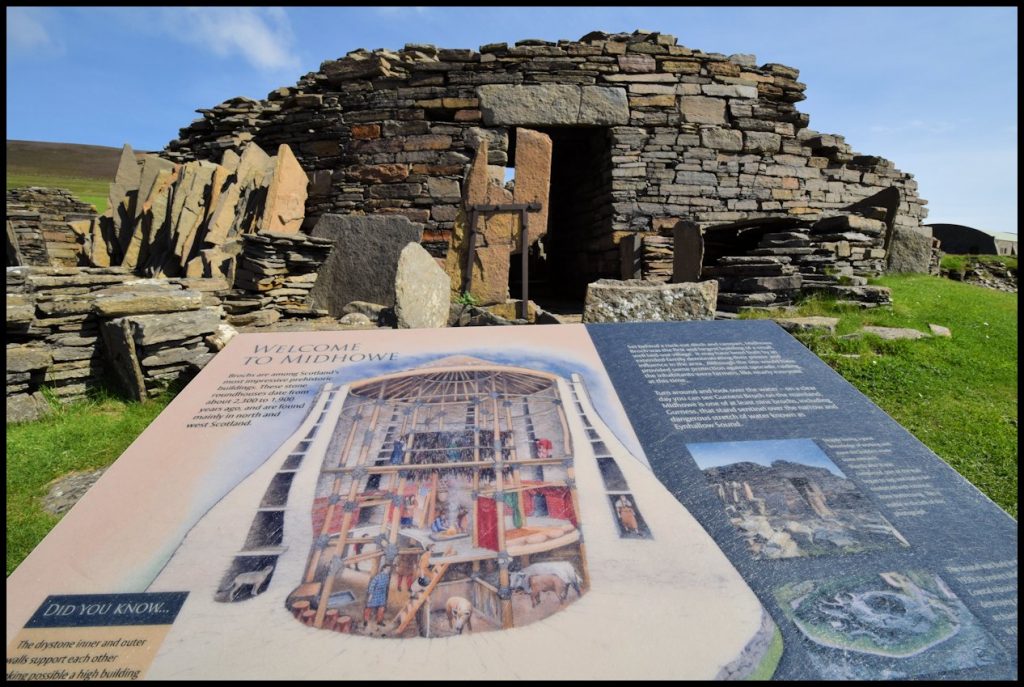

Rousay abounds in prehistoric sites of archaeological interest, with over 100 recorded so far. It is likely that some have been lost forever by farming operations while others lie beneath the soil still hidden from sight. Less than a third of those on record have been examined through either complete or partial excavation. The variety of structures found include brochs, burial cairns, standing stones, Norse burial cists, earth-houses, burnt mounds or knowes, and Celtic chapels. The two best known and most visited of Rousay’s ancient monuments stand close to of each other on the Westside shoreline. They are the Midhowe Broch and the Midhowe Stalled Cairn.

Constructed and used sometime between 200BC and 200AD, on first glance the broch at Midhowe would appear to have been built with defence in mind. Standing on a promontory formed by two geos, the broch is protected on one side by the sea and on the landward side by a stone rampart and ditch. This massive rampart is built in an arc between the two geos and effectively cuts the site off from the land.

Although there is no doubt that these outward defences would have looked impressive in their heyday, it may be that they were merely built for dramatic effect – the southern end of the rampart stops short of the geo and therefore leaves a ledge on the rock face by which a “visitor” could have easily access the promontory.

Like the Broch of Gurness on the Mainland coast almost opposite, Midhowe was surrounded by a group of external buildings but these were probably from a much later date when the need for defence was not as important. Coastal erosion, a problem for all shore sites such as Midhowe, has greatly damaged the remains of these outhouses

The remains of the broch’s circular wall stand to a height of approximately four metres and within the structure the general layout of the ground floor has been remarkably well-preserved.

Large slabs of local flagstone were used to divide the interior (diameter 9.6 metres) into two smaller, semi-circular rooms that were then further divided into smaller cells each with its own hearth and water-tank. Water was supplied from a spring that flowed up through a crack in the rocks and during the excavations, it was written that the main storage tank retained water which: “remained clear and drinkable all the years the work of excavation was going on.”

Midhowe’s broch structure is interesting in that it had a ground floor gallery built into the walls and as such differs from the normal solid walled brochs found in the islands.

This hollow base was probably not a good idea because at some point during its occupation, the broch’s gallery had to be blocked and filled in when the walls threatened to collapse. A projecting ledge, about three metres (11 feet) up would have at one time supported a timber first floor.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Midhowe is the artefacts found within during excavation. The majority of these were the normal domestic items as you would expect to find on such a site – tools, whetstones, quern-stones etc. However, the Midhowe Broch yielded a few surprises as well. Among the items uncovered were the remains of a bronze ladle and some shards of pottery. These items had a definite Roman origin and as Orkney was well away from the areas of Roman control, they must either have been acquired as gifts or through trading or raiding excursions south.

The discovery of bronze jewellery on site also hints at the wealth and status of the family unit that lived at Midhowe. Archaeological evidence indicates that at some time a bronze-worker was based at the site but the small quantity of debris uncovered may simply mean that this craftsman was a travelling artisan.

The broch, a fortified and protected structure, was built as a place that could be retreated to in times of danger. It was excavated in the early 1930s and it was at that time also that the protective seawall was constructed in front of it.

Built by local stonemason Stanley Gibson, with assistance from Peemo Smith and Willie Grieve, this semi-circular seawall is a remarkable structure of five-inch thick slabs of rock set on edge on the rocky foreshore like giant books on a shelf. It slopes inwards for most of its height and outwards for the topmost two feet. Both the broch itself and this seawall rampart, built to protect it from the ferocity of the heavy seas that strike this side of the island, bear witness to the skill and craftsmanship of Orkney stonemasons working on the same site 2,500 years apart.

A stone’s throw from the broch is the stalled cairn, a burial place dating back about 5,000 years to the time of the Stone Age people. When it was excavated in the early 1930s it was found to be a building over 100 feet long and over 40 feet in width. The walls are a massive 18 feet thick leaving the interior as a long narrow chamber only a little over seven feet wide and varying in height from four to seven feet.

Down each side of a narrow central passage the chamber is divided into 12 compartments by flag-stones set on edge, giving an appearance very similar to that of a cow byre. It was in these compartments or stalls that the remains of 25 bodies were found, all on one side of the passageway. The bones of some animals and birds were also found.

This stalled cairn was considered so important a find that a stone building with overhead lighting and an overhead viewing gangway was erected over it to protect it from further decline.