FROM ROUSAY, TO VERNON, BC

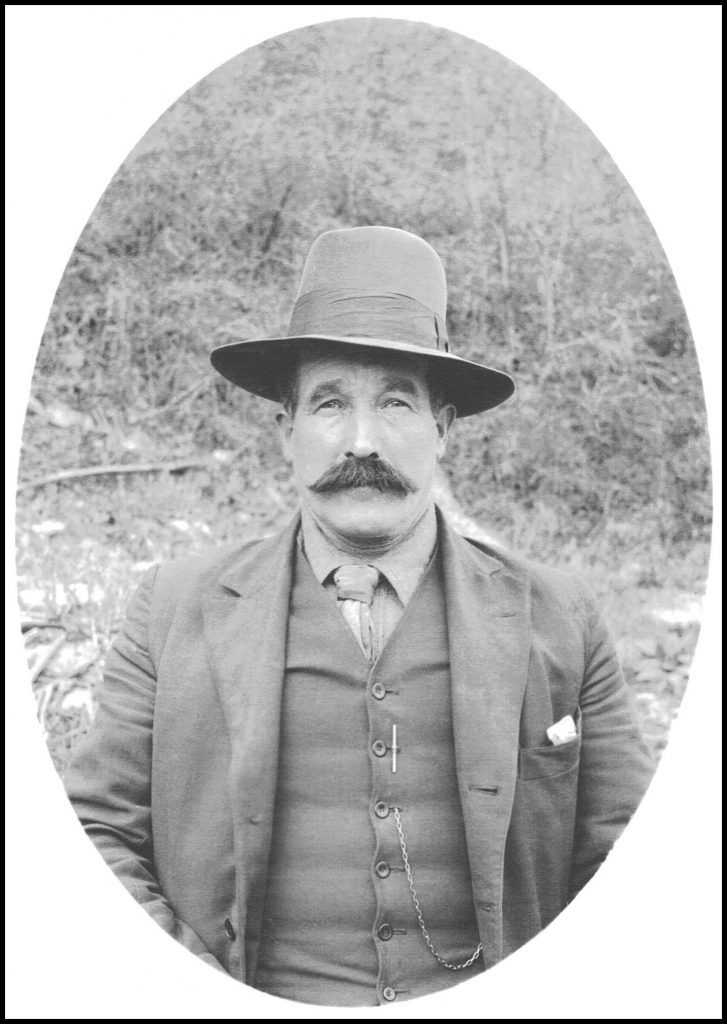

This is the life story of Rousay man William “Billy” Inkster. He was born at Quoys, Sourin, on October 11th 1866 – and died on February 13th 1940 in Okanagan Landing, British Columbia, Canada.

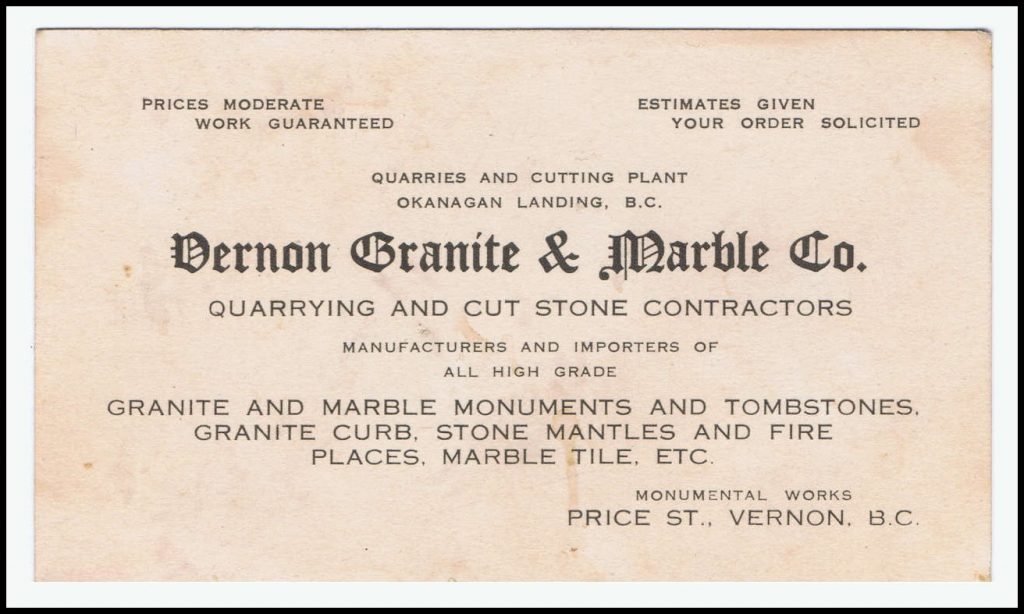

The first article is his obituary, which appeared in The Orcadian in April 1940. The second tells of Billy’s emigration to Canada and his involvement with Glasgow-born John Russell in the Vernon Granite and Marble Company. The article, written in 1977, is reproduced with the permission John Russell’s grand-daughter and great grand-daughter, who were also kind in supplying all the images and their captions.

FREESTONE CUTTER WHO GOT ON

ROUSAY MAN’S DEATH IN BRITISH COLUMBIA

Announcement of the death of Mr William Inkster, 0kanagan Lake, British Columbia, has brought to light the history of an enterprising Rousay family, who have done well in lands across the sea.

Mr. Inkster’s death was intimated in The Orcadian on March 28th. There are two nephews of the deceased in Rousay, namely Messrs. John and James Sabiston, late of Gripps in the Sourin district.

Mr. James Sabiston (whose mother was a sister of the late Mr. William Inkster) has in his possession a family Bible which dates back to 1836 and it contains full particulars of the Inkster family who resided at Quoys, in Sourin.

William Inkster served his apprenticeship as a freestone cutter in Kirkwall (firm unknown), after which he emigrated to California. After a short stay in California he moved to British Columbia, where, in company with a gentleman named Robert Hannah, the business known as Vernon Granite & Marble Company [quarrying and cut stone contractors, monuments and tombstones] was formed, and which, as far as is known, is still carried on.

Facts from Family Bible. – An up-to-date account of the progress of Mr. Inkster’s business is not known here, as it is many years since any correspondence has been received by his relations in Rousay. As a matter of fact, it was through The Orcadian that the news of Mr. Inkster’s death came to his nephews. As far as is known, the last letter from Mr. Inkster to Rousay dates to the late years of the last war.

The records of the births of the Inkster family is beautifully inscribed in the family Bible (mentioned at the beginning of this article) and is said to have been the work of the teacher in Sourin School at the time. The following particulars of the family may be of interest to readers and relatives at home and abroad.

Father and mother. – James Inkster [Ervadale, later Quoys, Sourin], born 18th March, 1836; Margaret Pearson [of Kirkgate], born 6th March, 1836.

Family. – Margaret Inkster, born 30th October, 1860; Mary Ann Inkster, born 28th December, 1862; James Inkster, born 3rd December, 1864; William Inkster, born 11th October, 1866; Hugh Inkster, born 17th January, 1869; John Inkster, born 13th May, 1873; David Inkster, born 8th May, 1876; Robert Inkster, born 26th November, 1879.

