William Alexander Mainland was born in Frotoft, Rousay, in 1763, or thereabouts. He, his two brothers, David and Alexander, and their parents lived at Tratland.

On April 10th 1795 William is on record as being an Ordinary Seaman aboard the 32-gun frigate HMS Astraea. An ordinary seaman was a man assigned to deck jobs as a trainee on ships. Working and gaining experience as a trainee followed by a couple of years as ordinary seaman allowed an individual to get a promotion as an able seaman.

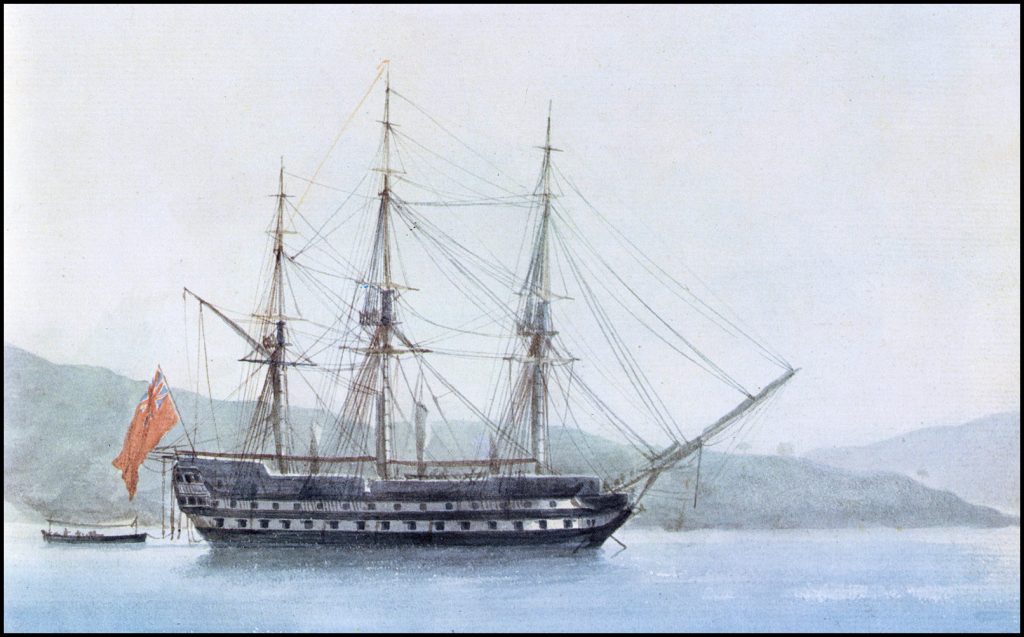

The Astraea was a 32-gun frigate of 689.27 tons burden with an overall length of 140 feet, the length of the lower deck being 126 feet, a beam of slightly more than 35 feet, and a draft of 17 feet forward and 17½ feet aft. She was built in Robert Fabian’s boatyard at East Cowes, Isle of Wight, and launched in 1781. Having been rigged and fitted out she was commissioned in Portsmouth on October 1st, 1781, and with a total of 220 men and officers making up her roster, she was finally ready for duty in the Royal Navy.

Seamen were assigned various duties and rates dependent on their capabilities rising from Landsman when unskilled through Ordinary Seaman to Able Seaman when they could ‘Hand Reef & Steer’. The youngest and nimblest would be assigned to sail handling and were called topmen. Experienced hands might be given a minor responsibility such as Captain of the Maintop overseeing sail handling in that position or coxswain of a ship’s boat. A seaman joined a particular ship not the Royal Navy and in theory his service ended when the ship paid off although in time of war he was likely to be pressed immediately if he did not volunteer for further service in a new ship.

