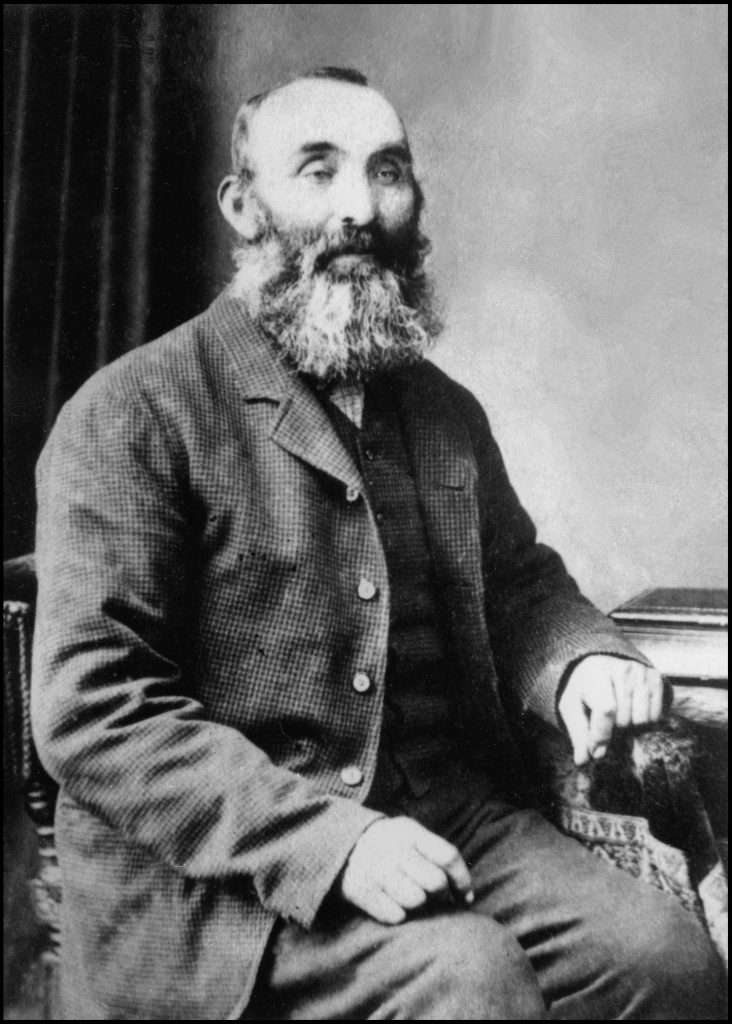

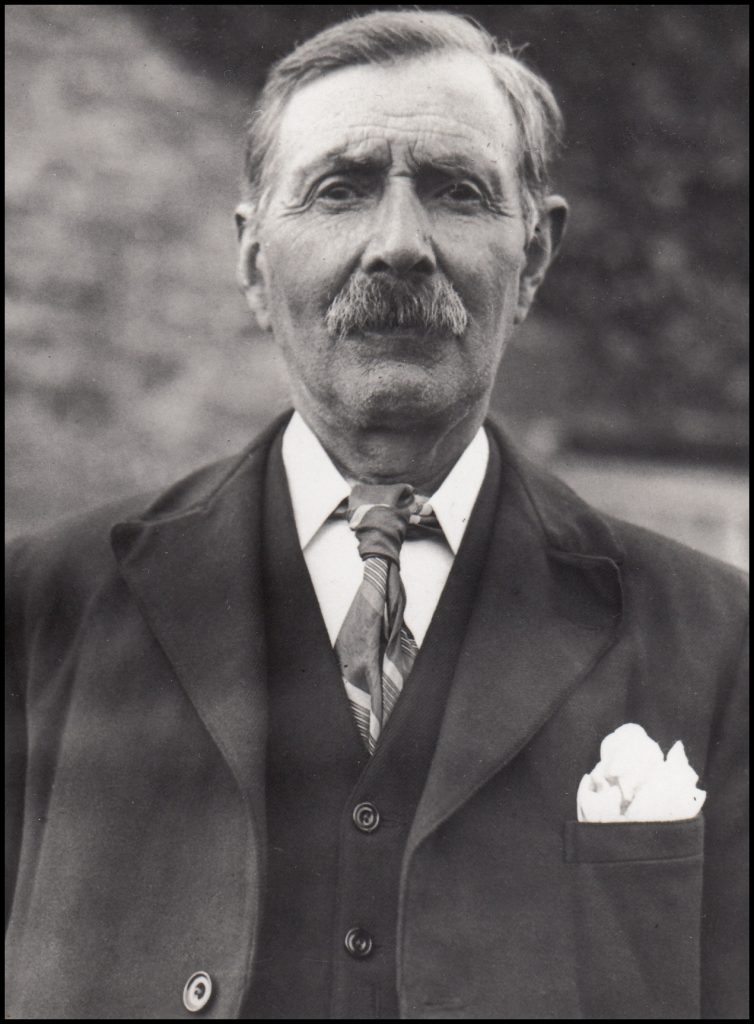

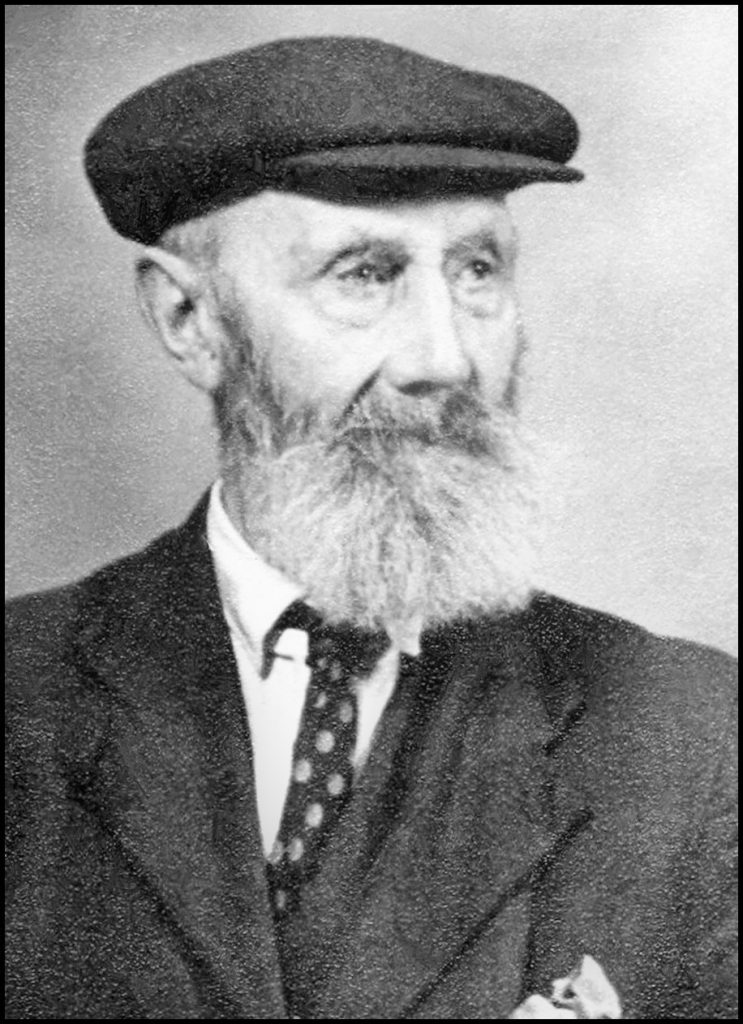

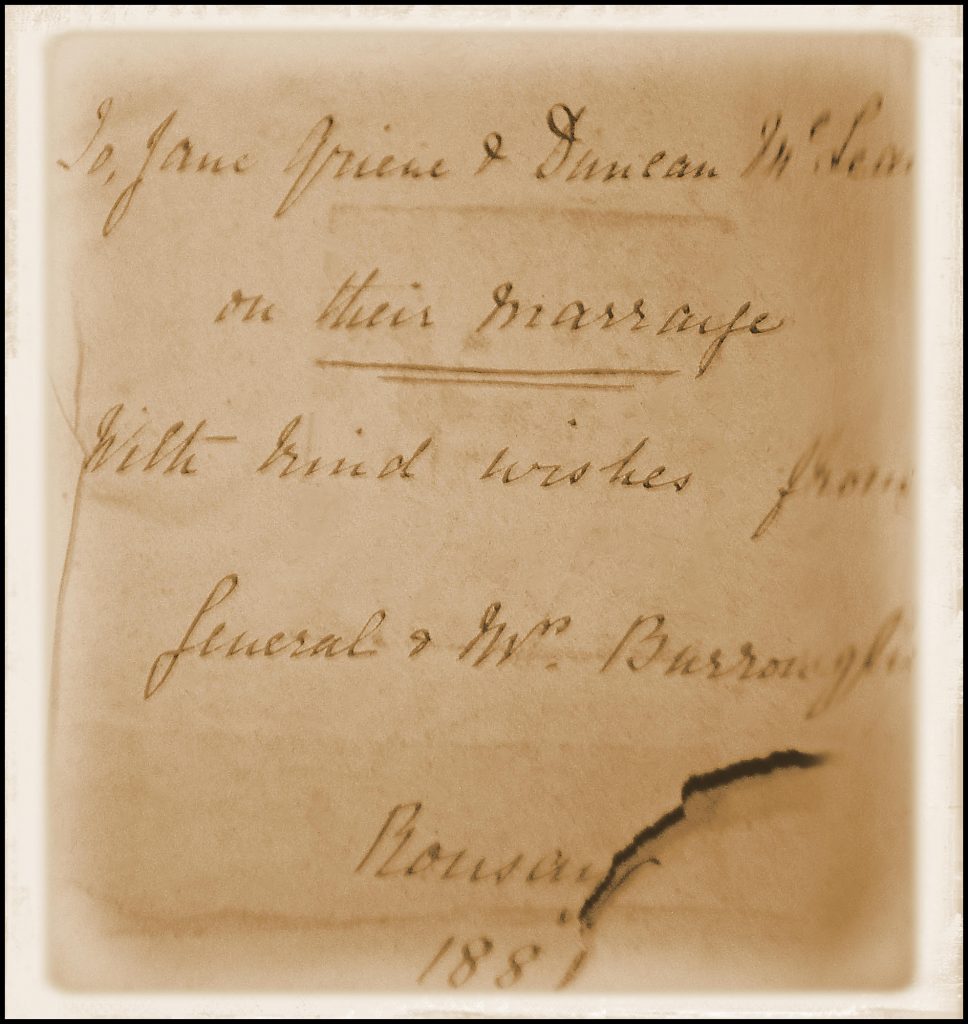

In his book The Little General and the Rousay Crofters, William P L Thomson tells of estate regulations in general making no mention of mining or quarrying. In 1881, the laird, Frederick William Traill Burroughs, was optimistic about the mineral potential of his Rousay estate, so a clause was added to the regulations reserving the right of the landlord to open a mine or quarry on a tenant’s land. Later a second clause was added prohibiting mining or quarrying by tenants.

