“Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society : 1923, Vol. 2:

pages 7-14: Old Orkney Houses 3 by J. Storer Clouston”

…..I have left to the last one structure which I believe myself to be probably the oldest two-storey house in Orkney, since the question of its age can only be judged after one has examined examples of the various known periods. This house is Tofts, one of the roofless crumbling buildings in the deserted district of Quendale in Rousay, abandoned in the year 1846 to the plover and the rabbits. The spray of the Atlantic salted its fields and the houses were out of date and in need of repair, and it was not thought worth rebuilding them. So that this whole collection of derelict dwellings, untouched since their inhabitants left them nearly eighty years ago, is extremely interesting.

The old mansion, with five small farms on the slope above, formed what was really a separate township from Quendale proper. In the “Uthel Book” of 1601 it is entered as “Toftis ob terrae uthall (i.e., a halfpenny land odal). The samyne apperteins to the Craigies and Yorstons, occupyed be Johne a Toftis.” In 1668 a sasine* of certain lands in Rousay, from William Douglas of Egilsay to his son, included his “halfpenny land in Wesbuster called Tofts, with the privilege of the uppa thereof, as the samen has in use been in all times bygane past memorie of man”[Tankerness Charters]; a statement which implies that the “uppa” or right to the first rig in every field in the adjacent township of Wasbister went with the house of Tofts, and proves the early importance of its owners.

*[a notarial record of a land transfer]

But though thus claimed by the Douglases, the Craigies actually remained the true owners, for in 1662 Magnus Craigie of Skaill wadset* his 1½ farthings in Tofts to Thomas Craigie of Saviskaill –and in 1664 the five daughters of the deceased James Craigie of Hunclett were infeft** in the other ½ farthing, which had belonged to their father. Later, in 1705, Jean Traill, daughter of James Traill of Westove and widow of Magnus Craigie of Skaill, lived there; so that it was presumably her dower house.

*[Scotch law. A right, by which lands, or other heritable subjects, are impignorated [mortgaged] by the proprietor to his creditor in security of his debt]

**[when a vassal (Feuar) obtains full title to land, he is said to be infeft]

These are the only documentary glimpses of the early history of Tofts, and we may now return to the house itself. Save that it has lost its roof, it still stands in tolerably good preservation, and externally there is, as at Tankerness, little to suggest great antiquity. It is a very small building, with a door in the middle, a window at each side, and, immediately above these, two upper windows, exactly like any elderly farm house of to-day, except for the size of the windows; which are only 1ft 6ins square below and a little smaller above. The east gable (the only one intact) is crowstepped, but that of course is a feature common to practically all the better houses down to comparatively modern times.

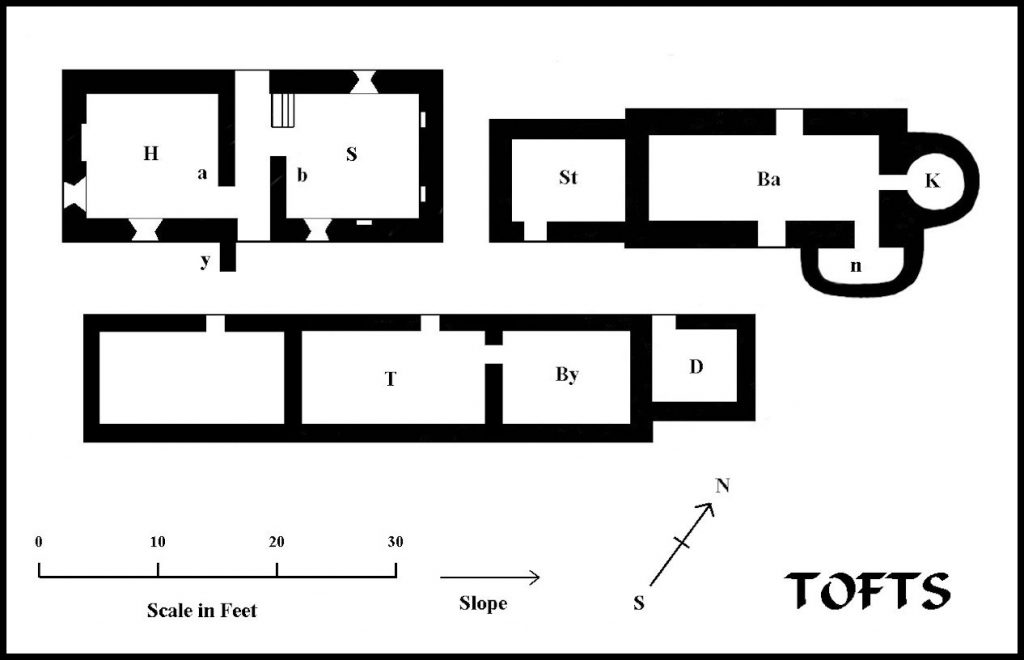

It is only when one examines the house in detail that the evidences of antiquity begin to appear. It is quite small; 32ft long by 12ft wide inside, divided with two rooms on the ground floor, of which H, in the illustration, is 12ft 6ins long and S is a trifle longer. The side walls are 2ft 8ins thick and the gable 3ft, all without lime, but exceptionally well built. Across the middle ran two cross walls, ‘a’ and ‘b’. ‘a’ still stands. It is only 1ft 6ins thick and ran up to the roof – ‘b’ has fallen. It was apparently of the same thickness, but only one storey high.

