Some History of the Craigie Family

by

W. T. CRAIGIE

11th March 1980

Introduction: My Craigie relatives of the older generation used to claim that the Craigies had royal blood in their veins. My own generation paid no attention;’ there were no signs of royalty in our way of life. My father’s cousin, Peggy Yuille, in the last years of her life, urged me to trace the family history. Someone in Edinburgh had done it before; she couldn’t remember who, but she said it was worth doing. She died in her eighty-eighth year. After her death, I started digging into old books and records relating to the Craigie name. I have scanned the records at Register House, Edinburgh, and I have read various history books in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, and the National Library, Edinburgh. The result of my researches was inconclusive but the exercise itself was very interesting to me, and I write these notes in thye hope that others of the family may find them equally interesting. Indeed, they may be able to fill in some of the gaps which I have been unable to fill.

There are substantial gaps in the records at Register House and some are so badly written as to be illegible. No records for the Orkney Isles exist prior to 1657. At that time the Orkney records were shipped to Edinburgh but the ship and its contents were lost in a storm at sea. Thus it appears impossible to establish any link which my family had with the shadowy “Blue-blooded,” ancestors who lived in Orkney in the fifteenth century other than accept the word of my older relatives that our family is in the direct line of succession and that my father was the oldest son, of an oldest son – and so, to the beginning of the line.

The investigations proved to be interesting. Members of the Craigie family were big fish in a little pond in Orkney for three hundred years. Since then, they have become little fish and middling sized fish, but occasionally a fair sized fish has surfaced. Sir Alexander Craigie edited the Oxford Dictionary and a Norse Dictionary; Sir Robert Craigie was ambassador to Japan from 1938 to 1941. Another Sir Alexander Craigie wrote a Primer on the poet Robert Burns in 1896.

The Orkney Craigies appear to be descended from James Cragy of Hupe and from their mother’s side, descended from the Norse Earls of Orkney and the Kings of Norway. It has also been surmised that James’s wife was also descended from the Stuart and Bruce royal lineage through David, Earl of Strathearn, who was the legitimate oldest son of King Robert II and Euphemia Ross. It appears more likely that James of Hupe’s bride was descended from the previous Strathearn line which was extinguished when the Earl of Strathearn was killed at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 [part of the Second War of Scottish Independence, near Berwick-upon-Tweed.] This Earldom reverted to the Crown and was given to the aforementioned David.

CHAPTER 1

The name Craigie indicates that it was a name of territorial origin and it was spelt variously – Cragy, Cragyn, Craguli, as well as the more modern Craigie. The earliest reference to the name concerns Johan de Cragyn of Linlithgowshire who rendered homage to the English King Edward I in 1296. He did this along with two thousand other Scottish landowners (including Bruce) under duress in order to retain his lands. In history, the list of signatures was known as the “Ragman’s Roll”. His seal bears the device of a winged griffin respecting.

Craguli appears to be Craigielea. The ruins of Craigie Castle lie on the farmlands of Craigie Mains near the village of Craigie in the parish of Craigie, in Kyle, Ayrshire. The property was carried by the heiress to Wallace of Riccarton (Richardston) who became the Laird and was known as Craigie. Adam Wallace of Riccarton was the cousin of Sir William Wallace. His descendant, known as Craigie, was second in command under Hugh Douglas, Earl of Ormond at the Battle of Sark, 1448 [Part of the Anglo-Scottish Border Wars at Gretna, Dumfries and Galloway]. The victory over the Earl of Northumberland’s army was achieved principally owing to the judicious conduct and intrepid valour of the gallant Laird of Craigie who died of his wounds after the action.

Bryce de Cragy was a Burgess of Edinburgh in 1317. John de Cragy obtained a charter for the lands of Merchamstom (Merchiston) Edinburgh in 1367 and rendered homage to Robert III in 1371. He sold some, or all, of these lands before 1400. Alexander de Cragy was Bailie of the Templelands of St John, Ayr. Persons of this name early made their way to Orkney, where John de Krage appears as one of the prominent men in 1427, and Craigie of Gearsay were a family of long standing in the islands.