The Crofters Act with its explicit reserving of mineral rights to the landlord coincided with Burroughs’ interest in mining ventures and it was perhaps not surprising that he saw his rights under the Act as a weapon he could use against his enemies. There was a further reason for his action. Estate regulations had previously required crofters to obtain the proprietor’s permission for any new building they intended to erect but, under the Act, this was no longer required. Burroughs was incensed that crofters who had recently been pleading poverty should now be busily engaged in putting up new buildings over which he had no control. On an estate liable to rack-renting, it was never wise that a croft should appear more conspicuously prosperous than its neighbours, and tenants-at-will had hitherto been unwilling to invest in a doubtful future. The new security, however, had unleashed a flurry of building activity.

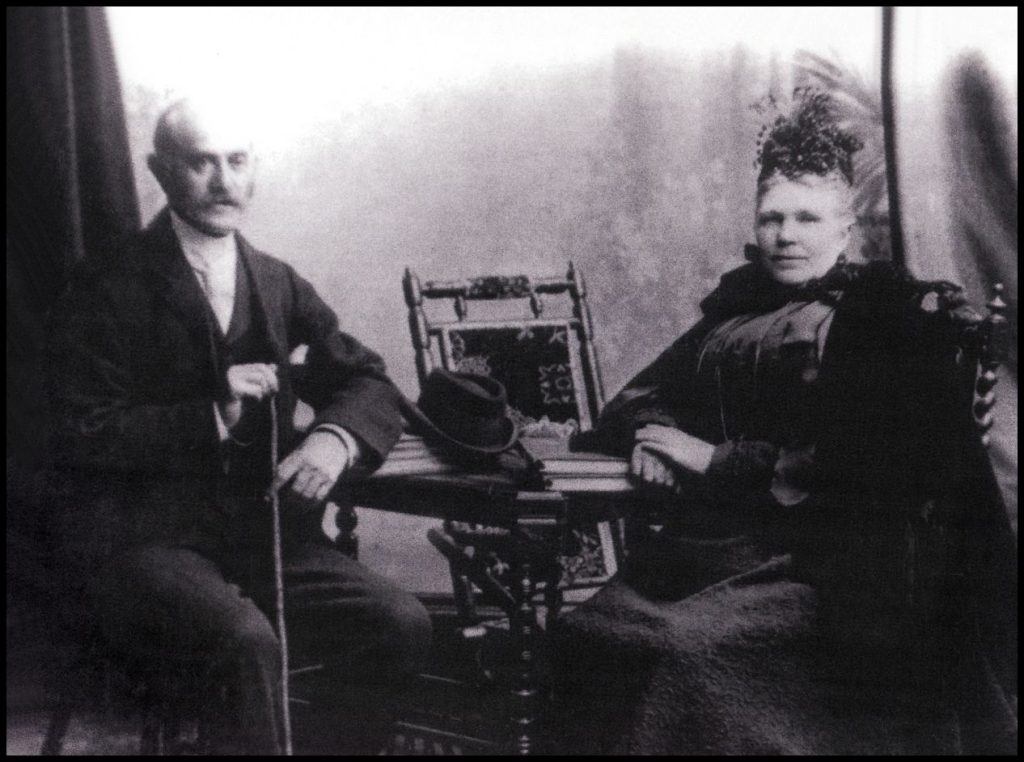

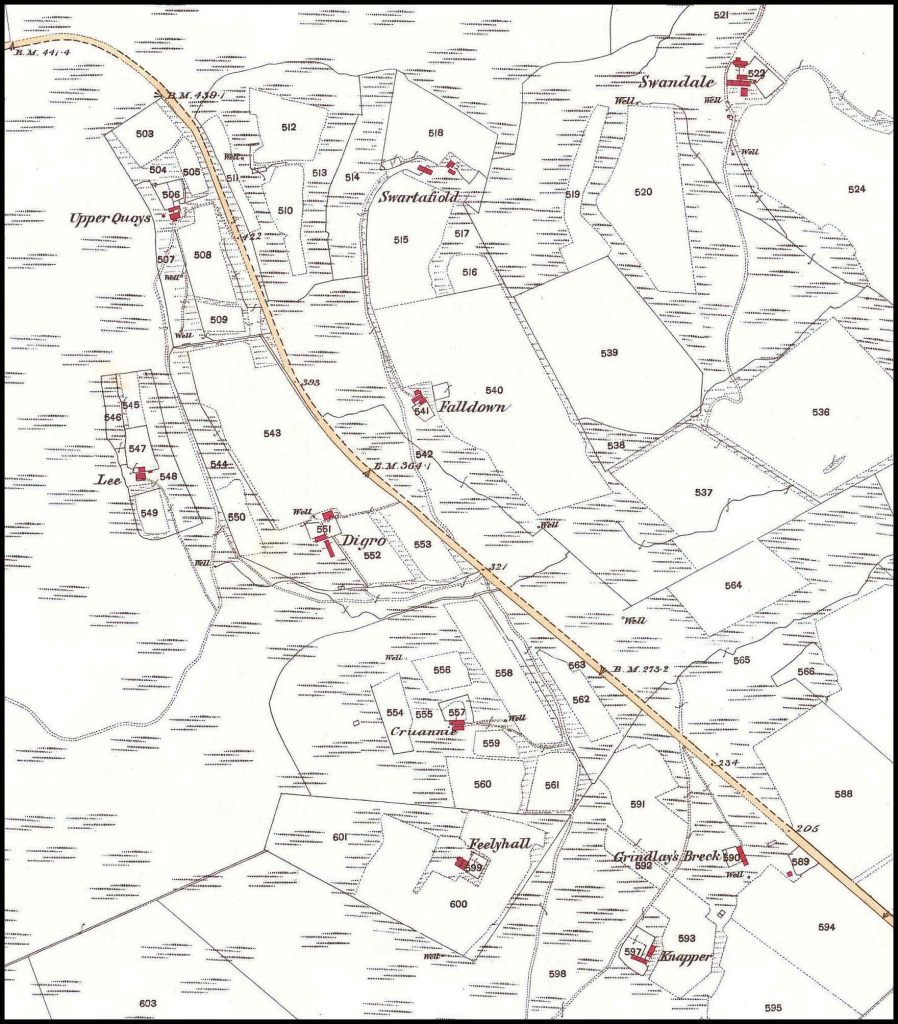

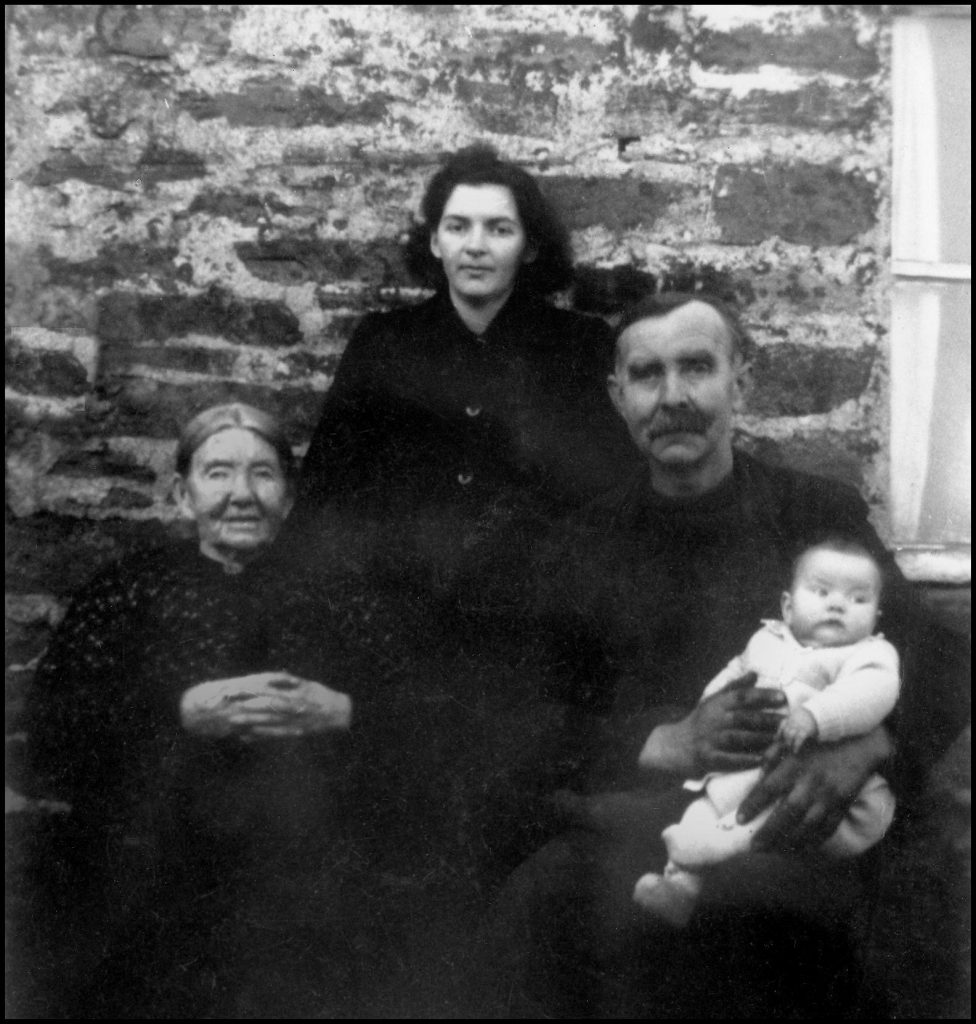

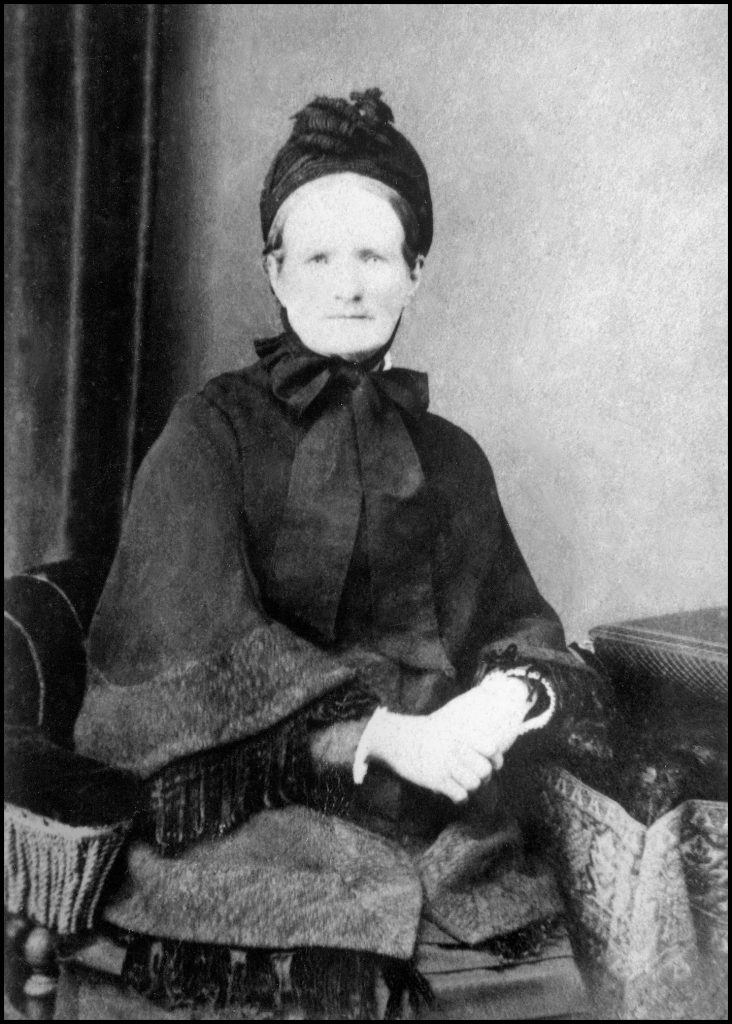

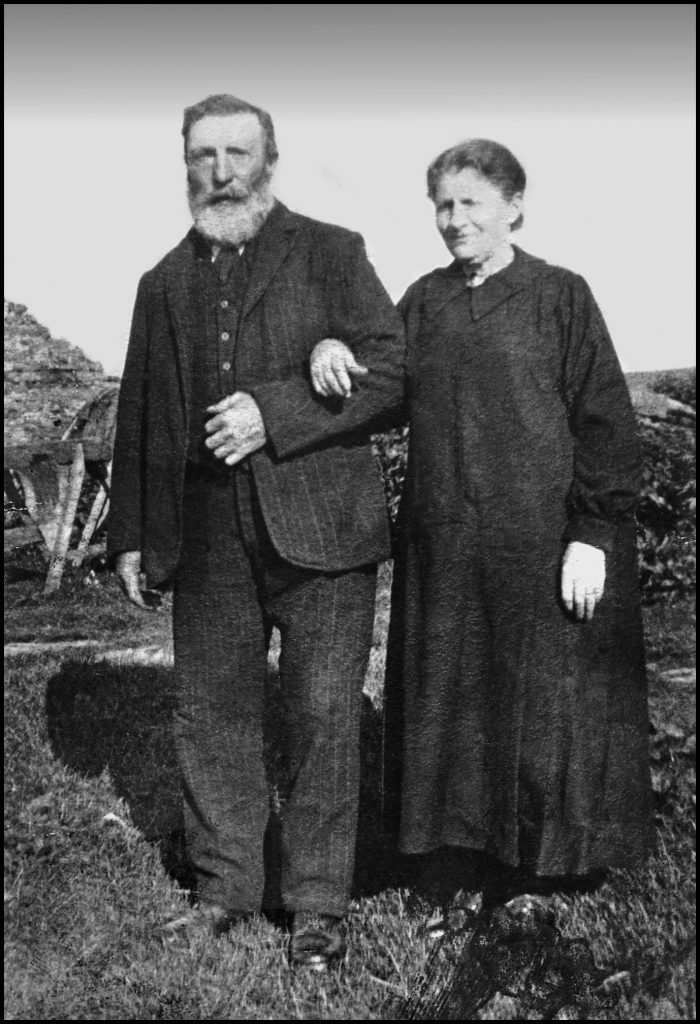

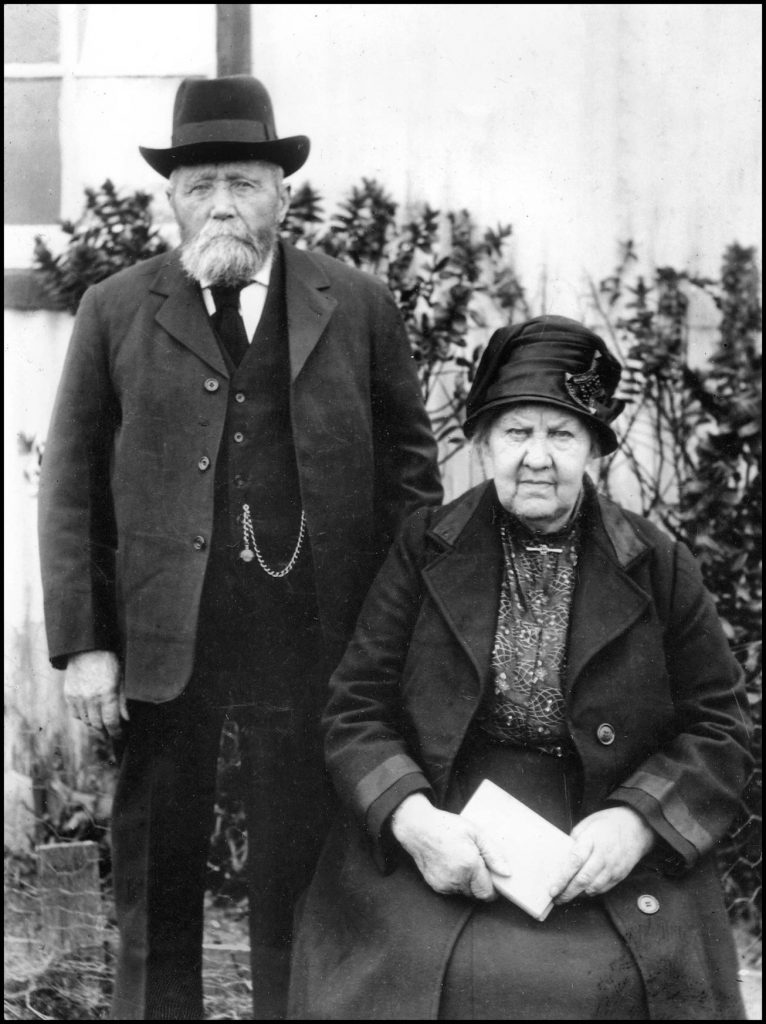

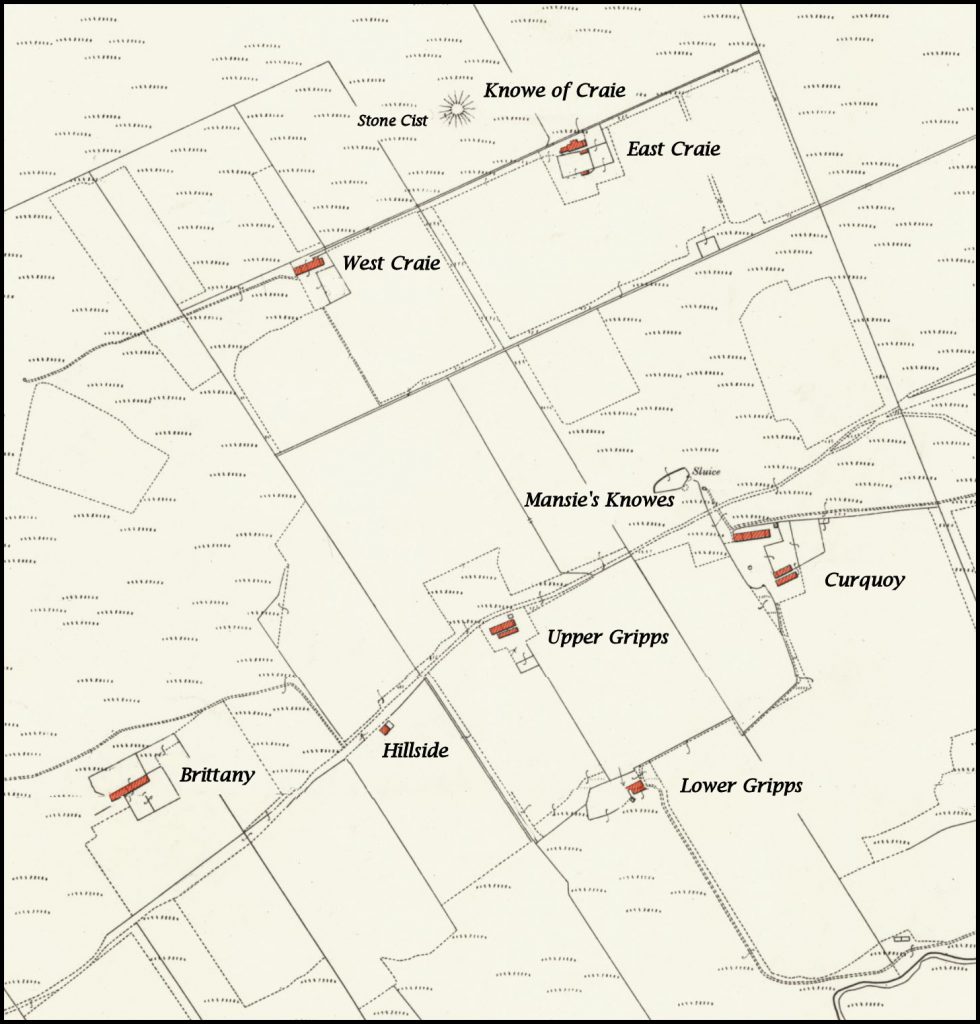

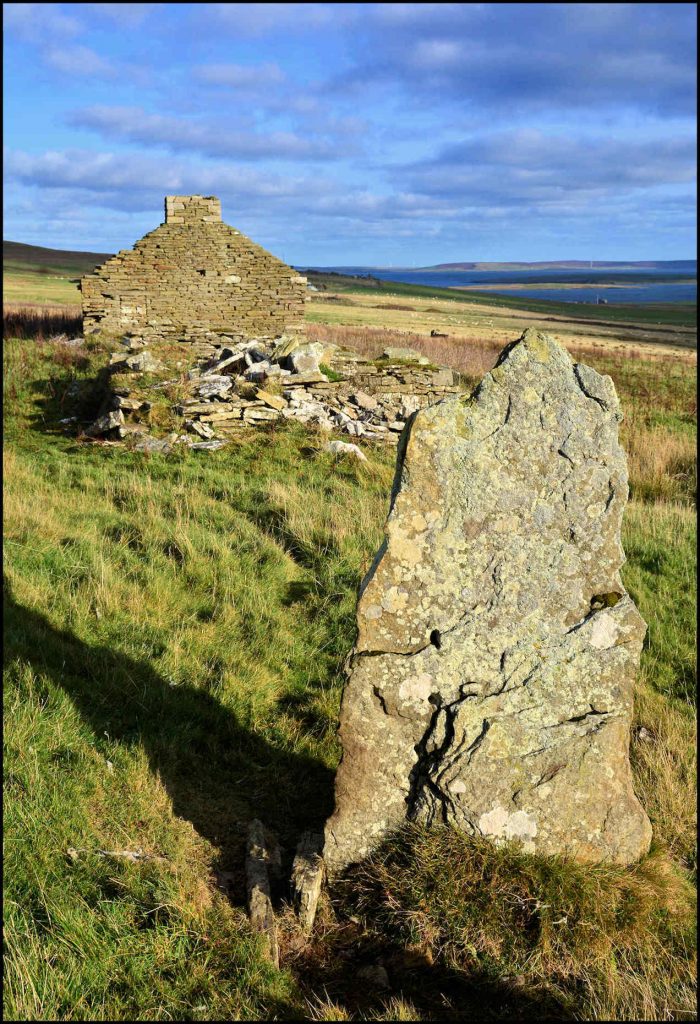

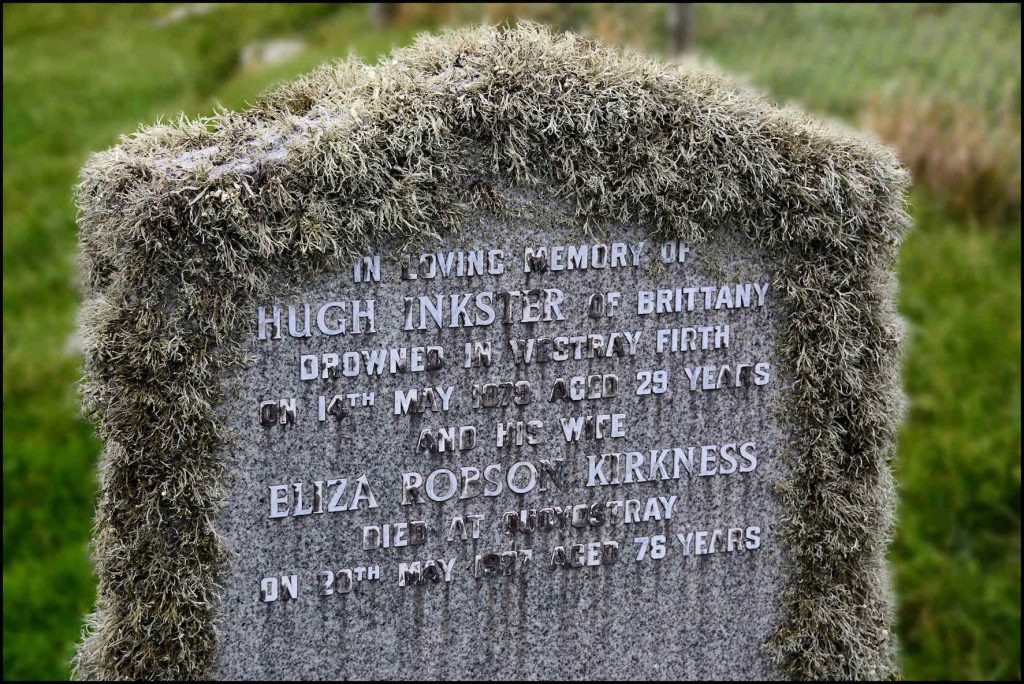

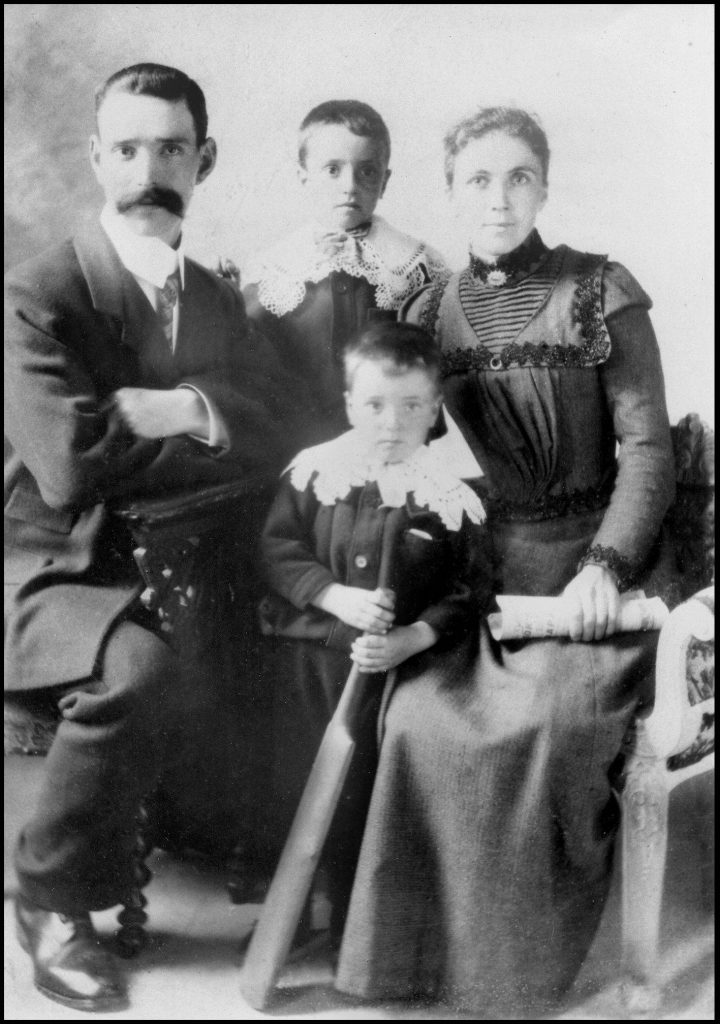

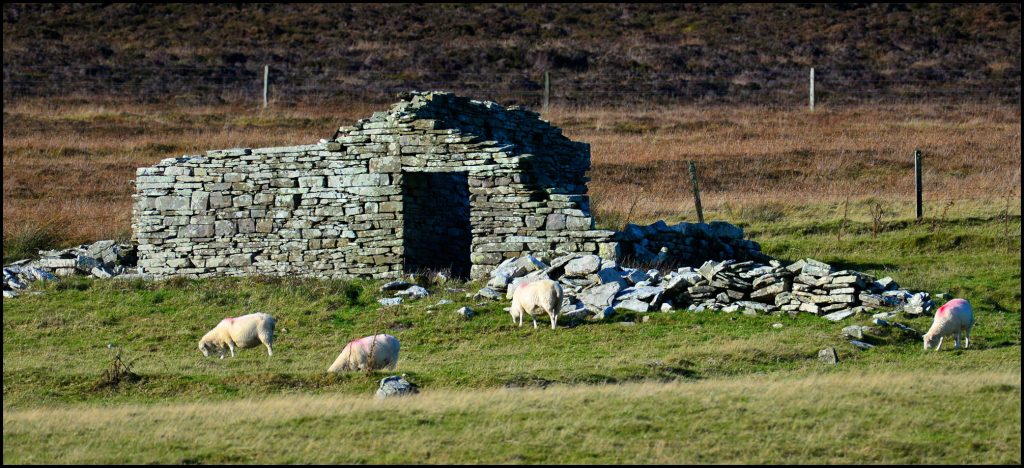

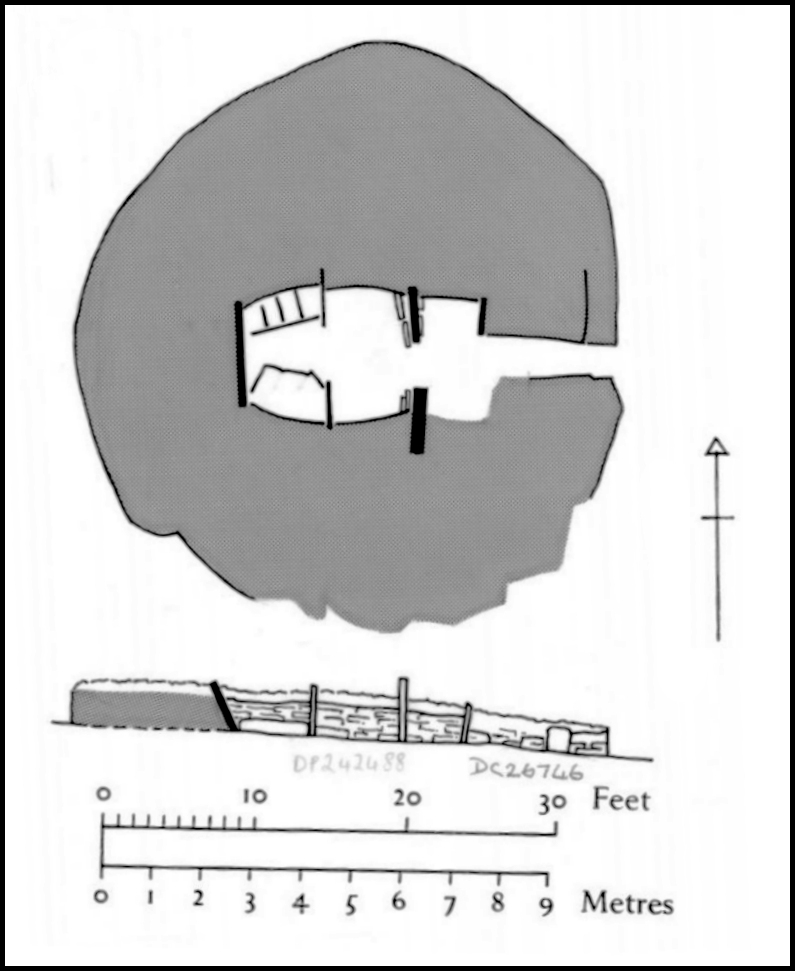

