments on either side of the central upright, both concave. The ends are curved, forming cells like flattened horseshoes. The three slabs in the north wall project to form stalls occupied by benches formed of slabs raised 1 foot above the floor. The end compartments, similarly benched 1½ foot at east and 1 foot 1 inch at west above the floor, are separated from the central part of the chamber by the portals formed by the paired uprights in the south and north walls, but the southern uprights do not project appreciably beyond the line of the wall-face. While the front wall is practically vertical, the end and rear walls slope inwards in four distinct segments, but this seems due to slip rather than deliberate corbelling. Eke stones have been inserted above and behind the uprights where these do not reach the level of the lintels.

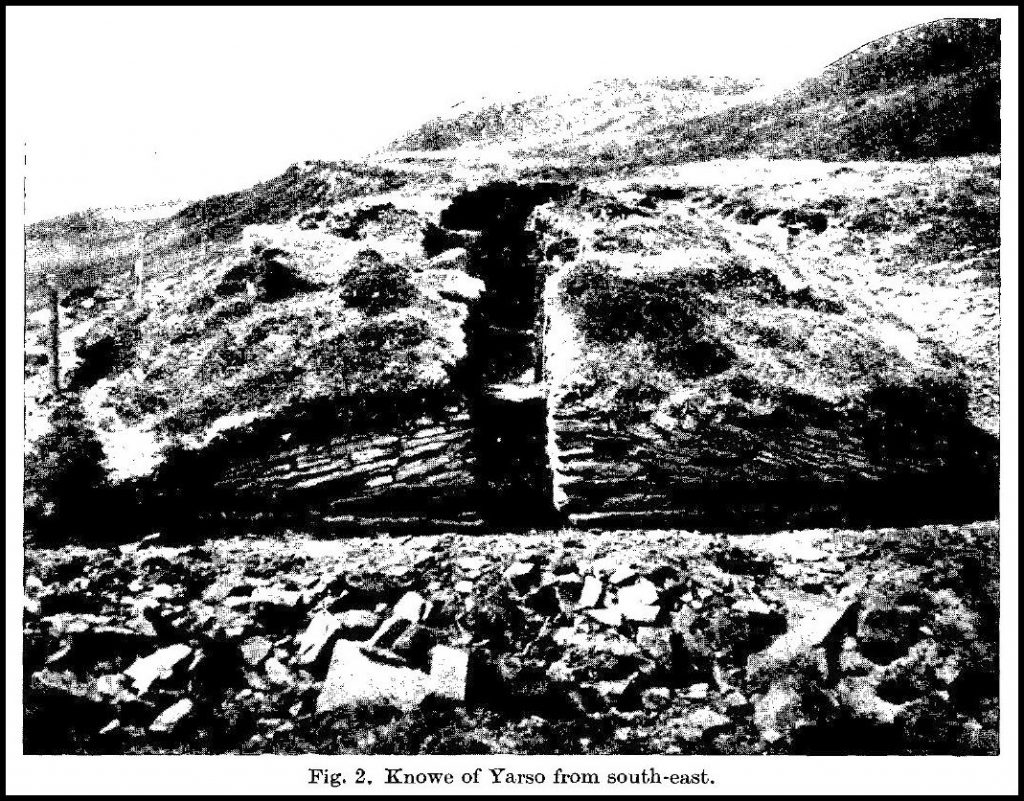

The entrance passage, which contracts outward, was found partially blocked by a slab fitted into the side walls some 13½ feet from the chamber but continued roofed for a total length of 18 feet, beyond which an open trench, to which we shall return later, extends for a further 19 feet.

The most striking fact about the lower chamber, not sufficiently emphasised in the original report, is that it is built entirely in an artificial excavation in the hillside, the masonry walls off chamber and passage being merely a lining to the crumbling rock and clay of the shaft. The excavation had been carried down by the tomb’s builders to a horizontal bed of fairly solid rock which actually forms the chamber floor. A quarried ledge of similar rock forms the basal course of the south wall, west of the entrance. The irregularly sloping rock-face of the excavation is also exposed under the benches of the terminal compartments and the northern stalls, the bench slabs actually reposing at the back on ledges of rock though supported in front by building, and in a gap of the passage’s western face, 2 feet 6 inches from the chamber. Here the rock lies 1⅔ to 2 feet behind the face of the passage wall some 2 feet above the floor, with loose stones lying between the back of the wall and the rock. By careful removal of a stone just below the first lintel in the north-east corner the natural clay capping the rock was found about 10 inches behind the wall-face (see Sections A-B and C-D on fig. 2).

The lintels of the roof too, while undoubtedly supported by the masonry walls, generally rest also on the solid ground beyond the limits of the original excavation. Lintel 1 (on the east) extends under the walls of the upper chamber well beyond the limits of the lower’s masonry walls. The enormous second lintel, 10 inches thick and over 9½ feet long, was proved to be embedded on solid clay at its northern end so that some 1¾ foot of its total length probably rests on solid ground. The sixth lintel likewise rests on the same solid clay ground as the end walls of the upper chamber. A comparison of the plans will show how the upper chamber’s walls, even when resting on the lintels of the lower, are in most cases vertically above, not its masonry walls, but the walls of the original pit. The passage too must originally have been an open trench subsequently lined with masonry and lintelled over for a distance of 18 feet. Beyond the lintelled section the sloping walls of this trench cut in the solid are actually visible to-day. And at the mouth of the roofed section the uppermost 18 inches of masonry are carried round for some 1¼ foot on either side so as to abut against the sloping walls of the trench (Pl. LXIII, l).

