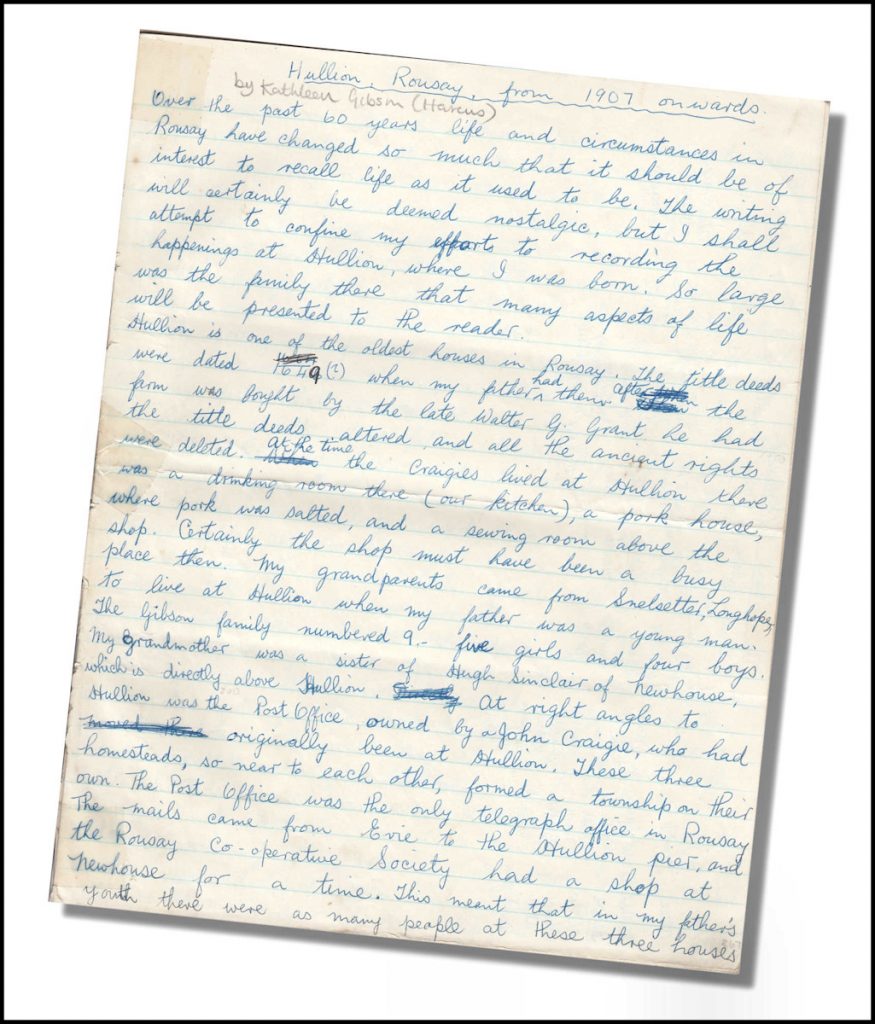

Hullion – From 1907 Onwards

by Kathleen [Kitto] Gibson

Kitto Gibson was a daughter of Hullion merchant James Gibson and his wife Mary Cooper. She was born in 1907, and as a child lived at Hullion with her six siblings. She was later a teacher at the Frotoft school, married Robert Harcus, and passed away in 1974 at the age of 67.

My thanks to Edith Gibson for allowing me to transcribe her aunt’s valuable handwritten document, and giving new readers a fascinating insight into Hullion’s past.

Over the past sixty years, life and circumstances in Rousay have changed so much that it should be of interest to recall life as it used to be. The writing will certainly be deemed nostalgic, but I shall attempt to confine my efforts to recording the happenings at Hullion, where I was born. So large was the family there that many aspects of life will be presented to the reader.