Craigie Place Names

The parish of Craigie in Kyle, Ayrshire, contains the ruins of thirteenth century Craigie Castle, Craigie Mains farm, and the village of Craigie with its old church and graveyard, inn, and surrounding houses, many of which are modern better-class ranch style bungalows. The early thirteenth century castle stands on a small eminence commanding wide views of flat farmland fields in all directions. The most of two walls of the main building face each other and contain handsome inside window frames with steps leading up to the small window apertures. Below each of these high windows is a line of loopholes. The collapsed curtain wall lies scattered round its original position with only the entry gate walls standing. This was the castle of the Ayrshire Craigies. It stands in the modern Craigie Mains farm lands. This farm has a large house which is almost a mansion, as well as a very nice bungalow nearby. The Kilpatricks who own the farm used to have the finest stud farm of Clydesdale horses in Britain. Now, they have an attested herd of Friesian cattle.

The small village of Craigie in Perthshire lies about a mile off the road between Dunkeld and Blairgowrie. It stands high above a small loch which contains an island upon which stand the ruins of Clinie Castle. It is a very small village but the view over the loch to the northern hills is beautiful.

There is an even smaller village of Craigie a few miles north of Aberdeen, and there are districts of Craigie in Perth and Montrose.

The Orkney Craigies have no places named after them in the Islands. The lands they held retained their original Norse names, such as Rousay, Wyre, and Gairsay.

Craigie Hill Fort is an iron-age fort lying adjacent to Cramond, near Edinburgh. Nearby, is Craigie Hall, a building of some age, now used as Headquarters of Scottish Army Command.

The poet Longfellow lived in Craigie House, Boston. There was a James Craigie who lived at the time of the American Revolution and was known as a roué. Whether the house descended from him, or from some other Craigie in America, is not known but it indicates that Craigies settled in America in Colonial days in the nineteenth century – possibly from Orkney?