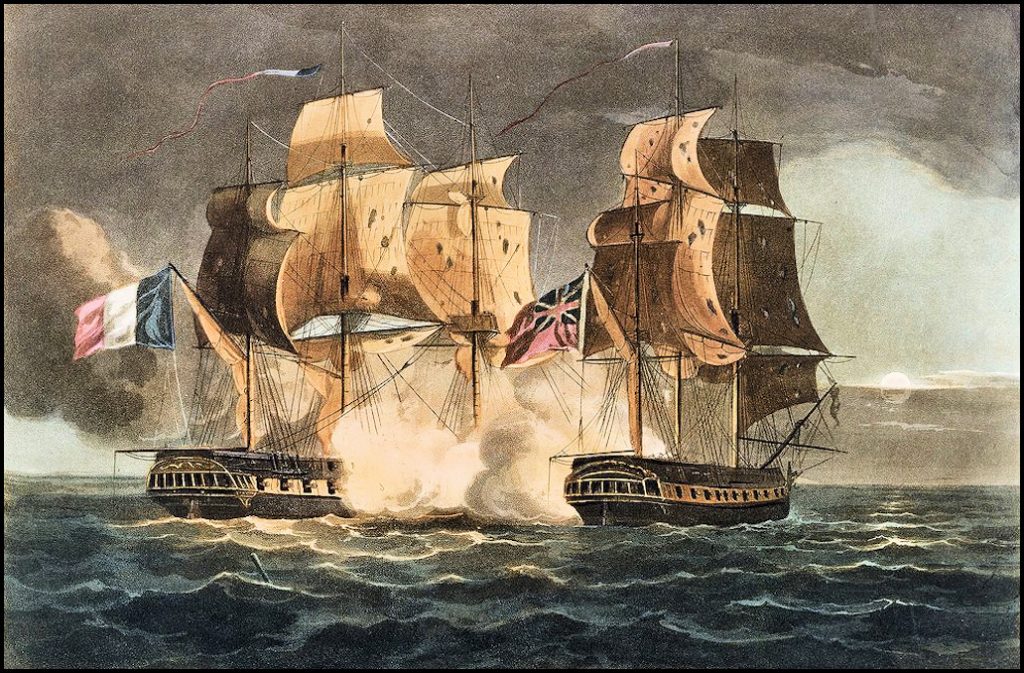

With the treaties of Paris and Versailles in 1783 an end was put to the war and for a period of ten years Britain was at relative peace. With the French invasion of the Netherlands early in 1793, however, Britain was once again drawn into war; and so was Astraea. Although she had played only a relatively minor role in the capture of the South Carolina ten years earlier, she was to score her first real triumph on April 11th 1795 when she captured the larger 42-gun French frigate La Gloire off the French coast near Brest, Brittany. At the time Astraea was commanded by Captain Lord Henry Paulet and she carried a crew of 212 men, whereas La Gloire carried a crew of 280 men. The first gun was fired at sunset and only after a long and severe battle did the French frigate strike her colours just before midnight.

Two months later on the 22nd of June, while Astraea was cruising with a fleet of 25 vessels commanded by Admiral Bridport on board the first-rate vessel Royal George, a French fleet consisting of 23 vessels was sighted. Due to light and variable winds the meeting was delayed 24 hours, by which time the fleets were off Groix, an island off the coast of Brittany in north-western France. According to British sources the actual engagement lasted four to five hours and resulted in the capture of three French vessels carrying nearly 700 killed and wounded men, while the British claimed a loss of less than 150 men.

According to William’s service record his next ship was HMS Victory. On May 11th 1803 his rank/rating was Able Seaman, and his ship’s pay book/service number was SB519. Under the comments section the word ‘prest’ was used, meaning an advance of money had been paid to him when he enlisted in the Royal Navy.

The ship’s Captain and nine commissioned officers were in overall charge of the ship and the crew, whilst warrant officers like the Boatswain, Gunner, Carpenter, Surgeon and Purser were specialists responsible for a single aspect. The Master, for example, looked after navigation and the ship’s log. The Royal Marines provided the ship’s fighting force and numbered 11 officers and 135 privates.

The great majority of the crew – over 500 – were the seamen who sailed or fought on the ship. These men were rated (and paid) according to their skill and experience; from the 70 skilled petty officers, through the 212 experienced able seamen and the 193 useful ordinary seamen right down to the 87 landsmen – who were without previous experience of the sea.

