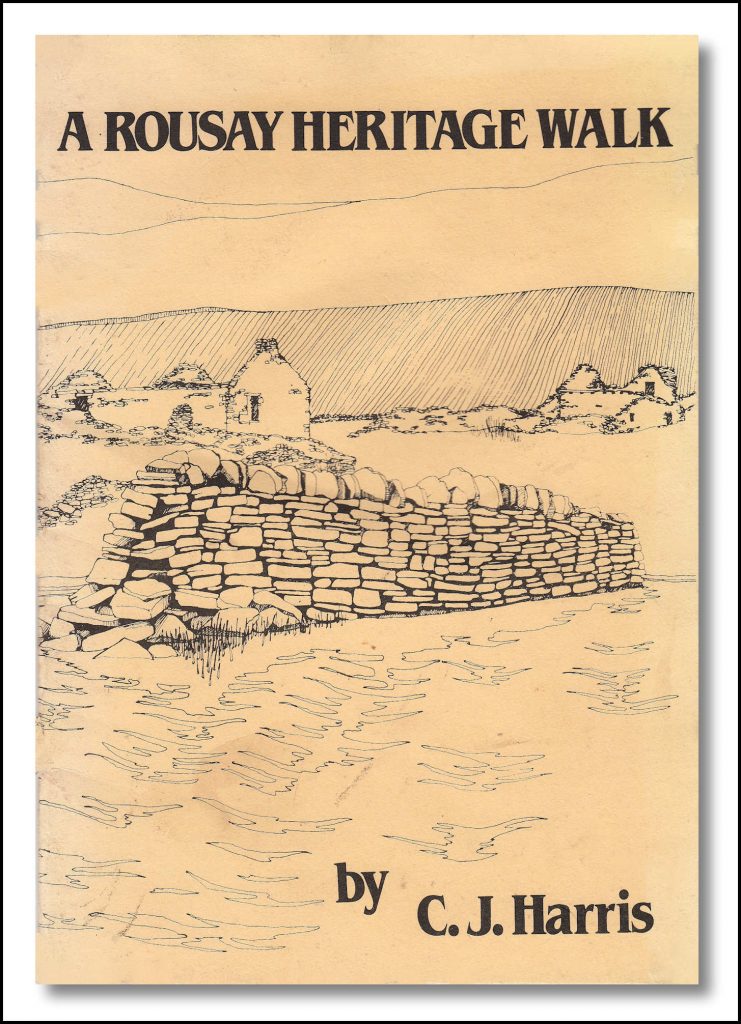

A Rousay Heritage Walk

by

Christopher J. Harris

Published by The Orkney Pottery, Rousay, Orkney, in 1978

and reproduced here with the author’s permission.

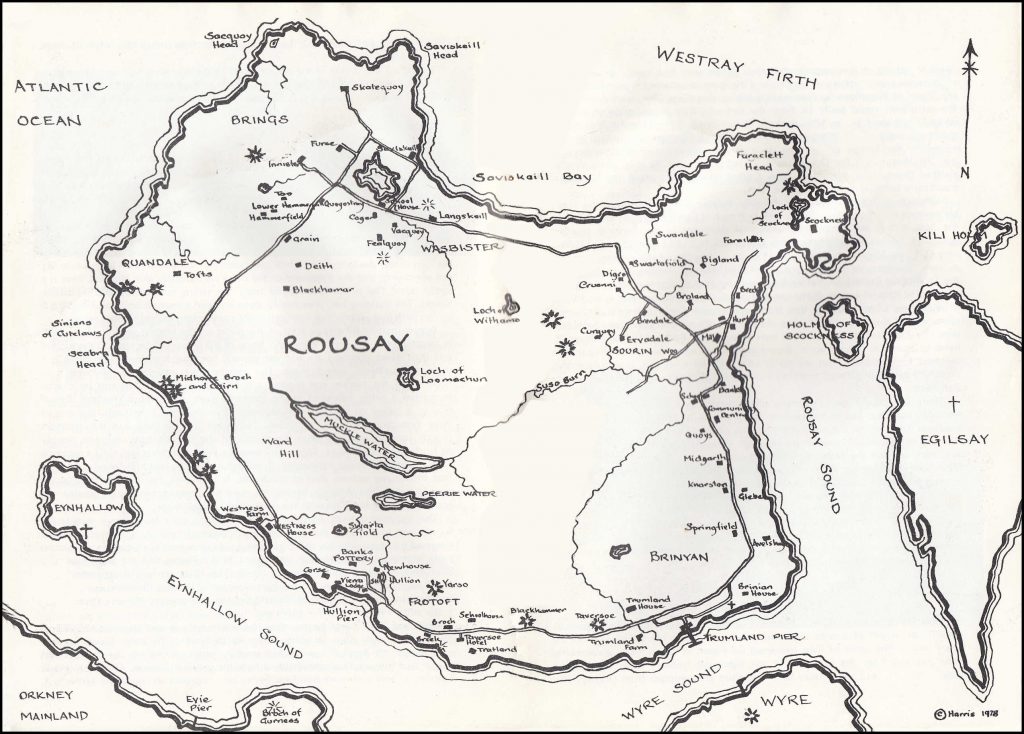

Most visitors come to Orkney to admire the natural beauty of the Islands and see their rich heritage of ancient monuments. Nowhere can these features be better combined than in Rousay, looked upon by many Orcadians themselves as the most picturesque of the Orkney Islands. The Island, a mere 18 sq. miles, encompasses most types of scenery, from high cliffs with their teeming bird life, to sandy beaches edging good arable land. After Hoy, Rousay has the highest hills in Orkney and they have supplied peat to the Islanders for many centuries as well as being rough pasture for sheep and at one time for cattle. The division between the arable land and the outrun is still clearly visible as the hill-dyke, a turf and stone hill wall which runs round most of the Island between 200-250 ft. contours. Above the dyke many old peat cuttings can be seen from the boat as you sail towards the Rousay pier from the Mainland.

Rousay is like a living history book of the Orkneys with something to illustrate each chapter of settlement from the Stone Age to the present day “Ferryloupers”, or Southerners who have settled here. An Orkney historian, the late J. Storer Clouston, said “There is no corner of Orkney more steeped in history than this parish with its four Islands of Rousay, Egilsay, Eynhallow, and Wyre. Every one of them comes into the Sagas, and on each something more than usually eventful happened”. This little booklet is not meant as a history of the parish nor a comprehensive guide to the Island but just a guide to some of the places of interest which can be seen on a day tour to Rousay. We believe that the walk described is one of the most remarkable that can be made into Orkney’s past and hope that these few pages help your understanding and enjoyment of it.

The Department of the Environment’s Guide to Ancient Monuments in Orkney is a great asset on any tour in Orkney and ought to be bought before crossing to Rousay.

Information about transport to the Island is to be found elsewhere in this booklet.

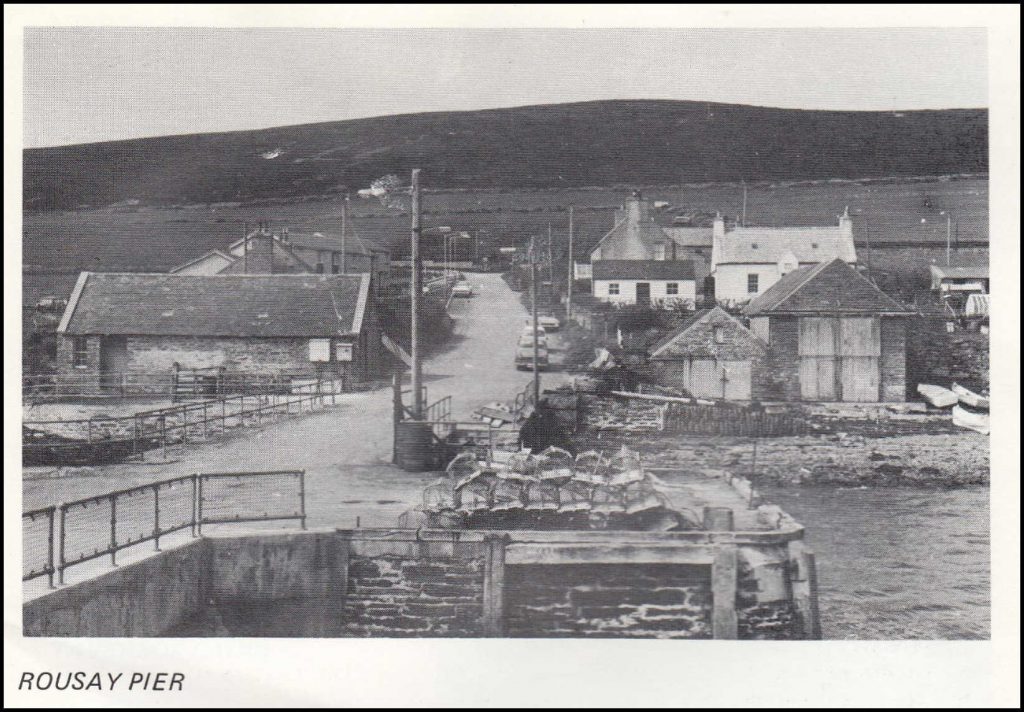

The tour, which will take us from the main pier, opposite Wyre, to Scabra Head in the West, follows the public road for most of the way and you can see where it runs as you sail round the skerries and enter Wyre Sound en route for Trumland Pier. The crossing looks innocent enough but the strong currents in Eynhallow Sound are very much respected by the boatmen and are still a hindrance to communications when wind against tide produces rough water.

