The fourth and final part of ‘Sourin,’

written by Tommy Gibson, Brinola, Rousay

Food

Most farms and houses had a planty creu. This was a small walled garden usually away from the house or steading. I can mind a few creu’s still being worked in Sourin in the fifties, this was usually planted with early tatties and keel (cabbage). The ground in the creu was always in good heart. When Willie Inkster of Woo moved to Faroe, he tided up the old creu and which was dug and manured. He tended the plants all summer, and in the rich soil they bloomed.

Potatoes were the staple diet, and when the tatties were nearly, and it was a waste digging up whole plants, it was not uncommon to see folk purran in the drills for a dinner. I will explain, purran for tatties was scraping around the roots of the plant for enough of the largest of the immature potatoes for a dinner.

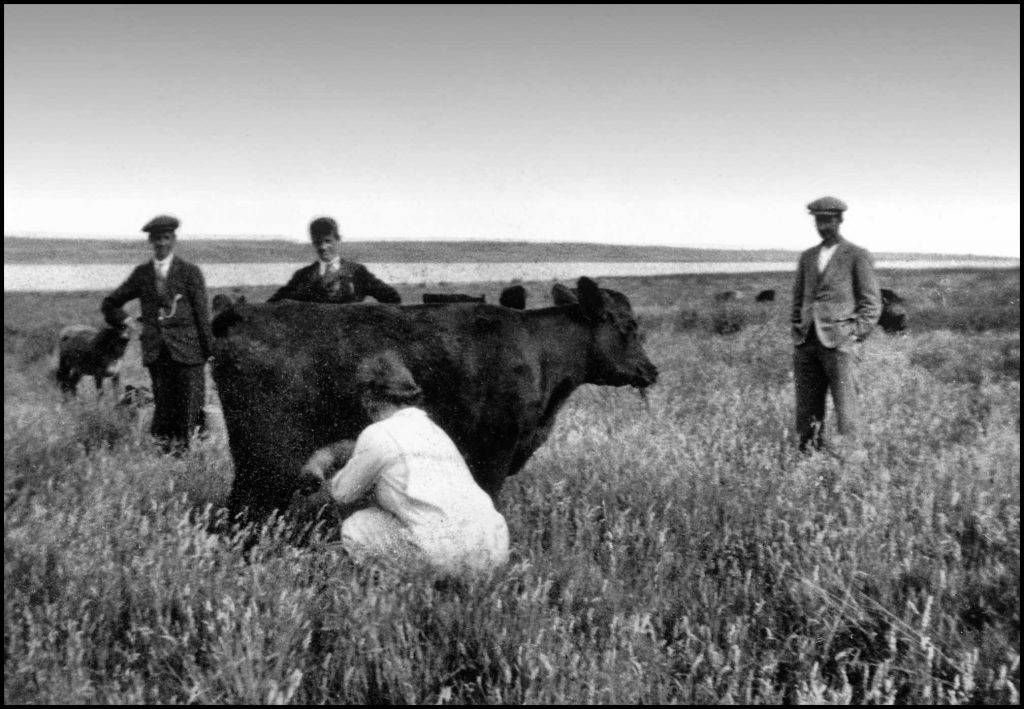

Looking on is husband Harry Sinclair [right] and their sons Harry jr, and Gordon.

When tatties were boiling you had to try the tatties, this was to see if they were boiled and when the tatties were ready they were syed (drained). And long ago they were put on the table without a dish, this was common practice in most of the farmhouses. When kye was milked and the calves were given their ration the remaining milk was taken into the house and syed through a syer. The syer (it must have had magical properties) was a large sieve with a very fine gauge wire filter. This was to take the odd piece of straw, cow hair and even the odder impurity out of the milk. Then it was safe to use. Nobody ever used the milk before it was put through the syer. Water used to be carried from the wells and springs. Up to the 1950’s very few houses had piped water into the houses; water was carried from springs or wells. All good wells had their clocks in them, and it was said that water from a well without clocks was not good. Clocks were water beetles.

Most of the houses had pigs! Pigs were a valuable food. Some were housed inside, some roamed around outside. Killing pigs was only done by certain folk in the district. In those days, no-one had a piece of paper to say “I have a licence to slaughter”. I remember in Sourin, the late James Russell, Myres, Hugh Gibson, Bigland, Hugh Mainland, Hurtiso, and James Lyon, Ervadale, all killed pigs. This was always done at the respective houses. Of all the jobs and traditions I think was the worst, but speaking to these men they did not agree. All of them had a pride in what they did, and carried out the job in a very professional manner. The day of the killing, a large amount of water had to be boiled for the plat (to remove hair). The pig or pigs were led out for the kill. The carcass was then amerced in the “platting tub” and cleaned, then a block and tackle hoisted the pig to the twartbacks in the barn, then it was gutted. Very little if the pig was lost, and folk lived on various dishes of fresh pork for a week or so. The rest was salted down. Pigs were usually to 220 to 250 lbs and some houses fed the pig to a massive 300 lbs. This was a big carcass.