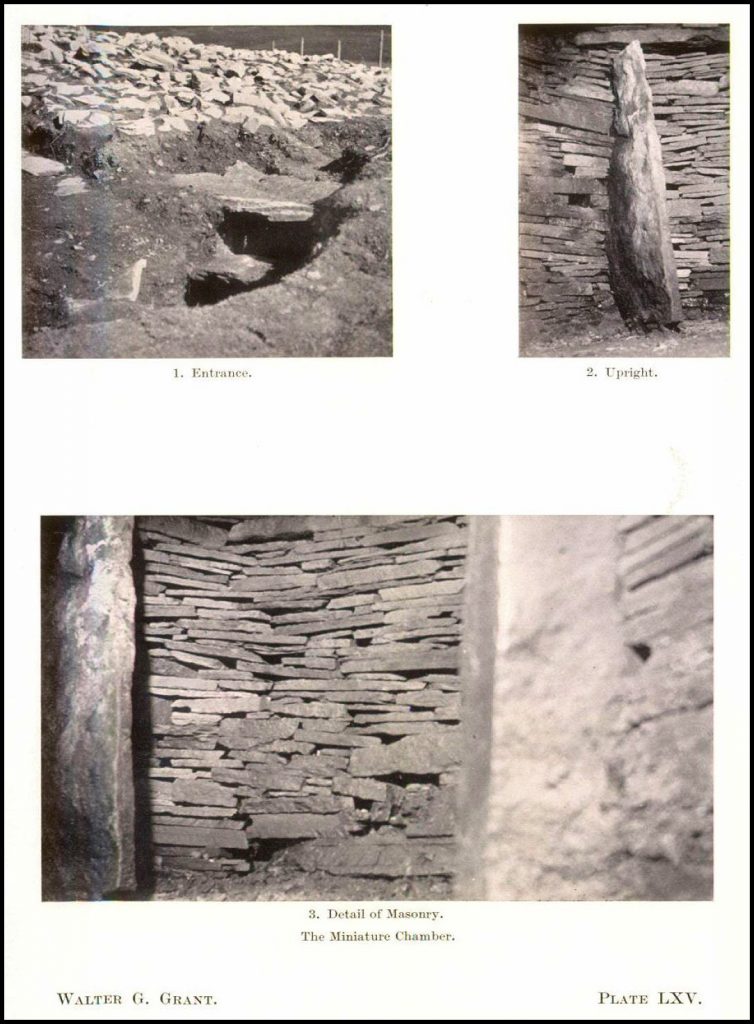

The passage does not terminate, as might have been expected, where the natural slope of the hill would bring its floor level with the ground surface, some 20 feet out from the chamber. It is continued as a narrow channel, only 18 inches wide, tapering to 2½ inches wide for a further 19 feet. The walls of this channel are lined with masonry, continuous with that lining the passage, and it is, moreover, roofed with miniature lintels, some 9 inches to 2 inches above its floor, though only six of these were in position in 1937. This small channel gives the impression of being a drain, designed to carry off water from the main chamber. But Lady Burroughs remarked in 1899 that it could not fulfil such a function owing to the blocking stone 13½ feet down the passage already mentioned. In fact no discharge along the channel was observed during the heavy rains of July 1938. No water percolated into the chamber through the side walls, and the rain that had come in through the broken roof seeped away in a day. Accordingly, the natural joints and bedding plains of the rock must provide sufficient drainage to make an artificial outlet for water unnecessary. Finally, the channel terminates at the mouth of a miniature rock-cut chamber, so that any moisture it carried would be discharged into the latter.

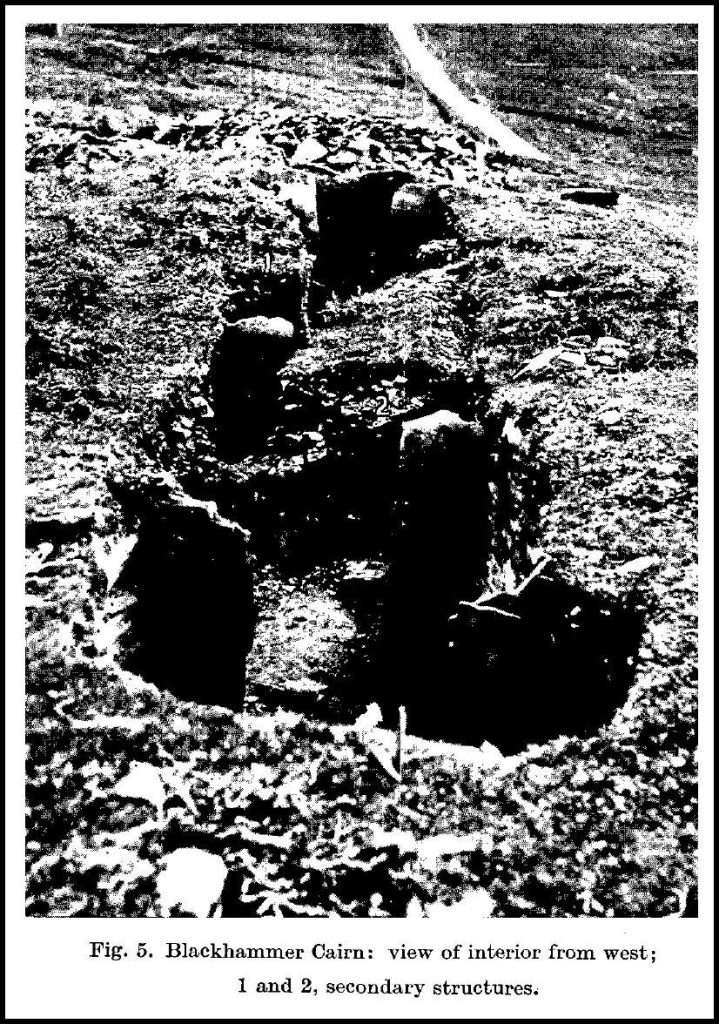

As noted earlier, the upper chamber is bounded by a retaining wall, while beyond this is a spread of stones with no outer wall or peristalith. Tirring and excavation, to define the area of this spread, was carried out in 1937, and in doing this a “loose stone” in being removed brought into view the interior of a small subterranean cell situated at the termination of the continued “trench or drain” from the lower chamber (Pl. LXV, 1).

