Saviskaill is an ancient farm between the Loch of Wasbister and the beach at Saviskaill Bay. Mentioned in the Early Rental of 1503 as Savirscale, the name comes from the Old Norse sœvar-skáli, ‘sea-skaill,’ i.e. hall or house by the sea. The presence of two skáli names in this part of Rousay – Saviskaill, the skáli or hall by the sea, and Langskaill, the long skáli – is significant, pointing, it may be suggested, to early Norse settlers of chieftain or semi-chieftain class.

The very situation of the former – not in the heart of the old Wasbister tunship, but on its outskirts on the seashore – would seem to imply that the head of the settlement was not unmindful of his responsibilities, and wished to be as near as possible to his longship in case of need.

An old Rousay legend survives about a witch called Katho. This lady is said to have been churning in the house of Saviskaill one day. She churned away harder and harder until at length the milk foamed up over the lid. She then stopped and exclaimed: “Tara gott, that’s done; Saviskeal’s boat casten awa on the Riff o’ Saequoy.” And sure enough at that time the boat was wrecked.

It would seem that ‘Katho’ – the notorious Orkney witch Katherine Craigie – was a healer in the Rousay community. According to the Register of the Privy Council of Scotland during the Orkney Witchcraft Trials in 1643, almost half of the accusations made against her by her neighbours were to do with healing someone and curing them. With this in mind it would appear that Katho was a relatively ‘good witch’. Her case was similar to many other witch trials in that she was accused of cursing animals and people which resulted in their deaths. Although she was accused of having the devil as her master, there were no suggestions in the proceedings that she ever met him. – Katherine Craigie was sentenced to death on 12th July 1643 “for airt and pairt of the using and practeising of the witchcraftis, sorceries, divinatiounes and superstitiounes…”. She was then taken by the lockman “hir handis behind hir back, and caryit to the place of execution and thair wirreit at a staik and burnt in ashes”.

A ship was wrecked close to Saviskaill in 1783. Subsequent occurrences on the island must have aroused suspicions in official quarters because a man with seafaring experience was sent from Stromness to Rousay to make enquiries and to report. He found the stranded vessel to be one of 33 tons, which had been carrying a cargo of brandy, gin, and tea. All the cargo had been removed from the vessel before his arrival but he saw about 50 casks, which were still on the scene. Some were offered to him for sale but he declined to buy. In the house of Alexander Marwick of Saviskaill the investigator saw two books lying on a window ledge. Both books were soaking wet from seawater and he suspected they had come from the stricken ship. Not so, replied Marwick. Both books were his and had got wet when they fell into a tub of water. Marwick did admit having some casks of spirits and the captain’s chest in which he found six ruffled shirts, a half guinea in gold, a pair of silver buckles and a silver watch. Taking possession of these items from the ship must have troubled him less than having the water-soaked books.

Nigh on a hundred people were busy breaking up the ship, and among them were Alexander Marwick, his son William and his cousin David. The investigator warned them that they would be called to account for their actions but he was told that the wreck was God’s send and that coming between them and such divine providence was no business of his. He considered it prudent, ‘being a stranger in the place,’ to say no more. Several people told the investigator that Alexander Marwick was the first to discover the wreck and that one member of the crew, although found floating in the water, had still been breathing. ‘For the sake of the wreck,’ it was alleged Marwick gave the man no assistance and allowed him to die.

Another inhabitant of Saviskaill was John Inkster. Originally from nearby Innister, he was married to Barbara Marwick and they had seven children, born at Saviskaill between 1794 and 1810; Margaret was born in 1794/5, James in 1796, William on January 24th 1799, Robert on December 7th 1801, Janet, on July 19th 1803, Hugh on October 20th 1807, and another Janet, who was born on November 13th 1810.

The rocky shore of Saviskaill Bay claimed another victim in late October, 1811. The German registered barque Juliana Catharina, Capt. Wallis, carrying flax and hemp, came to grief with the loss of eight of her crew.

James Inkster born in 1796 was the tenant of Saviskaill according to the census of 1841. He married Barbara Mainland, daughter of David Mainland and Margaret Sinclair of Tratland, who was born on December 27th 1799, and they had four children. The three eldest were born when they lived at Lerquoy in Wasbister; John was born on November 8th 1821, James on February 4th 1827, and Margaret on April 3rd 1831. David was born on September 21st 1823 after they moved to Saviskaill.