Baking was usually done every day. Bere, flour and oat bannock adorned the tea table. No bannock today can compare with the bread baked with kirn milk (butter milk). All baked on the yetleen, (girdle), (spelt as said).

Boreholes and springs

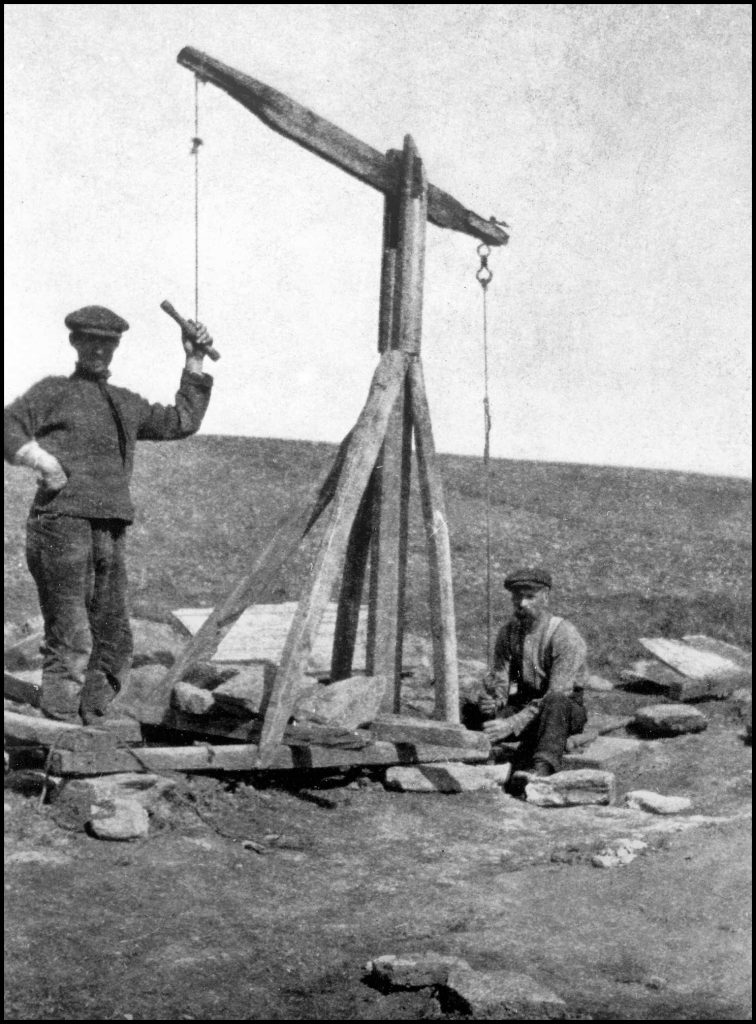

The very first borehole in Sourin was at Bigland. This is situated on the East side of the meadow. 1954 was a dry summer and Hugh Gibson decided to have water troughs in the fields and have a proper bathroom in the house. This needed a good supply. Water was divined and a large hole was dug out by hand down to bedrock. A homemade T-shaped drilling rig was then erected over the hole. This was driven by an Iron horse, this was a British Anzani tractor, with an arrangement fixed to the driving wheel to lift a jumper. The jumper then bored a 3-inch hole in the rock. As the hole went deeper the jumper got heavier, but the rock also got harder, someone had to sit in the hole slowly turning the jumper. Some days the jumper went down, perhaps 3 feet, and other days they were lucky if they managed 1 foot down. Water was found at 55 feet. The surface of the ground at the site was 30 feet above sea level and the bore went down 95 feet. I can remember discussions about seawater in the supply, but this never happened. It was an excellent supply with the water rising to 15 to 20 feet below the surface. A small shed was built and an engine and pump installed. This bore is still in use today, and as good as ever.

John Harrold, Springfield, and William Sutherland,

blacksmith, Viera View, drilling for water at

Brinian House in the late 1920s.

The only bathrooms in Sourin in the early fifties were in the two manses and the district nurse had one in Woo. A new house was built at Banks, started in 1949-50 and this had a bathroom. It was in the sixties that bathrooms came became common in houses. The bathroom in Bigland was the fifth in Sourin.