Abillty to go on. – All six sons were tradesmen and went abroad. James Inkster, a blacksmith, emigrated to South Africa. Hugh Inkster (whose widow resides with her sister Mrs. Baikie, Albert Street, Kirkwall) was also a freecutter by trade, and went to Africa. John Inkster, who served his apprenticeship as a grocer with Messrs. Cumming & Spence, Kirkwall, also went to Africa. David Inkster, a blacksmith, served in the Boer War with the Seaforth Highlanders, afterwards went to Hamilton, Canada, where he still resides. The youngest son Robert, a watchmaker and jeweller, still carries on his business in Hamilton, Canada. Margaret Inkster, who died in recent years, was married to the late Mr. John Sabiston of Gripps, Sourin, Rousay. Mary Ann Inkster died in Rousay at an early age.

The fact that the Inkster family were brought up on a small croft (their father being a fisherman) speaks highly of their ability to get on, and also of their parents who, undoubtedly sacrificed much towards the welfare of their family.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

HEWERS OF GRANITE

by David G. Falconer

In the Okanagan Valley, as in many other regions of Canada, the term “building stone” was synonymous with the word “granite” for several decades. Attractive to the eye, and impervious to wear, granite was used for trimming or facing or for totally constructing public buildings, churches, business establishments and private homes. Much of the granite quarrying in the Okanagan Valley has been conducted by one small inter-related family group in the Vernon area.

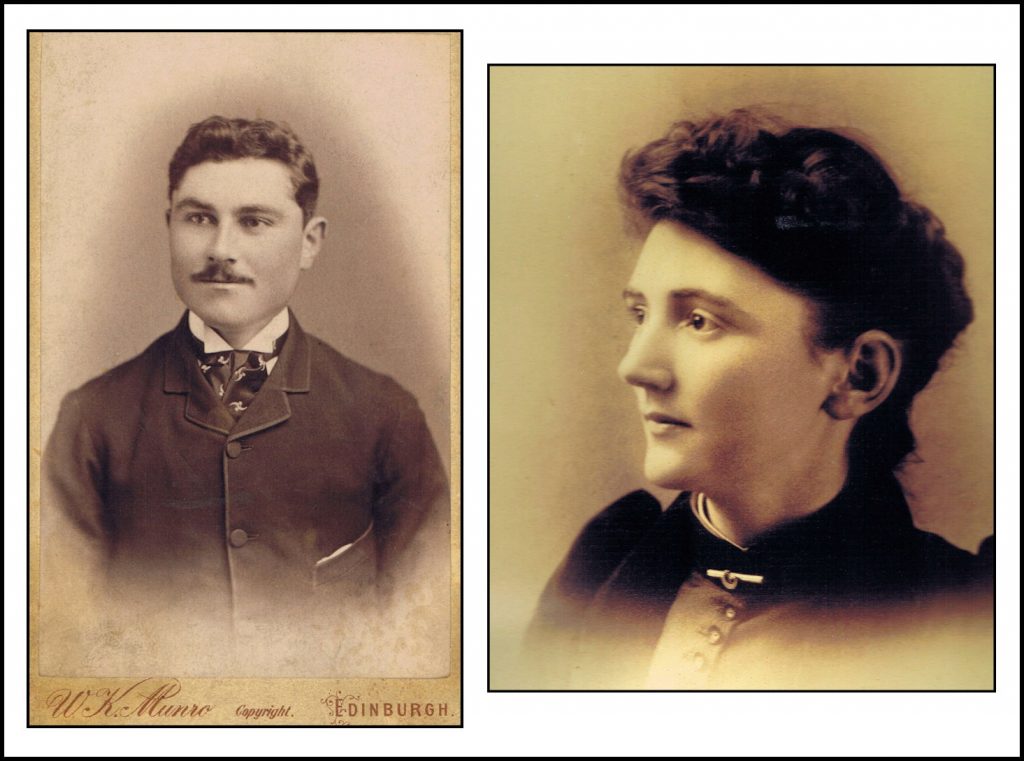

John Russell, originally from Glasgow and Renton-on-the-Clyde, brought his Virginian-born wife, Emma L. Russell, and four children to Vernon in 1902. At that time, their eldest child, Jack, was ten; Jessie (nicknamed Jenny) was five; Hastings was two and Arnold was just one year. Russell was a journeyman stonecutter and a stonemason, with wide experience throughout the western states and Canada in the construction of stone buildings. (He had been Superintendent of the stonecutters on the construction of the British Columbia Parliament Buildings in Victoria.) Mrs. Russell’s health was failing and it was John’s hope that the drier climate of the Okanagan would be beneficial to her.

Shortly after their arrival in Vernon, Russell purchased a building lot at the northeast corner of Pleasant Valley Road and what is now 25th Street. A two-storey frame house (still standing) was built at this location, and became the Russell’s home for several years. The Russell’s two youngest children, Jim and Howard Hays [1] were born in this house.

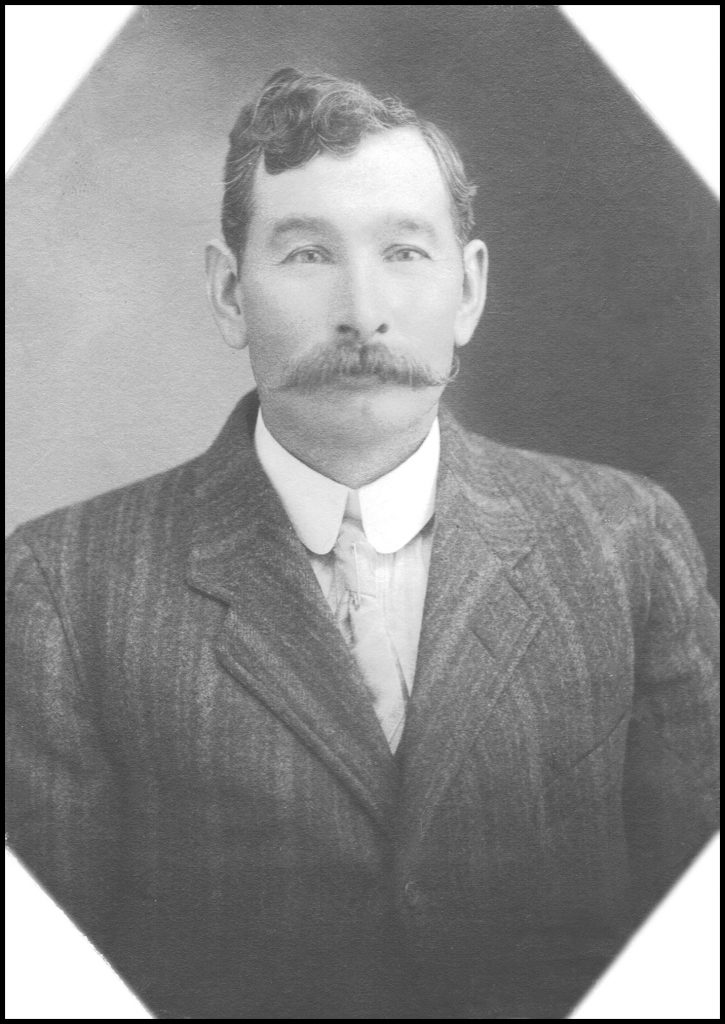

An old friend and fellow-stonecutter arrived in Vernon in 1903. William “Billy” Inkster was an Orkneyman by birth, and came to the Okanagan to seek relief for a respiratory ailment connected with the inhalation of silica dust. Being an experienced carpenter, Inkster assumed a major role in the construction of the Russell home. Following the completion of this building, Inkster decided to renew his involvement with the stone-trade, forming a partnership with two other stonecutters, Jack Hannah and Bob Kemp. “Inkster, Kemp and Hannah” established a stockyard for marble and granite immediately east of the railroad tracks on Barnard Avenue.