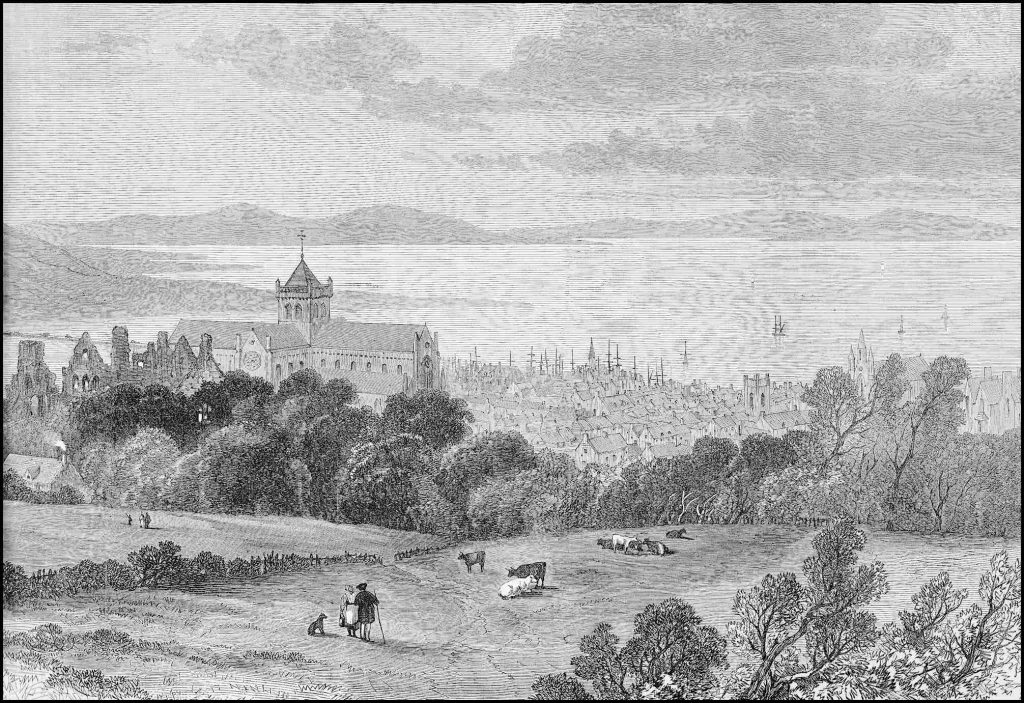

Orkney Craigies

No firm date can be traced of when the first Craigies went to Orkney. The first date I can trace is contained in a document dated 1418, which refers to the “Auld Privilege of the Craigies.” Another refers to the Craigie brethren. What took them to Orkney, and when? One can only guess. Henry Sinclair, Lord of Roslin, near Edinburgh, married the sole heiress to the Orkney Earldom, and became Earl of Orkney in 1379. He would need knights to assist him in the administration of the Islands (which were under the crown of Norway). Maybe, John de Cragy of Merchiston had met with hard times! He sold his lands! Manybe he had many sons to provide for, and younger sons had to seek their own fortunes. Neighbour Sinclair of Roslin may have provided the answer, or some of it! The Craigie brethren were settled with lands of Pow, and others, by 14th February, 1418, and by 1422 James of Cragy, Laird of Hupe, was married to the eldest daughter of Lord Henry Sinclair and his lawful wife Margaret, daughter of the late Earl of Strathearn. A testimonial (or passport) reads,

“James Cragy of Hupe, Goodman 1424, and Hirdman of the King of Norway, 1422, married Margaret, Eldest daughter of Henry St Clair before 1422. Testimonial given to James of Cragy by Lawman of Orkney, Canons of St Magnus, and citizens of Kirkwall, November 10th, 1422.

William son of Thurgys (Thorgil), Lawman of Orkney, Nicolas of Anyud, and Lawrence of Turay, Canons of St Magnus Church, John Magnusson, William of Erwin, Peter of Paplay, Walter Andresson, citizens of Kirkwall, testify that James of Cragy, dominus of Hupe, the bearer of these presents is a liegeman of the King of Norway residing in Orkney and that he is married to Margaret, lawful daughter of Elizabeth of Strathearne and Lord Henry St Clair late Earl of 0rkney ( Elizabeth being lawful daughter of the late Lord Malise of Strathearne, Earl of Orkney. The lawful birth of and the merits of James of Cragy are set forth, and it is particularly mentioned that he was the firmest supporter of the late Bishop of Orkney, John of Colchester, and endured many troubles through the adversaries of the said Bishop. The seals of the granters of this testimonial are appended at Kirkwall, November 10th, 1422.

Endorsement: Ane testimoniall annentes the auld privilege of the Cragys, aviss har (rest illegible.)”

The testimonial was probably written to enable James to travel to England. Earl Henry St Clair was in command of the expedition which set out to take the young Prince James (afterwards King James I) to France. Their ship was captured by the English off Flamborough Head and the whole party was kept prisoner by the English king for many years. During this time there were many comings and goings between Scotland and England, hostages exchanged, and negotiations for release made. James Cragy as kinsman of the Orkney Earl would almost certainly be involved. Beyond that he would have a leading role in governing the Islands during the absence of the Earl.

In due course, James’s eldest son John was appointed Lawman of Orkney, a position he held from 1455 to 1480. John’s son William succeeded as Lawman and held the position from 1480 to 1495, and William’s son John became Lawman from 1495 to 1509.

The Lawman was the President of the “Thing,” (Norse-type Parliament). He was the Keeper and Expounder of the Law book and Chief Judge of Orkney. The Lawman was, therefore, the chief magistrate under Norwegian law. An important part of his duty was to uphold the rights of the citizens under Udal Law and to keep the Law book. It has been said that the Scots Lawmen did not understand properly their duties and so the Norse “liberties,” were gradually eroded.