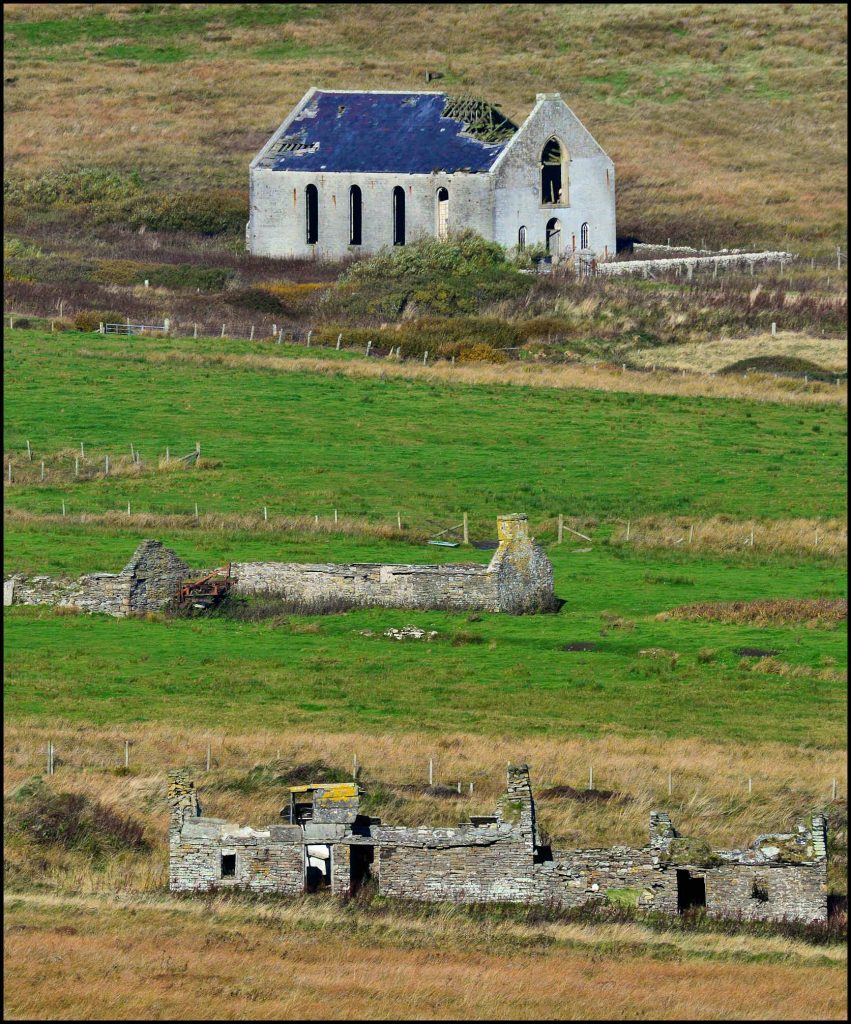

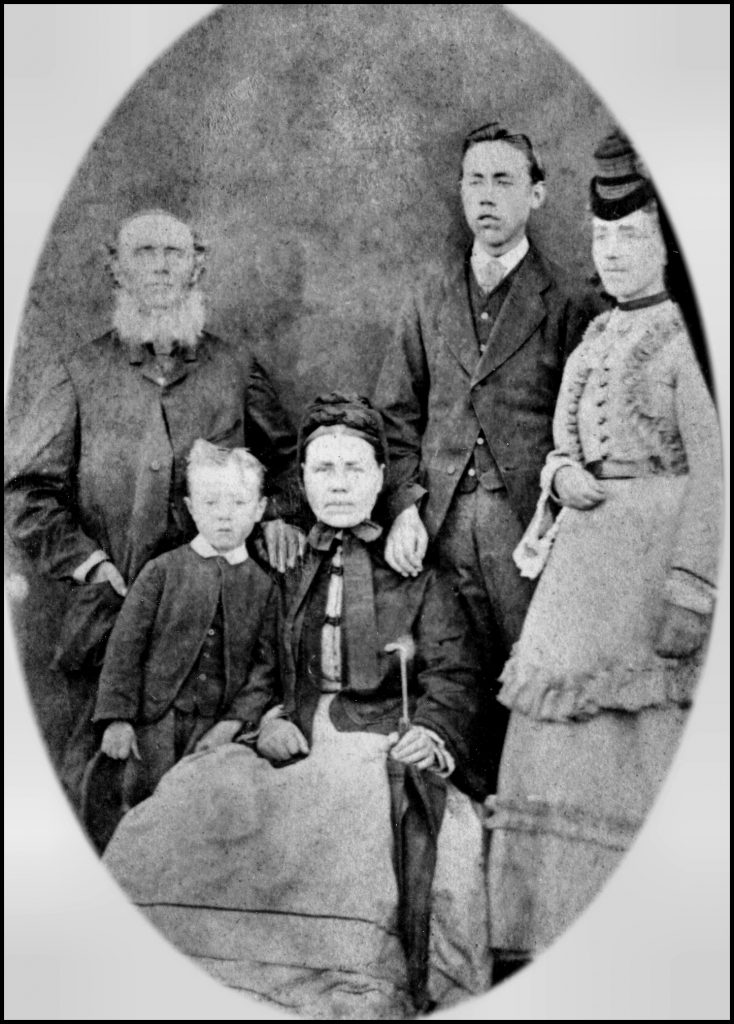

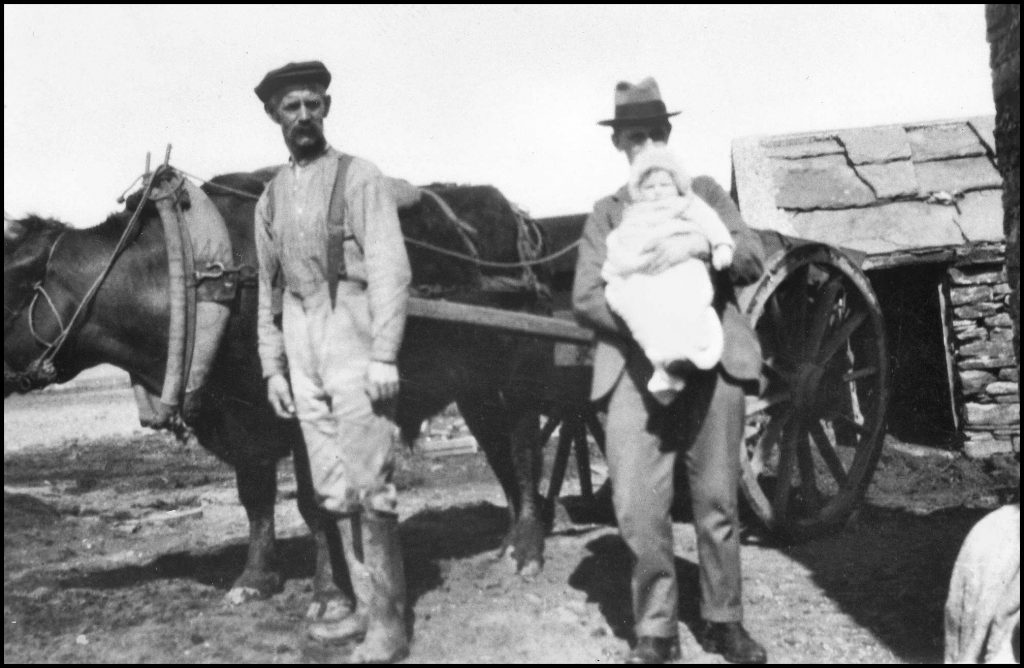

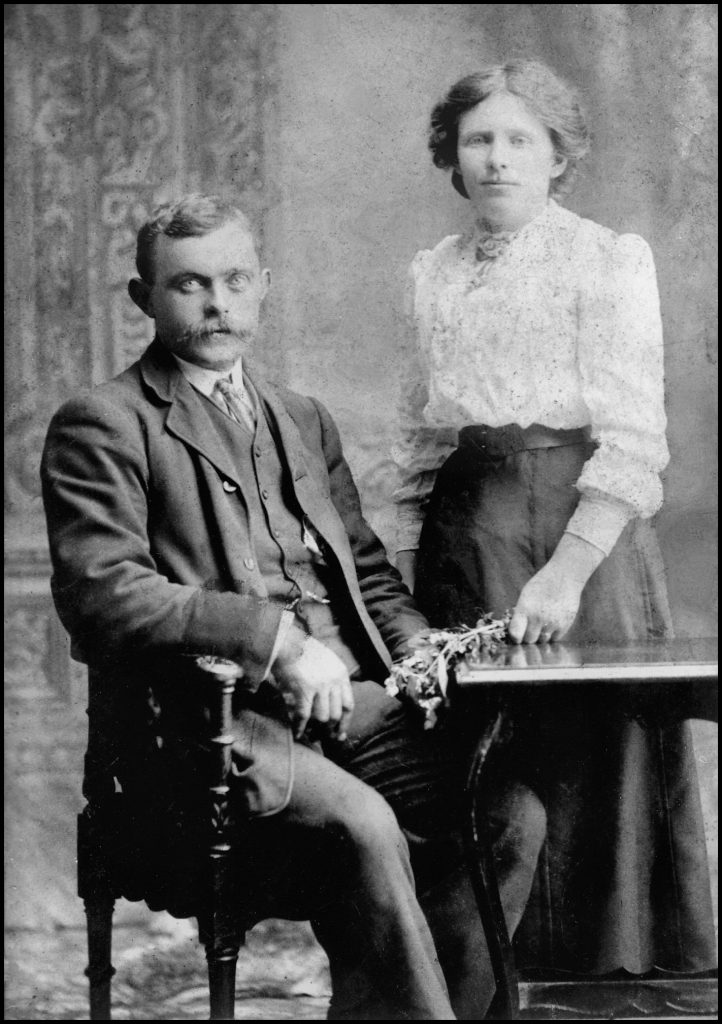

The matter came to a head over the re-roofing of a house occupied by Robert Inkster, a seventy-six-year old crofter living at Swartifield in Sourin. Both house and barn had stood unaltered for forty years and both were in a very poor state. In the summer of 1890 Inkster and his sixty-four-year old wife Mary Leonard of Digro, took up residence in the barn, With the help of a relative, he stripped the old flagstone roof from the house and set about the work of repair. He had not consulted Burroughs about his intentions and indeed had no legal obligation to do so. The laird first heard about the repairs in a report of what he described as ‘a triumphal procession of some ten carts’ taking stone from a quarry to the house site. Although estate regulations had for some years forbidden quarrying, this clause, like a number of others, had not been enforced and tenants had always been in the habit of opening small quarries whenever they required stone. In Rousay good building stone was plentiful and seldom far below the surface. Burroughs, however, angrily resenting this display of independence, sent his ground officer to warn Inkster and, in a heated exchange, Inkster declared he would continue to take as much stone as he needed.