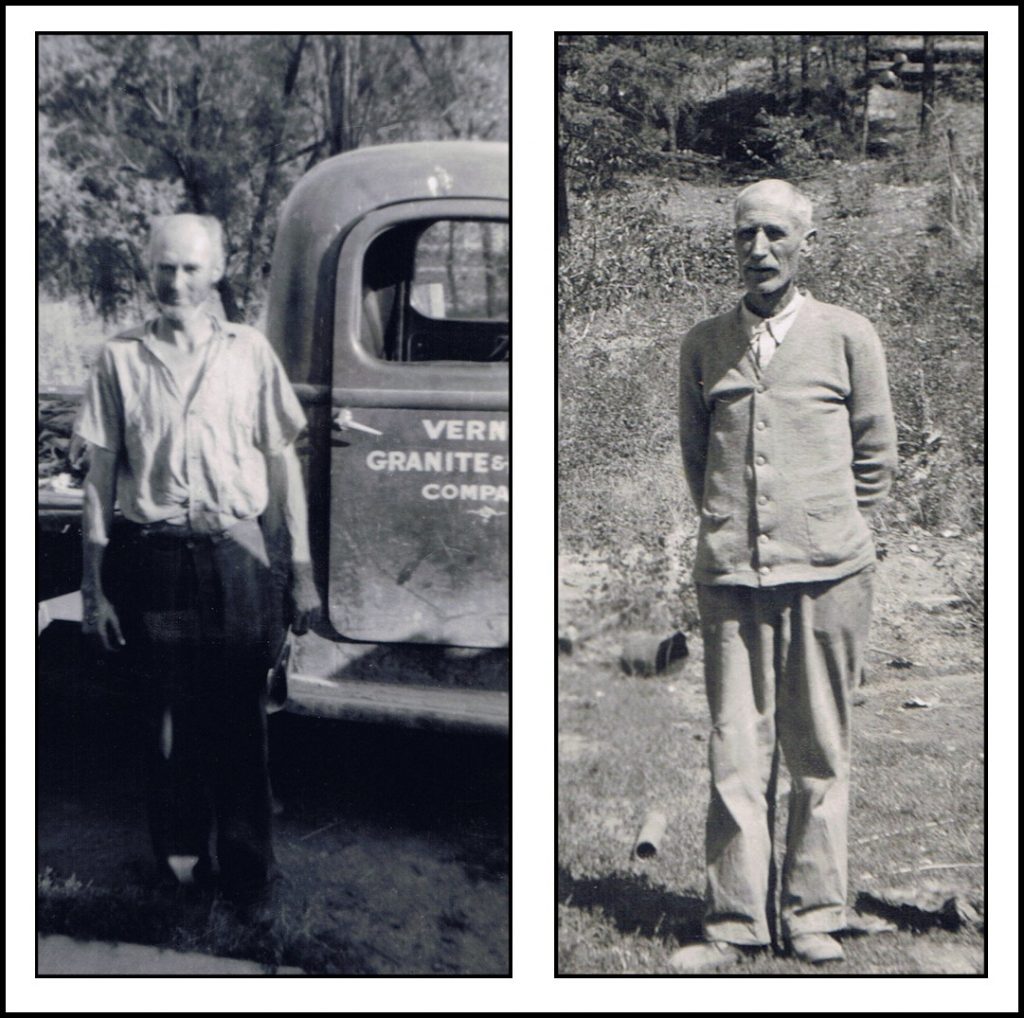

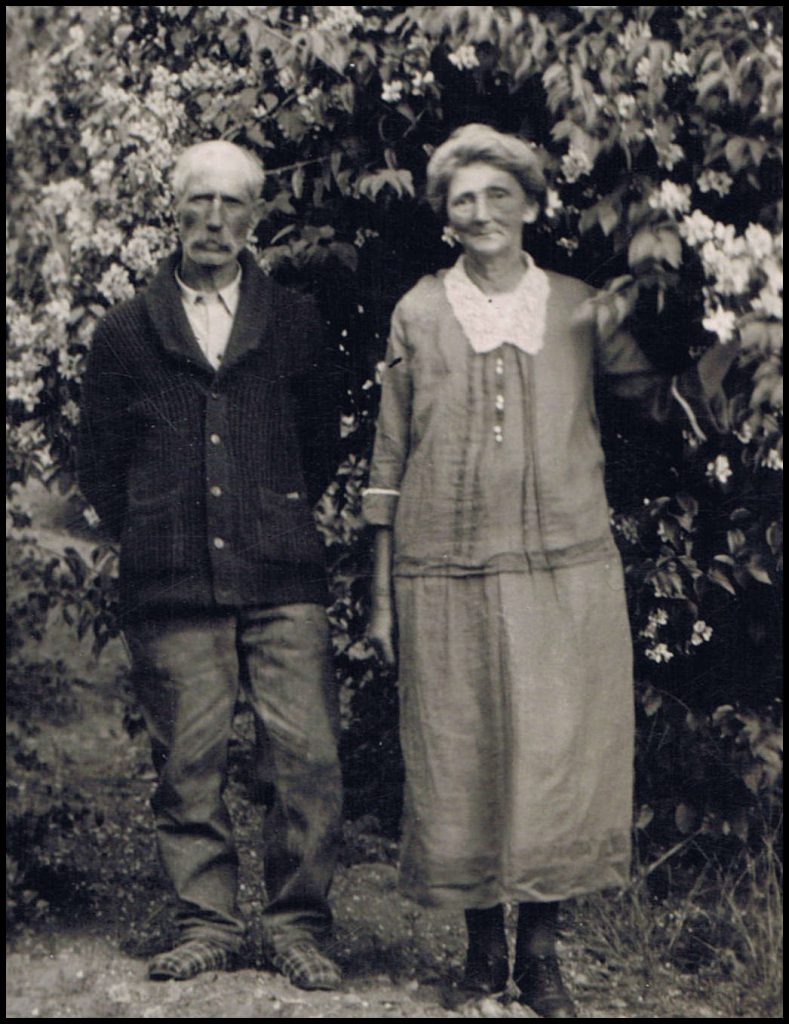

John Russell and Billy Inkster,

pictured at the start of their venture

Their marble supplier was Sam McClay (Vancouver Harbour Commissioner), while their source of granite was a quarry they opened on Okanagan Lake about three miles south of Okanagan Landing [2]. A royalty, based on the cubic footage of stone removed, was paid to the landowner, Benjamin Lefroy, through his business agent, the well-known bird painter, Alan Brooks. Bob Kemp was not with the young company long, as he decided to move on to a better paying job in Sarnia, Ontario. He was bought out by Inkster and Hannah, and the name of the business was changed to “Vernon Granite and Marble Company”. [3]