Under Udal Law when a landowner died his land was divided between all his children. Thus, in time, the land holdings tended to become smaller and smaller. In practice, one of the heirs bought out the other shares and so preserved the estate. The Lawman and his magistrates in council confirmed the settlement and registered it in the Law book.

In 1468 the Princess of Norway (and Denmark) married King James III of Scotland. Part of her dowry was the Orkney Isles and so, for the first time Orkney became part of the Scottish realm. But it was confirmed that the old Norse Law and privileges would be respected. In 1472 James III decreed that the fee of the Lawman was to be paid only on the authority of the king. In 1470 he contracted an agreement from the Earl of Orkney that the crown take over the Earldom. Lord Sinclair was given lands in Fife, at Ravenscraig, in compensation.

John Craigie continued to preside over “The Thing,” (the Orkney Parliament in which the king, earl, bishop, Odallers, and Odal born, were equals. In 1509 the office of Lawman passed out of the Craigie family. By that time, John’s son Magnus had become Laird of the whole Island of Rousay. In 1503 Sir Thomas Craigie and John Craigie were registered as Tacksmen of the lands of Quhan, Rousay, and James Craigie and his wife were Tacksmen of the Isle of Wyre. In 1564 Sir Nicol Craigie was Vicar of Holm. In 1580 William Craigie of Pabdale (Kirkwall) was Provost of Kirkwall and Commissioner to Parliament. Magnus Craigie was a Kirkwall councillor in 1580 and another Magnus was a councillor in 1615. (He officiated at several of the trials of witches.)

The Coat of Arms on the tombstone of Sir William Craigie of Gairsay, 1620, continues to show the Ermines of the Law as does that of Provost of Kirkwall, David Craigie in 1680. Patrick Craigie was Provost of Kirkwall in 1662, and other Provosts were Thomas Craigie of Saviskaill, 1548, William Craigie of Pabdale, 1624, and Hugh Craigie, 1690. As Provost each was Commissioner to the Scots Parliament representing the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall. Robert Craigie was a Member of Parliament to Westminster, 1742-7, but I do not know if he was a Provost.