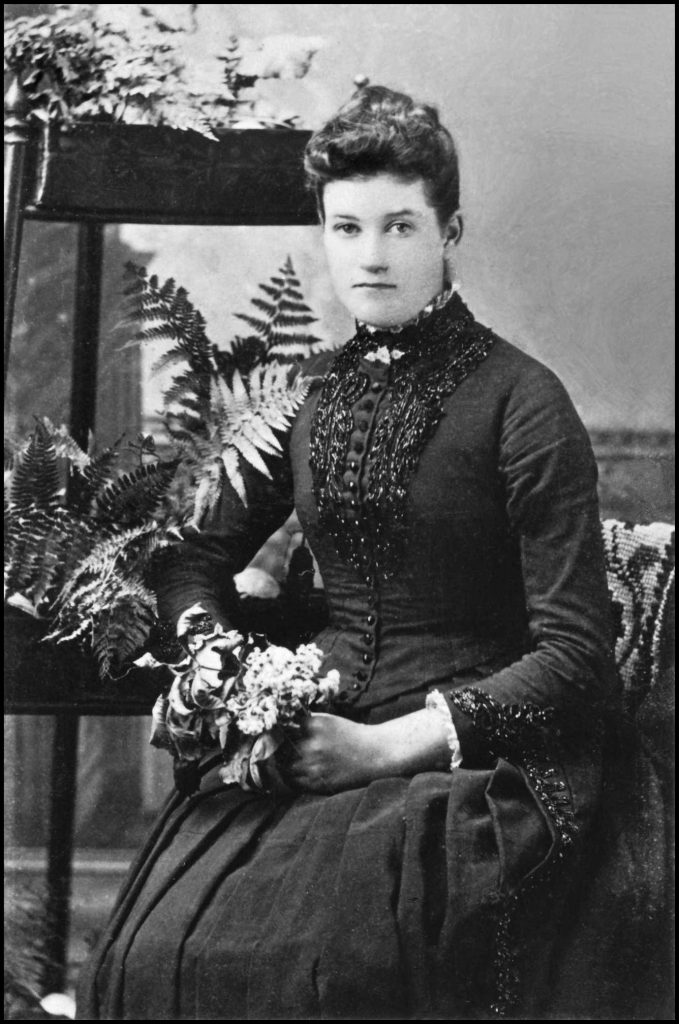

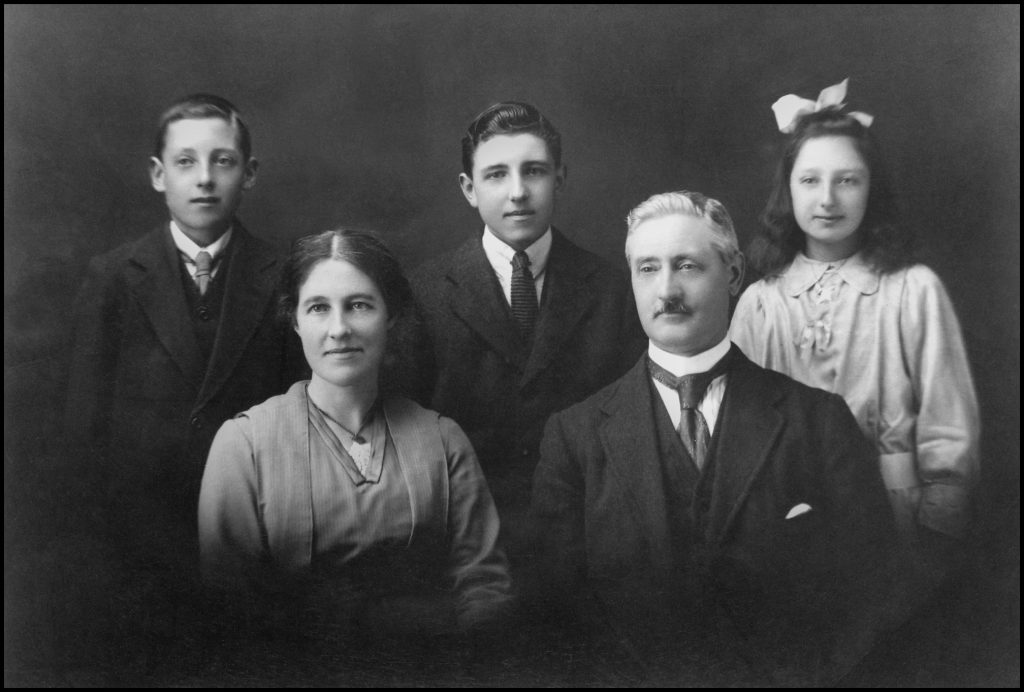

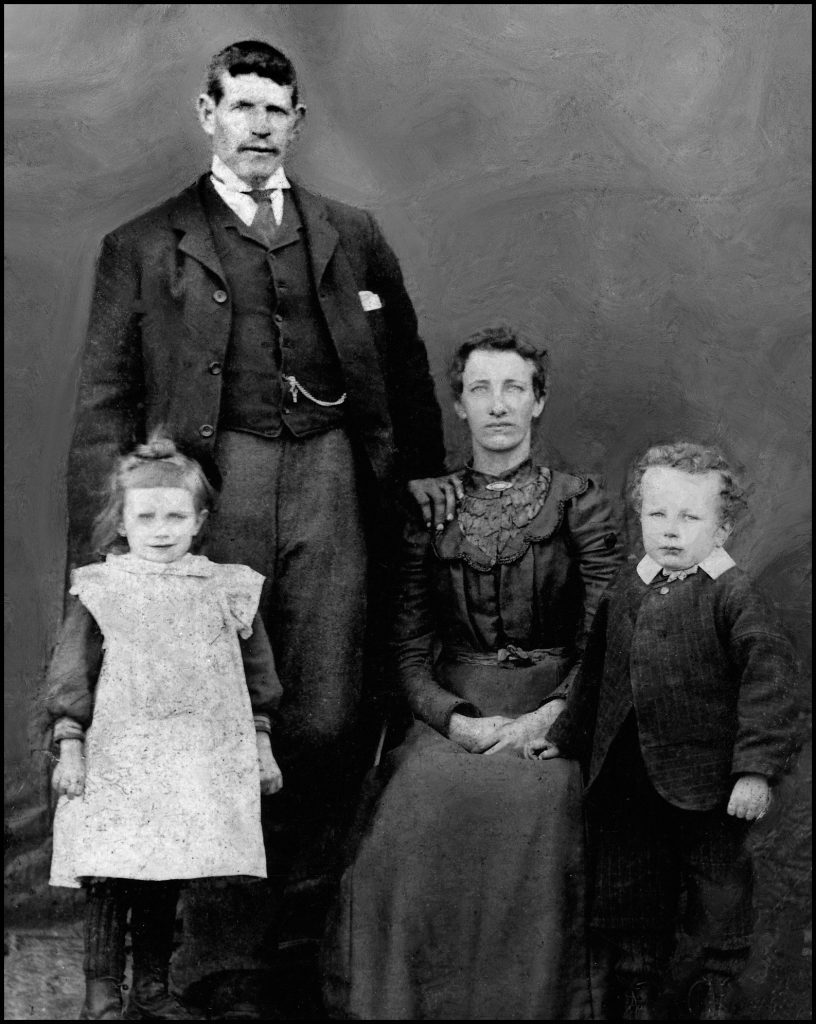

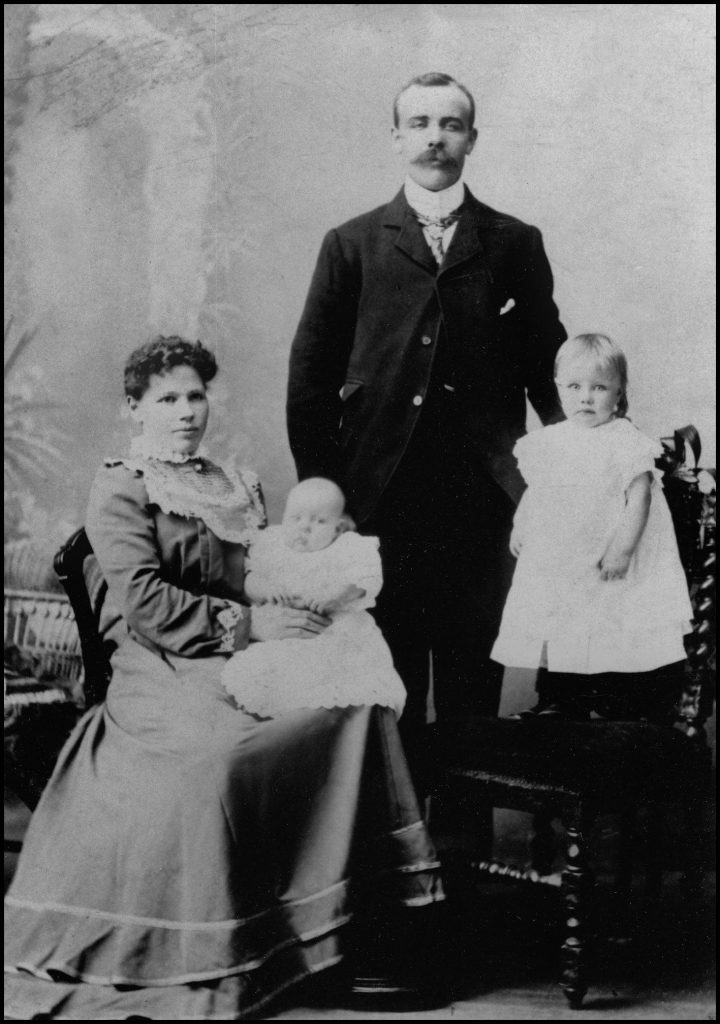

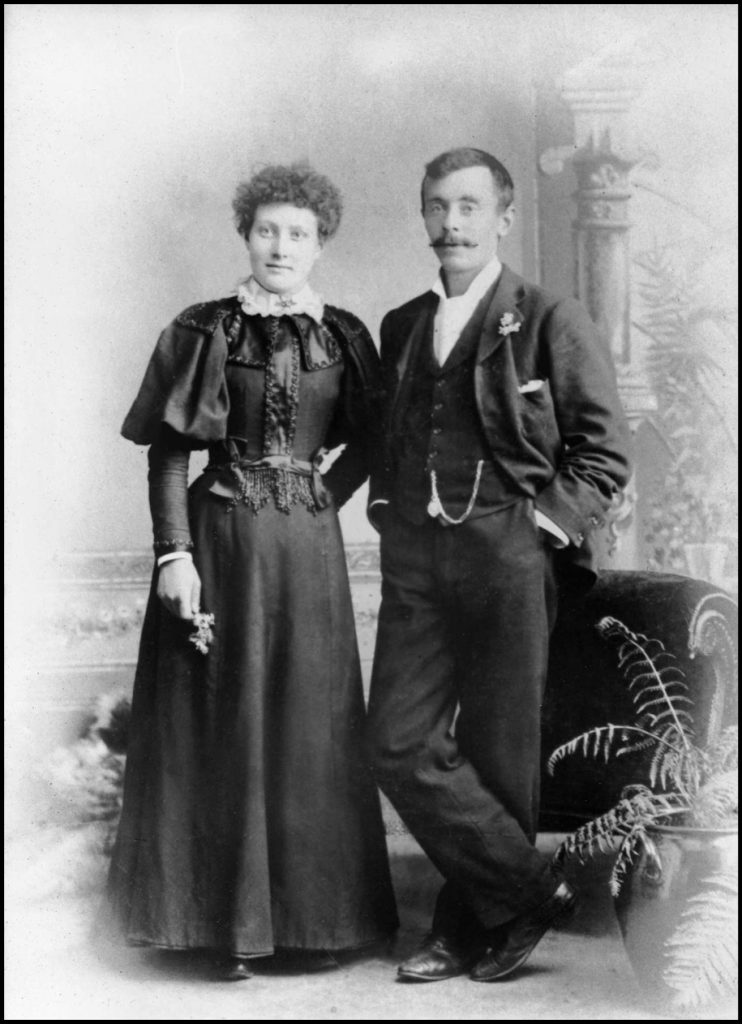

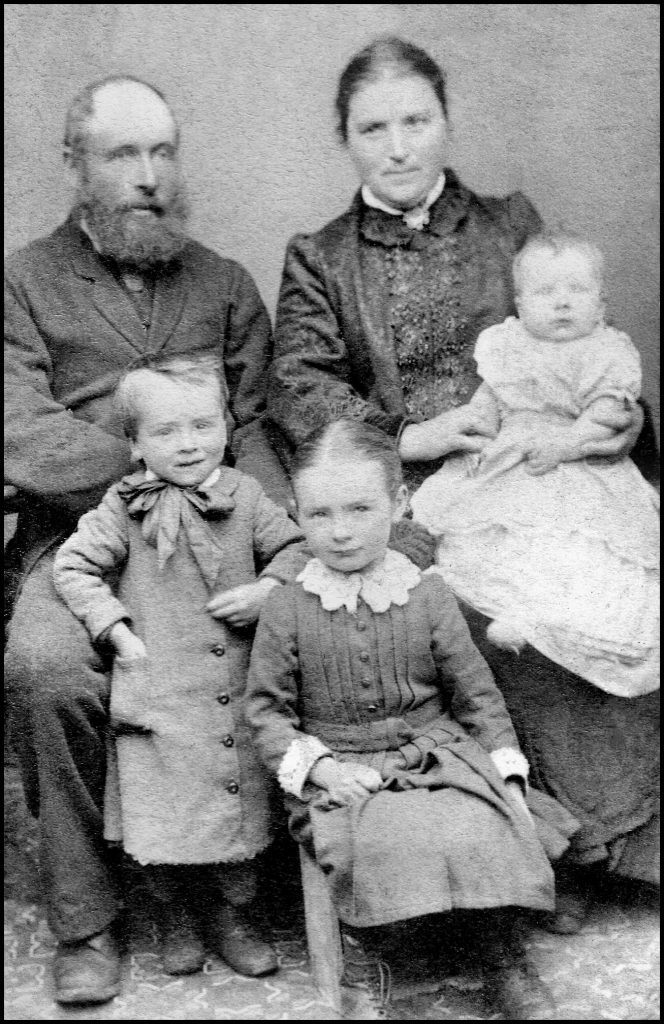

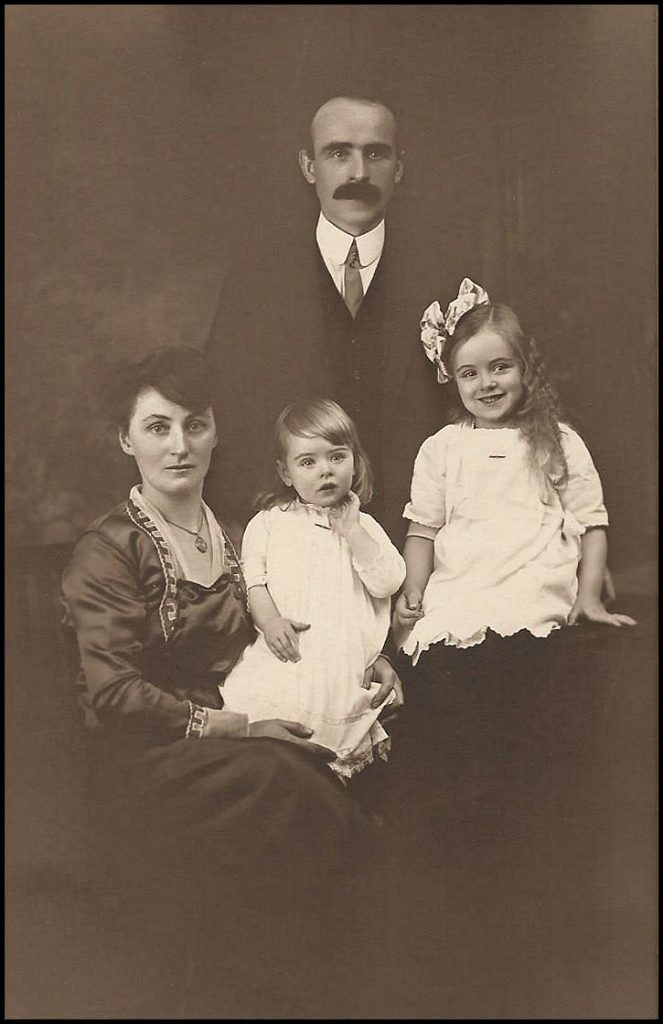

The laird’s next move was to have a lawyer’s letter sent to Inkster warning him that, unless he gave an undertaking that he would remove no more building stone, Burroughs would obtain a legal interdict against the ‘theft’ of his property. A similar letter was sent to Peter Yorston who was also improving the house and steading on his croft of Oldman in Sourin, where he lived with his wife Mary Kirkness and children Eliza, James, and John. The crofters immediately contacted Kirkwall lawyer Andrew Thomson who was again called on to defend Rousay crofters from their laird. He, however, realising that, no matter how unreasonable the laird’s action might appear, he was acting within his legal rights, informed Burroughs that the veto would be strictly adhered to, but at the same time asked if there was any quarry where Inkster would be permitted to take stone. Would he be permitted to buy building stone or could he open a quarry on his own land? Burroughs was quite open about his intention. The Crofters Act, he replied, obliged the crofters to keep up their houses but the proprietor was within his rights to prevent quarrying and that was exactly what he intended to do.