By 1851, a 23-year-old farmer named Samuel Seatter from Evie was head of the household at Saviskaill. 56-year-old John Flett was farm overseer, and they employed four farm servants – David Inkster, William McKinlay, John Craigie and Margaret Craigie. Margaret Baikie was the housekeeper, and Janet Craigie was a servant in the house.

In 1861, 34-year-old William Seatter was farming the 236 acres at Saviskaill. His wife Jane was 28 years old and they had a one-year-old son, Frederick. They employed four domestic servants; Margaret Baikie (77), Margaret Flett (26), Margaret Cerston (18) and Janet Kirkness (12). John Flett, was a 67-year-old farm servant, and there were also three ploughmen; Hugh Inkster, Malcolm Leonard, and John Yorston, all in their early 20’s.

By 1891 William had died and the land at Saviskaill was farmed by his widow Jane and her 18-year-old daughter Emily. They employed three servants; Jessie Taylor (27), Alexina Sinclair (19), and Samuel Marwick (18). They also had two boarders staying with them who existed upon private means, Robert G. Gordon, and William Wotherspoon.

At the turn of the century Saviskaill was occupied by 26-year-old Walter Muir, who was born at Lady, Sanday. With him was his sister Isabella and four farm servants: Jane Muir, a 30-year-old dairymaid; Robert (25), and Thomas Muir (22), who were horsemen; and John Grieve, who was a seventeen-year-old cattleman.

The 1911 census was carried out on April 5th, and it tells us that Walter was married and had a family, and that they had moved from Saviskaill to nearby Breckan. He and his wife Bella had been married for eight years and by that time had raised five young children. Walter’s sister Isabella lived with them, and was employed as a domestic servant.

Meanwhile, Saviskaill was occupied by the Moar family. William Moar was a sixty-year-old farmer from Birsay, and his wife was 55-year-old Jane from Rendall. With them were their children: David, a 27-year-old ploughman (foreman), Mary, a 20-year-old lass who assisted on the farm (dairy), and her 16-year-old sister Maggie who also assisted on the farm in a domestic capacity. Another sister, Lizzie (12), was at school, and with them was William Velzian, who was a 24-year-old servant and employed as a ploughman carter and general worker.

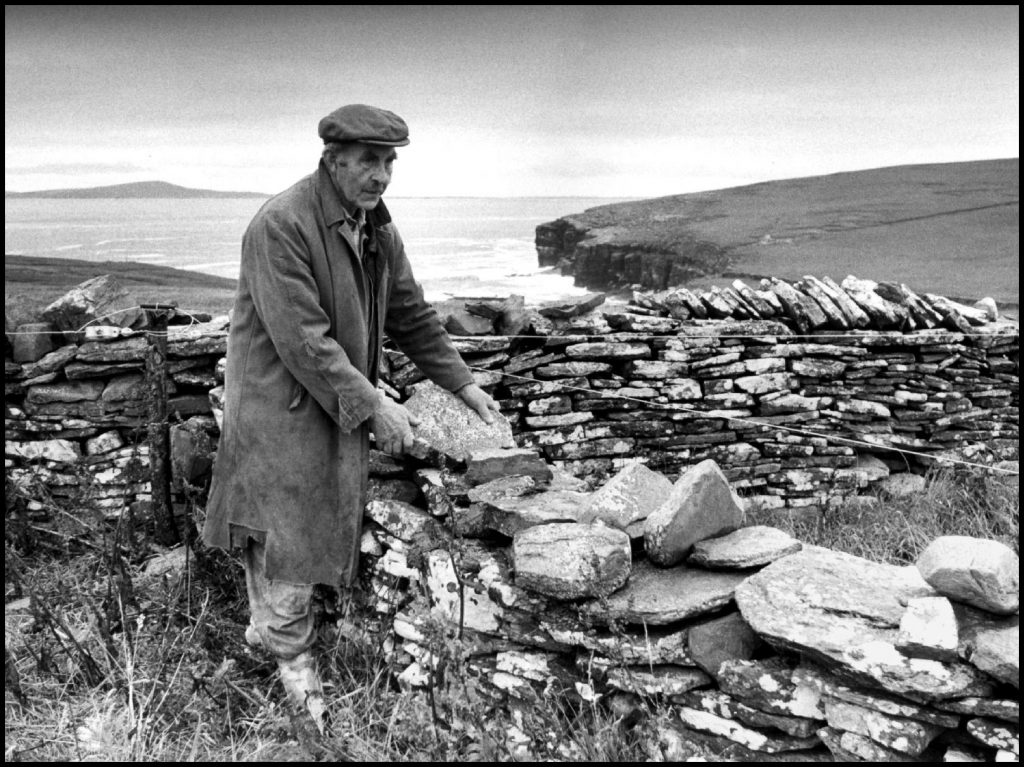

A much later occupant of Saviskall was Hugh Grieve. I came across him as he was repairing a stone dyke near Grithen in 1975. Hugh was originally from Fa’doon, but moved to Saviskaill after marrying Janet Mainland of Hurtiso.