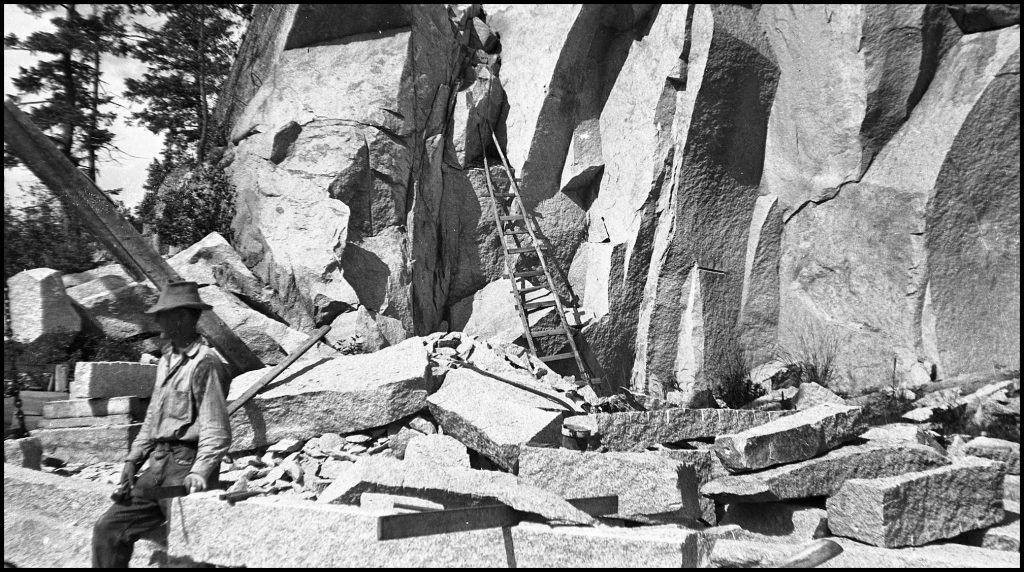

A camp was established to the south of the quarry site, and a blacksmith shop with hand operated bellows was built just north of the quarry. The company’s blacksmith was a powerfully built Frenchman named Bouchard, while their original cook was an old-country man named Tom Oddie from the west side of Okanagan Lake. Before a month had passed, however, it became painfully apparent to the whole crew that Oddie’s top card was not cooking. Oddie’s replacement was an excellent cook named Dick Edwards. Edwards must have been an industrious individual to feed the fifteen (plus) man crew three hot meals per day, under conditions that were decidedly primitive.

There being no road, all supplies were transported to the Lefroy Quarry by boat. The granite was moved to the rail-head at Okanagan Landing with the use of a small steam tug and a barge owned by Shannon’s Mill.

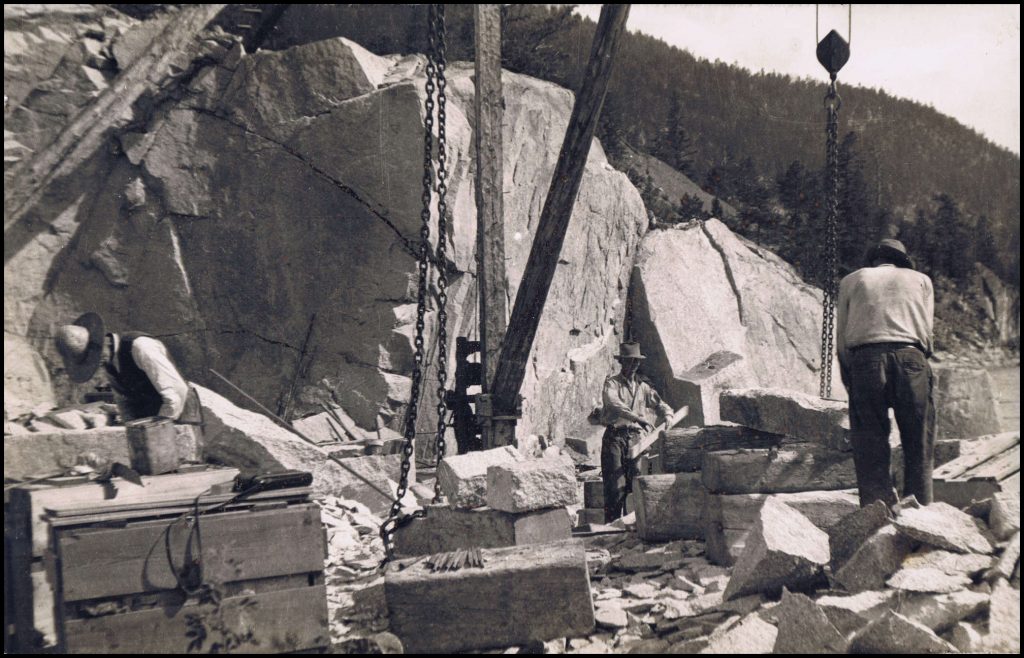

The actual quarry gang consisted of two quarrymen and a dozen or more stonecutters. The two quarrymen, Alex Hamilton and Jack McKinnell (spelling of McKinnell uncertain), were responsible for all the drilling and blasting. The stonecutters were mostly Scotsmen who had been apprenticed in Scottish granite quarries.

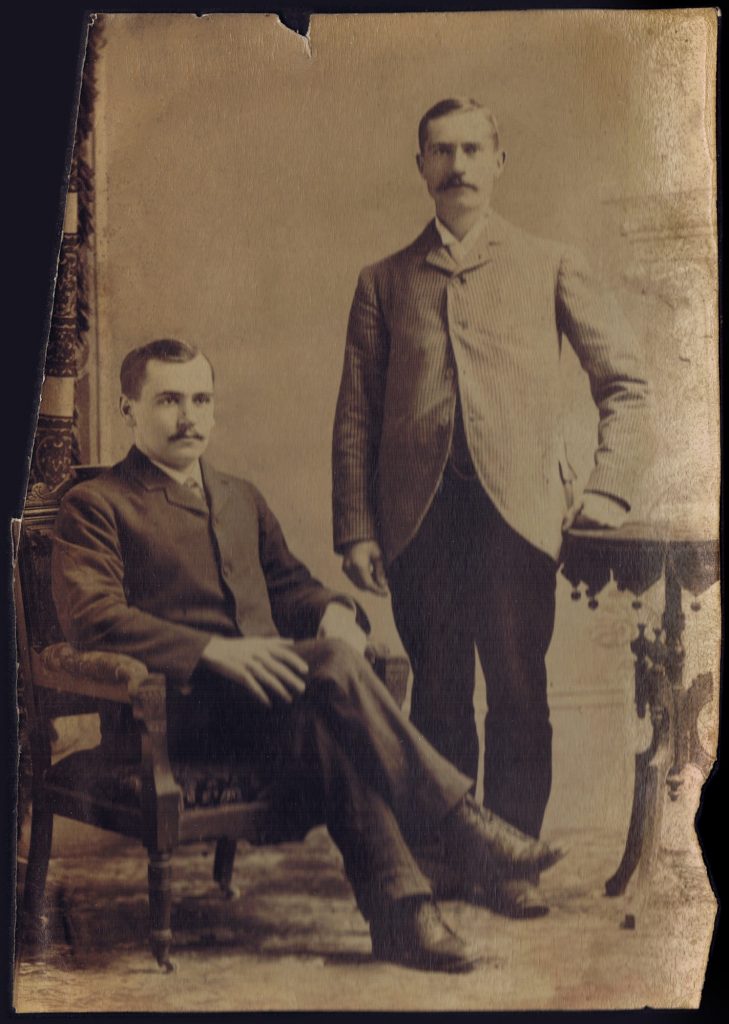

They included Bill Inkster, Jack Hannah, John Russell, Bob Hannah, Al Davis, Jack Burke, Jimmy Robb, Jimmy Glencross and Bill Mason. These quarry jobs were all unionized, with the stonecutters and quarrymen belonging to the A. F. of L. A quarry day was eight hours, 5½ days a week.