PIER AREA – TRUMLAND HOUSE

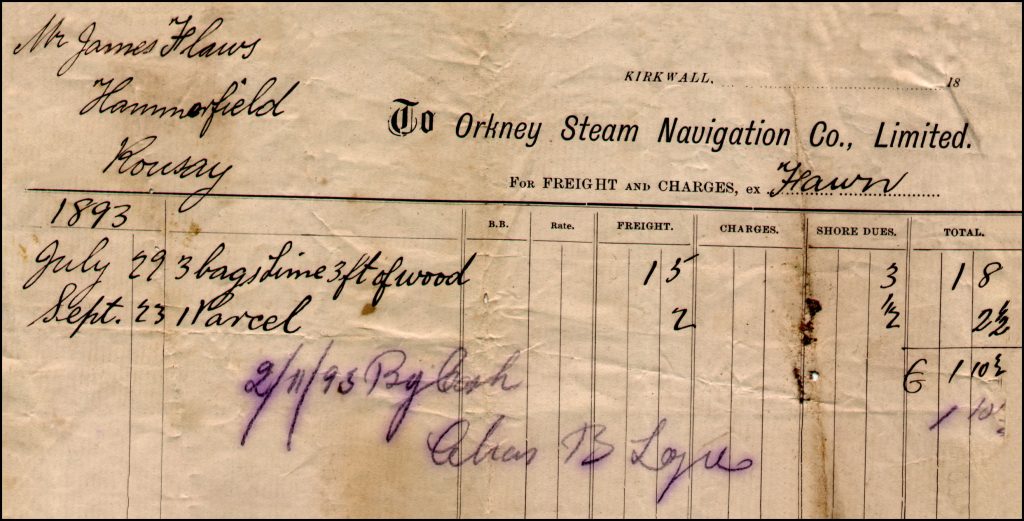

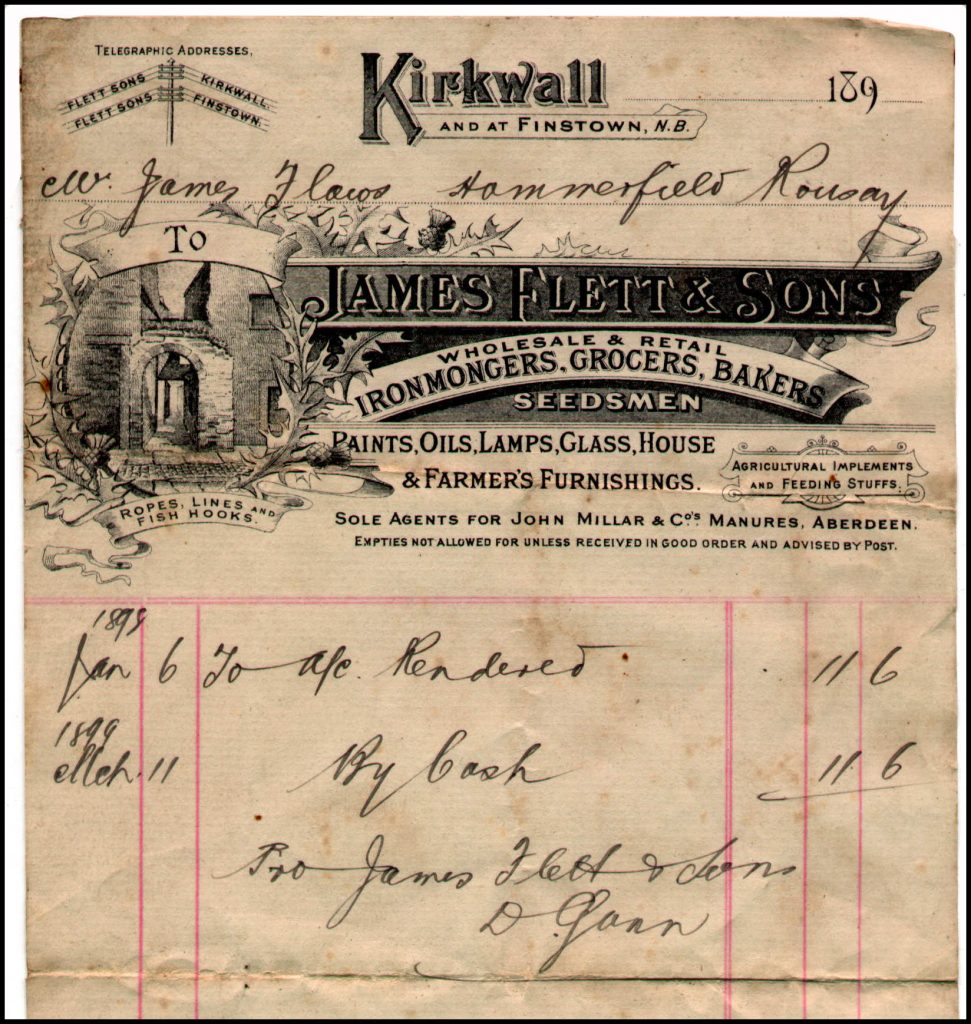

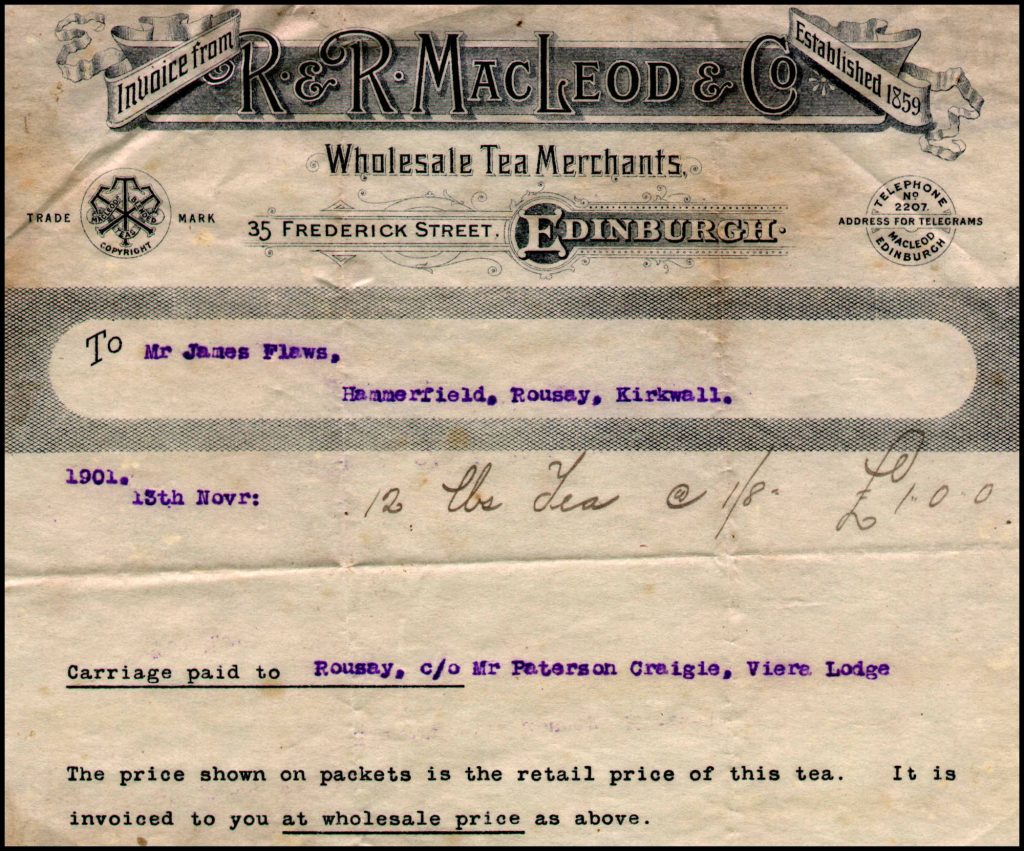

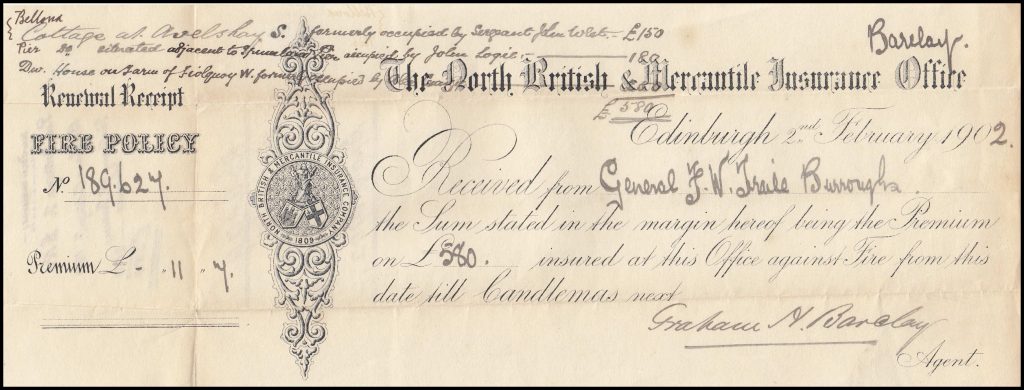

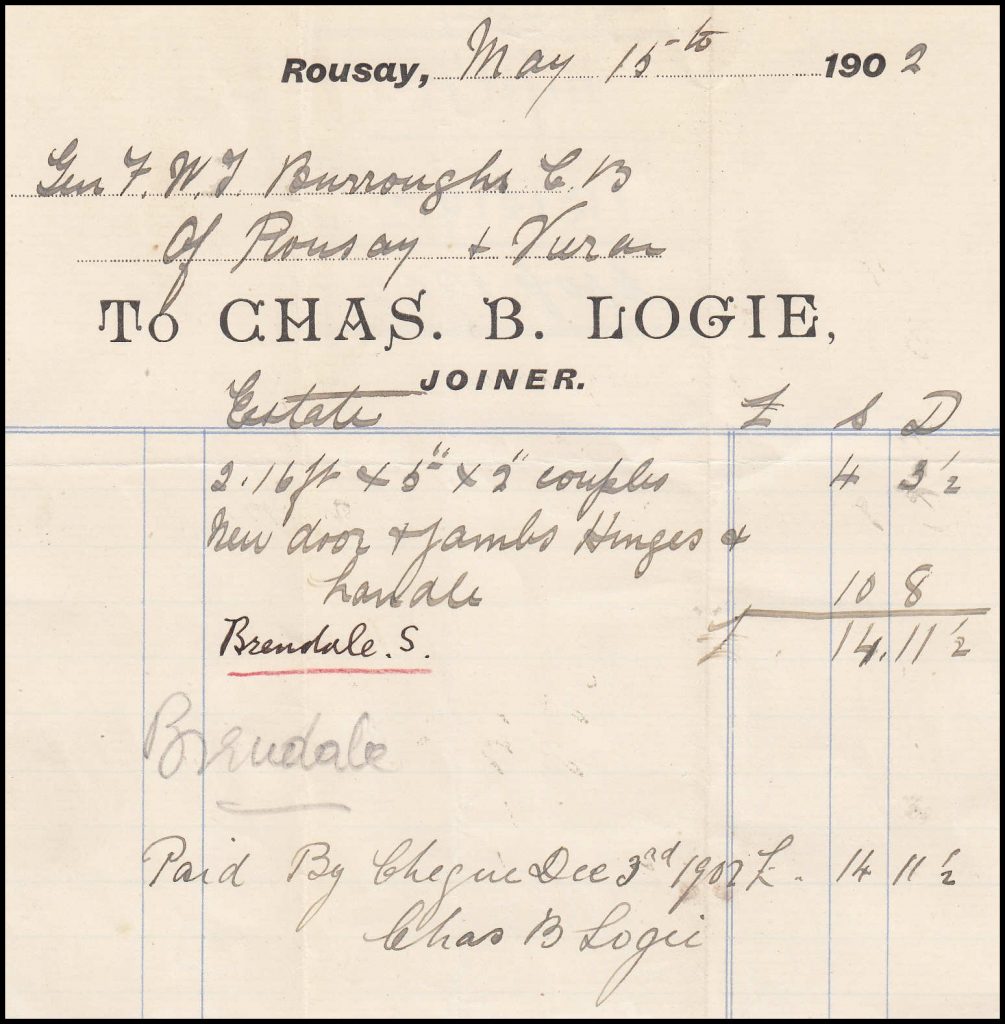

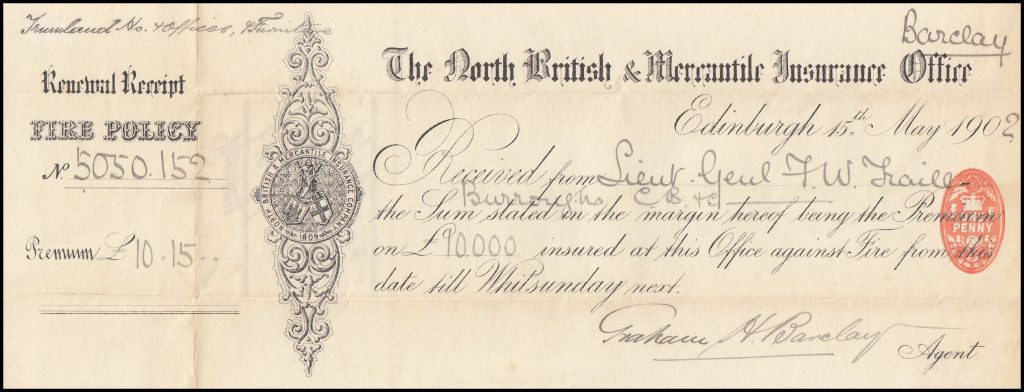

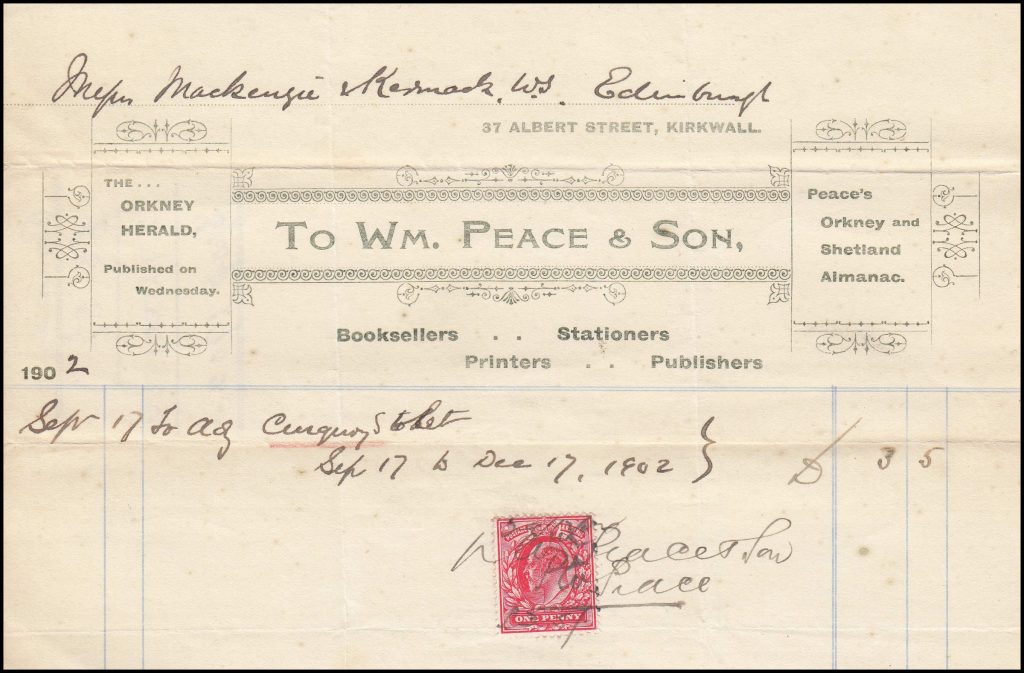

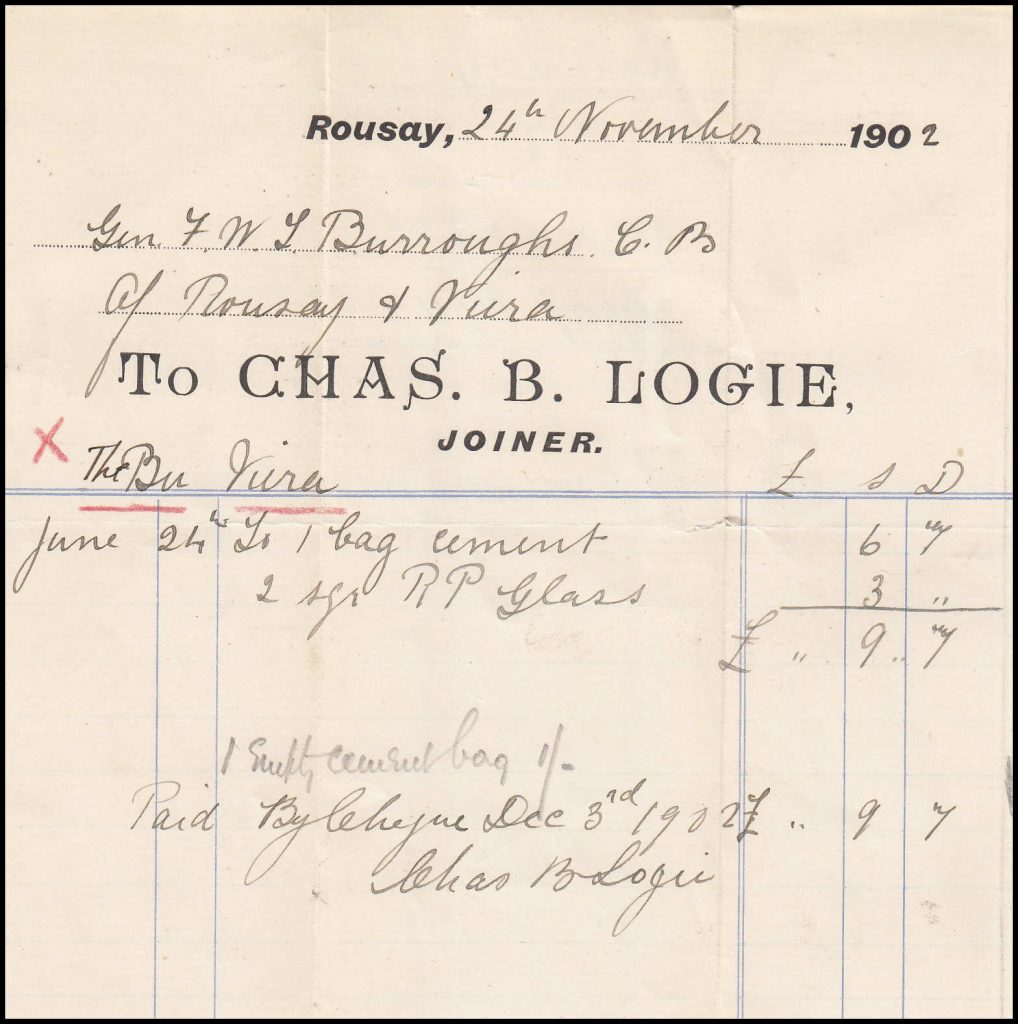

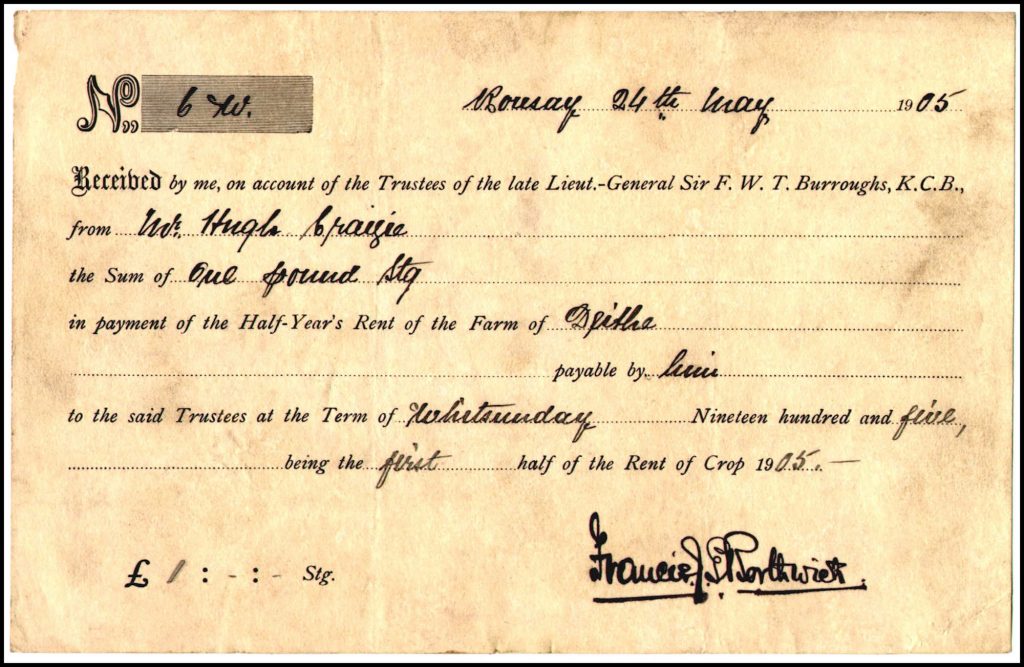

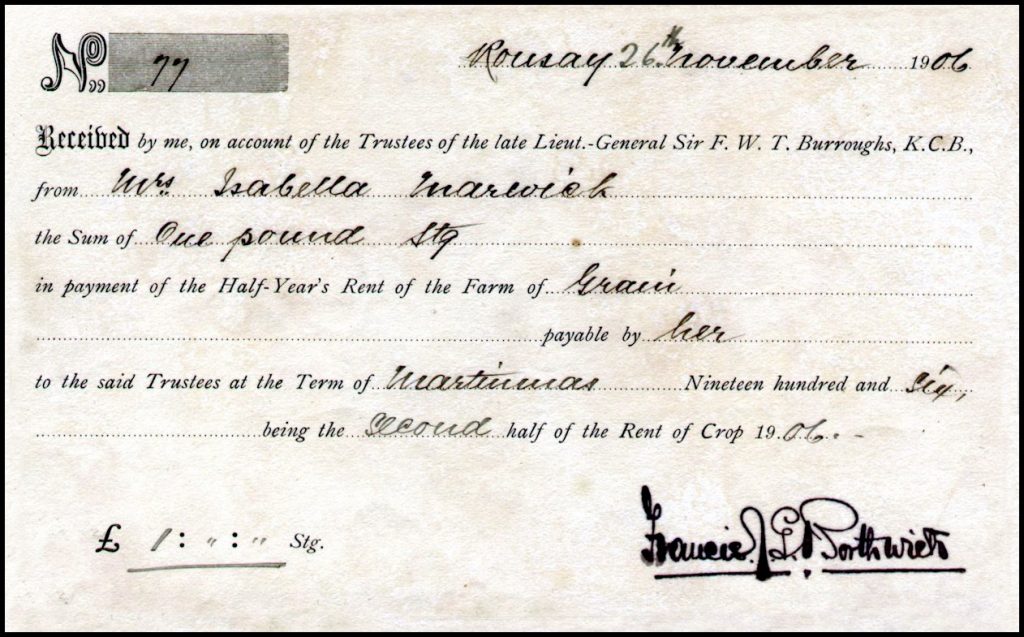

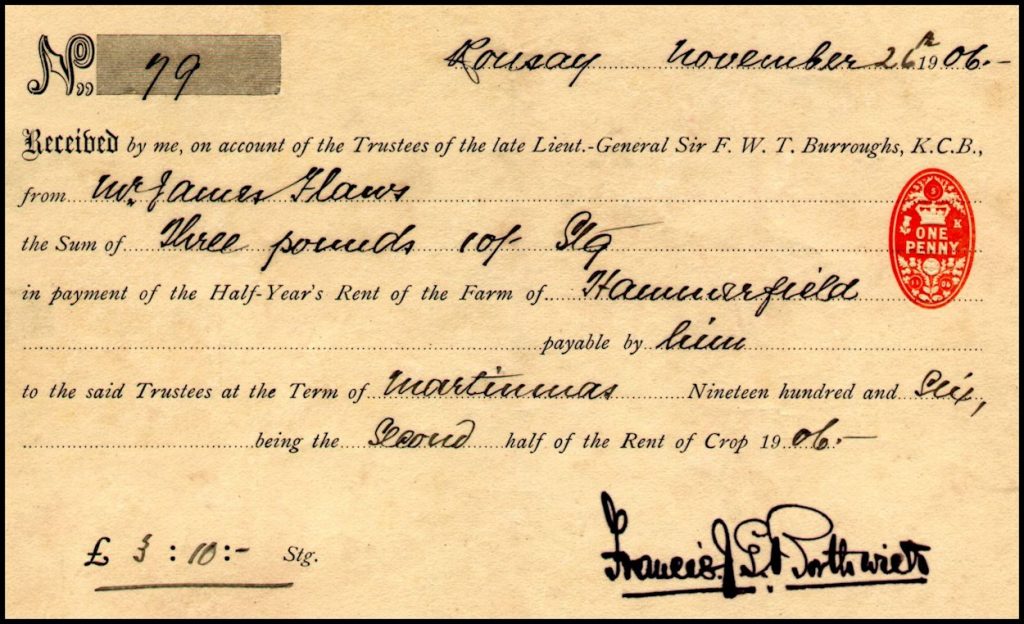

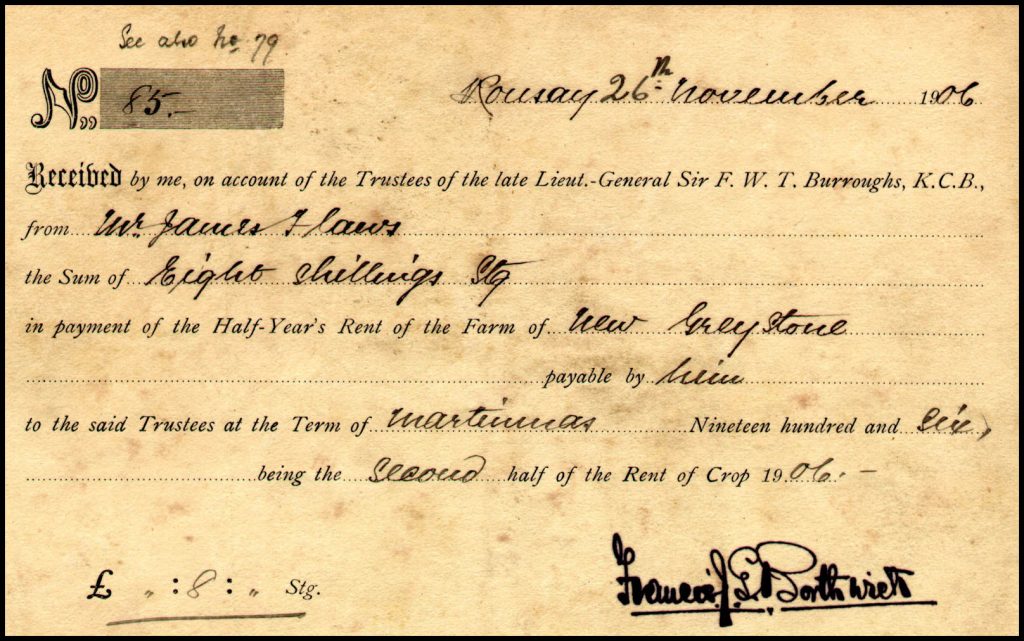

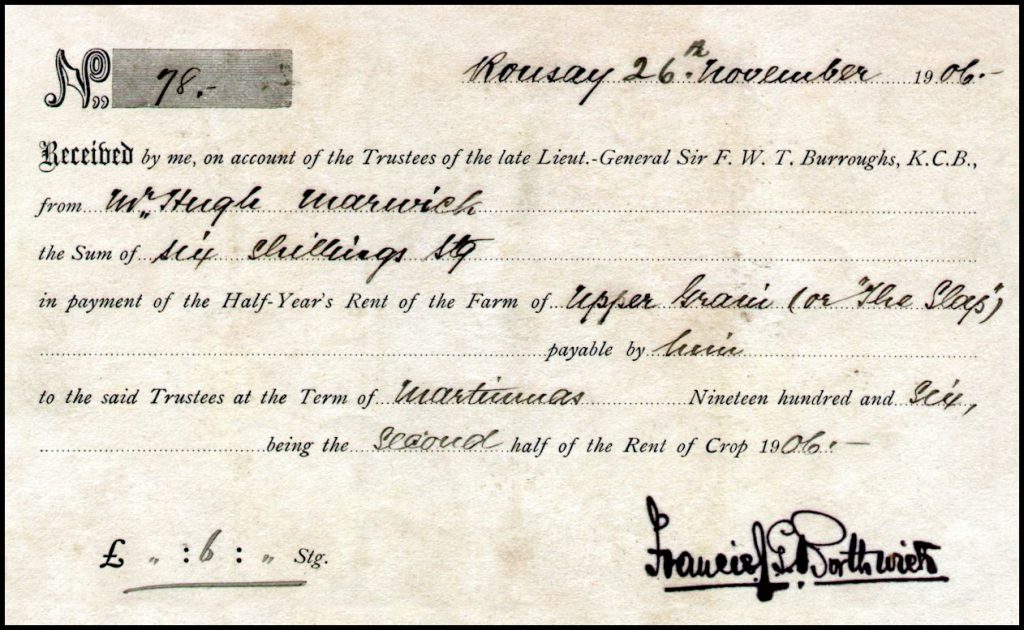

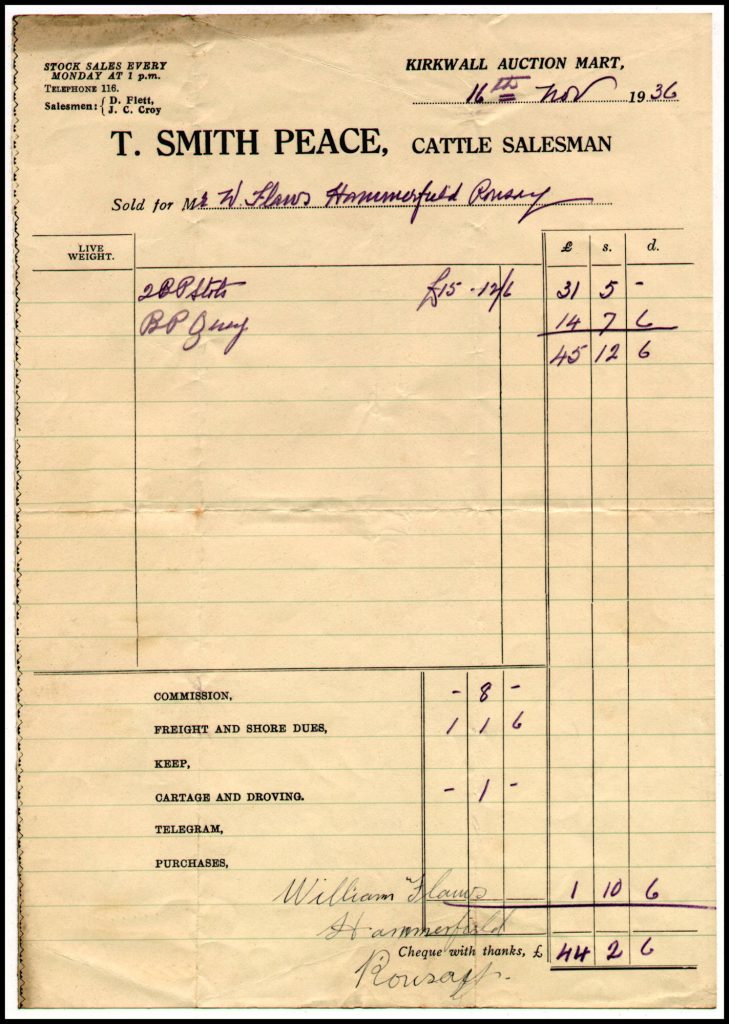

The pier has just been extended to allow the inter-island cargo boat to call once a week at any tide. The original pier can be seen, and it was built in the 1870’s by the largest proprietor in the Island – General Traill Burroughs of Trumland House. He was the largest shareholder in the first steamboat company for these Northern Isles, and the “Lizzie Burroughs” plied a regular service from this pier, enabling him to ship sheep and cattle to market with relative ease. The larger of the two boathouses at the right hand side of the pier housed Burroughs’ private yacht and his boatman lived in “Pier Cottage” built in 1877. “Ivy Cottage”, a little nearer the Kirk was built in 1878 for his joiner.

Burroughs is a figure we shall recall several times during our tour.

Perhaps one of the first buildings to catch your eye to the left above the pier will be the Rousay Fish Processing Factory which processes shell-fish. It is a cooperative, owned by many of the Islanders who employ a manager to run it for them. The workers are men and women from within the parish and their numbers vary according to the season. Much of the product is exported to the Continent.

To the right of the telephone kiosk and adjacent to Pier Cottage is one of the Island’s two shops. We shall pass the other one later.