There was thus a stone passage a little over 3ft wide running through the house, and at each end of this was an outer door. The stone stairs are placed inside the room S, and rise along the north wall. Only a few steps are now left, but evidently one crossed the passage by a stone lintel.

Windows and doors are all grooved for frames and door posts, and the windows are splayed slightly outward beyond the groove. In each of the windows is a very neatly executed stone window seat.

Each ground floor room has two windows. H has a fire-place, but no recesses; S has three small square recesses but no fire. There is barely 6ft head room below the joist holes in these rooms.

Upstairs there were also two rooms, with side walls 3ft 9ins high, one small window in each, but no fire-places.

Outside the front door ‘y’ is a projecting wall to give shelter from the west winds.

Evidence of Age: – Taking the evidence afforded by these features, the cross wall ‘a’ in itself is proof of very considerable age, since no two-storey house with a cross wall is (so far as I know) to be found in Orkney later than the early part of the 17th century. The stone window seats and remarkable finish of all the stone work in the house show that it was originally a place of some pretensions, unquestionably a “gentleman’s house.” But what kind of gentleman indulged in stone window seats, and yet was content with rooms 12ft square and barely 6ft high, and with only one single fire-place in the whole building? These are the standards of a keep, and a keep of the earliest and simplest type, and give us a very significant indication that our gentleman lived in rude and far-off times.

And why did he have a stone tunnel through his house, provided with an exit at each end, and then stow away his staircase inside one of his rooms? Why also did the stairs rise awkwardly along the wall, where a bumped head at the top rewarded the careless, instead of across the house?

Again one is reminded not only of the standards but the uses of a keep. Suppose you wanted to raid this gentleman, with the view of either terminating his career or plundering his house, then you would begin to see some point in his arrangements. To begin with you must bring enough men to guard both doors, or he will slip out by one while you batter the other. Also, each party must be strong enough to resist a sortie, for you cannot tell which door he will sally forth from. Then suppose you have broken in; you find yourself enclosed in a stone passage with no room to swing a weapon, the inner doors still barred, the stair out of reach, and very possibly an aperture at the top of the stair for raking the passage with a blunderbuss. When one adds that the splayed windows are admirably contrived for firing out of and too small to jump in through, it becomes evident that if the houses were not actually built for defence, then it is a very curious coincidence that it should have been so well adapted for it. In fact the coincidence is so singular that personally I find it hard to doubt that it was originally designed as a semi-defensive structure.

In seeking for analogies for this type of house, one is met with the difficulty that the subject of early Scottish houses, other than castles, has never been dealt with save in the most fragmentary way. McGibbon and Ross, for instance, confine themselves to castles almost entirely. I have, however, been able to discover two buildings which seem to throw some light on Tofts.

One of these is an ancient house existing in Musselburgh at the end of the 18th century, of which a plan and some particulars are given in the Old Statistical Account [published in 1795]. It was only one storey high, but the ground plan was very like Tofts, consisting of two vaulted rooms with a vaulted stone passage between them running right through the house. In this house tradition stated that Randolph Earl of Murray, died in 1332.

The other is a 15th century house at Inverkeithing described, with plans, in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquities of Scotland for 1912-13. Here there was one room on each floor, with a stone passage running through the house alongside the ground floor room, leading to an outside stair at the back, which rose along the wall. The author says of this house:- “The high interest of this building lies in its showing that the first stone builders (of domestic structures), for lack of other tradition, followed closely after that of the small ‘keep,’ both in arrangement of parts and in details of workmanship.”

It seems clear that Tofts belongs to the same general type as these two ancient buildings, and in the second of them I think one can see the reason for the awkward position of the stair along the wall. It was simply an outside stair placed inside for safety, and the builder was so accustomed to outside stairs that it never occurred to him to turn it the opposite way and get more head room at the top. This at least seems to me the likeliest explanation.

We have thus, as very strong evidence of high antiquity, first the remarkable contrast between the finished workmanship and the single fire-place, and secondly the analogy of these two early buildings. But there are two further arguments that support this conclusion. At what period was a defensive house most likely to be built in Rousay? From early in the 15th century down to 1461 we know that the Orkneys were constantly raided by the Lewismen*, and traditions of these raids are actually still extant in Rousay. After 1461 there is no further record of them; and it may be taken that they had certainly ceased by 1471 when the Scottish Crown took Orkney into its own keeping; and therefore it is before these last dates that one would naturally look for a defensive structure in the island.

* Records of the Earldom of Orkney and also Highland Papers, vol. I.

Again, it is the only old two-storey house of which there is any tradition in Rousay and it was clearly a good house in its day, so that the very absence of anybody “of Tofts” or even “in Tofts” in the numerous Rousay records extant from about 1570 down to 1700*, shows that through that period it was not inhabited by anybody of local importance and strongly suggests that its glories had already departed before the first of these dates.

* The earlier records are contained in the Brugh estate papers, and in the 17th century, in the Saviskaill papers.

The illustration also shows the old farm buildings at Tofts:- The barn ‘Ba’, with kiln ‘K’, and neuk ‘n’; the stable ‘St’ attached, two byres ‘By’ and ‘T’, and a small building ‘D’. Another byre on the west end of ‘T’ is shown, though it is evidently later; but all the buildings in the plan are of the most ancient type. The narrow, thick-walled barn, in particular, is perhaps the oldest looking structure of the kind I have seen.

It is strongly to be hoped that this unique homestead will not be allowed to fall into further ruin, if any means, or any money, can be found to avert such a fate…..