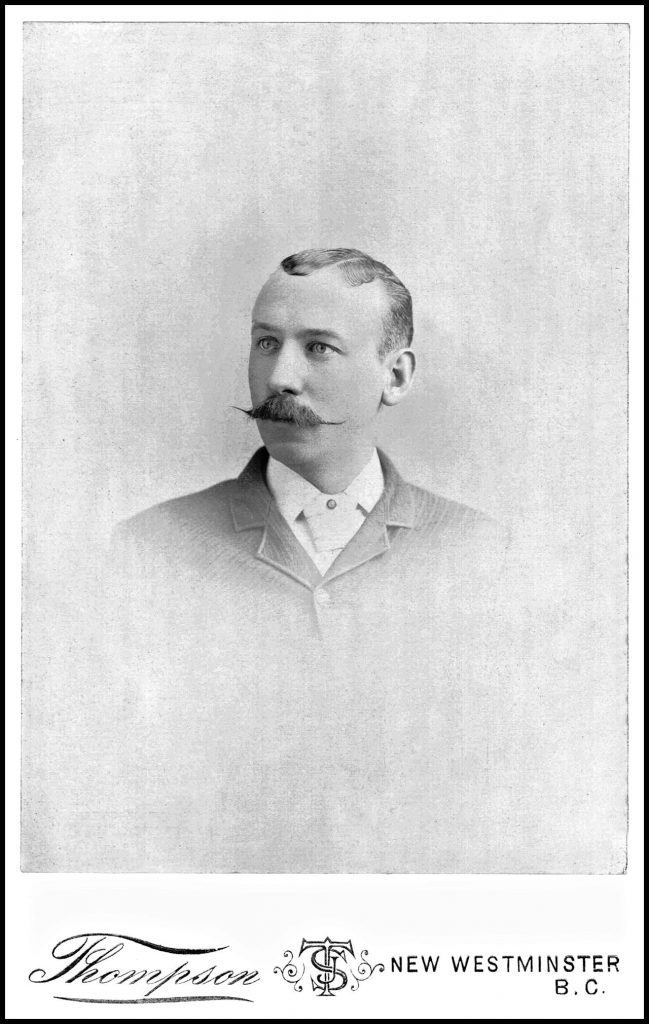

Billy Inkster – [Image courtesy of Vernon Museum & Archives]

The quarrying season in the Okanagan Valley generally lasted from mid-March to mid-November. The severity of the winter weather was the limiting factor. All granite is slightly porous and all unquarried or freshly-quarried granite contains a limited quantity of moisture throughout. When this moisture becomes frozen the stone is difficult to split or work. It was for this reason that quarries were not worked during the winter months.

According to William Parks, “the [Lefroy] stone [had] a good rift and grain; it [worked] easily under the hammer, and [was] practically devoid of knots or flaws , . . The weight per cubic foot, in pounds: 162.57.” [4]

The pink granite from the Lefroy Quarry was used to varying degrees in the construction of the following buildings: the present C.P.R. station in Vernon; the Church of England, Kelowna; the Royal Bank, Kelowna; the former Hudson Bay Co. Store, Vernon (northwest corner of Barnard Avenue and 32nd Street); and the “old” Post Office, Vernon (northwest corner of Barnard Avenue and 30th Street).

The Vernon Post Office was started early in 1910, and completed the following year. All granite destined for this structure was cut to size, and finished to specification at the quarry site. When the structure was completed, the quarry had become so depleted that the last of the Post Office stone had to be obtained from loose granite on the beach. According to Parks, between 6,000 and 7,000 cubic feet of granite had been removed.

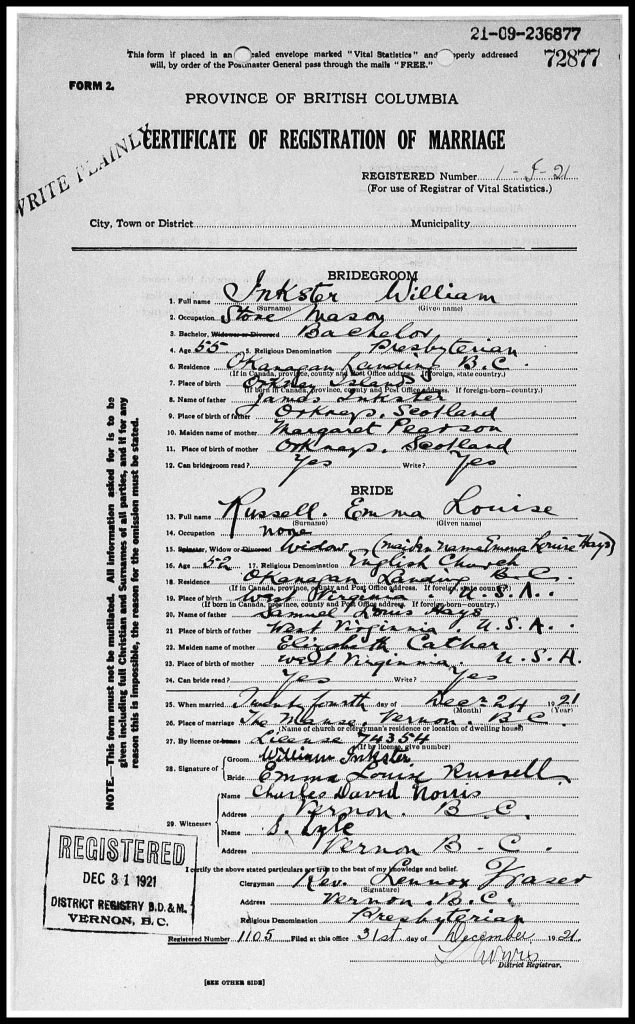

Late in 1909, John Russell journeyed to California for a big stone-cutting job, leaving his wife and family at home in Vernon. He did not return to the Okanagan, but died in California. Bill Inkster looked after the Russell family and eventually married Mrs. Russell.