Very little soil had percolated into the cell past the crude blocking, if such it were, and cleaning out revealed a horseshoe-shaped subterranean chamber hewn out of the rock and lined with most precisely and perfectly built masonry, and having an unlined rock-hewn entrance way leading into it from the south-west (fig. 3, below). Examination of the entrance showed that the chamber plan had been primarily hewn out of the natural rock, which is split off in layers approximately 1 inch thick, and suggests, at the downward sloping entrance, miniature steps. This entrance passage, 2 feet 3 inches long and widening from 12 inches to 2 feet 3 inches at the chamber mouth, has a flat rock floor, level with that of the chamber, and is now spanned by a single lintel stone 13 inches wide and 3 inches thick at 1 foot 9 inches from the floor, supported on the natural rock at it northern end and on a slab on edge at its southern end. This slab on edge, which suggests a door portal, has no counterpart on the north.

The chamber or cell, the main axis of which south-west to north-east is 5 feet long, and minor axis south-east to north-west 4 feet 3 inches long, is roofed with three lintels at from 2 feet 6 inches to 2 feet 11 inches above its flat and level rock floor. There are four slabs on edge set radially to the chamber: No. 1 to the right on entering the chamber projects some 3 inches beyond the masonry which lines the chamber between the right “door portal” and No. 1 slab and 11 inches from the walling to the north-east; No. 2 projects some 5 inches to 12 inches beyond the masonry walls; No. 3 is practically flush with the walling; and No. 4, projecting 3 inches from the chamber’s masonry wall, has no abutting building work on its passage or south-west face, and shows its full width of 6 inches. The walling to the chamber between slabs 1 and 4 is built concave on plan giving a horseshoe shape, but it runs up quite vertically from the floor in height. The floor, as previously mentioned, is flat and level and hewn out of solid rock, as is noted particularly between slabs 1 and 2, where the rock shows 5 inches to 9 inches above floor-level before building begins. The built walls, plumb from floor to roof, are constructed of the rock obtained from the quarrying of the chamber shape. As stated earlier in this report, these walls are of precisely and perfectly built masonry, and show as many as 39 stones in a height of 2 feet 7½ inches, with a remarkably even face and a complete absence of any projecting or protruding stones. One of the roof slabs had fractured and dropped slightly in the centre, but otherwise the chamber was intact, clean and dry, and contained 4 vessels. The fact that the room was clean and dry should be particularly noted when it is recalled that the mouth or outlet of the trench or drain from the lower of the two chambers previously described is only some 2 feet from the mouth of the cell and 2 feet 6 inches above its floor. Of constructed or deliberate blocking there was no evidence, only a little debris and stone filling up the entrance proper.

THE RELICS.