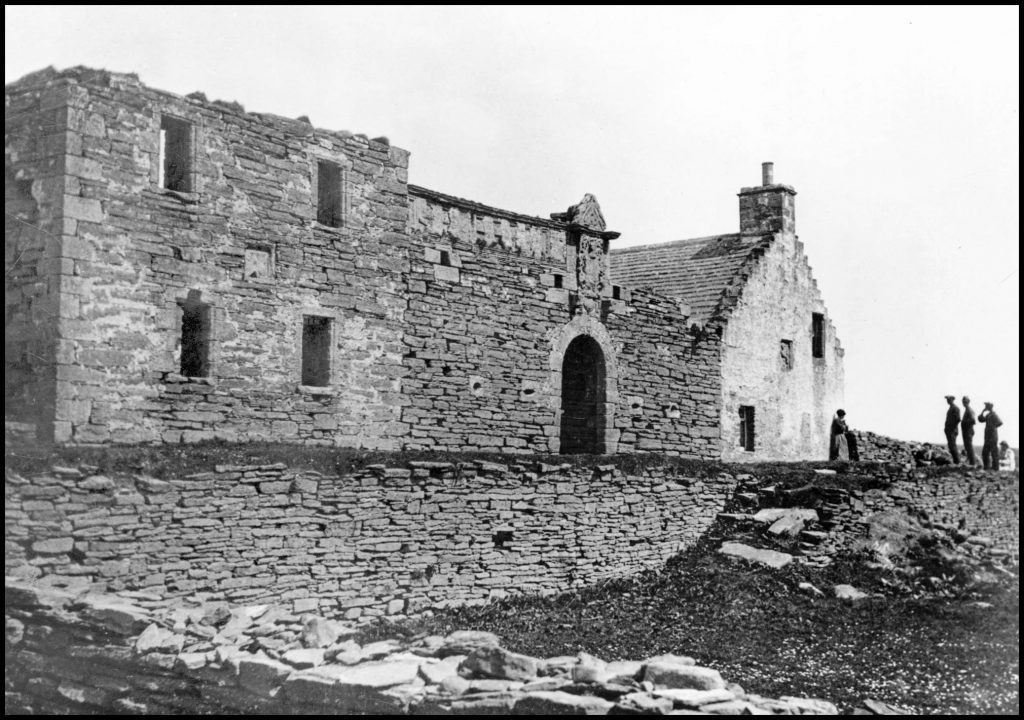

The Craigies of Gairsay were substantial merchants and landowners. Provost David Craigie of Oversanday, on his own behalf and on that of Hugh Craigie of Gairsay, paid the Bishop of Orkney for a seat in St Magnus Cathedral and for space to inter deceased members of their families, a cash consideration, and an undertaking to maintain the stained glass window [pictured below] bearing the Craigie arms above the plot.

In the year 1529 a battle was fought at Summerdale between two contending Sinclairs. The one was resident in Kirkwall. He was competent and well liked, but he was a bastard. The other, resident in Caithness, was legitimate but he was not well thought of by the Orcadians; he had the authorisation of the young Scottish King James V. He invaded the main island with a force of five hundred men which was totally wiped out by the resident army. Accepting the position, James pardoned the Orkney leaders amongst whom were James Craigie of Brough, John Craigie of Banks, Gilbert and William Craigie.

In 1704, William, oldest son of Sir William Craigie of Gairsay, was killed at the Battle of Blenheim. As his father was wealthy, William probably bought a commission. Lord Orkney (a Hamilton) and the troops under his command played a most significant part in the victory though suffering heavy losses. It may be that young William served under Lord Orkney.

The Craigies supplied many Lord Provosts to Kirkwall during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was necessary to be a man of means to be either a bailie [a municipal officer and magistrate] or a provost so the indications are that the senior branches of the family were in affluent circumstances. Moving with the times, they became merchants as well as landowners, or tacksmen. Rents were collected in kind and they traded with Scandinavia and the Baltic, exporting and importing. Sir William Craigie of Gairsay was the most successful; he owned land, ships, and money, and while he was esteemed as a good friend and neighbour, he liked power. For example, he claimed the right to nominate the provosts of Kirkwall although he shunned office himself.

Margaret Honyman, daughter of the Bishop of Orkney. Their initials adorn Sir William’s

family crest above the main entrance.

[Both images courtesy of Orkney Library & Archive.]

Patrick Craigie was the most colourful of the Kirkwall Provosts. He fought many diplomatic battles against the Earl of Morton to establish the rights and liberties of the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall. Here is his story.

Provost Patrick Craigie of Kirkwall

Patrick Craigie came of good stock. The Craigies were one of the oldest Scottish families in the Orkney Islands. His father, William, was a successful merchant who had served Kirkwall first as its Thesaurus [treasurer?] and afterwards as a bailie for twenty years. Patrick was the third son of the family. His mother, Marion, belonged to the Irving family, another Scots family whose roots were equally deep in Orkney history. His wife was Ann Ballenden, the daughter of another old Scots family. The lives of his brothers have not been recorded but Patrick’s name has lived on as a man of courage and resource who fought long and hard for the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall. He was born in 1620 when his father was treasurer of the burgh. Patrick was brought up in affluent circumstances and he received a good education at Kirkwall’s deep rooted grammar school.