The move to a new quarry site was made in 1911, prior to the Provincial Courthouse construction job in Vernon. The site chosen by Inkster was a mile or more south of Cameron’s Point, and 3 miles north of Carr’s Landing on land owned by Price Ellison, then the local M.L.A. and Provincial Minister of Finance and Agriculture. Ellison received a footage royalty on all stone removed. Inkster moved his new family to a site that would be within walking distance of the new quarry. He built a frame bungalow just south of the present site of Howard Russell’s house. The new quarry camp was situated in a bay between the Inkster house and the quarry, on land presently owned by the Alan Trethewey family. During the Courthouse job, this camp housed about 35 men. It consisted of one large bunkhouse, a cookhouse manned by Dick Edwards and outbuildings. The men walked over the sawback ridge separating Inkster’s Bay from Quarry Bay each morning, again at lunch, and again at quitting time.

In 1911, the point of land that was to become the new quarry was a large outcropping of silver-grey granite rising almost vertically out of the depths of Okanagan Lake to a height of fifty feet. Most of this out-cropping was blasted out and hauled away over the next three years. Today, the abandoned site is 80 to 100 feet long, running parallel to the lake and extending eastward some 50 feet. According to Wm. A. Parks (1917):

‘The rift of the stone is vertical at north 15° East and therefore is not parallel to the main jointing. The grain is horizontal. I am informed that very little difference in splitting is observed in the three directions; – rift, grain and hardway. Knots are practically absent…..Weight per cubic foot, in pounds: 164.30’. [5]

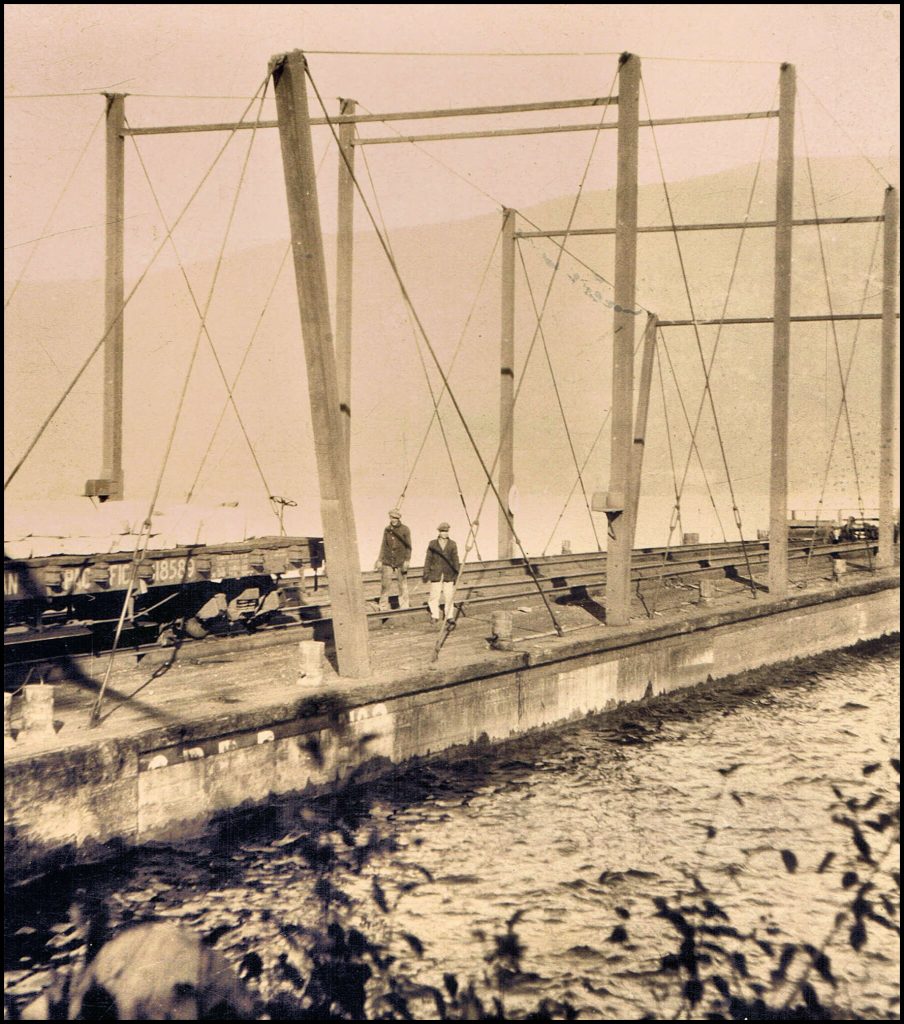

The Courthouse granite was quarried to rough specifications by Inkster’s crew, and shipped by C.P.R. lake service to Okanagan Landing, and thence by rail to Vernon. A C.P.R. tug, usually commanded by the well-liked Captain MacKinnon, would bring in a barge laden with railway flat-cars and remain with that barge until the loading was completed. The stone was loaded directly onto the flat-cars with the aid of the heavy quarry derrick. During the fruit shipping season, when the barge service was operating on a tight schedule, the stone was sometimes loaded at night, by the tug’s spot-light.

The two largest pieces of stone ever removed from this quarry (known as the Inkster Quarry), were destined to be the lintel stones capping the vertical frontal columns of the Courthouse. With utmost care and difficulty, the quarry crew cut the lintels to rough specifications and loaded each aboard the CPR. flat-car. Each measured fifteen feet by three feet by two feet, and weighed over seven tons. The flat-cars were oft-loaded at Okanagan Landing, and taken on the train to Vernon, where the real difficulties began. The teamsters were unable to haul the stones up the hill from the railroad tracks to the Courthouse site. The Courthouse contractor had considered taking them by rail to the north end of Vernon and using the teams to haul them back along 27th Street, but that street was so soft and muddy in most places, that it was not attempted. In the end, the contractor was forced to split each of the two lintels in half, lengthwise!