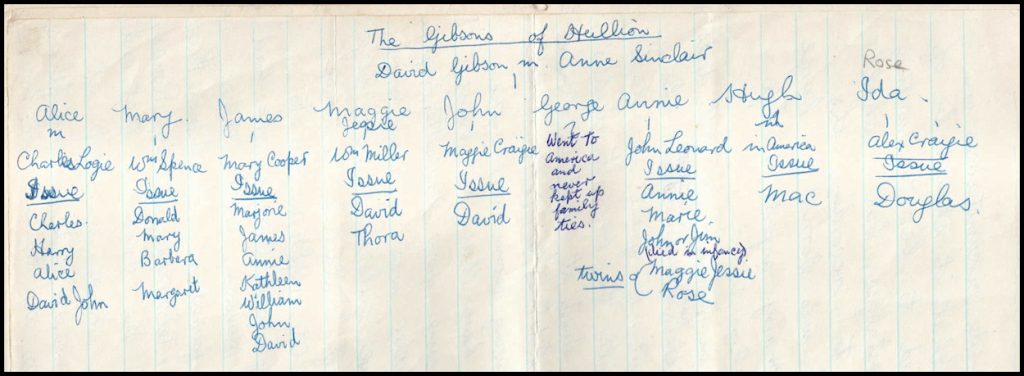

Hullion is one of the oldest houses in Rousay. The title deeds were dated 1649 when my father had them. After the farm was bought by the late Walter G. Grant he had the title deeds altered, and all the ancient rights were deleted. At the time the Craigie’s lived at Hullion there was a drinking room there [our kitchen], a pork house, where pork was salted, and a sewing room above the shop. Certainly the shop must have been a busy place then. My grandparents came from Snelsetter, Longhope, to live at Hullion when my father was a young man. The Gibson family numbered nine – five girls and four boys. My grandmother was a sister of Hugh Sinclair of Newhouse, which is directly above Hullion. At right-angles to Hullion was the Post Office, owned by John Craigie, who had originally been at Hullion. These three homesteads, so near to each other, formed a township on their own. The Post Office was the only telegraph office in Rousay. The mails came from Evie to the Hullion pier, and the Rousay Co-operative Society had a shop at Newhouse for a time. This meant that in my father’s youth there were as many people at these three houses as are now in all the houses from Westness to Hullion.

My grandparents made many alterations to the house when they took over Hullion. I imagine that it was quite a grand house then, but to us it was just our home! The kitchen was a low, cosy room, with a flag floor [long slabs of stone]. Hefty undressed beams held up the ceiling, which was really the floors of the two bedrooms above. I can remember an architect from the Office of Works suddenly getting up from his chair in the kitchen one day. He begun to measure the space between the beams and told my father that according to all the rules of architecture the house should have fallen down. My father’s reply was that “the auld hoose wid be standin’ when they were both in their graves”. This has proved true, altho’ the old kitchen, now no longer used, has at last got a sagging roof. The walls were three to four feet thick and there were two windows which opened like doors. The one at the front of the house was normal size, with four large panes of glass. The one at the back was tiny and also had four panes of glass. Apparently there was no window at the back when the Gibsons came there. My grandmother selected the spot for her back window. When the masons made a hole in the wall there they found a little window, complete with glass, which had been built up. The present window is still the same size. Its hinges are of leather and it is secured by a wooden “tirlo.”

A winding stair went from the outside door to the two bedrooms above. The first three steps were of stone and the others wooden. To cover up these steps in the kitchen a little closet was made. It was triangular and had a shelf about half way up the wall. The shelf was wide at the front and tapered into a point at the back. On the shelf were a basin and soap dish, while a long roller towel was fixed on the inside of the closet door. Here everyone washed their hands. At the back of the shelf there were boot brushes, stove brushes, flue brushes etc. Under the shelf stood the paraffin flask and the pail for dirty water. All clean water had to be carried in from the well, and all dirty water was carried out and emptied in the “middin”.

The kitchen furniture was plain – a table with drop sides and wooden chairs and armchairs which had to be scrubbed every Saturday. Other seating was a long wooden settle, an Orkney chair and a big creepie. A big press stood in one corner and a dresser and small girnel completed the furniture. The walls were always covered in gaily patterned paper and there were bright curtains at the windows. We had a downstairs sitting room and one upstairs. The one downstairs was in constant use, but “the best room” upstairs was seldom used. As children we called it the “chapel”, because of its unusual ceiling. The wooden ceiling was quartered, with lines running into a centre piece – rather like those in a church. There were quite a few good pieces of furniture in this room and many unusual ornaments. Pictures hung in tiers of three. There were thirty-six altogether. Father was quite dismayed when his young daughters reduced the number to twelve. He asked what we had done with “mother’s pictures”.