The magistrates of the burgh in these days were men of substance; some were of Scots descent while others belonged to the old Norse families. Most of them were landowners, tacksmen, or merchants. They kept a strict watch over the affairs of the town and malefactors were punished severely. A man or woman convicted of petty theft was often ordered to be stripped to the waist and lashed with a rope by the hangman. Sometimes the sentence was carried out at the rampart on the shore, and sometimes the offender was paraded round the town and flogged to the beat of the town’s drummer at the Mercat Cross and at the town’s head. After that, some were banished from the town for life. Some were sentenced to the jougs [an iron collar fastened by a short chain to a wall, often of the parish church, or to a tree or mercat cross] and some were hanged. Convicted witches were sometimes burned to death. Thus order was maintained at this period in the seventeenth century.

To compensate for having to inflict such unpleasant sentences upon the common citizens these Justices of the Peace marked the occasions of national joy or sorrow: a sovereign’s birthday, a military victory or defeat, brought the Provost and Magistrates together to mull over and to discuss thoroughly the event. This they did aided by copious draughts of wine and brandy the cost of which was charged to the town.

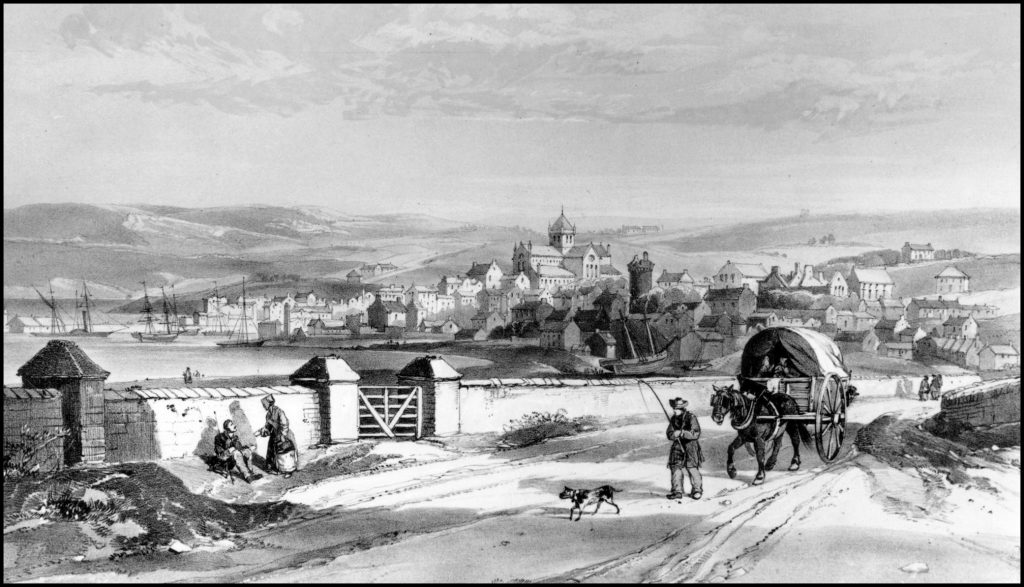

Kirkwall was not an ordinary town. It was a Royal Burgh, an honour conferred on it in 1468 by King James III when the Islands which were then Norwegian were impignorated to the Scottish Crown as part of the dowry of James’s Norwegian bride. This honour was confirmed by James V in 1540 and it was one of which the citizens of Kirkwall was proud. From 1468 the Earldom of Orkney belonged to the Crown but it was the custom of succeeding monarchs to lease the Earldom to a high nobleman who possessed at least some royal blood. Two such recent incumbents, Patrick and Robert Stewart, were executed in Edinburgh for rebellion but before Patrick Stewart was apprehended he destroyed all the Records of Kirkwall as well as the ancient Lawbook of the Islands. Thus Kirkwall, among other lost documents, did not have a copy of its ancient charter. [The young Robert Stewart was hanged for treason in Edinburgh on 1 January 1615. Patrick Stewart was beheaded, also in Edinburgh, on 6 February 1615: only after his efforts to evade execution by blaming his son for the uprising had failed. At the time the most damning indictment of his character was that his execution had to be deferred in order to give him time to learn the Lord’s Prayer, which he didn’t know. The Earldom of Orkney was extinguished with Patrick’s death.]