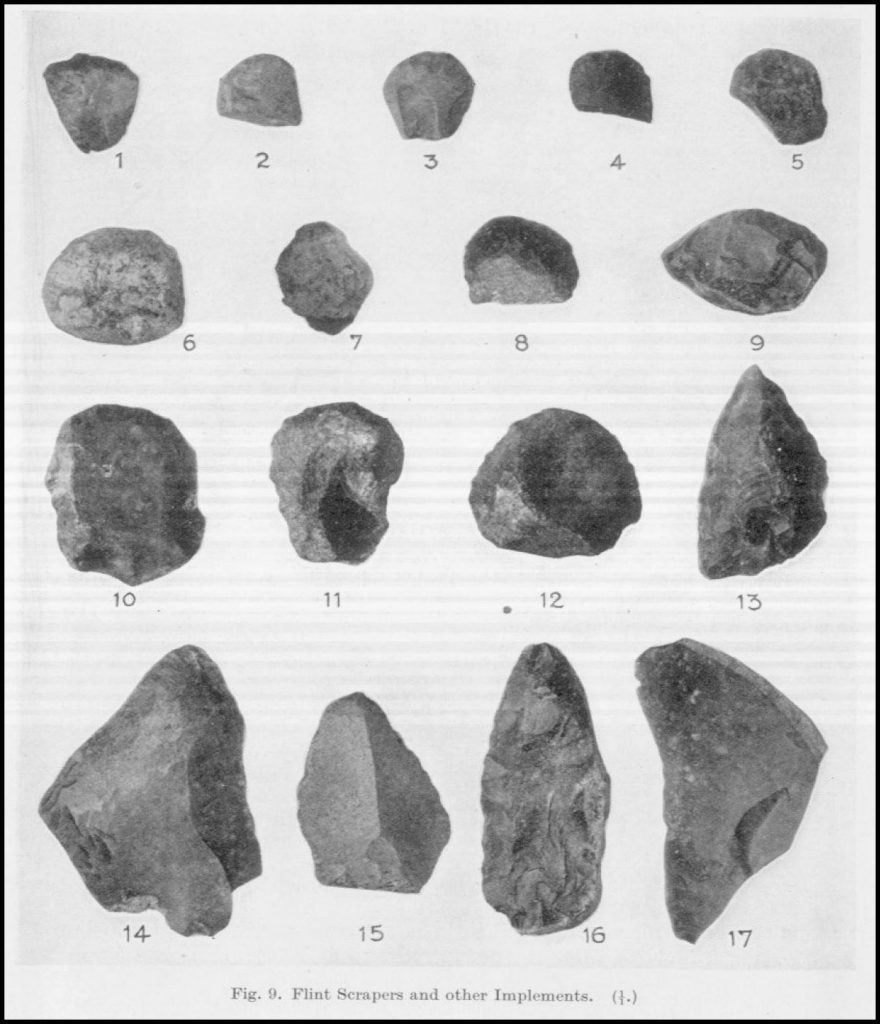

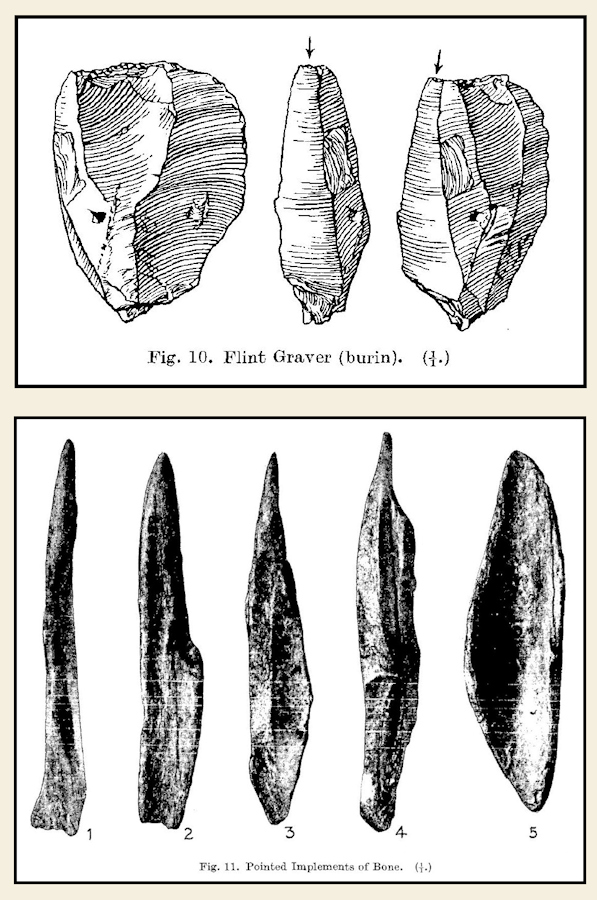

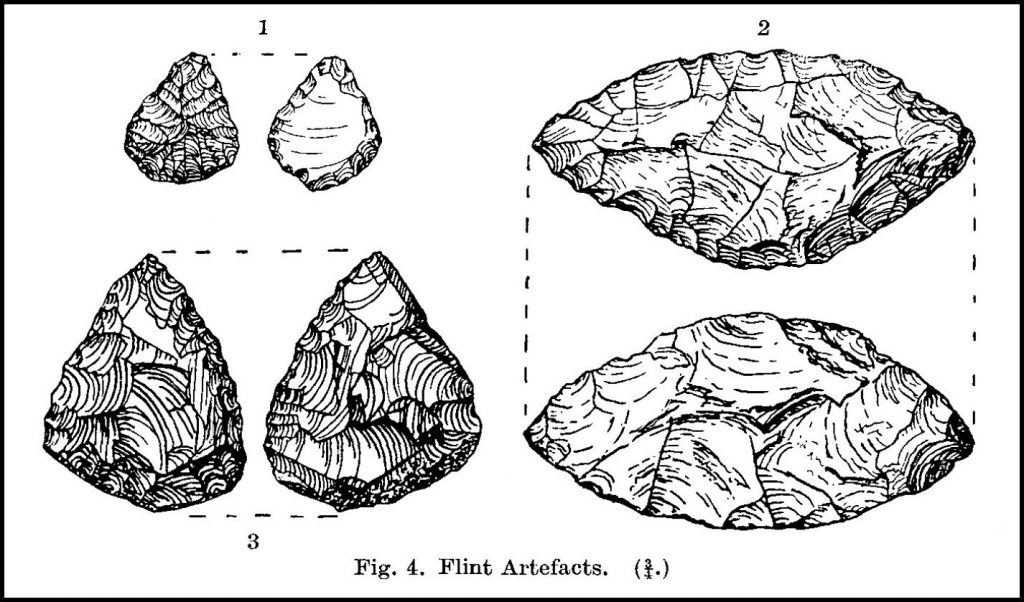

The Upper Chamber had suffered so much disturbance that very little of its original furniture survived. But two flint implements, found on the floor, may be regarded as remains of the primary grave-goods. Fig. 4, 1, is a leaf-shaped arrow-head, broken at the point, and now 2 cm. long. It is worked on both faces, but only along the edges on the bulbar face. Both surfaces are mottled with an irregular white patina.

Fig. 4, 2, is a thick leaf-shaped point, 4 cm. long, made of unpatinated black flint, trimmed on both faces. One edge has been straightened out as a result of the removal of a small facet from the point. This flake, though resembling a graver facet in the manner of its detachment, has not left a graver edge and may not have been intentional. Along the base, part of the crust of the original nodule has been left on one face.