When I first remember there were eight bedrooms in use. Although the family was so numerous there was always room for guests. My mother kept boarders who had the use of the “best room” and the best bedroom and sometimes another smaller bedroom. The front door opened on to another stair – eleven wooden steps – which went straight up to the “best room” and four bedrooms. When paying guests were in the house we children didn’t use the front door and only used the stairs to get to and from our beds. In my schooldays there were five Gibsons, and four Leonards to get out to school every morning. The four Leonards were cousins – their mother was a sister of my father and a widow. It was quite easy, apparently, to keep nine children away from the front of the house. Instead of going up “the close”, which was what we called the nicely laid brigsteens, we used “the lower way” from the kitchen door. That way led down five rough stone steps to dairy, wash-house, byres etc. Then there was a cassied-walk for the cattle and a rough path along the midden dyke to the road. Although we children tried to be neither seen nor heard our boarders often found where we played with kittens and pups, or at some of our old fashioned games. They were anxious to speak with us and I’m afraid got some puzzling answers. One minister asked a cousin her name. She replied “ ‘Peggy’ – Maggie Jessie Leonard”. When asked what her brother’s name was she said “Billy Gibson”. Strangely enough we never used “thee” and “thou” when speaking. On looking back I think this may have been because even then we were talking very proper English in school and had teachers, doctors and ministers as family relations. The funniest sentence I recall is a question asked by a school inspector. He said to my mother, “Mrs Gibson, do you “thee” and “thou” your husband?” He must have noticed they did just this, although we children seldom used the words.

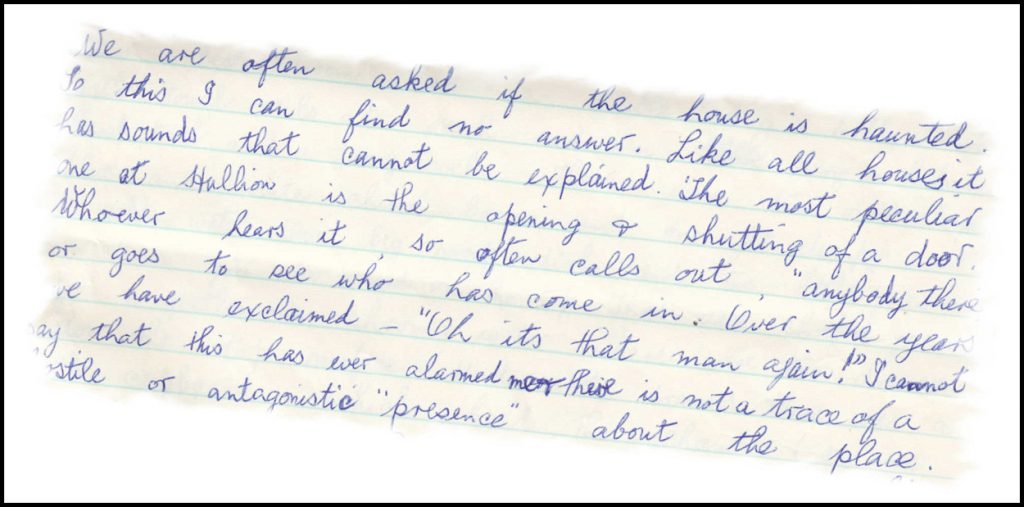

Our boarders came from various walks of life. We had our regulars – pension-officers, school inspectors and travellers. Dr Mackintosh, from Evie, often had to spend a night at Hullion. He attended patients in Rousay when there was no resident doctor. Other names that come to mind are the Storer Clouston family, and old Colonel Johnstone. He seemed a very quiet and retiring man, and thus we missed a golden opportunity for improving our botanical knowledge. We are often asked if the house is haunted. To this I can find no answer. Like all houses it has sounds that cannot be explained. The most peculiar one at Hullion is the opening and shutting of a door. Whoever hears it so often calls out, “Anybody there?”, or goes to see who has come in. Over the years we have exclaimed – “Oh, its that man again!” I cannot say that this has ever alarmed me and there is not a trace of a hostile or antagonistic “presence” about the place. If often wonder if Dr Mackintosh got a fright one night when he had to occupy the best bedroom unexpectedly. In the wee sma hoors a little girl in her goonie and carrying a lighted candle opened the door and came into his room. Never glancing at the bed, she lifted the carafe of water and walked out again, closing the door quietly afterwards. He certainly mentioned it at breakfast the next morning. My mother had to explain that the children knew they could always find a drink of water in the two spare bedrooms. His nocturnal visitor had been a thirsty member of the family who certainly didn’t realise that the room was occupied that night. As a child I hated the long dark passages, both upstairs and downstairs, but this is quite a natural reaction in children I find.