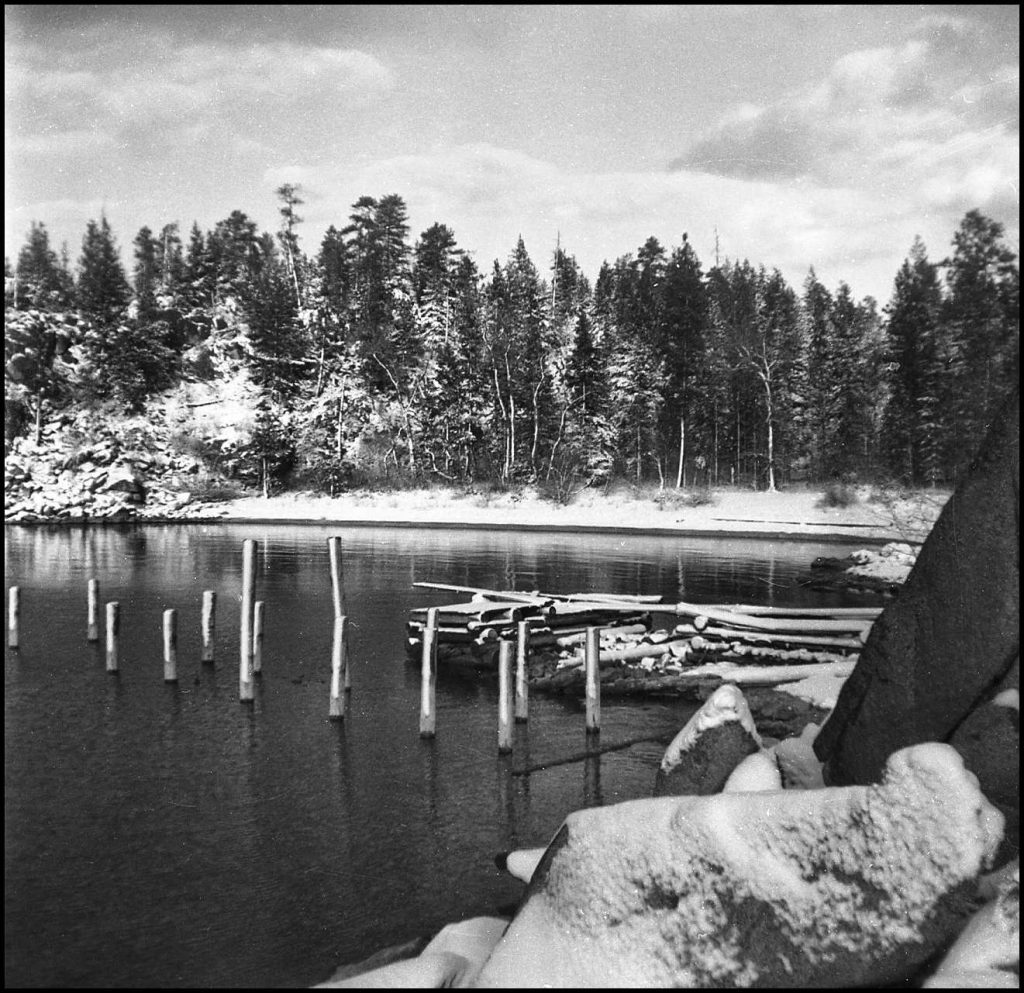

At the beginning of the Courthouse job, Inkster applied to the appropriate authorities to have his new home-bay designated an official C.P.R. landing, under the Federal Navigation Act. In due time his request was granted and he received an official document confirming the presence of “Inkster’s Landing”. The sternwheeler “Aberdeen” made regular stops at Inkster’s Landing to deliver provisions to the camp cook. In the absence of either a wharf or dolphins, the sternwheeler nosed gently up on the gravel beach at the head of this narrow bay. The provisions were then passed down from one of the large side cargo doors to a man in a rowboat alongside.

Following the Great War, a log cribbing filled with sizeable pieces of scrap granite was installed on the east side of the bay, as a wharf and breakwater. The first attempt by the large sternwheeler, “S. S. Sicamous” to reach the new wharf ended with the Sicamous’ bow jammed upon a rock outcropping at the northeast corner of the bay. Although able to extricate his boat without serious damage, the Sicamous captain requested the immediate installation of at least two dolphins, to prevent a recurrence of the incident. Inkster didn’t feel their small company could afford the $700.00 necessary for the work, and so ended “Inkster’s Landing” as a C.P.R. port-of-call. There was a wide trail, called a government road, between Okanagan Landing and Inkster’s Landing running along the bottom of a narrow valley between the present road and the Commonage Road. Supplies were henceforth brought in via this road.

The location of Inkster’s Landing

Following the completion of the Courthouse in 1914, and for the duration of the Great War, insufficient quantities of granite were being shipped from the Inkster Quarry to warrant a special stop by the CPR. lake-service. Inkster cleared this obstacle by building a rough, box-like barge capable of moving two tons of granite, very slowly! A double-ended clinker-built boat, powered by two sets of oars, was used to tow the barge to the nearest C.P.R. wharf on the east side. That was the Carr’s Landing wharf, three miles south. Arnold Russell recalls leaving the quarry after breakfast with his younger brother Jim manning the second set of oars. By rowing steadily they could have the boat and barge to Carr’s Landing by late afternoon. After the stone was stacked safely on the wharf, the brothers would leave the empty barge secured to a tree on the beach, and row home for a late supper. The following morning they would row back to Carr’s and collect the barge. It may be of interest to note that Inkster cut and lettered Reverend Philip Stock’s headstone during this period. The stone was delivered to Nahun landing in two pieces (cross and basse) and was later transported up the steep switch-back trail to Stock’s Meadows, on a single pack-horse.

Vernon Granite’s first power boat was purchased second-hand from Mrs. Oswald Pease of Ewing’s Landing in 1919. It bore the name “Grace Darling” when purchased, and this name was retained. It would appear that the “Grace” was originally one of the first boats on the lake powered by an internal combustion engine. In any case, it provided welcome relief for the chore of pulling the stone barge. When Jack Russell married Laura Tronson in the early 1920’s, Jack’s good friend, Mrs. Dudley-Ward of Carr’s Landing, gave him her boat for a wedding present. It was an eight H.P. double-ender named “Turn Turn” and being more powerful than the old “Grace Darling” inherited the duties of towing the stone barge.

In 1923, Inkster built a larger, heavier barge measuring 30 ft. x 12 ft. x 3 ft., capable of hauling twelve tons. A custom built Turner boat, 20 feet in length with a vertical towpost stepped amidship, was ordered from Vancouver. The C.P.R. delivered it to Okanagan Landing on a flat car. This boat was also named “Grace Darling”, after the then retired Pease boat. It was powered by a single-cylinder Easthope engine built for towing. The new “Grace” soon gained a fine reputation as a first rate rough-water vessel. She was well over forty years old and still going strongly in the late 1960’s. One night during a storm her mooring lines let go and she broke up on the rocks in Inkster’s Bay.

Billy Inkster [Image courtesy of Vernon Museum & Archives]

Following the courthouse construction, granite was used on smaller construction jobs. Parks reports the following prices quoted by Inkster, f.o.b. the quarry:

Sills up to 7½ in. high. 10 in. on bed, plain or lug, per lineal ft – $1.75

Sills up to 7½ in. high, 12 in. on bed, plain or lug, p.l.ft. – 2.00

Window heads up to 12 in. high, 8 in. on bed, plain or lug p.l.ft. – 1.75

Window archstones, 12 in. by 14 in. by 6 in., each – 2.25

Cut ashlar, 12 in. high, 8 in. on bed, 4-cut, p.l.ft. – 2.00

Cut ashlar, 12 in. high, 8 in. on bed, 6-cut, p.l.ft. – 2.25

Doors sills, up to 2 m. rise, 12 in. tread, 4-cut, p.l.ft. – 2.50

(Over 12 in. tread, add 50 cents per foot for every 3 in.)

Rough blocks, random squared, per cu. ft. – .50

Rough blocks, dimension, per cu. ft. – .60

Lengths over 7 ft. up to 9 ft., add 10 per cent.

Over 9 ft. special prices. [6]

By 1917, 30,000 cubic feet of granite had been shipped from the Inkster Quarry.

Following Jack Hannah’s death overseas in 1915, a half-interest in Vernon Granite and Marble was passed on to his brother, Bob. In 1919, Arnold and Jack Russell purchased a quarter section of land plus a fraction including the Inkster Quarry from Price Ellison. Jack was seeking good farm land and received that portion of the land which seemed best suited. He built a cottage on the present site of Mr. & Mrs. Trethewey’s house; with a log barn about a hundred yards north. Arnold took the quarry fraction, as well as a parcel to the south of Jack’s house. Although Arnold now owned the quarry-site, he did not have any financial interest in Vernon Granite and Marble. He corrected this in 1923 upon his return from a lucrative stone-cutting job in California. He bought out Bob Hannah’s share in the business for $600.00 cash.