Every household had to carry drinking water from a well or spring. The water was usually poured into a large earthenware jar. A tin with a handle soldered on the side was called a jeck or tinnie. This was dimmled into the water for a drink.

There are lots of water springs in Sourin, but there are half a dozen seriously strong springs never been known to go dry. The first one is the Meean Well, situated below Essaquoy in a field called Fananoo. In very dry summers I can remember, cattle from Bigland, Swandale, Broland, Hurtiso, Fa’doon, Breck and Myres were driven at different times to this well for a drink. I can remember the folk of Faraclett carting water in a wheeled tank behind the tractor. This was for their own use and also drinking water for the cattle, sometimes this happened twice a day. This water was cold and pristine clean, and the supply more than adequately coped, it flowed out at a steady rate. It was nigh on impossible to keep this well empty of water by a bucket. I remember sticklebacks were common in the burn in the early fifties, but I have never seen them since. One wag said that he threw a filly (part of a cart wheel) into Gin Janet, a small loch near the top of Kierfea, three days later it came up in the Meean well!! The next is Oro, a well on the land of Knarston. The next spring is on the lower land of Ervadale and as far as I know, no name. The last but not least is a spring on the lower land of Brendale, which is fed to Woo, again a very strong spring which never dries up. There is also a very strong spring supplying Faroe.

House Names

Many house names in Sourin were pronounced differently to the spelling. Firstly Faraclett was always known as Fara-klee. Wasdale was Wassdeal. Swandale was Swen-dal, Stand Crown, Styno, Stand Pretty was Pretty, Midgarth was Midier, Gorehouse is G sounds as D. Goard, a enclosed field, hence Goarhouse (Dyorehus). The best one is House Finzie, a small croft on Banks was known as Finyo. Near Brittany was Hillside, now gone, as was Bogle Ha, Windbreck was known as WindyWa’. Above Curquoy were two houses, East and West Crey. This spelling is wrong; the nearest to the pronunciation is Krei.

and peat banks showing up after a dusting of snow on Brown Hill.

Wrestling

A lay. In cold weather men working outside at menial tasks would get cold. One way to get warm was to have a lay or a wrestling match, but this was not to decide a winner, it was only to get the blood circulating again. Two well-known Sourin men, one from Woo and the other from Brendale, were fencing across the road from Essaquoy, the day was cold. One said to the other “bouy, weell hae a lay” The two men started up, grunted away for a while, and one of them got up and walked away. He had a broken arm. “Bouy” he said, “thoo ar stronger than thoo lucks”.

A couple of Stories

It is strange how stories stick in the mind. The story below was told to me by someone in Sourin in the early sixties. I remember the story well but I cannot remember who told me. Below Knapper there is a quarry. Long, long ago as the story says, lived two old ladies in a small house near to this quarry. This two lived in abject poverty. Through time one of them died, and the parish buried her. Time passed and the other one died, again she was buried by the parish. When neighbours went into the house to sort out what meagre effects there were, the only sustenance left in the house were some salted snails. This must have happened a long time ago, as there is no record in any census of a house in that locality. There is no indication of a house or steethe there.

This one is on a lighter vein. The old man in Sourin had a very sore back. He lay groaning in bed for a few days. His wife fed up with this went to the shop at Banks and bought some Winter Green. Back home, she lifted his shirt and starting rubbing his back. She became a little too generous with the Winter Green, and with the heat of his body the rubbing melted and slowly ran down his hips. After a few moments a terrific pain forced him out of bed, next thing, his wife saw him in the water barrel, outside the door cooling off. The Winter Green went too far down!

Place Names

Dr Hugh Marwick’s excellent book “Rousay place names” gives most of the place names in Rousay but not all. Unfortunately over the years a lot of unrecorded names have been lost. Some of the old men like Alan Gibson of Bigland, Old John Craigie of Breck, Jeemie Willie Grieve of White Ha’, all were a fountain of knowledge of the district, but all gone. Some names in Sourin not in the place names are Girss-e-quoy, (Grass quoy) a field above Swandale.

The Grit o the Nort Green, this is an area to the north of Broland where were two dried up ditches. I have no idea how or what this means. The Long Sheet was the name of the field of Woo above the crossroads. Between Heshiber and Scroo on the Head of Faraclett was a fishing place called the “New Found Craig”. It is not an easy place to find and access to this place was a near vertical face of rocks. This was the most dangerous fishing rock in Rousay.