Andrew Thomson thereupon published the whole correspondence in the press and both local papers were forthright in their condemnation of Burroughs. No legal action was taken against Peter Yorston of Oldman who reluctantly accepted the veto, although protesting vigorously in a letter to The Orcadian. But because Inkster had told the grounds officer that he intended to continue to take stone and was reported to have claimed a right to quarry on his own croft, an action for interdict was brought against him and was granted by the Sheriff. At the same time a further interdict was sought against Betsy Craigie of Fa’doon. In September her son-in-law, William Grieve, was quarrying building material when he heard that other crofters were in trouble. He immediately abandoned the stones he had already cut but, two months later, thinking the fuss was over, he brought them home. In this case the Sheriff dismissed Burroughs’ application for an interdict on the grounds that, although quarrying was contrary to estate regulations, Betsy Craigie, like other former tenants-at-will, had never been given a copy of the regulations nor had she been warned that the traditional freedom to quarry was being withdrawn. Burroughs, in seeking these interdicts, had won the first case and lost the second, yet it would be wrong to think of the honours as having been equally divided. As Sheriff Armour said in granting the interdict against Inkster:-

It may be that a landlord who so chooses to act inflicts great hardship on his tenants, and, perhaps in certain cases, he may defeat the Crofters Act and get rid of a crofter by this indirect means. It appears to me, however, that as the law at present stands, he is within his rights.

The second case had merely established that, before a landlord could obtain an interdict, he had to make sure that the tenant knew the estate regulations or had received a proper warning. The Sheriff’s decision was confirmed by the Lord Advocate when Burroughs’ affairs were once again raised in Parliament by the member for Orkney and Shetland. The Lord Advocate considered that there was no need for fresh legislation since the abuse was not widespread and the landlord was not breaking the law.

With the onset of winter, the plight of seventy-six-year old Inkster was becoming increasingly desperate. He had moved out of his house in the summer thinking that repairs would soon be completed but he now had ten cartloads of stone at his door which he was interdicted from using. In November, while carrying a caizie of peats into his makeshift quarters in the barn, he accidentally stumbled against the doorway of the ancient building, causing the collapse of the whole precarious structure and damaging his household effects. He is reputed eventually to have repaired both buildings using a cargo of building stone purchased in Westray.

The dispute dragged on for years, with Burroughs remaining adamant in his refusal to allow crofting tenants access to quarries. The law having been unable to protect them and Parliament having refused to consider a change in the law, the crofters’ only redress now lay with the Commission. But even the Commission was precluded from immediate action since the fair rents already determined had by law to run for seven years before they could be reviewed. In 1897, when this period had elapsed, seven crofters applied for a reduction in rent on the grounds that the action of the proprietor put them to additional expense in building and repairing houses, steadings, dykes and drains.

The Sheffield Independent newspaper of October 16th 1890 reported on the proceedings within its columns:

LANDLORD TYRANNY IN ORKNEY.

THE ACTION OF THE CROFTERS’ COMMISSION.

General Burroughs, the holder of some crofting property, is creating some excitement in the Orkney Islands by the bad grace with which he receives the decisions of the Crofters’ Commission, which is concerned in adjusting for the Crofters the legal rights which Parliament has given them. According to some recent issues of The Orcadian, copies of which have been sent to us, the General seems to hold himself entitled to thwart the purposes of the Act, even to the exposure of his own foolishness. It appears that the dwelling house on the croft of Swartafiold having become unfit for habitation, the crofter, Mr. John Inkster, took it down and proceeded to erect, at his own charges, a new house with stones from “an old use-and-wont quarry on the commons.” This course was dictated by considerations that might be called personal, but also by regard for the law which imposes on crofters the duty of keeping their holdings in good condition. However, the eye of General Burroughs was upon him, and Mr. Inkster, along with another crofter, was treated to a solicitor’s letter, intimating that if the quarrying was not instantly stopped an action of interdict would be raised, and, over and above, the offenders would be reported to the Procurator-Fiscal for theft. An instructive correspondence followed. General Burroughs was informed of the circumstances under which the quarrying was being done; that the dwelling house had been taken down; that the crofter was house-less; and he was asked – (1) whether there was any quarry on the estate from which the crofter could obtain stones; (2) or, alternatively, whether he might open a quarry on his own croft; (3) whether he might be permitted to use the stones he had already quarried on payment of surface damage or a small lordship. To this the general replied that he could not prevent a crofter erecting any building on his holding, but he could prevent him quarrying stones; and that he was determined to do. This was absolute enough, but the crofter ventured one more appeal, “Was he at liberty to quarry stones from waste or other suitable ground on his own croft?” to which General Burroughs answered “neither on his own croft nor elsewhere.” So, if it be at all within the compass of General Burroughs’s power, the crofter is to remain houseless; he is to contravene the Act by allowing his holding to become dilapidated, or he is to take his fate in his hands and his stones from the quarry and hazard a sentence for theft. The Scottish Leader, under these circumstances, advises the crofter to build his house with the best stones he can get from his croft, and to let General Burroughs do his worst, adding, he could not go to gaol in a better cause. But the gaol is not so easily made ready. General Burroughs, in spite of his tasteless threat, will find it rather hard to prove that a crofter who takes stones from his own croft to build a respectable house on General Burroughs’ property is committing a felony. Whatever be the true motive, General Burroughs is lending a service to land law reform; and if he will only have the crofter clapped in gaol, Radicals will have the more to thank him for.

Writing in his own defence, General Burroughs says: – “My case is this. Some 1900 acres of my land in Rousay have been forcibly taken from me without compensation, and have been handed over to a class of persons who have no more right to it than has any reader of this newspaper. These people are called crofters, and my land has been handed over to them and to their heirs and successors for ever, so long as they choose to continue to pay for it a rent below its market value, and fixed by the Crofter Commission – a Commission consisting of three men, who, contrary to all law until recently in force in Britain, have been invested with the despotic power of a Czar of Russia, and the infallibility of the Pope of Rome, and against whose unjust decrees there is no appeal! And at the mercy of these three men have been placed the reputation and the estates of landowners in the so-called “Crofting counties” of Scotland. He complains that John Inkster and Peter Yorston, who, before the Commission, made out that they were too poor to pay their rent, as soon as they had succeeded in getting it reduced and obtaining fixity of tenure, their poverty was soon forgotten, and they set about pulling down the existing buildings and erecting new ones on his land without consulting him, and without his permission they took stone from his quarries to do this.

The following is extracted from an edition of the Shetland Times dated October 18th 1890:

AN ORKNEY LANDLORD AND HIS CROFTERS.

REMARKABLE CORRESPONDENCE.

The following correspondence has passed between Messrs Macrae & Robertson, solicitors, Kirkwall, and Mr John Inkster, Swartafiold, Sourin, Rousay, and Mr Andrew Thomson solicitor, Kirkwall. Messrs Macrae and Robertson, agents for the General, wrote as follows to John Inkster: – “We are informed that you are quarrying stones upon General Burroughs’ property without his permission. If we do not hear from you within five days from this date that you have ceased quarry, we shall raise an action of interdict against you in the Sheriff Court and report you to the Procurator-Fiscal for theft.” To this Mr Thomson replied: – “Your letter of 16th instant to Mr John Inkster, Swartafiold, Sourin, Rousay, has been handed me. The veto put by you upon his quarrying stones in the old use-and-wont quarry on the commons will be strictly observed. I understand you are aware that the former dwelling-house on the croft, having become ruinous, and threatening to fall, has been taken down and that Mr Inkster was in course of erecting, at his own expanse, a new dwelling-house upon the croft in substitution for the old one. In this way he went to the quarry, which he understood had all along been freely open to the whole tenantry. As he is at present houseless, I shall esteem it favour to be informed at your early convenience whether Mr Inkster can quarry stone in any quarry upon the estate, to enable him to re-erect his dwelling-house, and, if so, from what quarry, or alternatively whether he can open a quarry on his own croft. Mr Inkster has about as many stones quarried in the quarry referred to as will enable him to erect his house. Cannot he have these on paying surface damage, or on payment of a small lordship?” Messrs Macrae & Robertson, in answer to this, wrote: – “As we are aware, under the Crofters Holdings Act, General Burroughs is powerless to prevent a crofter erecting any building upon his holding. He can, however, prevent their quarrying stones on his property, and we are now instructed to inform you that if either the tenant of Oldman, or Inkster, the tenant of Swartafiold, quarries or removes or makes use of any stone from General Burroughs’ property, they will be at once interdicted.” Mr Thomson then asked: – “ Would you kindly inform me whether General Burroughs will allow the crofters to quarry stones from waste or other suitable ground on their own crofts?” and, in reply, received the following: – “General Burroughs will not allow quarrying on any part of his lands, either on their own crofts or elsewhere.” The last letter is from Mr Thomson, who says: – “I need not recapitulate the circumstances. These crofters are bound not to dilapidate their holdings. Their houses having become ruinous and dangerous had been taken down, and were in course of being rebuilt in terms of the Act. General Burroughs steps in with threats of both civil and criminal prosecution, both of which are unwise, the letter reprehensible. The result is that these crofters are meantime prevented absolutely not only from rebuilding their houses, but they and others are prevented from draining and improving their land.”

The People’s Journal commenting on the above, says: – People who take an interest in the affairs of the crofters are not unacquainted with General Burroughs. The General is one of the landlords whose high and mighty notions of his rights on the face the earth have greatly helped advance the cause of the Land Law Reform in the North. Of course he hates the Crofters’ Act and everything connected with it, and his latest performance among his tenants is evidently designed to show his contempt for the Act and his desire to get some of his tenants back into the grips from which it has rescued them. Under the statute, crofters are required to keep their houses in good repair. It they fail to observe this condition they may be removed. Now, some of General Burroughs’ tenants are the occupants of tumble-down houses. These they resolved to rebuild at their own expense and for this purpose they took stones from a quarry on the estate which has hitherto been open to the tenantry. The General by all sorts of threats stopped them from taking stones from this quarry, he refused to let them have the stones for payment, he forbade them to open a quarry on their own crofts, and, lastly, he has refused to let stones be taken from any part his lands. What is to be thought of a landlord who thus shows his childish impotence against an Act of Parliament, which the more he kicks against its provisions will be the more strengthened to restrain him from mischief?

Reference was made to

The Little General and the Rousay Crofters

by

William P. L. Thomson:

(John Donald Publishers Ltd. Edinburgh)

and the

British Newspaper Archive