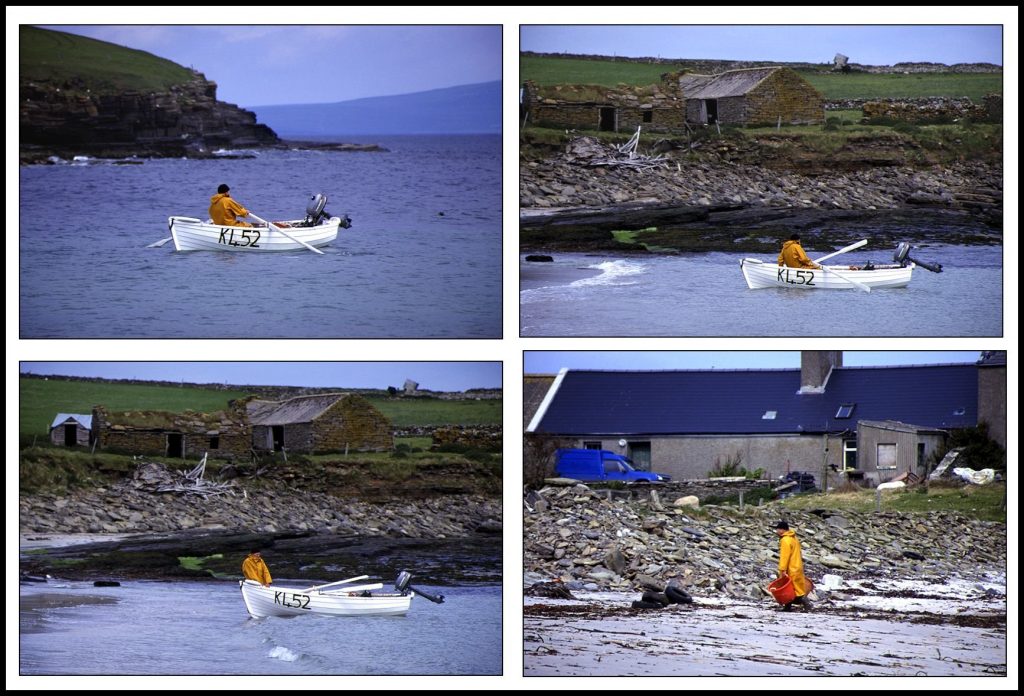

The last of my photos shows Hugh’s son Colin in 1999, beaching his boat at Saviskaill after another successful day at the fishing.