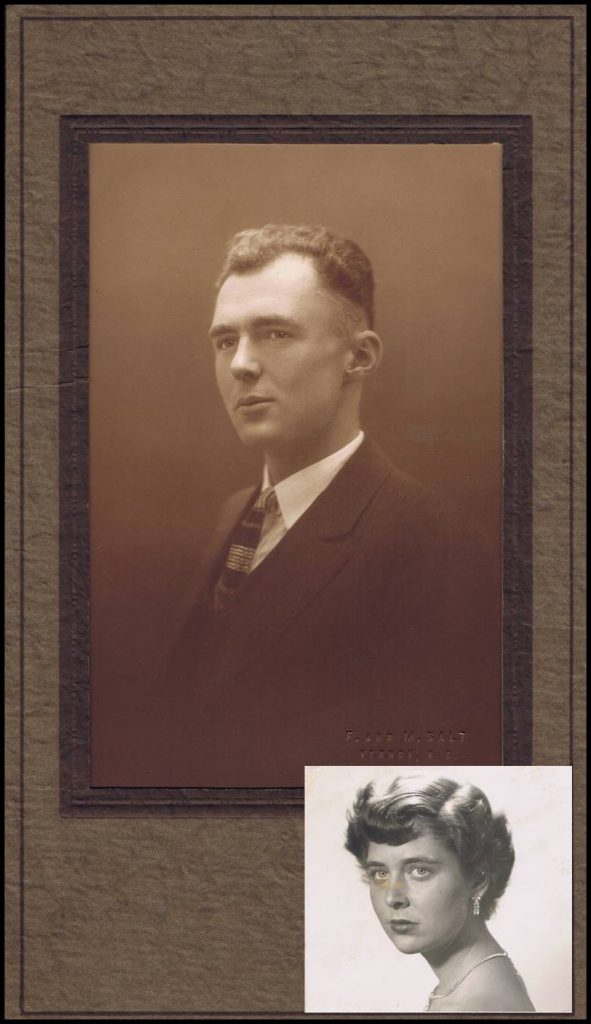

A photo of Arnold Russell in his 20’s.

The inlay at the bottom is of his

daughter Gay at the age of 18.

The advent of compressed air, following the Great War, introduced a new era in the stone trade. This new era sounded the death knell of the old-time stonecutter. Quite suddenly, in the space of a few short years, many of the stone cutting skills so painstakingly acquired by the old-time stonecutters were totally obsolete. New skills, doubling or even tripling overall production had to be acquired, in a trade that had seen no significant changes in 200 years. Any stonecutter unwilling or unable to cope with the rapid changes found himself unemployed. Arnold Russell had worked extensively with compressed air tools in California, and realized their great labour-saving advantages. Vernon Granite and Marble purchased their first air compressor in 1924, prior to the construction of the Vernon Cenotaph. It delivered thirty lbs. of air and powered their plug-drills and bushing hammers.

The initial heavy drilling in the quarry, for blasting purposes, still had to be done by hand in the mid-twenties. An age-old technique known as “double-jacking” was employed. Two men alternately swung seven pound hammers, while a third man turned the drill bit to keep it from jamming.

The splitting up of quarried blocks of granite involved drilling a row of holes along the desired line of cleavage. Once this was accomplished, two shims were placed in each hole with a wedge between. [7] As these wedges were tapped lightly with a small hammer, there was a great increase in pressure exerted into the stone along the desired line of cleavage. It was this increase in pressure that split the rock. Therefore, the speed at which a stonecutter was able to drill the ½” x 4” holes for the wedges and shims became rather crucial. By hand, an experienced stonecutter could drill one of these holes in 15 or 20 minutes, but with an air-powered plug drill, an inexperienced labourer could drill a similar hole in about one minute! This one example will serve to illustrate the significance of the technological revolution underway in the stone trade at that time.

The granite for the Vernon Cenotaph was quarried at the Inkster Quarry and finished to specifications at the Cenotaph site on 30th Street. Bill Inkster and Arnold Russell set up a derrick at the construction site for manoeuvring the heavier pieces of granite into place. The largest single component weighed five tons. The reason for finishing the granite at the construction site rather than at the quarry or the Price Street yard, was to increase the general public’s awareness of the project during the fundraising drive.

Billy and Emma in their latter years

Designer Richard Curtis modelled the Vernon monument after a similar, but larger memorial in Barrie, Ontario. The original plans called for a bronze statue to be placed at its zenith, but lack of funds prevented this. The corner stone and sealed copper box were laid on September 7, 1924, by Bishop Doull. A record of the box’s contents and the engraved trowel used by Doull during the ceremony are in the possession of the Vernon Museum and Archives. The overall dedication for the completed memorial was held on November 11, 1924. [8]

The Peachland and Coldstream War Memorials were both built by Vernon Granite and Marble. They also provided the granite for the Lavington Memorial, although it was cut and set by stonecutter, Bill Mason.

Arnold Russell next to his old work truck and Billy Inkster, photographed in 1937

Most of the stone removed from the Inkster Quarry during the next three decades was for mortuary monuments. After buying out the retired Bill Inkster in 1930, the business was conducted by Arnold, with help from his younger brother Howard. But the quarry was permanently closed in 1956, when Arnold contacted silicosis, brought on by the inhalation of excessive amounts of granite dust. Although retired, Arnold is likely the last stonecutter in the Southern Interior capable of doing both lead-lettering, and hand-carved granite and marble lettering. [9] Stonecutting, as a trade and an art, is almost gone forever.

FOOTNOTES

1. “Hays” was Emma Russell’s maiden name.

2, This quarry may still be seen below Dr. H. Alexander‘s residence. Permission to view this site should be obtained from the Alexander family.

3. About 1911, the Vernon city-fathers persuaded Vernon Granite and Marble to move their stoneyard from its original location to Price Street (near the present site of Kal Tire). As it had been, one of the first impressions a newcomer by train had of Vernon, was the rows and rows of freshly cut tombstones in the stone company’s yard.

4, Canada, Department of Mines, Report on the Building and Ornamental Stones, Vol. 5. 1917.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. These wedges and shims were more popularly known as “plugs and feathers”.

8. The original site of this memorial was about forty feet closer to 30th Street than it is today.

9. Since the introduction of air tools, most stone lettering has been done with sand blasters and pre-cut stencils.

CREDITS

Many thanks to Arnold Russell for providing much of the information presented here. Thanks also to Mr. J. Shephard and Mrs. H. Gorman of the Vernon Museum and Archives, for their help in tracing certain names and dates. Also interviewed were Howard Russell, Gay (Russell) Burgess, Mr. & Mrs. Alf. Brewer,

Dr. H. Alexander and Dr. H. Campbell-Brown.

© David G Falconer

……………………………………………..

Members of the Russell family would like to say a huge thank you to Alice Lee and Gilda Koenig, of the Vernon Museum & Archives, for taking the time to locate and pass on to them the three portrait photos of Billy Inkster used within the text above.