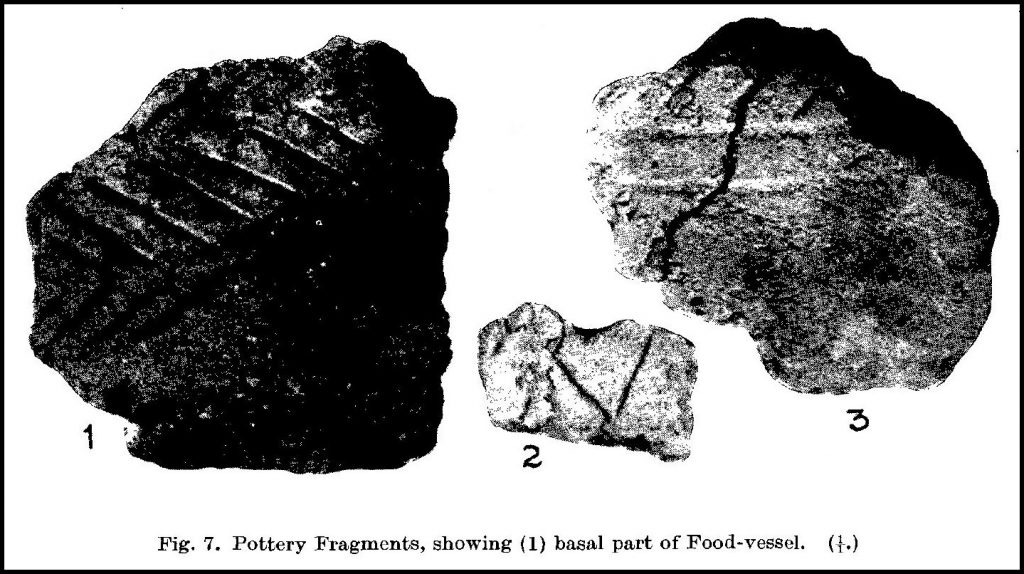

A third implement, fig. 4, 3, of yellowish chert, though found on the top of the broken-down wall of the eastern cell about 2 feet back from the face, may also pass as original. The bulbar face shows a number of broad, shallow, thinning flakes; the outer surface is trimmed only along the two edges. In a general way the implement is comparable to the flint knives from the stalled cairns of Midhowe and Yarso

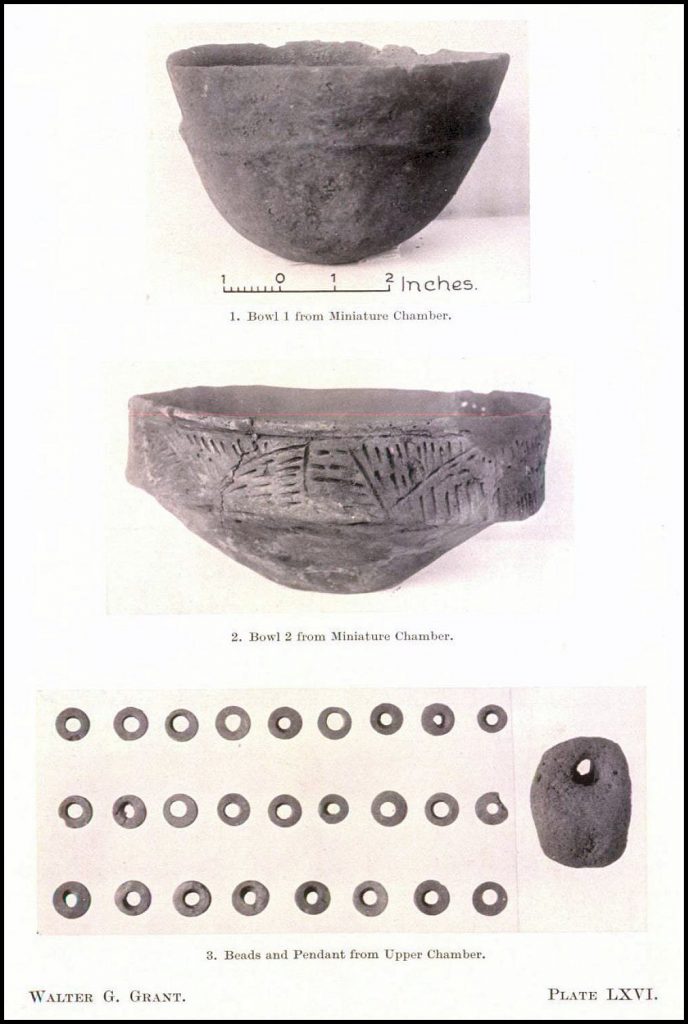

Near the inner end of the entrance passage, under blocking stones but 9 to 12 inches above the floor, were found 35 disc beads of greyish flagstone and a perforated pendant of pumice (Pl. LXVI, 3). These are the first stone beads to be recorded from a Neolithic chamber in Scotland, but after all do not differ essentially in form from the disc beads of “jet,” frequently found in Early Bronze Age graves, including the cist built in the chamber of the long horned cairn of Yarrows in Caithness. The pumice pendant, 2.8 cm. long, 2.1 cm. wide, and 1.2 cm. thick, is also unique. The possibility cannot be excluded that the beads and pendant belong to the furniture of secondary interments in, or contemporary with, the “three stone kists” mentioned by Lady Burroughs.