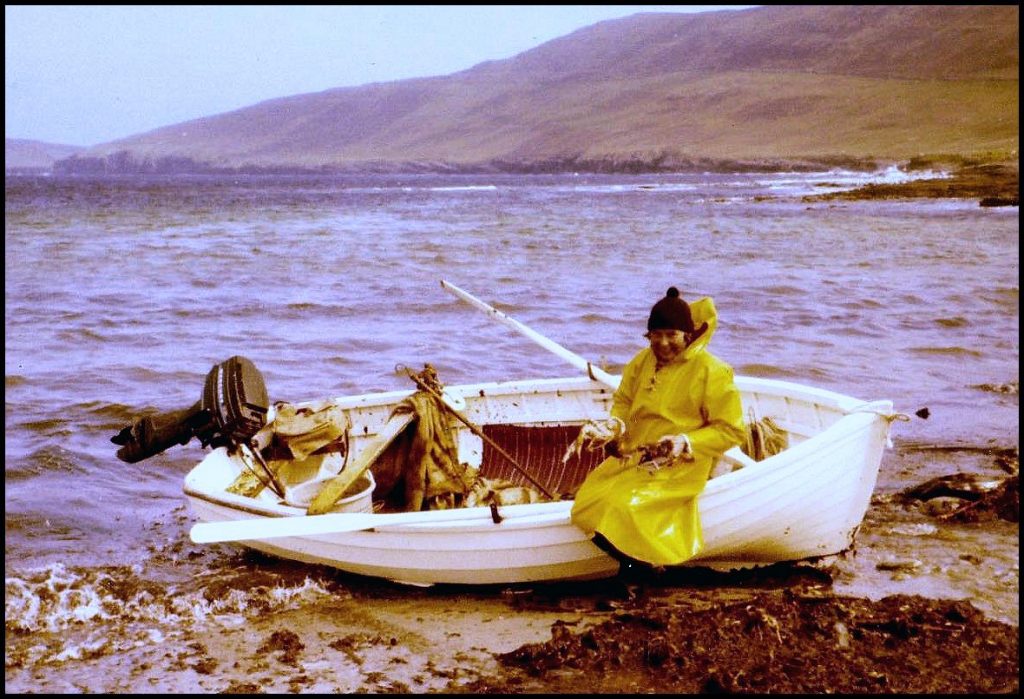

The photo below is courtesy of Athol Grieve, and shows his uncle Colin doing what he liked best – fishing for lobsters in Saviskaill Bay…..

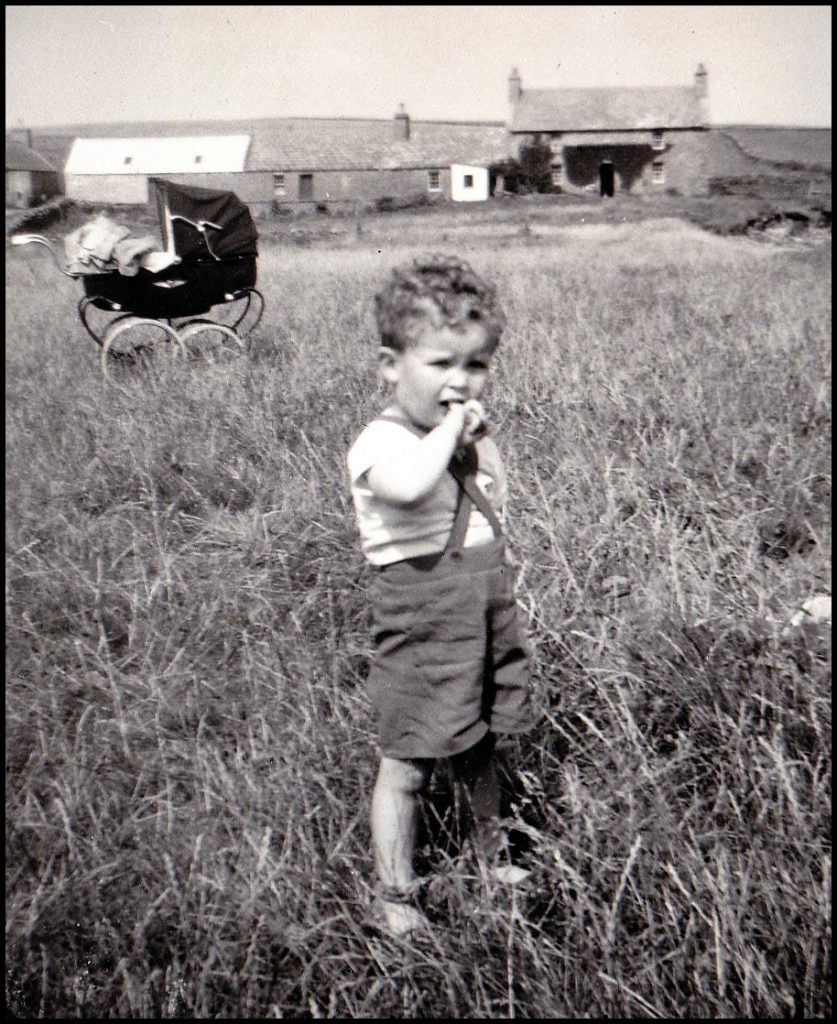

…..and below is a photo of a very young Athol, pictured at Saviskaill with his ‘first set o’ wheels’!

Finally, below is a fine family photograph taken at Saviskail, kindly supplied by James Grieve. His caption runs as follows:

‘This photo was taken at Saviskaill circa 1996. From left to right: Myself (cough, cough…), Linda Grieve (granny), Kirsty Grieve (sister). Back: Ellen Grieve (mum), Hugh Grieve (great grandad – photographed above building the dyke near Grithin), Athol Grieve (dad), and Colin Grieve (great uncle – photographed above landing creels)’.