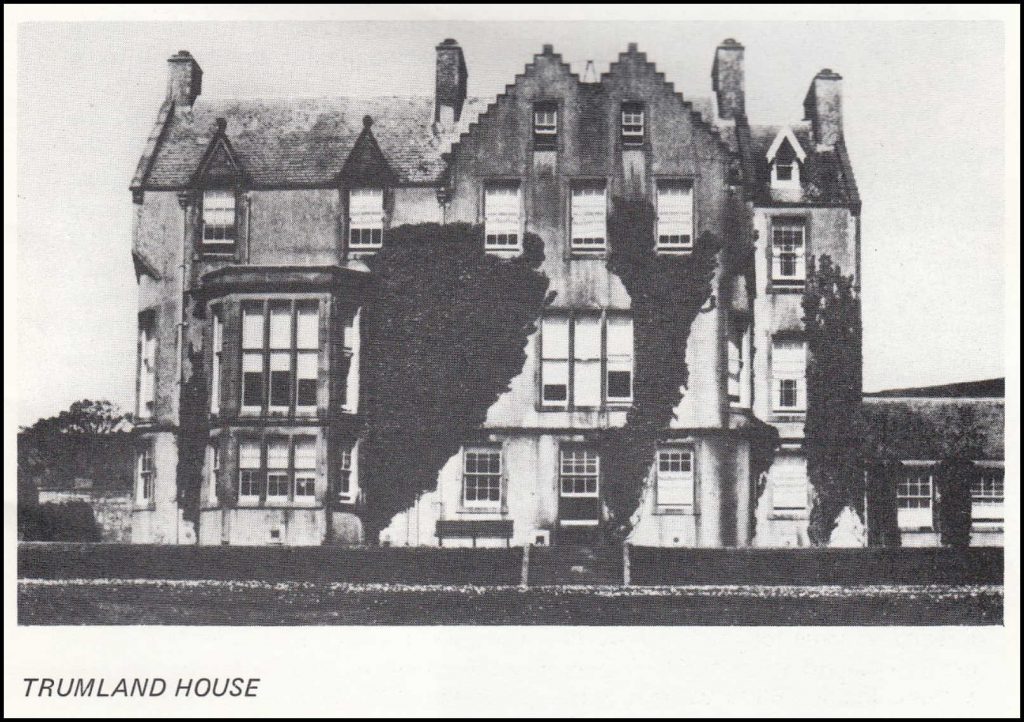

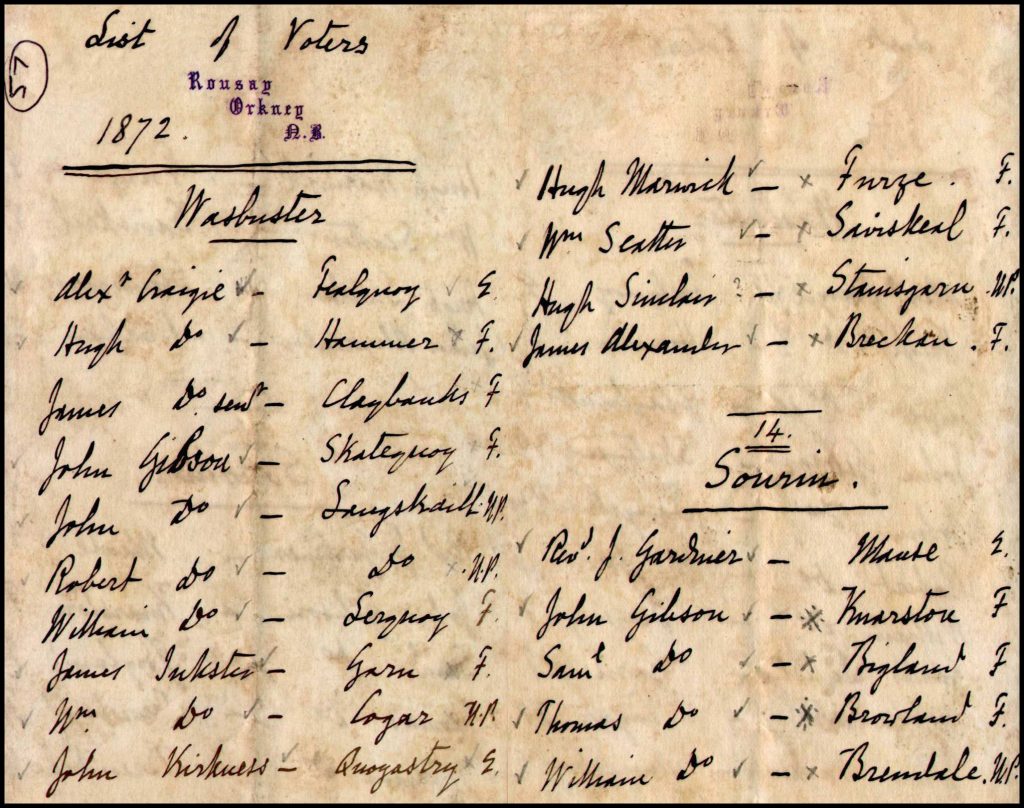

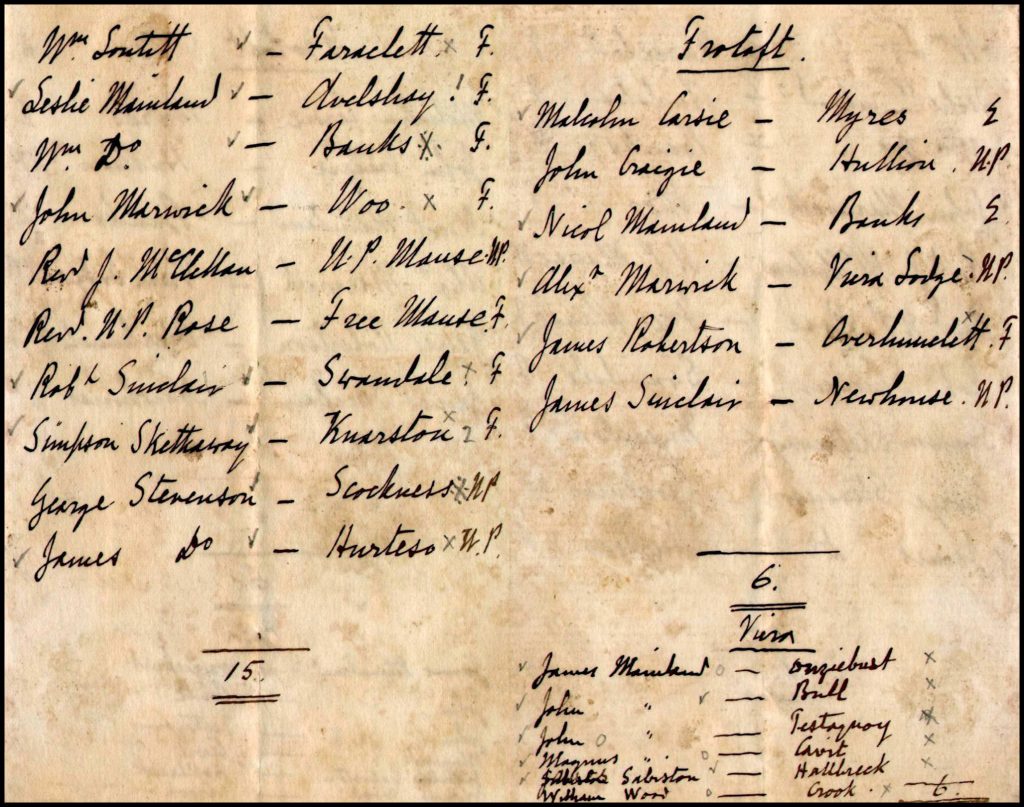

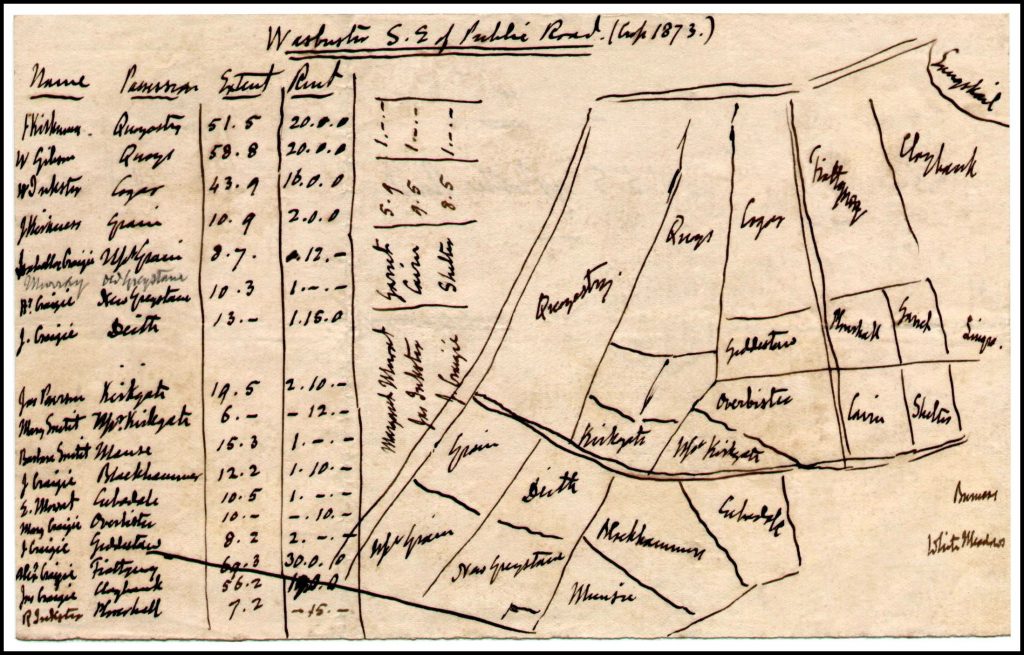

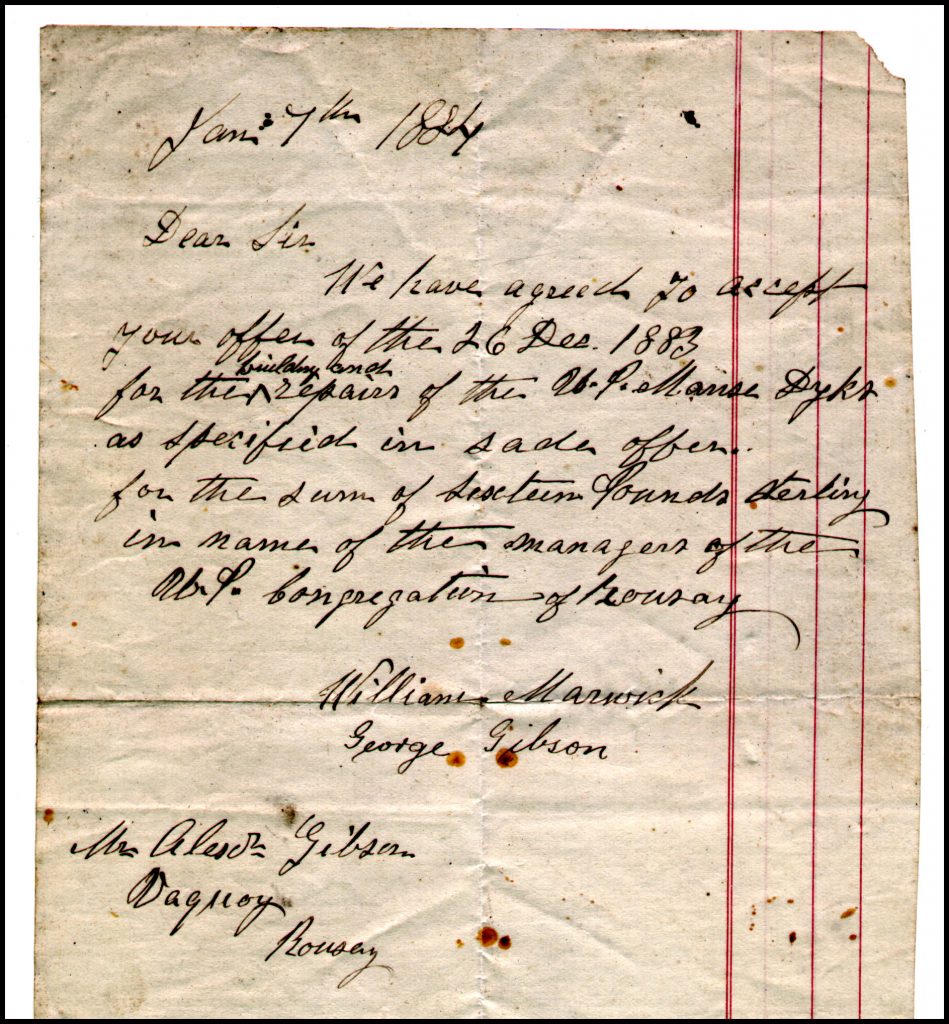

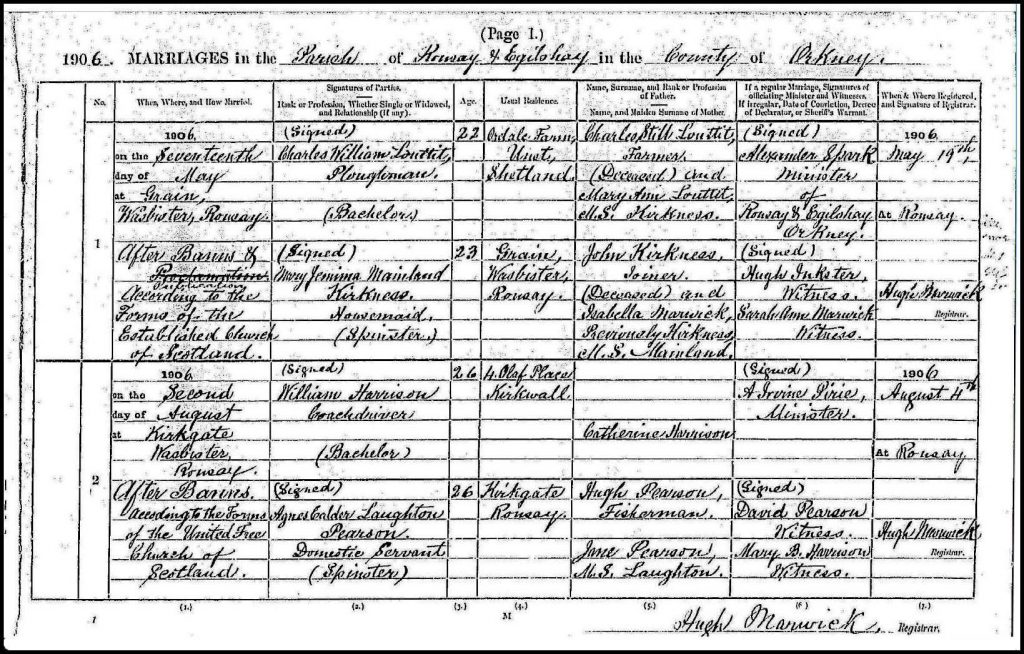

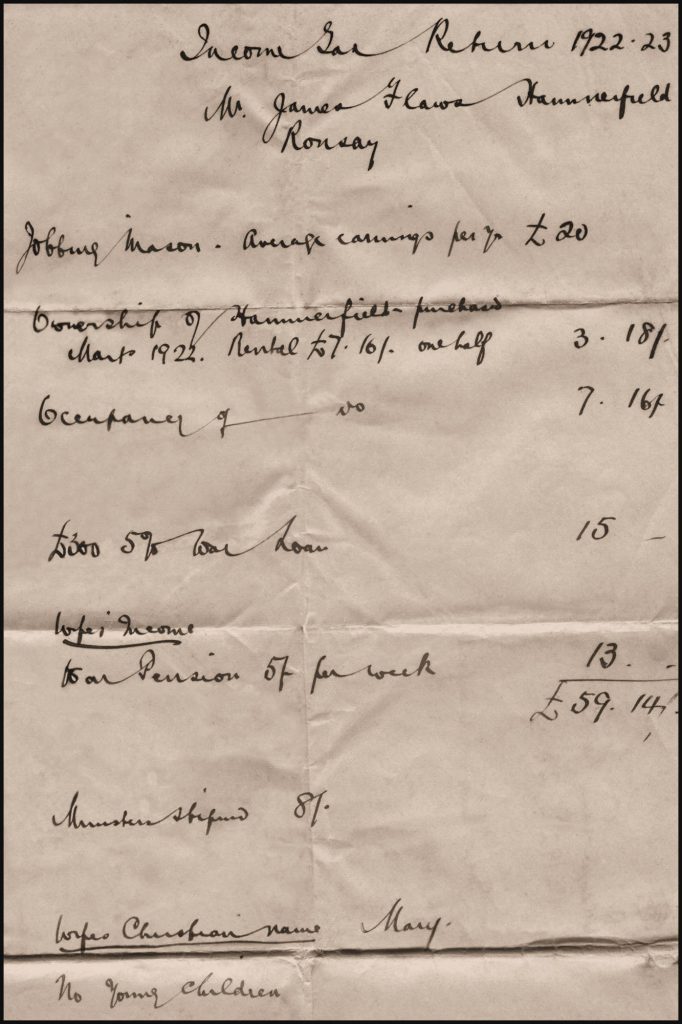

Continuing up the road we turn left at the War Memorial and walk up to the “main” road and the entrance to Trumland House. This imposing mansion, which is private property, comes as quite a surprise to most folk as it looms up from the low woodland round it. It was designed in Scottish baronial style by David Bryce who was the architect for the larger Balfour Castle in Shapinsay. Trumland House was built in 1873 for General Traill Burroughs. When he married he thought his previous residence, Westness House, too small for the largest landowner in Rousay. Burroughs had inherited the estate from his grand uncle, George Traill, in the middle of the century. Traill had made his fortune in the Indian Civil Service and on his return to Britain had bought the estate. Burroughs, too, did service in India where he commanded the 93rd. Sutherland Highlanders. These two men consolidated their fortunes and positions by the so-called land “Improvements” which made them notorious in the Islands and brought on Burroughs’ head the wrath of two Royal Commissions on Crofting. Both men evicted tenants from parts of the estate in order to make larger farms for the new Cheviot and Leicester-cross sheep and Shorthorn cattle. The old self-sufficiency of the crofters was being replaced by a market economy and it was this which lay behind the “improvements”. It is easy with hindsight to condemn Traill and Burroughs for the Rousay evictions but in their class it was thought to be the only way to improve everybody’s lot. They saw the abolition of the run-rig field system, the enclosures of land and a more intensive utilisation of it as a way of generally improving everyone’s standard of living. If some folk had to leave their homes and adopt a whole new way of life then it was said to be for their own good. Traill was responsible for the cruellest evictions in the 1840’s whereas Burroughs preferred “to leave the people in their houses and make them labourers,” as he said. When his tenants objected he told the Crofters Commission that “they all want to be masters and not servants, and that is impossible”. Despite their pronounced good intentions there is no doubt that these two landowners caused great hardship in Rousay and indeed completely changed the way of life of the Islanders. Trumland House stands here as a stark memorial to “the little General” who was even condemned by the other land-owners in Orkney.

It was this mansion that became the home of the late Walter Grant, Director of the Highland Park Distillery in Kirkwall and perhaps the greatest private benefactor ever to Scottish Archaeology. Most of the large monuments we shall visit were excavated at his expense by such well known archaeologists as Callender and Professor Gordon Childe.

Continuing along the road we come to the bridge, with Trumland Farm on the left. If you go through the small gate on the right of the bridge you can take the Burnside Walk, a pleasant path through the trees. At the other end of this path you come out into an open field across which our first monument can be seen. If you do not wish to take the walk through this delightful wood, you can keep to the road until you see the sign directing you to Taversoe, our first stop.

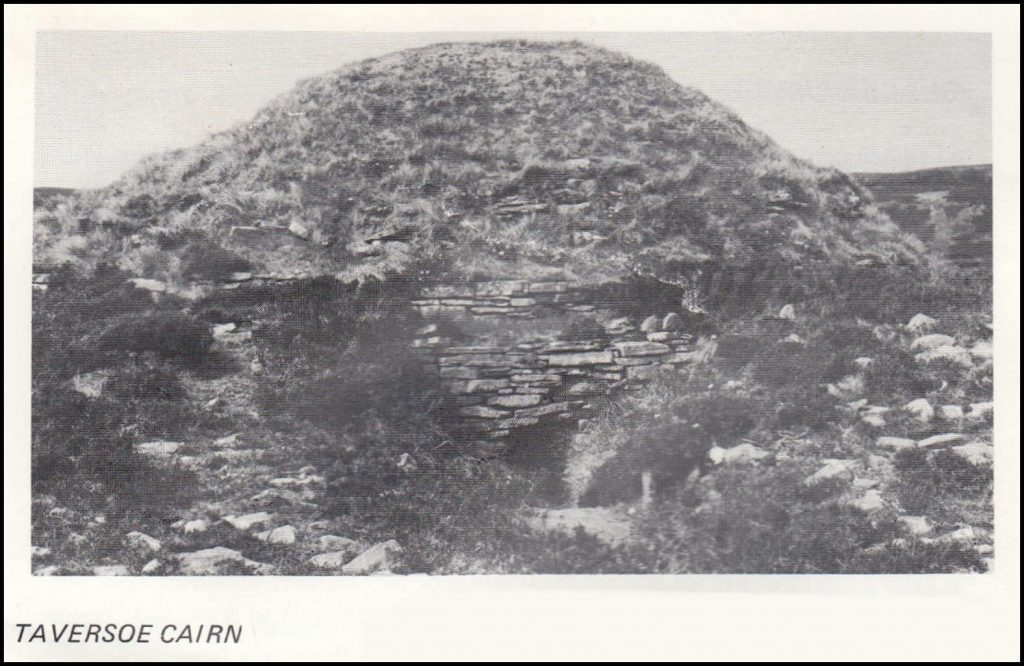

TAVERSOE

This is the first chambered cairn on our walk. Like most of the Rousay place names, Taversoe is derived from the Old Norse but apart from the final syllable, most likely derived from Old Norse “haugr” meaning mound, this name is some-what of a mystery.