People with all “mod-cons” ask how we managed without piped water and no bathroom. When one is brought up without these, one can live quite comfortably. Our best bedroom had a double bed and a double washstand, with towel rails at each end. On each hung a huckaback hand towel and a terry towel. There were two oval-shaped blue and white china basins and one fat dumpy ewer for cold water. One big soap dish and two little ones and a china jar also stood on the top. This vase-shaped jar was for a gentleman’s shaving water. There were two drawers below the top surface. Under the drawers there was a little cupboard which held the chamber [po, we called it]. In the corner there was a china slop pail with a lid and a wicker handle. For hot water we had tin hot water cans. They resembled garden watering cans, but had a lid hinged in the middle. A can of hot water and the visitor’s cleaned boots or shoes were set on the mat outside their bedroom door every morning. The other spare room had a single bedroom-set, a less elaborate washstand and an enamel slop-pail, with lid. All other bedrooms had a washstand, some with a tabletop, and some with a hole cut in the top for a basin. All basins were enamel and a saucer served as a soap dish. The po always stood under the end of the bed.

There was work around the house called men’s wark and other work was exclusively wimen’s wark. One of the jobs for women was to make beds and empty the slops from basin and po. This was no-one’s favourite task, but undertaken as part of the daily round. Emptying the slops was quite a ceremony according to mother’s instructions. Armed with a large tinnie of water, a zinc bucket and a “po-cloot” we had to do the rounds of the bedrooms. First we emptied the basin and washed it out with clean water. Then we emptied the po, rinsed it out with water and wiped it clean. The slops were emptied on the middin and the pail rinsed out at the soft water barrel. The “po-cloot” was hung up on a nail on an outside wall.

There was the “peedie-hoose” – an outside W.C. or dry closet for visitors. When any member of the family was confined to bed the commode was moved to the room where it was needed. Otherwise the women and young children used the byre and the big boys and men used the stable. The upper part of the oddlers was used because younger kye banded there and there was little danger that they would annoy you. After you had relieved yourself you were supposed to cover your mess with a wisp of hay or straw. This practice always reminded me of cats scraping earth over their dirt! When the byre was cleaned all was pushed out with a big scraper through the dung hole. The stable had a little pile of dung just inside the door. This was the men’s W.C. As we grew older we had two W.C.s – one for the men, above the hoose, and one for the women, below the hoose. Now, of course, there is a flush lavatory. But during the summer of 1968 I had a most nostalgic experience. I visited the nicest, tidiest, little place I had been to for a long time. Before we left for a long drive home I asked if I could go to the bathroom. The lady of the house said, “You could pee in the byre”. I said I’d do just that. She showed me into a very clean byre with sanded floors and I felt like a bairn again!

Even if you had to answer the call of nature out in the fields you were always supposed to cover up your mess with a stone or with grass. Nowadays it seems a child must have a potty or a bathroom or have to dash wildly home before it can get relief. In the old days the call of nature was always respected. I heard a tale of a lonely little boy who never wanted to leave his playmates and go into a meal with his grown-ups. Many times when he heard his name shouted he used to pop his head above a dyke and call back, “I kinno come noo for am dirtin!” It seems this excuse was always accepted and allowed the lad to stay with his companions a bit longer.

NB: On Wednesday 3rd June 1970, my brother, David Gibson, had the old iron grate and wooden mantelpiece removed from the downstairs sitting room in Hullion. He is to install an electric fire there. When sweeping the chimney before boarding it up he discovered a large iron hook firmly imbedded in the back wall of the chimney. To remove it would have damaged the wall, so it was left there. My sister tells me that this room was at one time the kitchen and must have had an open hearth fire.

The building now covered with ivy at Hullion was one of the early two storey houses in Rousay [known as Holland]. It had only two rooms. The downstairs room had a big open hearth and the upstairs one a tiny fireplace and a very small window. There was an outside stone stairway that led to the upper room. Built into this stairway was a recess, which I’m told was a peat-neuk.