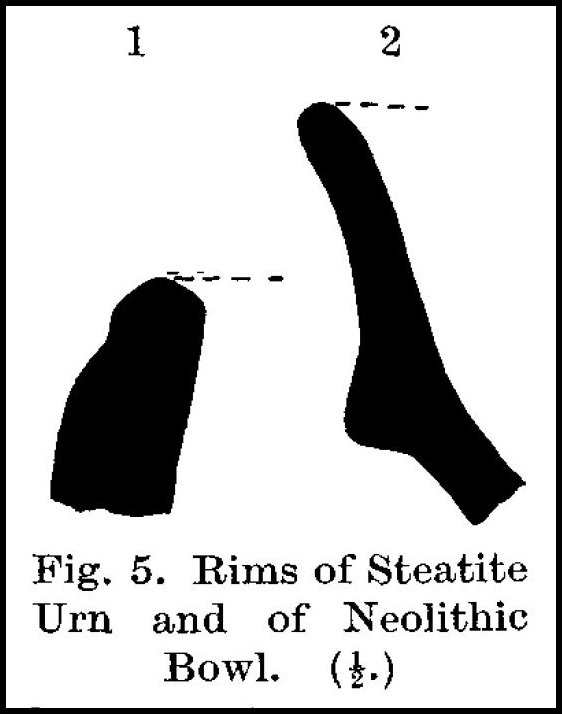

A like suspicion applies in a still higher degree to some sherds found outside the door of the upper chamber. They are reddish in colour, and contain large grits and include part of a flat base and of a rim, possibly false. The flat-bottomed urn to which all presumably belong seems to have been built up in rings and bears a general resemblance to domestic pots, usually termed Iron Age in Orkney, but is not far removed from some of the thinner vessels from Rinyo. Finally, from a dump of material presumably removed by General Burroughs from the upper chamber come a calcined scraper on a split round nodule of flint, half a similar scraper not certainly calcined, and two rim fragments of a steatite bowl with a groove below the rim (fig. 5, 1, below). Two shoulder-blades of oxen were also found in the entrance passage.

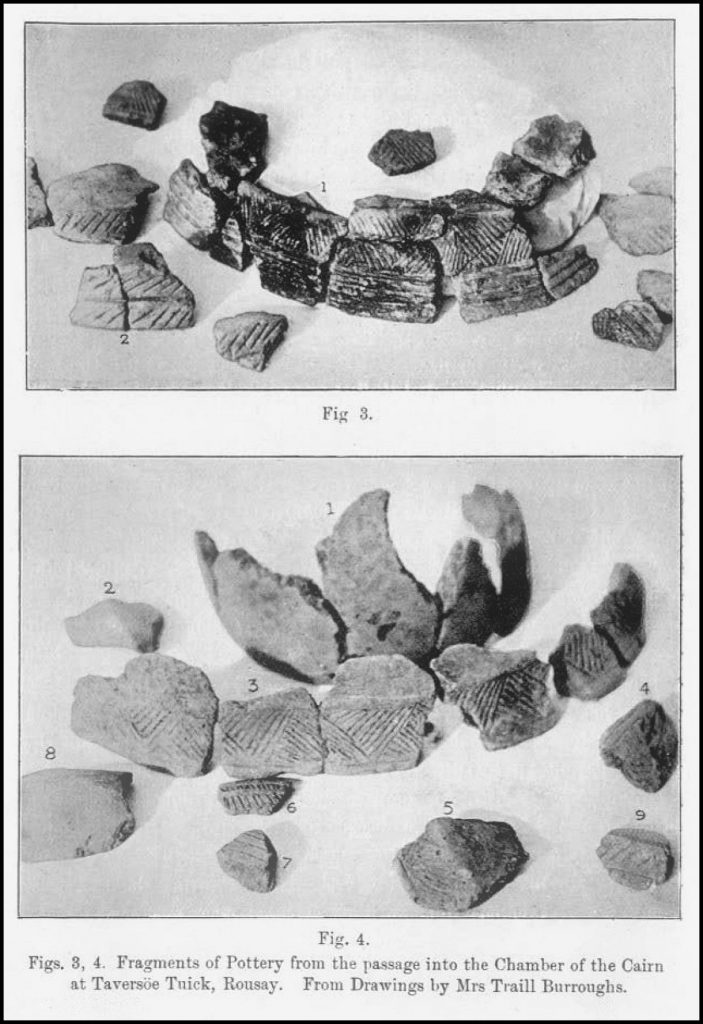

From the Lower Chamber fragments of at least three urns and part of a human jaw-bone were recovered on removing one of the benches. All the recognisable fragments belong to carinated bowls of the familiar Unstan type. One is undecorated, but burnished, tool marks being visible on the surface (fig. 5, 2). The rim is thinned and slightly everted, giving a faint hint of kinship with the “Yorkshire bowls.” A second is decorated with oblique incisions alternating in the usual Unstan manner. On the third only two grooves parallel to the rim can be seen; it may well belong to the same urn as the fragment collected by General Burroughs and illustrated in Proceedings, vol. lxv. p. 88, fig. 11, 1. Even so, adding the new rim fragments to those there illustrated, it appears that at least sixteen urns must have been included in the original furniture of this chamber.