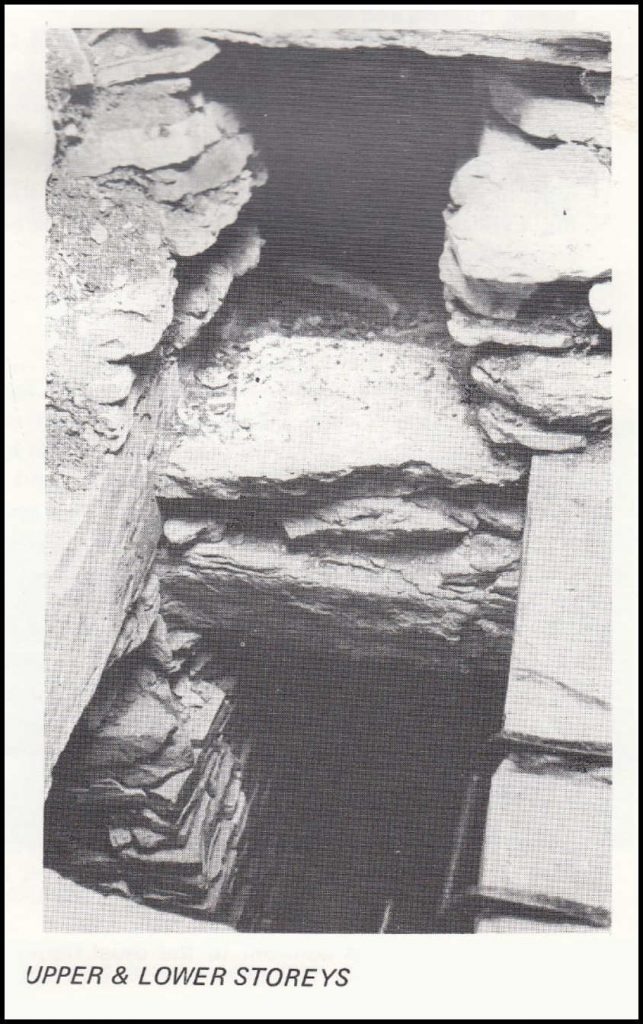

This remarkable cairn was first discovered when Lady Burroughs decided the spot was an admirable place on which to erect a “lookout” seat in 1898. The merits of the site had attracted man almost 5,000 years previously when a two storeyed cairn was here. There is an explanatory plaque at the site and a good description in the Orkney Ancient Monuments Guide. It is interesting to note that from the top of this tomb it would have been possible to see the tomb of Blackhammer to the West. When that was noted, Gordon Childe pointed out that most of the Rousay tombs stood on the edge of terraces, overlooking the coastal land where the builders presumably had their fields. Even today we can see that each tomb or group of tombs clearly corresponds to a natural settlement unit with a freshwater supply, arable land below and pastures above. The present day concentrations of the population in Rousay are almost identical to those of the Stone Age Rousay when these first farmers arrived from the South. The notable exceptions are those areas where the farmers were evicted in the last century.

After admiring both the monument and the view we continue along the road to a different type of tomb, the Blackhammer Chambered Cairn.

BLACKHAMMER

Hammer is presumably from the Old Norse “hamarr” meaning projecting rocks or cliff. Although presumed to be of a similar age (about 3,000 B.C.) this cairn is of a different construction which must reflect the builders’ different traditions or customs from their neighbours. This so called stalled-cairn contained only two burials with grave goods such as pottery, an axe-head and a flint knife. Why was so much energy used to build such a tomb which was only used twice? Were mound burials replaced by another burial custom? Were these the tombs of a ruling class – the Chieftains of a farming community or were they community tombs? These are just a few of the questions which archaeologists have speculated over for years. The sheer size the Rousay burial cairns makes one thing quite clear however: they were either built by a society whose farming methods created a surplus of time during which the tombs could be erected, or else they were built by a people with a dominant belief in the after life. The amount of time spent tomb building could so easily have been to the detriment of their food-gathering activities: fishing, hunting and farming.

Before leaving the Blackhammer cairn look down towards the shore, about a quarter of a mile east of the farm of Nears. Here there is a large turf-covered mound known as the Knowe of Hunclett. Hunclett is the name of the Norse township and probably means a place of many stones or stoney place.

The original head house of the township has never been identified but it seems most likely that it is not this which is under the Knowe but a Broch. The shores of the Eynhallow Sound are dotted with these Broch remains but few have been archaeologically investigated.

YARSO

Not far along the road from Blackhammer is the sign for the turn off to Yarso, the third of the Rousay Cairns under the guardianship of the Department of the Environment. It takes about 15 minutes to reach but as the path is badly marked it may take a little longer and many people find that they have not the time to visit the highest of the large Rousay cairns. It can be seen from the road on the edge of a small cliff, about 300 ft. above sea level, and is a good viewpoint for those who make the effort to visit it. Yarso means “mound of the edge” from the Norse “Jadarr” = edge, “Haugr” mound. It is a cairn of similar construction to Midhowe which we shall visit later, but much smaller. Despite its size it contained the bones of 21 humans, along with those of a dog, sheep and many red deer.

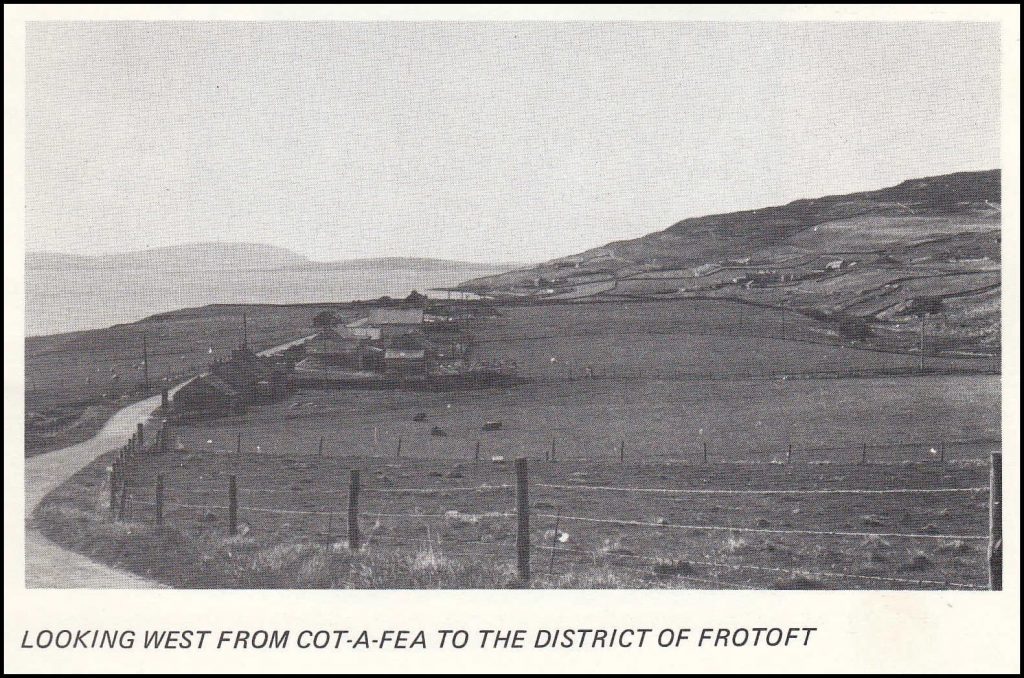

This cairn is just one of the several large tombs overlooking the fertile district of Frotoft which must have been densely populated already in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, several thousand years ago. However, after retracing our steps to the road, just before we reach the road, on the left we pass the old Frotoft School, now converted into a comfortable home. We turn right along the road. After a few paces, on the left, is the one and only pub in Rousay, the new Taversoe Hotel. Here one can obtain sandwiches or a Bar lunch in addition to the usual liquid refreshments. It is a very friendly and convenient place to stop for a break in our walk.

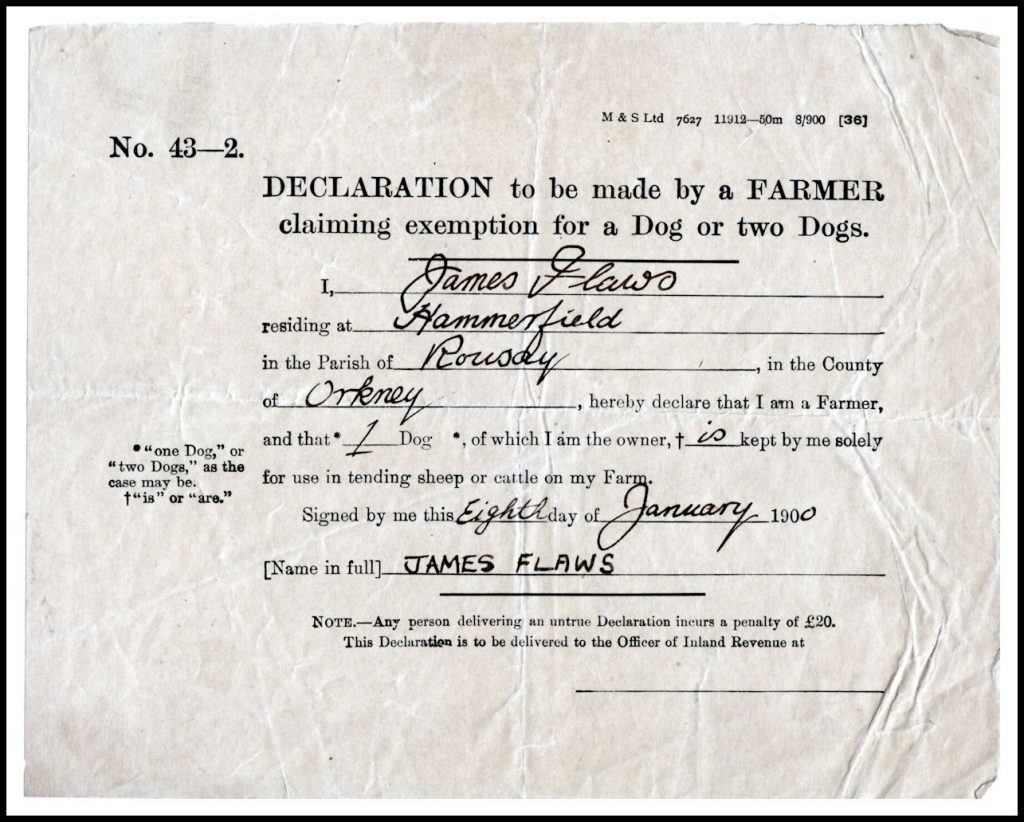

From the pub it is just over three miles to our next “official” monument, but there are many places of interest on the way, and after visiting the prehistoric Neolithic tombs we now pass into the historical times, going down the Cot-a-fea brae into the Norse township of Frotoft. There is one last monument here from the distant past and that is the standing-stone which is at the roadside, at the end of the croft as we go down the hill. This croft has taken its name from the “longsteen” or “langstane”. The Longsteen is nearly seven and a half feet high and two feet three inches broad at the base. It is only one of many Standing-Stones in Orkney and exactly when they were built and to what purpose is a mystery. The crofts we pass on the roadside here bear the names Langstane, Cott, Broch, Burrian and Breek, in that order. Apart from names the crofts also have numbers, an unusual feature in Rousay and indicating clearly that they were erected to a plan. These are some of the crofts which were built in the 1840’s by those folk who were evicted from the Quandale district we shall see at the end of the tour. The least fortunate crofters had to either build outside the hill dyke or to leave the Island, but here in Frotoft a small number of buildings were erected along the new road.

The croft called ‘Broch’, No. 3 Frotoft, is certainly one of the most picturesque of the Rousay crofts, and very typical of the “improved” buildings of the last century. One of the innovations of the “improved” croft was the gable fireplace with chimney, whereas the traditional Orkney croft had an open hearth near the centre of the room with a smoke outlet in the roof.

BROCH – BREEK – HULLION

The names Broch and Burrian are taken from yet another unexplored Broch, the Knowe of Burrian, which is at the shore edge some 50 yards west of Langstane and can be seen as a mound if one looks down towards the shore. Further along the road we come to another croft in Frotoft called Breek. Although uninhabited it is interesting to know that there are still folk on the Island who used to live here.

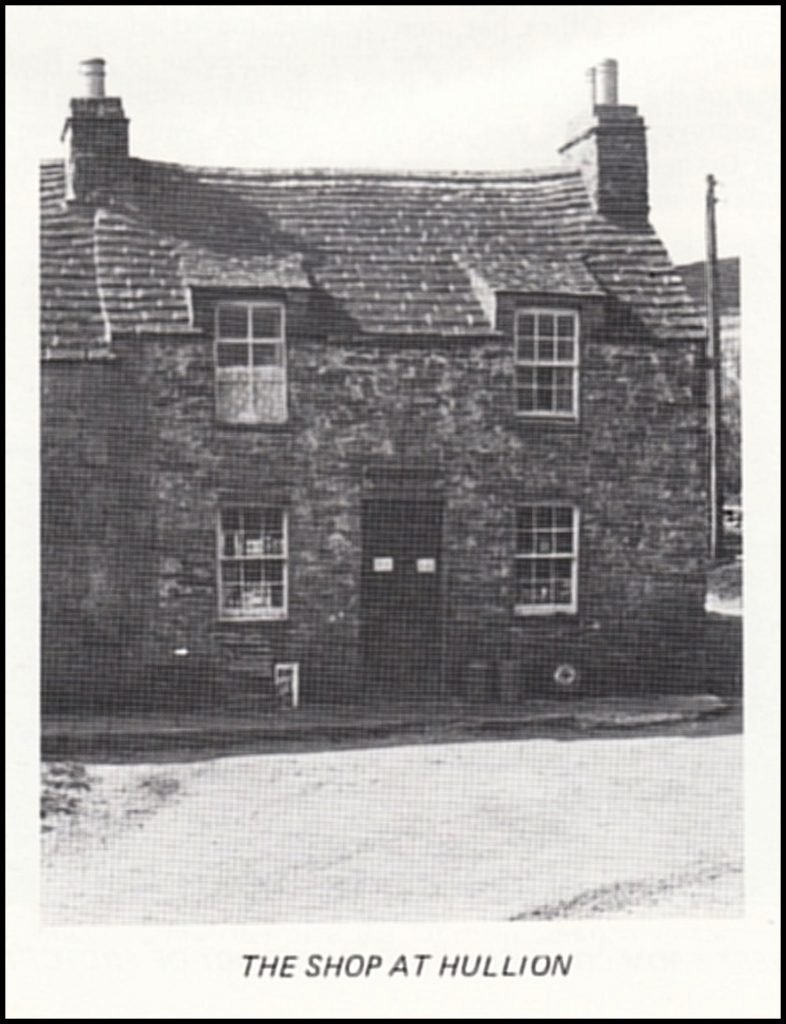

Moving along the road we come to the telephone kiosk and if we turn right we come to Hullion, Newhouse and two other crofts. “Going to Hullion” in Rousay, means a visit to the shop or the Island’s only petrol pump. The house itself is a beautiful two-storeyed building of uncertain age but certainly not younger than the late eighteenth century and maybe considerably older. Some of the buildings nearby have the unmistakable air of antiquity but until the domestic architecture of the Northern Isles has been investigated, their age remains uncertain. It is very tempting to derive the name Hullion from “the Hall” and to associate it with the site of the Norse head-house of Frotoft. Certainly the main Norse settlement would be in this area with a good freshwater supply, arable land and a notable bay near the present Hullion pier into which the boats could be pulled. Other evidence also points to this site as being one of a major Norse settlement, not least the local tradition which called the field east of the pier the Chapel Field, the mound of which can be clearly seen. The late Dr. Hugh Marwick and J. S. Clouston pointed out that the main Norse halls each appear to have had their own private Chapels, some later becoming parish churches but many others falling out of use and existing only in local tradition today.

There is much written about the buildings in Frotoft but there is only room here for a few general remarks. From Hullion we continue on the main road, past the Chapel Field and the turning down on the left to Hullion pier. For many years this was the pier for the mail-boat, and this crossing is also the shortest to the Mainland. Immediately opposite the pier, on the Mainland, is the Broch of Gurness, which is the second of the Orkney Brochs under the Guardianship of the Department of Environment. From the very sharp S-bend in the road we can look back up towards the Yarso cairn which is clearly seen from here on the edge of a small cliff.

BANKS

The next croft on the right hand side of the road is called Banks (from old Norse “Bakkar” steepish slopes) and this was the largest property in the district at the beginning of the seventeenth century. The name Banks was often used instead of the older name Frotoft. Today it is workshops of The Orkney Pottery. (visitors are welcome).