Jeemie Willie Grieve, White’ha, with his wife

Mary Ann and visitor Jean Hackston. c.1930

Digro

In the mid 1960’s Digro was sold. It was bought by The Hon Ivor Montague and his wife, Hell (Helen). Their other home was in Watford. His family were merchant bankers, and he was a director of the London Zoo. When he was at Digro he was always writing and travelling around in his mini-van. On fine days he went down to Saviskaill for a swim; he would walk out with his plimsolls on to chest height then swim back to the shore.

Thrashing Mills

In Sourin, due to the hills, ditches and burns run towards the sea, and farmers were able to use this water to thrash their grain. Farms who had a water driven mill in Sourin were, Curquoy, Digro, Fa’doon, Broland, Banks, Pretty and Gorehouse. Farms who had a mill course were, Wasdale, Ervadale, Brendale, Essaquoy, Bigland, Hurtiso, Breck, Myres, Pow, Faraclett, Scockness, Woo, Knarston, Glebe and Avelshay.

James Leonard’s skills as a mason, as is a miniature water-mill

standing behind the original house and supplied from

a small dam farther up the hillside.

Technology came to Rousay in the late 1920’s. John Logie of Myres bought a two hp. Lister engine for driving the thrashing mill. Engineers came out from Kirkwall and installed the machinery. They left instructions how to start the engine and a can with two gallons of petrol. No petrol pumps then. Everything went well for about two months. One day the engine would not start. They tried for about an hour, and failed. Those engines had to be started with a “wap” (handle). John went to Breck to his neighbour for help. “Bouy, dis thoo ken anyting aboot the leem and iron thing on the side o the engine”. A new name for a sparking plug.

Old Johnny Gibson of Broland bought a Tiny Mill; this was a semi high-speed mill, and was made in Banff, Scotland. It was driven by a two-horse power Lister engine, which made the thrashing drum rotate at 750 rpm. The drum usually has five rows of beaters with about twenty inch-and-a-half iron spikes. A very efficient tool. Shakers or straw walkers separated the grain from the straw. When mill and engines were new, all the old farmers had not the slightest idea how to work the mill. This was a dangerous piece of machinery. Old John was feeding the mill with a sheaf, and this sheaf pulled his hand into the drum and he lost most of his hand. Help was sought from the doctor who in turn put for an ambulance from Kirkwall. A steamer was sent out with the ambulance, which in turn collected John and back to the hospital. This was the first time an ambulance was in Rousay. Isabella Grieve, a servant girl and a first cousin of John saw this accident happening; this gave her a tremendous fright, which she never recovered fully. The time of this accident was about 1930-1. Isabella died on October 23rd 1932 aged 32 and John died on December 9th 1934 aged 90.

Whales

I have read that whales came ashore in Sourin. This was in the Bay of Ham at Scockness in 1861; the whales came into the Sound and the Sourin men drove them ashore. Sixty animals were in the pod, some were over sixty feet long. This number of whales must have filled the small bay to capacity. Some of them were rendered down for oil and £260 pounds were paid for this. This would have been quite a windfall to the Sourin men. The stories of this event are very limited, which happened over 140 years ago. One old man who was killing the whales with a large gully (knife) was stabbing away, somehow managed to cut his hand in two. There was so much fat and meat left over that farmers from Scockness, Faraclett, Pow and Myres carted the blubber on to the land as a fertiliser. There is still part of a backbone from one of these whales still in a dyke at Woo in Sourin. It was another jawbone and vertebrae at Rose Cottage, in the Brinian. The jawbone was used as an arch for a gate, this is long gone, but the vertebrae is still there. Over the years a few dead whales have drifted ashore in Rousay, nothing remarkable about this, but one huge whale came ashore in a small bay, to the north of Faraclett, called the “North Sand”. Legend has it, that the whale was so large that it nearly filled the bay. Nothing more about this is known.

Tommy Inkster, Woo; Michael Grieve, Knapper; Lilly Miller.

Socialising

Long before radio and television, people went visiting each other’s houses; this was an important part of socialising. There were many reasons for this event, people would gather at a house for perhaps, singing, checkers, gossip, or perhaps just for seeing friends or relatives. The evening would pass and usually supper was given. When the folk went home, it was not unusual for them to be followed home, talking all the way. This was a common custom, possibly more so in the summertime.

Many stories were told about the folk going to the houses. In the days before torches or Tilly lamps there were not many visible lights on a dark windy November evening to guide anyone anywhere. I have heard about a man who left Brendale to go to Treblo, he ended up at the Glebe – about a mile off course. Another man left Hanover and ended up in Frotoft; he was going to Wasdale. Misty evenings was another problem. When folk left a house after a visit in the summertime thick mist sometimes came down like a blanket. Folk would leave a house and after a while they lost all recognition of the land, and soon had no idea where they were.

All black and white photos were provided by the author