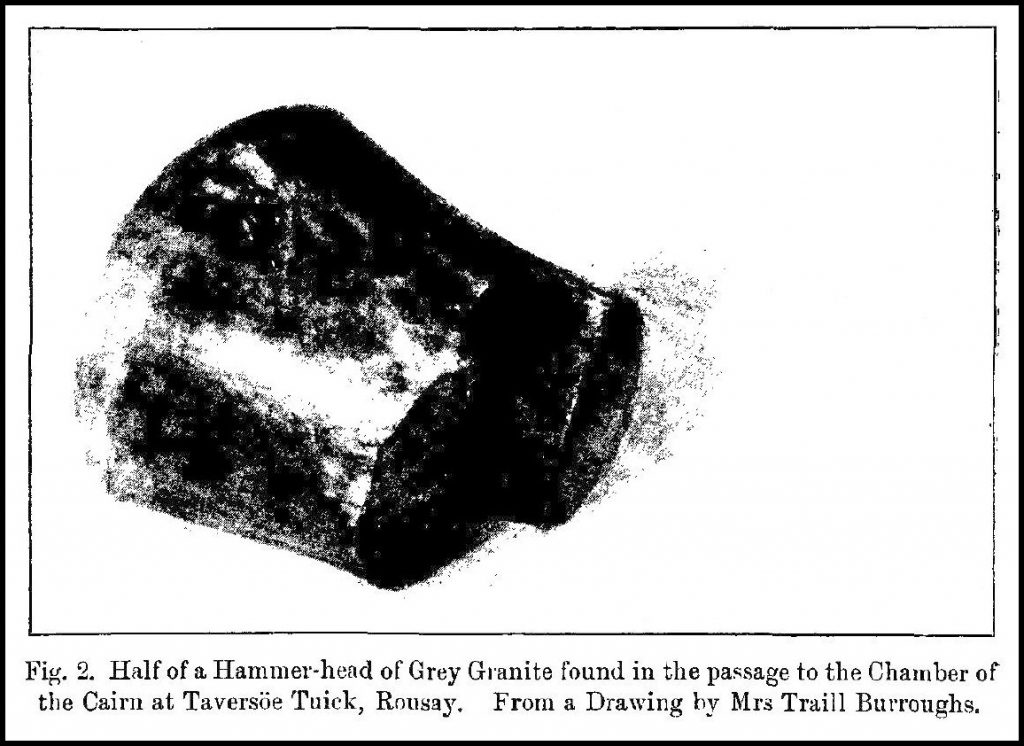

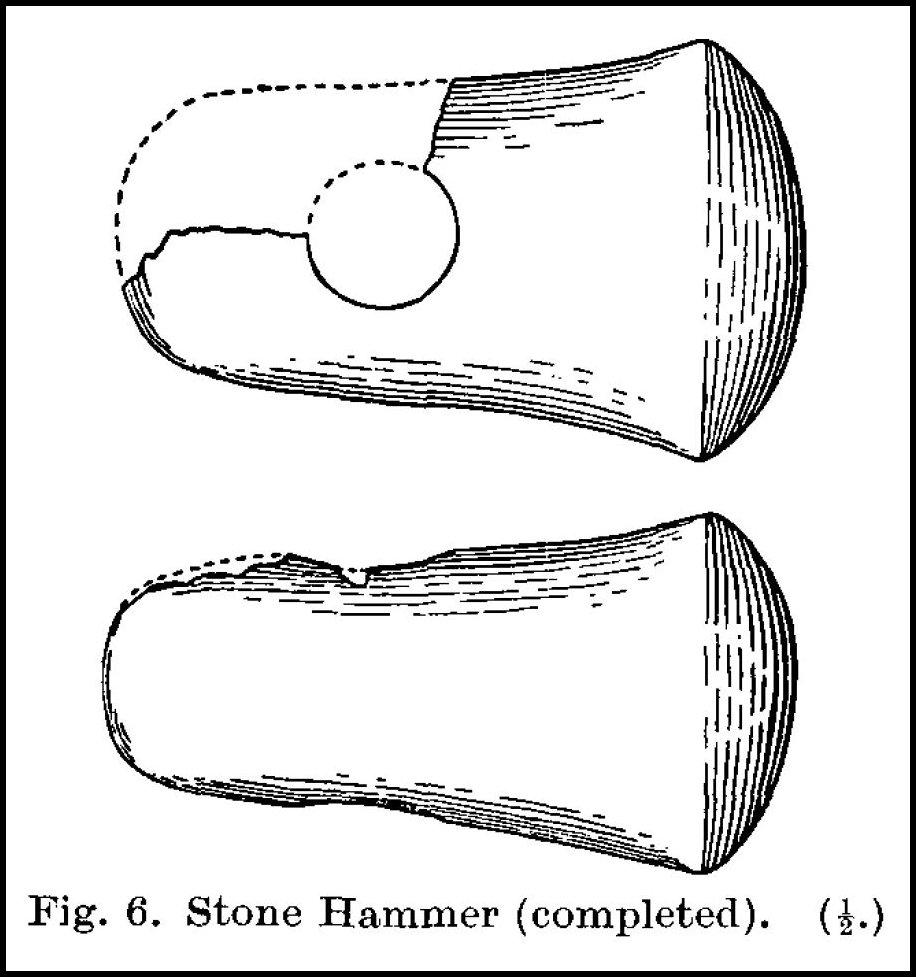

A further fragment of the stone hammer, previously recovered from the passage into the chamber just outside the “ barrier,” was found on the dump from the General’s operations, and permits of a restoration of the whole weapon (fig. 6). It shows that while the end first recovered expands like the butt of a Continental battle-axe, the opposite end neither expanded nor tapered to a blade, but finished up rather in the manner appropriate to the commoner pestle-shaped mace-heads.