The large two-storeyed house on the left near the shore is Viera Lodge. This was once the home of the Factor for the Burroughs estate and later became a guest-house. There is yet another Broch-mound immediately to the West of the house at the very edge of the shore. Once again we are reminded of the continuity of the settlement from prehistoric times to the present.

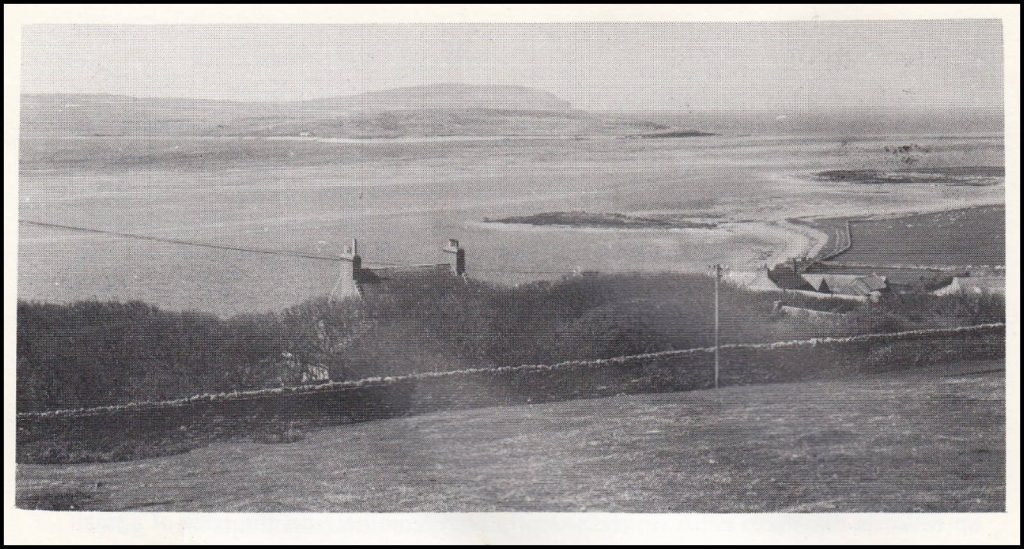

Almost at the top of the incline, as the road rises, is the croft called Corse. It is the boundary between Frotoft and Westness, or the Westside, and the name tells us that at one time there was a wayside cross or prayer stone here. Such crosses were common in Catholic times and were erected on sites where a Holy place came into view. There are many preserved, especially round the Cathedral cities of Britain but others remain only in tradition of place-names. There was a double reason for such a wayside cross at Corse because both the parish church at Skaill, which we shall see, and the monastic settlement on Eynhallow came into view. From Corse we can look back over the populous, thriving community of Frotoft and then look Westwards over the depopulated Westside so cruelly cleared.

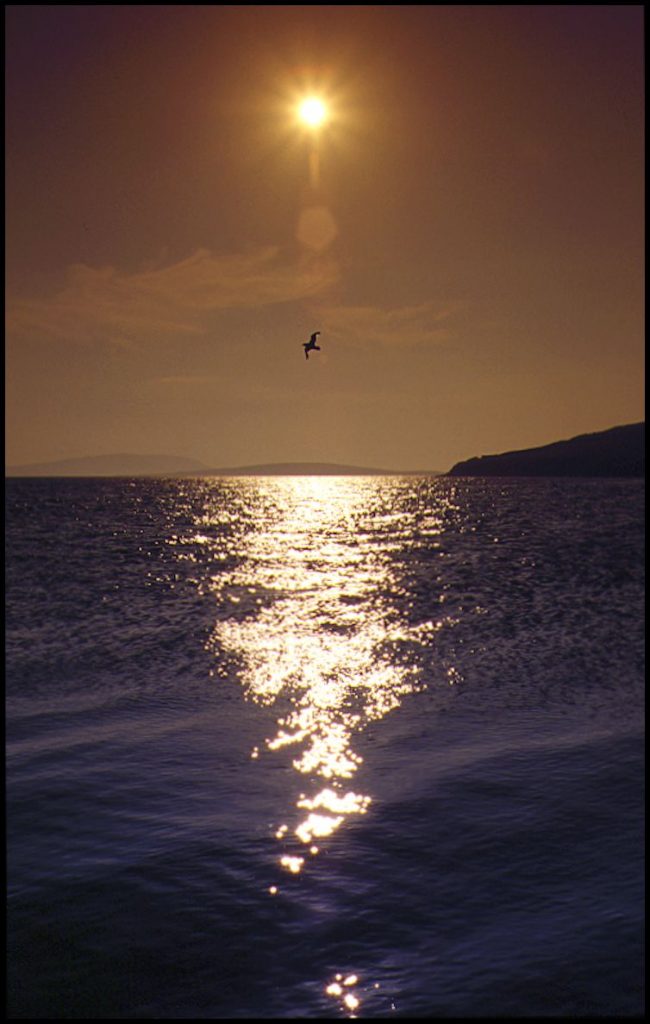

The view of the Westside and Eynhallow from along this part of the road is most beautiful. It is a view that has lingered in the minds of several Scandinavian authors, especially those who have been fortunate enough to see the sun setting behind Eynhallow and the evening-glow warm the Saga-sites on either side of the Sound between the Island and the Mainland.

WESTNESS HOUSE

Just visible amongst the trees below the road on the left is Westness House and gardens. For several generations this was the home of the Traill family, who also owned Woodwick House, the large house you will see to the North West of Tingwall jetty on your return to the Mainland. Dr. Traill planted the trees and gardens of Westness which were thought to be the most beautiful of their kind in Orkney right up to the beginning of this century. Certainly the positioning of both Westness House and Westness Farm (the farm next to the house) have no parallel for charm in the Northern Isles. The story of Westness House has yet to be written, but when it is the eighteenth century John Traill will no doubt be one of the central figures. When suspected of supporting Bonnie Prince Charlie he is purported to have taken refuge, along with others, in the “Gentleman’s Ha” on Westray. It is said that his home was burnt down and presumably the present Westness House is basically his rebuilt home.

The house and gardens are open to the public, viewing by appointment only. (see General Information page). At the bottom of the garden is a small private chapel which seats nine people and is still used by the Episcopalians who live on the Island. This chapel was built at a much later date.

Having reached the bridge, Westness Cottage is on the right and to the right of the cottage is a track climbing up into the hills, keeping to the side of the geo or valley through which the Westness burn cascades. The track leads to Rousay’s two largest lochs; the Muckle Water and the Peerie Water, i.e. the large and the small lochs. The Frotoft folk cut their peats up there to this day. However, to visit the lochs and return would take over an hour and a half.

We recommend that the walk should continue, not along the road, but down the track on the left just over the bridge down to Westness Farm. Pass through the farm and continue the walk along the shore, making sure to close all gates behind you. In the field between the burn and Westness House are a number of smaller cairns and nearer the farm is the disused threshing Mill with its large overshot wheel.

Westness Farm is one of the largest farms in the Northern Isles and as we have mentioned was cleared and “improved” by George Traill in the 1840’s. For as far as we can now see on Rousay and as far again there are no occupied crofts.

SHORE WALK

A walk along the shore brings us to an outstanding Norse site, still being excavated (1978) by Curator Sigrid Kaland from the Historical Museum, Bergen, Norway. It will eventually be laid out as yet another ancient monument – the first Norse one in Rousay and completing the time-scale from prehistoric times to the present on this South Western shore.

The “Noust” or boathouse is the first part of the settlement we come to on Moa Ness. It is remarkable that this site was not discovered until the 1960’s when one considers that after leaving Saviskaill Bay and sailing round the North Western coast, this is the first place one could pull up a boat, even at low tide. We can see clearly that the flagstones on the shore are naturally split and that there is a sandy inlet. The noust is sheltered from the strong currents of the Eynhallow Sound. The building has, presumably, been an open construction measuring 10 x 5 metres with low walls which were primarily a protection against strong winds.

Approximately 50 metres West of the noust on the highest ground of the Ness or headland lies the Norse cemetery. None of the graves can be seen on the surface and their exact numbers are not yet known, but four have been uncovered and there are certainly several more. The cemetery was accidentally discovered in 1963 when the farmer was digging a hole to bury a dead cow and by chance uncovered a richly equipped young woman’s grave. The famous Westness brooch now in a corner of the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh, was one of three brooches found in the grave. Two were 9th. century and the Westness brooch itself is not later than the middle of the 8th. century, and was already an heirloom when buried. There were several other grave finds including a necklace of 40 beads and toilet equipment. From other skeleton material found it appears that this young woman died in childbirth. It is one of the best equipped graves ever found in the Atlantic Islands. A mere four metres away was revealed yet another outstanding grave with the remains of two skeletons.

The uppermost body in this oval 9th. century grave had been a woman in her sixties, and under both this skeleton and a layer of sand lay a 30 year old man. His head had rested on his shield and at his side were gaming pieces, arrows, sickle, knife, scissors and some toilet accessories. It is believed that the older man may have been a human offering at the burial. The 10th. century Arab ambassador, Ibn Fadlan, describing a Viking burial, wrote:- “When a Chieftain among them has died, his family demands of his slave woman and servants, ‘Which of you wishes to die with him’, then one of them says ‘I do’ “.

Just over 300 metres farther West lies the farmhouse and associated buildings. There are at least four buildings lying North South. The main house has two long halls with fireplaces and other smaller rooms, whilst on the Eastern side of a paved gangway are presumably a byre for cattle and sheep. There are several building phases and more buildings yet to be uncovered all round the settlement. Seeds found tell us that amongst the plants grown were flax, barley and oats. One problem here is the dating of the site and the great temptation to associate it with the Sigurd of Westness who features in the Orkneyinga Saga. The graves suggest that the settlement could easily be from the earliest Viking colonisation of Orkney while Sigurd lived in the 12th. century. Before briefly describing the Saga events that took place on the Westside we can notice the adjacent turf-covered mound known as the Knowe of Swandro. It is wrongly identified in the Inventory of Ancient Monuments for Orkney as a Viking grave, whereas it is, quite clearly, another Broch. This may have been a good quarry from which the Norsemen could carry building materials for that farm.

Although Sigurd of Westness is the only Rousay man to feature in the Saga his position is an important one as a close friend of Earl Paul Hakonsson. As usual the Saga events are complicated with rival claimants to the Earldom plotting against each other with their respective supporters. In 1137 Earl Paul, son of Hakon who had slain Magnus on Egilsay in 1117, was visiting Sigurd at Westness, probably to seek his advice on the approval of the rival claimant Rognvald (the builder of the St. Magnus Cathedral). Before Rognvald and Paul could meet there was a very unexpected turn of events. Early one morning Earl Paul was out with some friends otter hunting when suddenly that Norse opportunist Swein Asleifson of Gairsay appeared with his men and attacked the hunters. (Swein had previously been out-lawed by Earl Paul). In the attack all were killed except Paul and he was kidnapped, never to appear in Orkney again. Sigurd and his two sons never swore allegiance to the new Earl Rognvald but waited in vain for Paul to return. It was after this successful return to Orkney from Norway that Rognvald began to build St. Magnus Cathedral.

Where did Sigurd live? One thing seems certain that the Chieftain’s “bu” or manorial farm was not at the present day Westness farm. There is no “ness” or headland there, unless the name describes the whole of this part of the Island. The obvious topographical “nesses” are those of Moaness and the one near Swandro. It is here we find the Norse settlement “noust” and cemetery, but on the other hand such an important 12th. century Chieftain as Sigurd would likely have lived in something more elaborate than this farm. We remember also that the Chieftains appear to have had private chapels, some of which later became the parish churches and this leads us to the strong rival claimant for the site of Sigurd’s “bu” a few hundred yards further along the shore. At the risk of discontinuity we can take up the story when we reach the site. We have dwelt on the excavations and Sigurd, but as nothing is mentioned in the Orkney Ancient Monuments Guide more comment was necessary than for the frequently described cairns.

KELP PITS

If we follow the shore line just a little west of the Knowe of Swandro we can see all that is left of a once important source of income for the landowners, i.e. kelp-burning. The ashes of kelp (seaweed) were used in the southern glassmaking industries and from the first half of the eighteenth century until towards the middle of the nineteenth century large quantities were shipped from Orkney. The industrial archaeological remains we see are the round shallow saucer-shaped stone-filled pits, a few feet wide, in which the kelp was burned. While the women earned from the spinning of flax or the plaiting of straw, the men’s summer work was partly the processing of kelp.

After locating the kelp pits we now walk towards the ruined houses and the church we can see. Nearer the shore are more partly explored cairns and on the right we look up at the Ward Hill. There was such a hill on almost every Island and the name is derived from the Old Norse “Vardi” = beacon. The local Norse Chieftain was responsible for maintaining and lighting his warning beacon at the enemy’s approach.

If it is low tide you may see seals lying on the outer rocks below the ruined buildings. If they are not there then you may hear them ‘singing’ from the skerries between Rousay and Eynhallow.

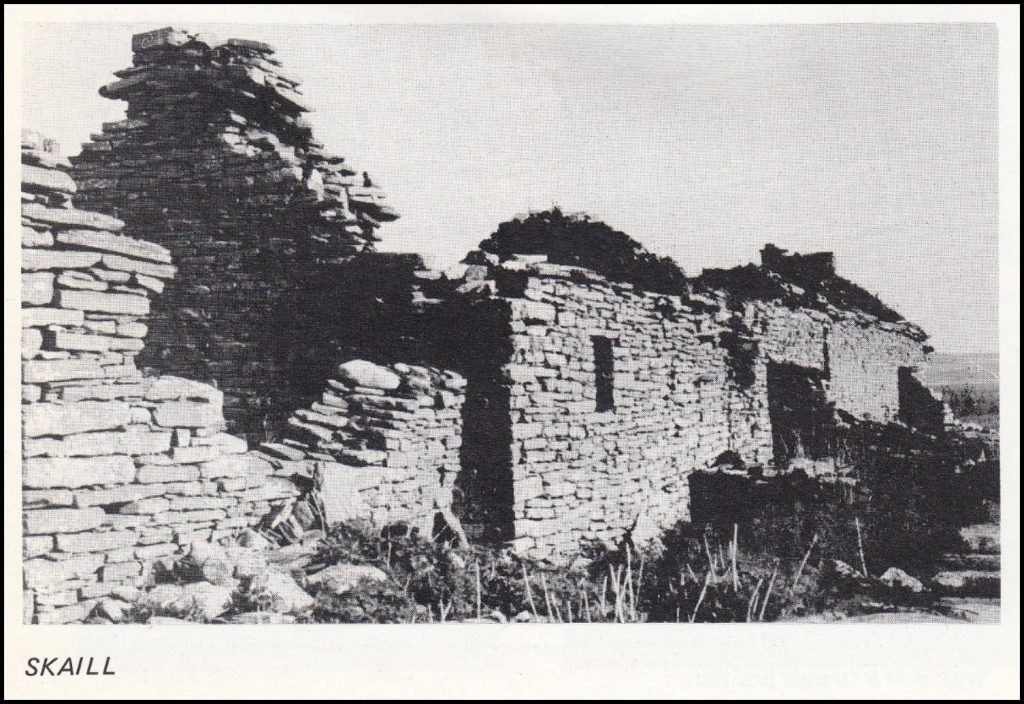

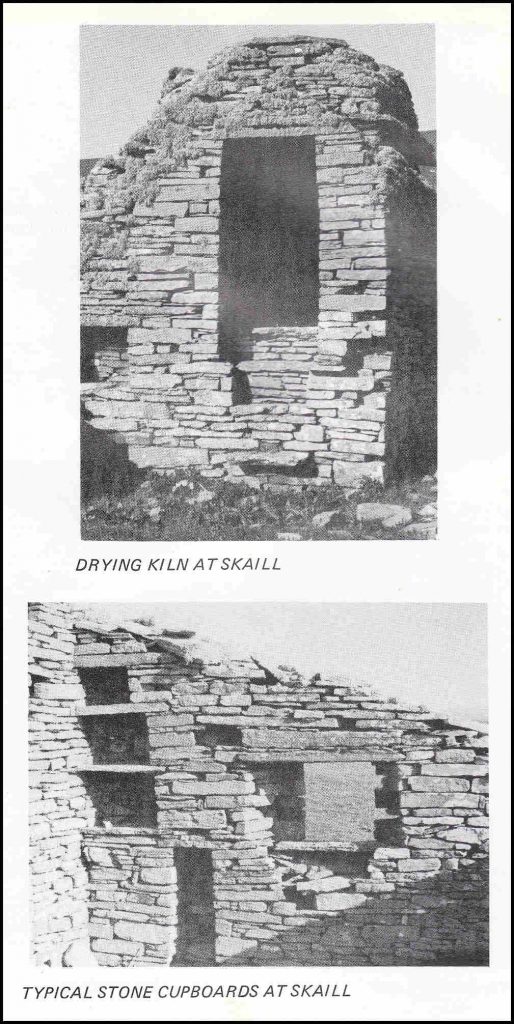

The first deserted farm we come to is Skaill. The tenants were evicted in the last century. The name Skaill is derived from Old Norse “Skali” meaning hall, and it is usually associated with a more important Norse settlement. Most historians believe this site to be the home of Sigurd of Westness. The Skaill estate later became Bishopric property. The actual building is immediately north of the Church. Before moving over to the Church take a look at the well-preserved round drying kiln, in which the corn was dried, at the end of the barn. This is a typical feature of old Orkney crofts.