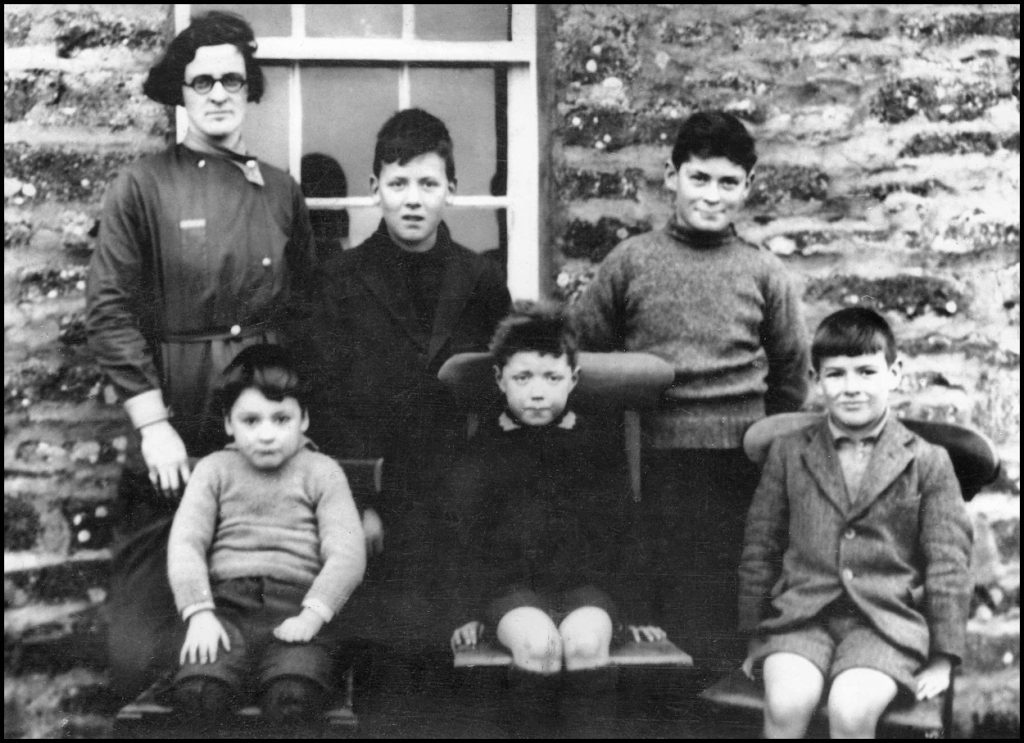

In the mid-1930s Kitto was the teacher at Frotoft school, at which time there were just six pupils – one of whom was her brother Dave. Two of the other pupils were John Mainland and his sister Sheila of Nears. My thanks to Sheila for allowing me to reproduce her memories of those Frotoft schooldays.

Kitto with her pupils in 1936: Ronald Stevenson and Dave Gibson, and in front:

Harry Marwick, John Mainland and Jimmy Pirie. Unfortunately Sheila

had left the school by the time the photo was taken.

[Photo courtesy of Tommy Gibson]

“When I started at Frotoft school there were only six other children. One, Ronald Stevenson, left after three months and another, Dave Gibson, after six. Dave’s sister, Kathleen was the teacher throughout my time at school. She became Mrs. Harcus when I was 12. As the oldest pupil at that time it fell to me to present her with the wedding gift from the pupils. She cycled over from Hullion every morning and we would watch as she went past the window trying to judge by her expression what kind of mood she was in.

The day always started with the Lord’s prayer followed by copybook time using pen and ink. We had a cup of cocoa at peedie playtime and kept our piece for the longer break. Playtime games included rounders, football and picko. On wet days we played marbles and ‘Pussy wants a corner’ in the boys’ lobby.

The teacher’s desk had two compartments which we never got the chance of looking into. We knew the strap was kept in one of them for it was frequently brought out and used. Sometimes it was left on the desktop to act as a warning. Another thing that was kept in the desk was a set of mental arithmetic cards. The teacher sometimes took us out to the floor and asked us questions from these cards. The strap would have been preferable!

The highlight of the school year was the picnic held at the end of June. Everybody in the district attended, old and young. I cannot remember a picnic day when the sun did not shine. The grown-ups enjoyed watching the children’s races, and some of the youngsters’ fun came from watching their elders making fools of themselves at the wheelbarrow, sack, and thread-the-needle races. The dance that always followed the picnic was always a lively affair with all ages joining in. The old ladies would enjoy watching the latest romance and who was dancing with whom, and how often. Dresses old and new would be commented on. Supper was served as darkness fell and the oil lamps were lit.

The school cleaner had the task of emptying the bucket from the girls’ toilet several times during the evening and from time to time she sent me out to take a look and report back if it was time for another trip to the midden.”