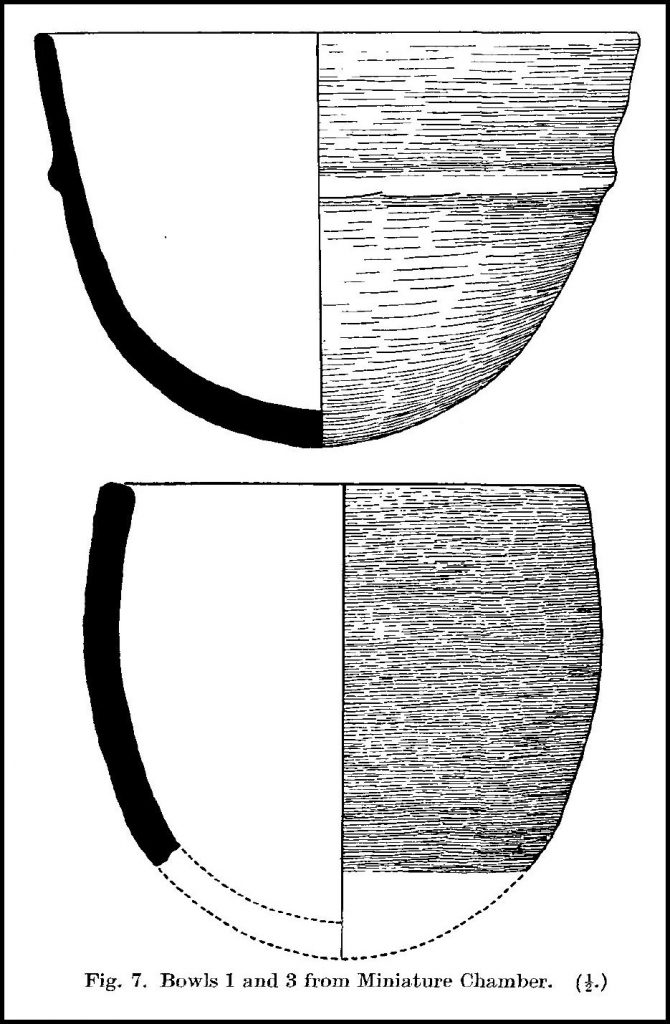

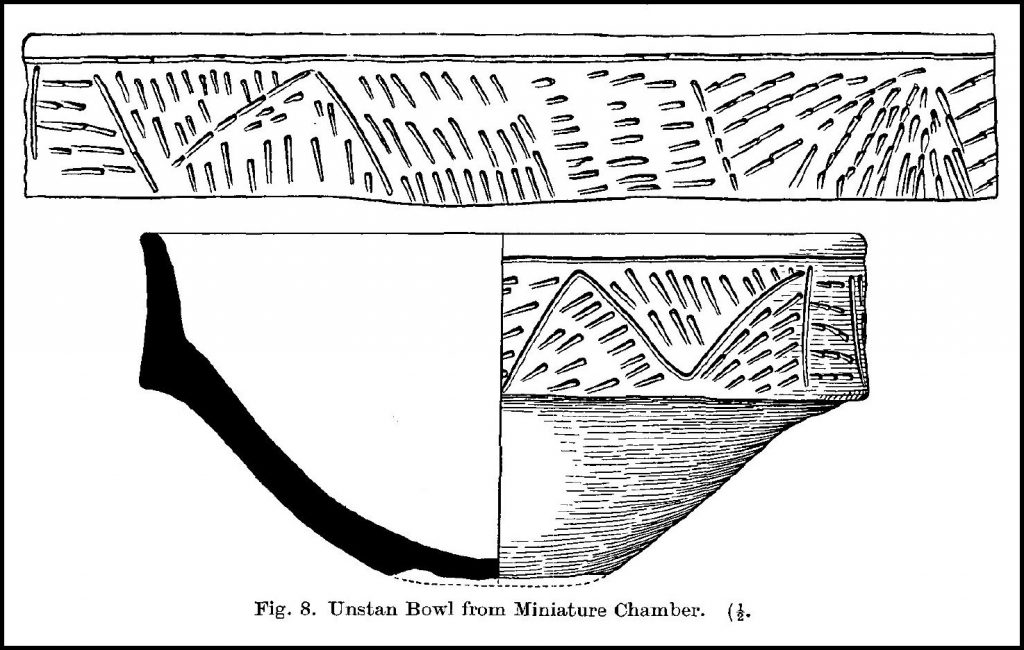

The Miniature Chamber outside the cairn contained two complete vases, while parts of two others were found, one in its entrance. No. 1 is a complete bowl of dark brown to black ware, with a corky appearance due to the decomposition of the grit temper. It is 15.7 cm. in diameter at the mouth and 10.3 cm. deep, the walls being 5 mm. to 9 mm. thick. An applied moulding runs right round the vase, giving the effect of a carination. The vase thus represents type D in Piggott’s classification of British Neolithic pot-forms. This form was hitherto unknown in Scotland. Vessels of the same general shape but substantially deeper and decorated in the Beacharra style proper to South-Western Scotland and Northern Ireland do indeed come from Clettraval, North Uist. But closer parallels can be found in Southern England. No. 2 is a typical carinated bowl of Unstan type, 19.5 cm. in diameter and 9 cm. deep. The neck is nearly vertical, the base sags heavily at the centre, precisely as in the bowl from the long stall cairn at Midhowe, Rousay. The neck is decorated with a single zone of patterns varying in panels. The zone is bounded above by a continuous incised line, and similar lines, either oblique or vertical, separate the panels. These incisions have been executed with a square-ended tool. The panels are mostly filled in with long stab-marks, made with the same tool and arranged in varying directions. Only in one panel are the stabs joined by “drags” to form continuous lines as in the classical Unstan decoration. No. 3, found at floor-level in the entrance, is part of a plain baggy pot of Piggott’s form B, probably 13.5 cm. in diameter at the mouth and more than 10 cm. deep. The rim is plain, and no trace survives of the lugs usually attached to vases of this shape. No. 4, found in the entrance, represents part of a keeled bowl without any decoration.

The group of vases from this intact chamber establishes the co-existence of typically North Scottish (Orcadian) Unstan bowls with classic forms of the Windmill Hill or British Neolithic A ceramic series. To this extent it justifies the contention that the culture of the chambered tombs of Orkney is a specialised variant of the more generalised Neolithic culture of these islands.

Extracted from

The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Volume 73, pp. 155-166 1938-39

Available in the Orkney Room at Orkney Library & Archive