Able seamen like William Mainland were very experienced sailors who could serve at any of the stations of the crew. They could tie dozens of different knots, and knew when and where to use each. They could find any rope or line in the dark, make emergency repairs and instruct the younger men. When the men worked in isolated parts of the ship such as in the masts and rigging, the senior able seaman took command of the others, supervising their work.

For these men, living and working at sea was dangerous; it is estimated that 90% of the 92,000 British fatalities during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars with France were caused by disease, accident and shipwreck. However, many of the aspects of life at sea which appear to us harsh, such as child labour and corporal punishment, were also a part of life ashore. Navy service was attractive in many ways. Although basic pay was relatively low (23s. 6d. a month for an ordinary seaman in 1805) compared to that of merchant seamen, the crew were guaranteed regular food and drink and a chance of prize money. William’s prize money amounted to £1 17s 6d. He had a Government grant of £4 12s 6d, and his monthly pay was £1 13s 6d. Experienced sailors would have been aware that, with many more men aboard, their duties were actually lighter than on merchant ships. The old belief that Victory’s sailors were forced to serve by the Press Gang, or were convicted criminals who chose to serve in the Navy rather than sit in gaol, is too simplistic. Among the crew at Trafalgar were 289 volunteers, as against 217 who had been pressed into service and no one at all who had been recruited from prison.

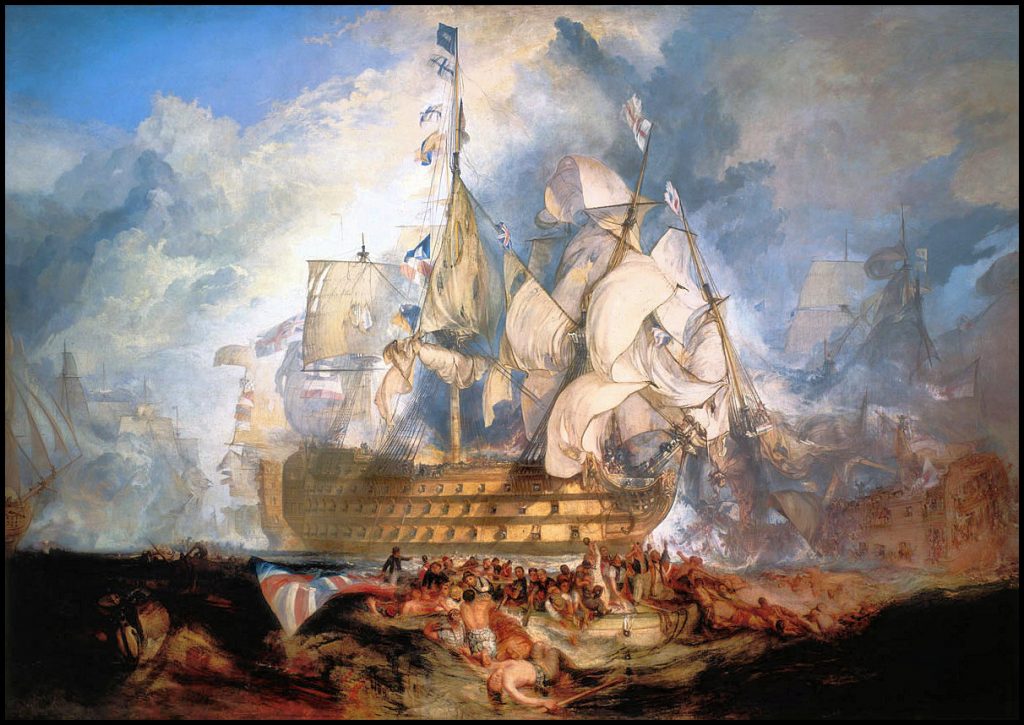

a painting by Joseph Mallord William Turner

In five hours of fighting, the British devastated the enemy fleet, destroying 19 enemy ships. No British ships were lost, but 1,500 British seamen were killed or wounded in the heavy fighting. The battle raged at its fiercest around the Victory, and a French sniper shot Nelson in the shoulder and chest. The admiral was taken below and died about 30 minutes before the end of the battle. Nelson’s last words, after being informed that victory was imminent, were “Now I am satisfied. Thank God I have done my duty.”

Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar ensured that Napoleon would never invade Britain. Nelson, hailed as the saviour of his nation, was given a magnificent funeral in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Back to William’s service record. After Trafalgar he spent a brief time on board HMS Ocean, and then joined the crew of HMS Fame, a three-masted 74-gun ship of the line, on January 17th 1806. His ship’s pay book number was SB66 and his rank/rating was Able Seaman – but on January 31st he was promoted to the rank of Quartergunner.

There was one quartergunner for every four guns on board a ship. The main duties of a quartergunner consisted of assisting the gunner, keeping the guns and carriages in working order and ensuring that there were sufficient supplies for their use. One of his tasks was to keep two matches burning day and night suspended over a bucket of water, for the gun’s themselves would have been kept in a constant state of readiness. The quarter gunners wore no special uniform or distinguishing marks but they were allowed small privileges such as sleeping on the berth-deck or on the cable tiers. They were paid between £1.16s and £2.2s per month.

HMS Fame’s armament was as follows: On the Lower Gun Deck were 28 British 32-Pounders; Upper Gun Deck 28 British 18-Pounders; Quarterdeck 12 British 32-Pound Carronades; Quarterdeck 2 British 18-Pounders; Forecastle 12 British 32-Pound Carronades; Forecastle 2 British 18-Pounders; and in the Roundhouse were 6 British 18-Pound Carronades.

In the Mediterranean in November 1808, whilst under the command of Captain Richard Henry Alexander Bennet, HMS Fame joined a squadron lying off the Gulf of Rosas. Captain Thomas, Lord Cochrane, was assisting the Spanish in the defence of Castell de la Trinitat in the province of Girona against the invading French army. Boats from Fame helped evacuate Cochrane’s garrison forces after the fort’s surrender on 5 December.

In June 1813 HMS Fame, under the command of Captain Walter Bathurst, participated in the siege of the Spanish port of Tarragona and rescue operations of sunken transports at the mouth of the Ebro. Fame returned to Chatham, and William was discharged from the Royal Navy on October 3rd 1814 ‘per Admiralty order.’

After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 the government awarded a medal to every man who had taken part. The naval veterans of Trafalgar had been presented with an unofficial medal paid for by the industrialist Mathew Boulton whilst the crew of HMS Victory had received a similar unofficial medal from Alexander Davidson, Nelson’s Prize Agent. To make matters worse for those who valued their medals, soldiers were allowed to wear their Waterloo medals but sailors and marines were not allowed to wear their unofficial Trafalgar medals.

In 1848 the government relented and announced the award of the Naval General Service Medal. All naval veterans were to receive a medal with the clasp for each action they had taken part in. However the veteran had to be living to make their claim. Of the 18,425 sailors and marines at the Battle of Trafalgar only 1,561 survived to claim their official medal.

William Mainland indeed fought at the Battle of Trafalgar and survived! He was awarded the Navy Medal with Trafalgar bar in 1848. He lived latterly in the north-east of England, near Newcastle. For many years, William’s medal was in New Zealand where most probably it was taken by one of the children of William’s nephew, boat builder John of Cruseday – two sons, Hugh and John, and daughter Jane Hughina, who went to New Zealand to act as housekeeper for her elder brothers who had emigrated some years earlier. In more recent times the medal was returned to George William Mainland [son of John and Betsy Mainland, Cott, born in September 1897] who had the tattered ribbon replaced. It was later in the possession of John Mainland of Nears/Cruseday [son of Robert and Edda Mainland, born 1930], the great, great grand-nephew of the man to whom it was awarded – and the medal is now in the safe-keeping of John’s son Robert. My grateful thanks go to him for allowing me to photograph it.