Nicol Mainland was the son of James Mainland and Christian Louttit of Cotafea and he was born on June 9th 1800. In 1830 he married Margaret Louttit, daughter of William Louttit and Isabella Craigie of Faraclett. She was the twin of Janet and they were born on January 19th 1803. Between 1831 and 1846 Nicol and Margaret raised a family of seven children.

The following tale of an incident involving Nicol, which occurred here in Rousay many years ago, was written by Robert Craigie Marwick. My thanks to the editors of The Orkney View, Alastair and Anne Cormack, for allowing its reproduction.

…………………………

It was close and airless in the box bed and old Nicol could not get over to sleep. From time to time, Maggie nudged him and muttered sleepily about lying still. He knew it was not just the warmth of the night that was keeping him awake; he could not stop thinking about the events of the day that was now dying in the western sky.

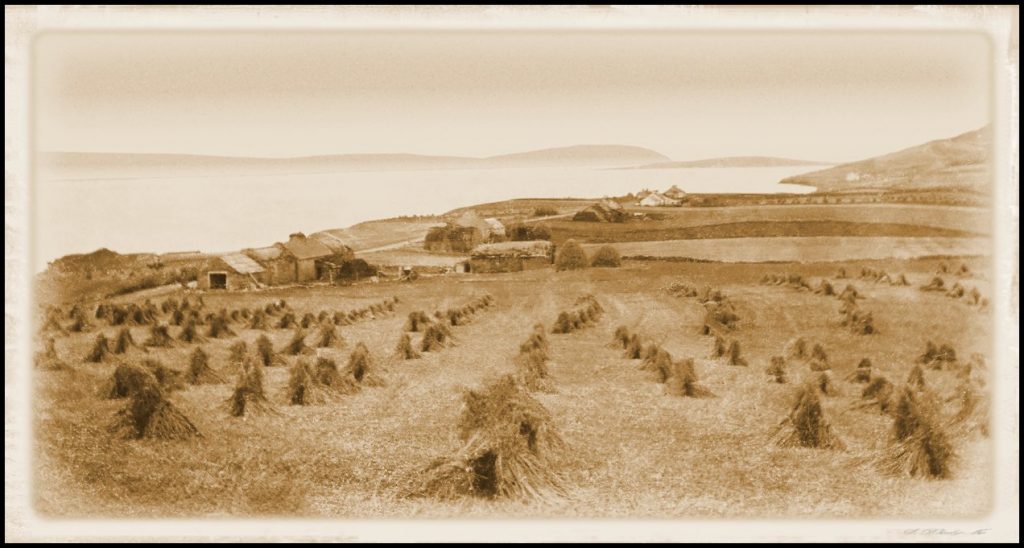

The day had started uneventfully enough. While his son had gone off to the hill for another load of peats, Nicol busied himself building up the stack with the last load brought home the previous day. It was a warm, sunny day, warm enough for him to shed his heavy jacket. The sun felt good on his old bones as he piled up the peats. In the afternoon he harnessed the old mare and yoked her to the scuffler. It was a good day for dealing with the weeds in the neep field down by the shore. The old mare’s slow and steady pace would suit him fine on such a warm day.

He had taken no more than two or three wups with the scuffler when he spotted the stranger coming along the shore. By the time Nicol turned towards the shore again, the man was standing on the end rig waiting for him.

“It’s a grand day,” said the stranger as Nicol reached him. Nicol turned the mare into the next drill before answering.

“Aye, hid’s ower weel,” he replied, at the same time pulling his pipe and a stump of black twist from his pocket.

“Here, have some of mine,” insisted the stranger, offering Nicol a full pouch. The old man declined politely and began searching for his knife with which to cut up his small bit of twist.

“I see you haven’t much left so try a fill of mine. It’s good stuff. I’m sure you’ll like it.” He again held out the pouch. Nicol took his first good look at the stranger. His shiny skipped cap, his clean-cut appearance, and clear, blue eyes showed him to be a man of the sea. Nicol liked the look of him.

“Hid’s guid o’ thee,” said the old man. “Mibbe I’ll hae a fill right enoff,” and took the pouch. When his pipe was filled and going well, Nicol nodded appreciatively to the stranger and turned again to his work. He would have liked to know who the stranger was but considered it would be an impertinence to ask straight out. The man would tell him in his own good time, he reckoned.