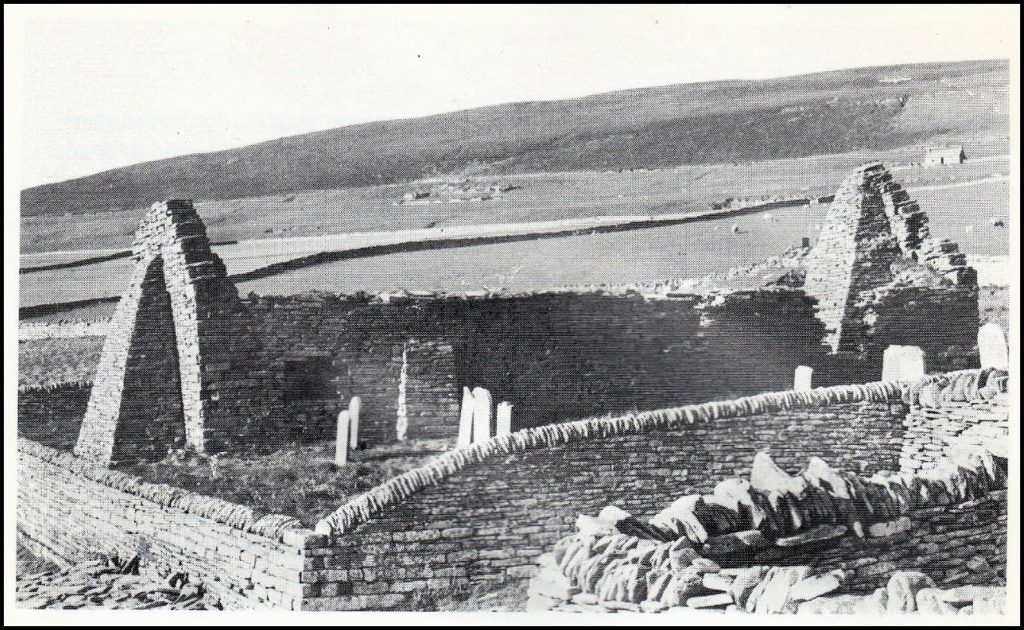

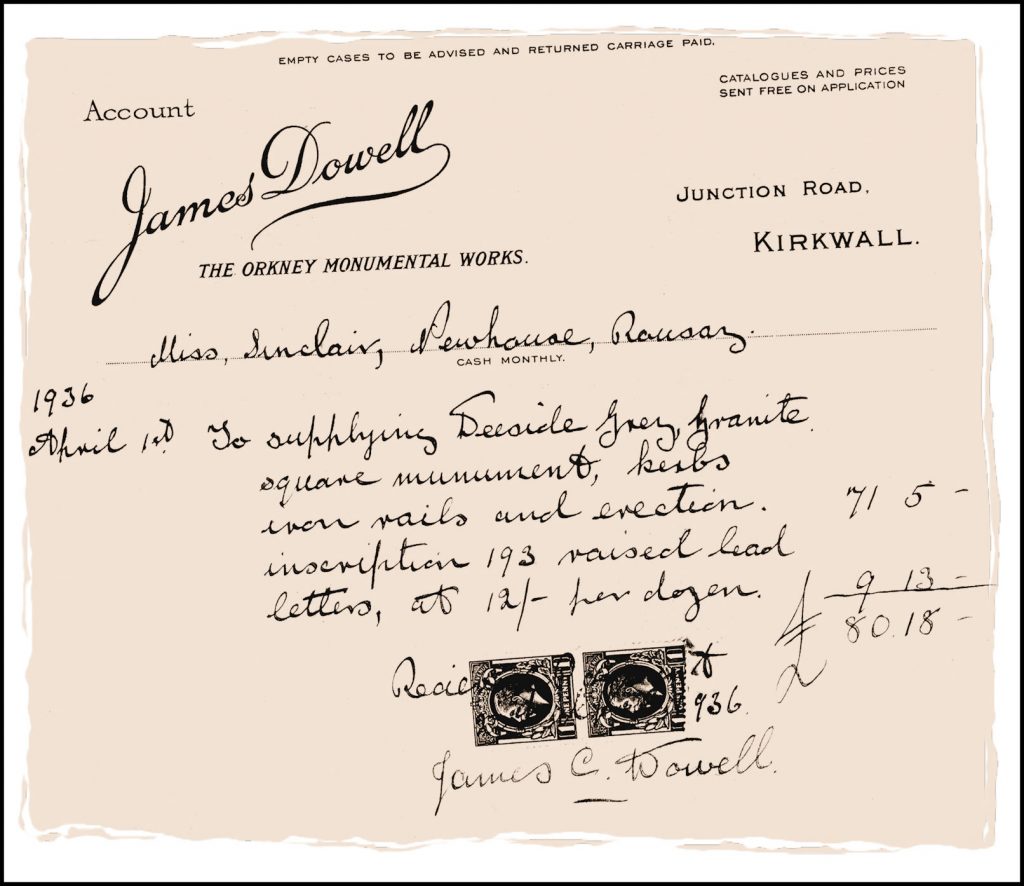

The old Church of Skaill was dedicated to St. Mary but is more commonly called Swandro or Swendro and the name presumably deriving from the personal name “Swein”. It is a single chambered rectangular building 53 ft. by 14 ft. The Norwegian archaeologist Dietrichson and architect Meyer, at the beginning of this century pointed to similarities between Swendro Church and the Magnus Church in Egilsay, and they were in no doubt as to its early medieval origins. However, the inventory of Ancient Monuments published some 30 years ago says that the building is post Reformation. Two panels of Scots pine now in the National Museum, Edinburgh, were originally here, one dated 1622, the other 1798. The church was in use until the clearances and the churchyard, which is in need of repair, was used as late as the 1920’s.

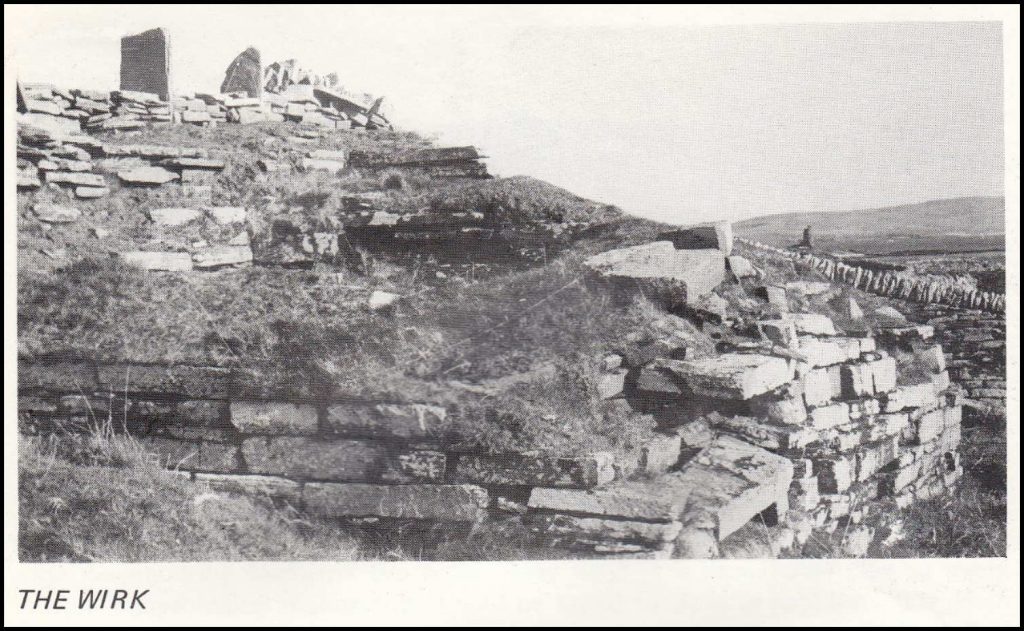

As we have mentioned there are the ruins of a building immediately outside the north churchyard wall which is generally believed to have been Sigurd’s home. It is known as the Wirk from the Old Norse “Virki” (fortification) The remains are of a small tower with thick walls enclosing a room 10 ft. square. From the eastern side of the tower a wider rectangular construction is continued some 86 ft. farther East. It is a well constructed building with its stones laid in lime which contrasts greatly with the adjoining dry stone walling.

We would benefit greatly from a re-excavation of the site. The authors of the “Inventory” compare the walling of the structure with the twelfth century Cubbee Roo’s Castle on Wyre. There are probably few other Orcadian structures that are such a mystery. A “Fortalice” is mentioned in a 1556 Charter pertaining to lands of Brough (the next farm ruin) but there is no clue as to where or what the “Fort” was. It has to be admitted that as a fortress, even to be used only occasionally, the Wirk is in a strange position.

BROUGH

However, we continue our walk towards the next building which was the important house called Brough. Dr. Marwick pointed out that there is a well, known as Mary Well, at the edge of the shore between Skaill and Brough. Although there is no tradition preserved, he believed it may have been a Holy Well. Today it is difficult to see.

Dr. Marwick wrote of Brough in 1948:- “Ruinous and deserted as it now is, Brough was in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries one of the most important houses in Orkney – no fewer than three Craigies of Brough having been Lawmen of Orkney”. The farm lay in Outer Westness and some evidence indicates that part of the Westness estate was private Earldom property which probably came into the Craigie family through James Craigie’s marriage to a daughter of Earl Henry St. Clair in the fourteenth century. The property was one of the most valuable Odal estates in the whole of Orkney. The previously mentioned Charter of 1556 was the sale of Brough by Magnus Craigie to his kinsman Magnus Halcro who was Cantor of the Cathedral. This ambitious and able opportunist married in 1563 the daughter and heir to Sir James Sinclair, the victor at the Battle of Summerdale in 1529. This was the last battle in Orkney. After Halcro’s death the property was acquired, illegally by all accounts, by Earl Robert Stewart. He evicted the Halcro heirs. Robert Stewart was the son of James V of Scotland and thereby half brother to Mary Queen of Scots. He had been created Earl of Orkney in 1581. It was he who built the Earls Palace at Birsay. However it came into the Halcro family again in 1593 and there it remained until the Traills took it over.

How sad it is that this once important farm is now but a ruin on a sheeprun. Between this building and the sea are the remains of a broch — the South howe of the three brochs in this area. It has not been excavated and every year that passes, more disappears into the sea.

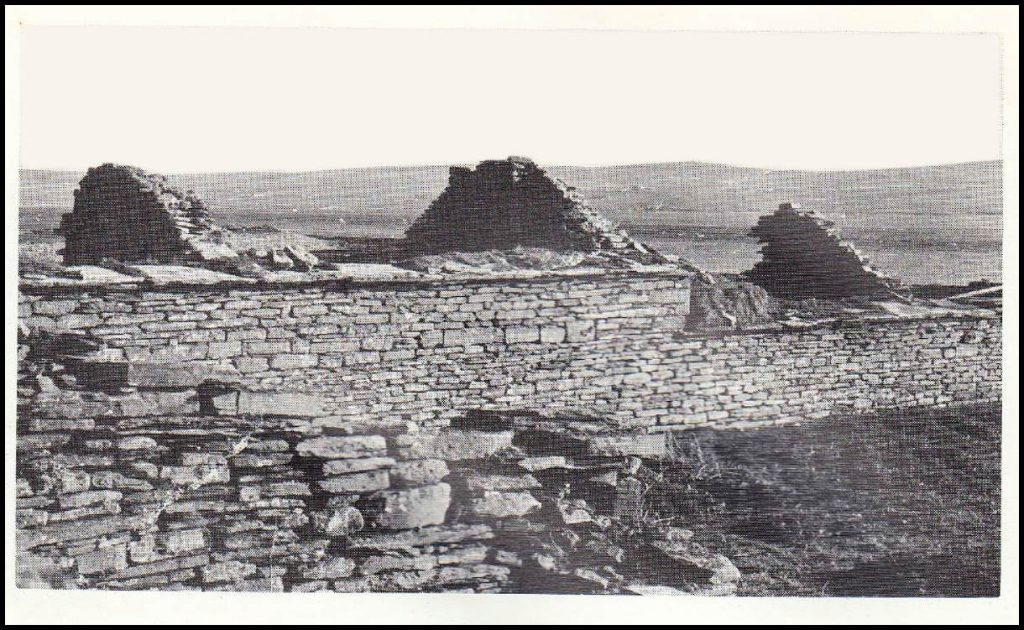

MIDHOWE CAIRN

By now we are curious to see inside the hangar-like structure some yards further along the coast. This is the famous Midhowe Stalled Cairn, described in the Guide to the Ancient Monuments of Orkney. The building we see was erected to protect the tomb underneath after it had been excavated at the expense of Mr. W. G. Grant in the 1930’s. This megalithic chambered tomb from the third millennium BC is called a “Stalled” cairn because it is divided into twelve compartments by upright slabs projecting from the side walls just as the stalls of a byre. The barrow is exceptionally large, the external measurements 106 ft. long arid 42½ ft. wide. The chamber is 76 ft. long and 7 ft. wide. Lying on stone benches between the stalls were found the remains of 25 human skeletons. Otherwise the finds were few but included some pottery and a few animal bones: ox, sheep and Orkney vole.

For a more complete description and plan of Midhowe Cairn see the Department of Environment Guide. The guide also contains a good description and plan of the neighbouring Midhowe Broch. In many ways it is remarkable that so many major archaeological monuments should be found so close to each other but when we think about it nothing is more natural than a continuity of settlement in an area of good arable land with the sea at hand.

MIDHOWE BROCH

Midhowe Broch is, as the name tells us, the middle “haugr” or mound of three. The North Howe is the large mound 100 yards from the shore and 300 yards from Midhowe. Only Midhowe of the Rousay Brochs has been excavated and once again we are indebted to Grant of Trumland House for his efforts in the 1930’s. Nearly all brochs are to be found in the north of Scotland and there are great concentrations of them in Orkney and Shetland, roughly 100 in each Island group. They are generally considered to have been tower-like structures, as the best preserved example, Mousa Broch, Shetland shows, but most are now grass covered mounds like those we have already passed. After confidently dating them to the Iron Age from finds like Roman Pottery, coins, saddle and rotary querns we are then left to speculate who built them and why. Their sophistication and defensive positions speak for themselves and Midhowe is a superb example of both. With a spring inside and access to the food from the sea the Broch dwellers must have felt quite safe. Their builders may have been the indigenous farming population threatened by the invaders from the South; the culprits being either the Romans themselves, the tribes displaced by the Romans, or, the Brochs may have been built by an invading people. Their distribution corresponds approximately to the lands known to have been occupied by the Picts, but even here we are skating on relatively thin ice because the “Picts” are a thorny subject only now being archaeologically investigated. Whoever the Broch dwellers were their need of a defensive structure became less and the inner ditch was built up with secondary houses, one of which at Midhowe has an iron smelting hearth. Like the Cairn builders the Broch dwellers were farmers, and finds of spindle whorls and pieces of combs indicate that they knew how to both spin and weave cloth.

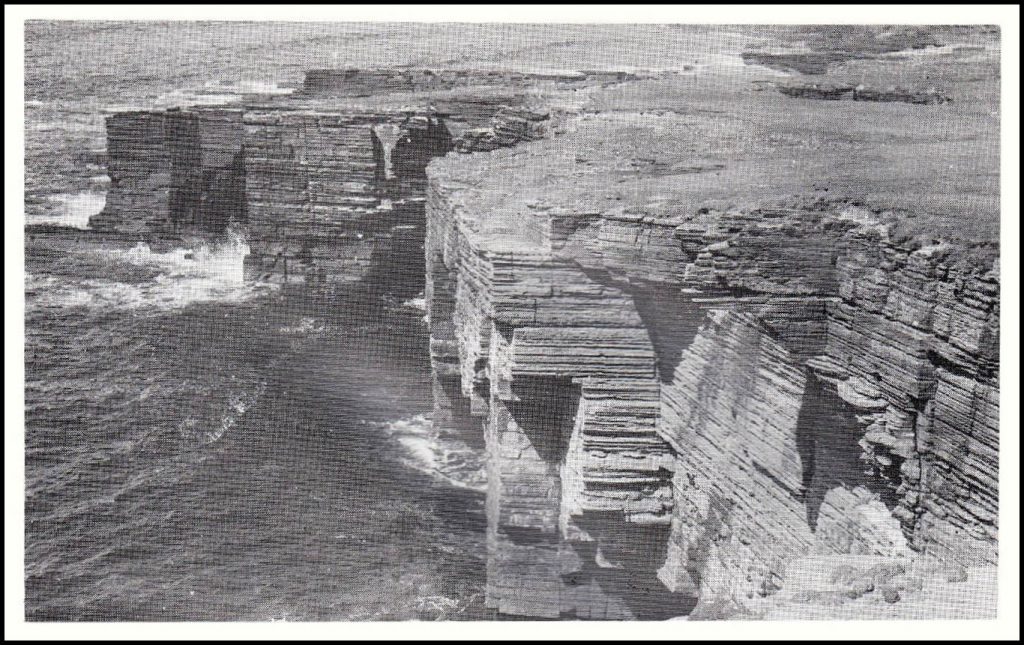

SCABRA HEAD

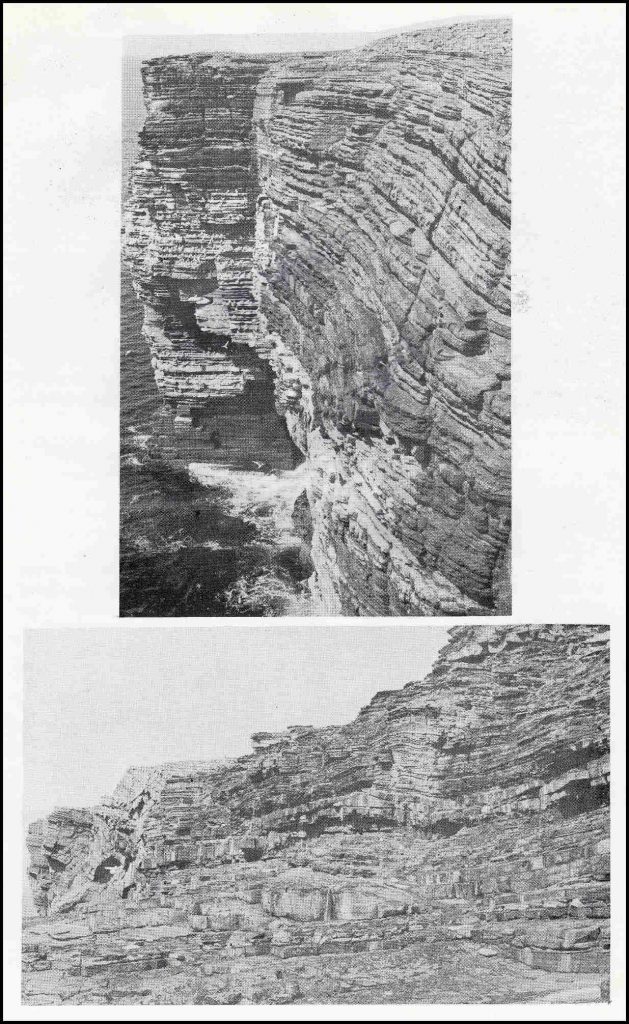

Our Rousay Heritage Walk is nearly at its end and there is just one more historic site to be seen (maybe only at a distance if time is short). We should first continue our walk to Scabra Head, some 300 yards from the North Howe. From the Brochs to the headland with its caves we can admire the scenery which we have perhaps neglected a little in the brochure. Here the land rises and we encounter the first of the Rousay cliffs which are particularly fine on the North West of the Island, at the Lobust and Helliaspur. The name Scabra Head or Skarbrae Head is derived from Old Norse “Skjald-breidr” (broad like a shield). Please keep an eye on children and animals here as the cliffs crumble easily and walking too near the edge is dangerous. The headland is an ideal place for bird watching or just generally resting your feet and listening to the waves beat on the inside of the caves below.

In order to see our last site we must wander up and over the headland, making sure we do not tread on fulmar’s eggs. To the East we have a good view of the Rousay Terraces from the Ward Hill down to the sea. To the West we are now looking over the broad valley of Quandale, with the interesting blow holes called the Sinians of Cutclaws down on the left near the shore. The large number of burial mounds in this area speak of quite a dense population which continued to be so until the evictions in 1840, already described. We have already passed some of the new homes of the luckier tenants re-housed in Frotoft.

QUANDALE

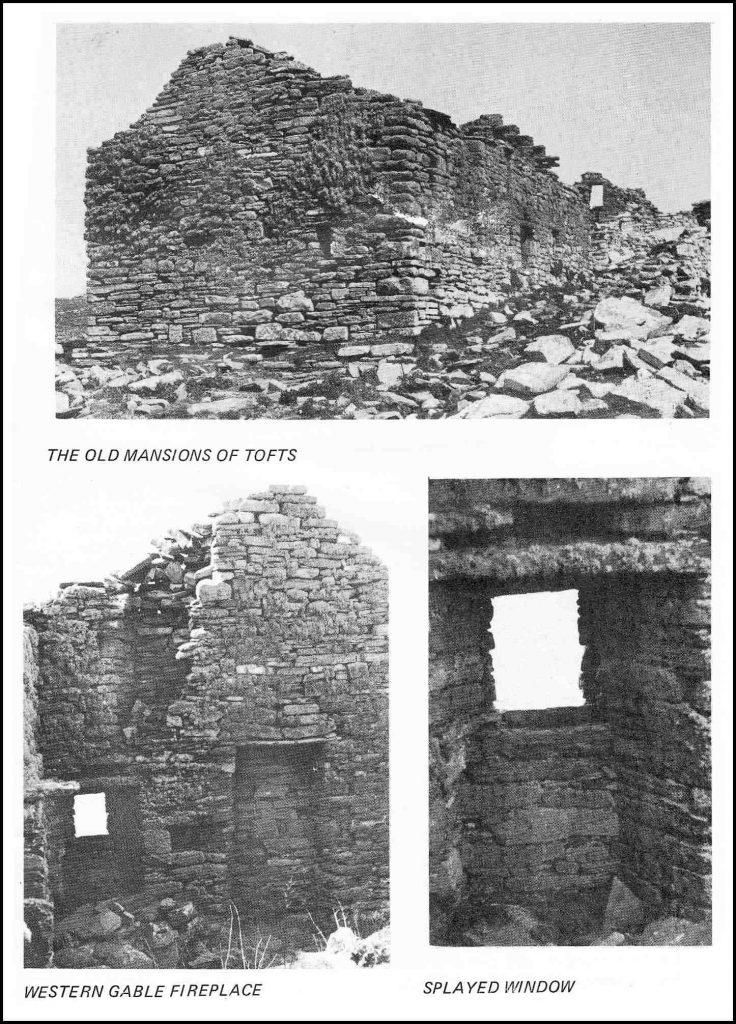

On the Northern side of Quandale the sites of old crofts are still visible with their greener arable rigs close to the piles of stones. There is one croft which stands out though, and this is certainly no anti-climax even after the imposing Midhowe Monuments, for here we are faced with the old mansions of Tofts. The Orkney Historian J. Storer Clouston believed this to be the oldest two storeyed house in Orkney and in 1923 hoped “that this unique homestead will not be allowed to fall into further ruin, if any means, or any money, can be found to avert such a fate”. Unfortunately nothing has been done and this ancient house is slowly falling down.

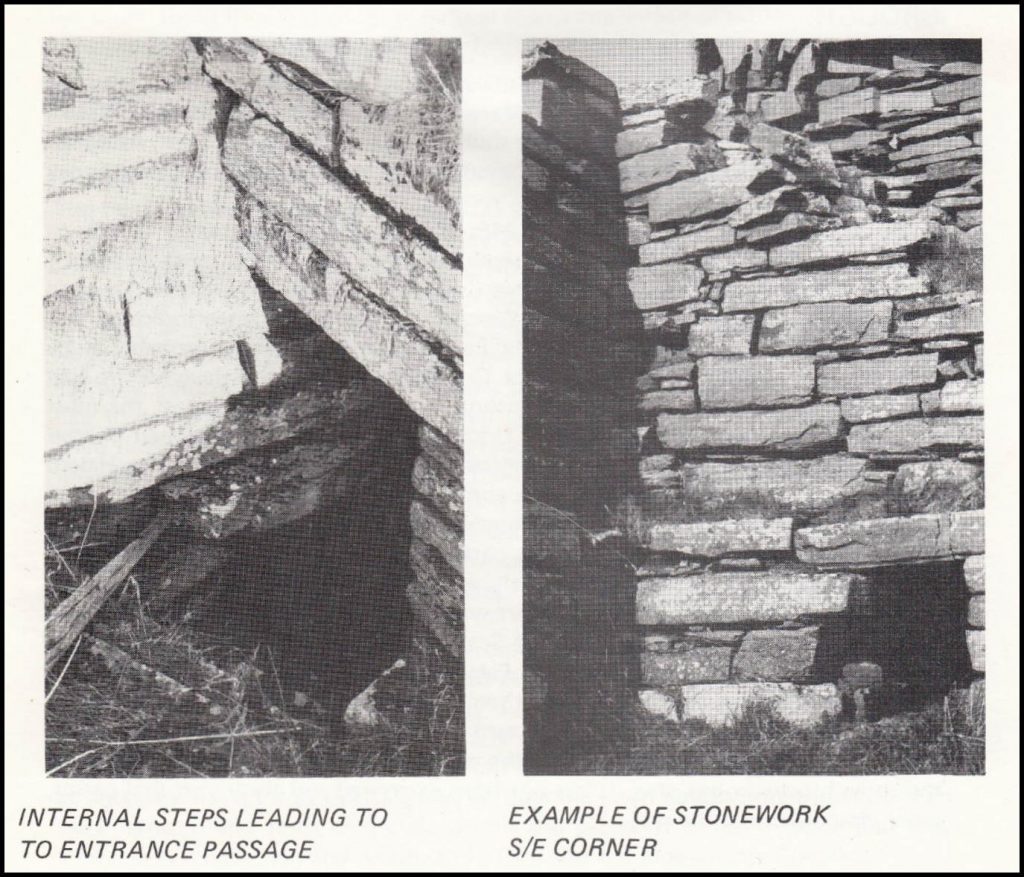

The buildings deserve study because although small, the house itself has one or two unusual features. The whole is divided centrally by a 3 ft. wide passage with a door at each end. In the Southern wall there is a small window at each side of the door with even smaller windows above. All the walling is drystone and very well built. The staircase to the first floor was inside the Eastern room and ran along the North wall, not across the passage wall as one would have expected, so enabling anyone ascending to enter the upper rooms at their highest. The slightly splayed windows have had window frames and each has an inset window seat. There is a fireplace in the Western gable downstairs and this is a remarkable feature when we know that nearly all the houses in Rousay in the 1840’s were said to have open hearths in the centre of the room. The downstairs rooms were low, they had just over 6 ft. headroom. Storer Clouston analysed these features and believed that this was some “gentleman’s” home not later than the early 17th. century. He asked – “but what gentleman indulged in stone window seats and yet was content with rooms 12 ft. square and barely 6 ft. high, and with only one single fireplace in the whole building?”. He agreed that the building had several features which resembled early keeps and he was convinced that the house was built as a semi-defensive structure. The problem is when? All the evidence, both historical and architectural, points towards the early fifteenth century. In this period, Orkney was subject to constant fierce attacks by what can only be described as pirates from Western Scotland.

It is probable that a defensive structure would have been built at this time and we imagine Tofts in its present form to have been built then. Storer Clouston concludes that from 1570 to 1700 there was nobody of any local importance who was styled “of Tofts” or “in Tofts” which suggests that its day of glory was before this time. The buildings round the house are the stables and barn, plus two byres. It is a remarkable collection of buildings, inhabited only by birds today.

From Quandale we must wander back up to the road and begin our walk back to Trumland Pier. From the quarry on the bend of the road it takes about two hours to the pier and you would be wise to accept all lifts from passing Rousay folk if you have not arranged any transport to pick you up.

It has been a long walk but Rousay must be one of the few places where we can discover so many different monuments illustrating past ways of life. We hope it has been enjoyable and that these few pages have, in some way, kept your mind from thoughts of aching legs.

ACCESS TO ROUSAY

Rousay is easily accessible from Tingwall (MR. 402228 0.S. Sheet 6) in Evie on the Mainland of Orkney. There is a bus service from Kirkwall bus station on a Monday, Friday and Saturday, leaving at 9 am. and returning at 4.30 pm in the evening (subject to alteration on school days). This service meets the Rousay boat. At other times a taxi can be hired from any of the operators on the Mainland. J. A. Rosie, The Shieling, Evie (Evie 227) is prepared to run a mini-bus for larger parties

If you bring your own car, turn off the Kirkwall to Stromness road at Finstown and take the A966. After six miles a sign to Tingwall Jetty indicates a turn down to the sea. There is a free parking and a shelter with a phone.

BOAT SERVICE

Mr Magnus Flaws of Helziegetha, Wyre (Rousay 203), runs the boat service to Rousay, Egilsay and Wyre. The boat leaves Tingwall at 10.l5 am and 4.30 pm For a service outside these times, please check with the boatman.

TRANSPORT ON ROUSAY

Scheduled Bus Service – from the pier (meeting boat) to Midhowe Broch. Mon. Sat. at 10.45 am. (June, July, & August). Other times by arrangement.

Self-Drive Cars – Louise Owen, Taversoe Hotel. (Rousay 325).

Taxis and Self-Drive Cars – telephone Chris and Mary Soames, Brendale, Rousay. (Rousay 234). Also mini-bus hire, day tours arranged for parties to suit the unique requirements of each group. A Guide can be arranged if necessary.

Taxis – John Mainland, 4 Frotoft, Rousay (Rousay 270).

Bicycle Hire – Tommy Gibson, Brinola, Rousay. (Rousay 261). Just above the pier.

Pony & Trap – see Quoys Stables & Saddlery

ACCOMMODATION & SERVICES

Taversoe Hotel – licensed family hotel. Bed & Breakfast. Full Board. Bar Meals. Sandwiches & Coffee. Activities offered include Shooting, Trout Fishing, Sea Angling, and Diving. Near to all ancient monuments, ideal centre for ornithologists. lvan & Louise Owen, Taversoe Hotel, Rousay (Rousay 325).

Old Mlll Cottage – on a working farm, sleeps six, close to pier and sea. Farm produce available, fishing and shooting by arrangement. Jeremy Hulme, Trumland Farm, Rousay (Rousay 279)

OTHER SERVICES & ACTIVITIES

Quoys Stables & Saddlery – Hire a pony and trap for a leisurely island tour. Also riding lessons and pony trekking for beginners or experienced riders – all tack provided. Glyn & Carol Chrystal, Quoys, Rousay. (Rousay 330)

The Orkney Pottery – A Craft Pottery halfway between Rousay pier and Midhowe Broch producing a select range of handthrown Stoneware and PorceIain fired to a high temperature. A range of work is always on display in the showroom, where coffee and scones are available. Frank Harris, Banks, Rousay. (Rousay 266).

Hullion Shop – A general island store selling all manner of goods and petrol. David Gibson, Hullion, Rousay. (Rousay 264).

Pier Shop – A small general merchant – mainly for groceries. Dorothy Munro, Pier Shop, Rousay. (Rousay 391).

Rousay Processors – An island-owned shellfish processing factory. In season, Lobster, crab and scallop can be purchased at the door. Rousay Processors, The Pier, Rousay. (Rousay 216).

The island has a resident doctor and nurse.