As Nicol prepared to set off up the drill, the stranger asked if he might walk with him for a little while. “Fine that,” replied the old man. Up and down, up and down the drills they trudged, with the stranger saying very little apart from an occasional remark on how well the crops were looking and a question on whether Nicol had anyone to help him with the work on the farm. After a couple of hours the stranger said he would need to be on his way and held out his hand. “I’m glad to have met you,” he said as he grasped Nicol’s hand firmly in both of his.

“Hid’s been lightsome right enoff,” Nicol was surprised to find himself saying, being well aware that very few words had passed between them as they walked up and down behind the scuffler. Still, he had enjoyed the younger man’s quiet company.

“Take care of yourself,” said the stranger. Then he smiled and turned towards the shore. The old man, with a puzzled expression, watched him go. Just a friendly smile, he told himself, and yet……A hundred yards away the stranger turned and waved. Nicol raised his hand, and then, turning to the task in hand, clicked his tongue and the old mare moved off.

That evening after tea, Nicol took his stick and set off on the short walk across the fields for his usual midweek visit to the shop at Hullion. His neighbour, Jeems o’ News, who ferried mails and passengers across Evie Sound each day, was already there chatting to the shop-keeper. The latter, when he saw old Nicol coming in, reached beneath the counter.

“I daresay this is whit thoo’re efter,” he said as he handed Nicol an ounce of black twist. Nicol paid for the tobacco and proceeded to fill his pipe.

“Thoo wid be plaised tae see thee viseetor the day, Nicol,” remarked Jeems. “I saa him gaan ap and doon the neep field wae thee a long while this efterneun.” Nicol made no reply until his pipe was going well.

“Hid wis ower weel, bit best kens wha hid wis.”

“Did thoo no ken wha hid wis?” asked Jeems in surprise, and when he saw the blank look on his old friend’s face he realised he would have to explain matters carefully.

“I took thee viseetor ower fae Evie and I kent wha hid wis when he asked me whar thoo lived. He’s the spittan image o’ his uncle, Jock Harrold, that I worked wae for a term in Egilsay afore he set aff for Australia.”

“Harrold, did thoo say? Wis that……wis that Isabel’s boy? Wis that wha hid wis?” asked Nicol, incredulously.

“Aye, Nicol, that’s wha hid wis. Isabel Harrold’s boy. Thee son, Jeemie.”

Jeemie, thought Nicol. The bairn Isabel Harrold had borne him. It must be fifty year, aye, maybe one or two more. Isabel Harrold. My, what a bonny lass she had been with that head of red hair and that smile of hers. The very same smile, he now realised, as he had seen that afternoon.

In response to Nicol’s urgent questioning, Jeems o’ News had told him about taking Jeemie back to Evie in the late afternoon and when last seen he had been making for Aikerness. It took a little persuasion for Jeems to agree to cross the Sound with Nicol that evening in the faint hope of catching up on Jeemie before he got too far. At Aikerness they were told he had set off for Kirkwall right away on the hired bike on which he had arrived, saying he planned to catch the six o’clock steamer for Leith. Wearily they trudged back to the shore and, without a word being spoken, set sail for home.

Now, in the silence of the night, Nicol’s thoughts took him back fifty years to that time when he had fee’d at Faraclett and had first met Isabel Harrold. She had lived with her mother on the little croft of Peeno up by the Suso Burn. Fondly, he recalled the joys of that summer and the sweet sorrow of parting when he left in the spring for a season at the whaling in the Davis Straits. It was only when he returned that he heard about the bairn born during his absence, and the death of Isabel’s mother shortly afterwards. He had listened, with ever increasing anger, to an account of Isabel being summoned to appear before the kirk session to be given a tongue lashing by the minister. An elder who had been present had later told Nicol it was the most vicious he had ever heard. Isabel had not been there to tell him anything of these events for she and the bairn had left the island after her searing kirk session ordeal, and before his return. Gone to Leith, some claimed, where she was said to have relatives. She had never returned to the island, but must have told the boy about his parentage and he had returned. Nicol smiled contentedly in the dark.

After another session at the whaling, Nicol had fee’d again at Faraclett, and a year later had married Maggie, a daughter of the house. She had been a good wife to him all these years, and he had no regrets, he told himself.

As the dawn of a new day dispelled the long darkness of the night, Nicol drifted over into a blissful sleep and into a dream in which a younger self frolicked with a smiling, red-headed lass on the summer banks of the Suso burn.