In the reign of Charles I the Earldom was leased to the Earl of Morton. After the inter-regnum of the Protectorate under Cromwell the Earldom was again leased to Morton by Charles II. The Earl set about mulcting the Islanders for as much as he could. He saw a chance of adding to his revenues by depriving Kirkwall of the revenues which as a Royal Burgh it was entitled to collect. It was during this period that Patrick Craigie came into the picture.

Some years after the death of his father, Patrick became a bailie which office he held until 1651 when he, along with all the town’s officers who were Royalist to a man, stood down. Cromwell’s army in Scotland under General Monk had invaded the islands and a military government was imposed. The military machine was effective in controlling the Orkneymen but it rode rough shod over them. It did not concern itself with the maintenance of the Burgh’s properties which, in particular, included the cathedral church of St Magnus. The burghers, seeing the deterioration of the town’s properties through lack of repair and control, called on the former magistrates to resume their duties but it was not until 1656 that these gentlemen were re-constituted and Patrick resumed his position as a bailie.

After much deliberation the councillors decided to try to come to terms with the Protectorate and to seek its co-operation so that they could resume their functions which included the levying of revenue in order that their properties might be maintained or restored. The Burgh lacked both a Town House and a Tolbooth, and the church needed repair both inside and outside. It was resolved to send a representative to Edinburgh and the man they chose was Patrick Craigie. By this time Patrick was thirty-eight; he was in his prime, handsome, strong, clever, and literate. He had eloquence and money and he impressed people. He did things in the grand manner as befitted one of the magnates of the Orkneys. The distance from Kirkwall to Edinburgh was the best part of three hundred miles and the journey could be made by sea, or by land and sea. On land there were only rude paths and travellers went on foot or on horseback hoping they would not be molested either by the soldiery or by brigands. On sea there were the dangers of storms and pirates.

Patrick crossed the Pentland Firth and from Caithness he made the journey on a hired horse. His mission took eleven months to accomplish and he returned to Kirkwall in July, 1659. He had been successful and he had secured an Act discharging Justices of the Peace and Others from encroaching on the Burgh which was to resume its liberties and to enjoy the same. The cost of the expedition was £2,119 7s 6d most of which was legal fees. His colleagues were very satisfied with the result and Patrick was appointed next Provost of Kirkwall.

In the year 1660 Cromwell died, the Protectorate ended, and Charles II came to the throne. Once more, the Earldom was leased to the Earl of Morton who was a Douglas and one of the leading Earls of Scotland. Morton did not live in the Orkneys. His chief interest in the Islands was to extract as much revenue from the inhabitants as he could and to this end he instructed his local representatives. Until this time he was empowered to tax the lands of the Earldom but not the lands of the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall which was entitled to collect its own taxes. The Earl decided on a plan to deprive Kirkwall of its rights and so to enhance his own revenues. The plan was to demonstrate to the Privy Council that Kirkwall had co-operated with the rebel Cromwellians against the King and that the Provost, Magistrates, and Councillors should be declared rebels, debarred from office, and all their estates confiscated. Using this charge and wielding his considerable influence in Edinburgh with his fellow peers he secured on the 21st November, 1660 an Order by the Commissioners of the Estates “Discharging the pretendit Provost and Bailies of Kirkwall.”

Meanwhile, in Kirkwall, in December, unaware of the Action in Edinburgh, but alive to the threat, the Kirkwall Councillors elected Patrick Craigie to be their Commissioner for Kirkwall in Parliament. He was instructed principally:-

To get maintenance for the Kirk,

To formalise the registry of Kirkwall as a Royal Burgh,

To authorise levies for the erection of a Town Hall and a Tolbooth,

To ensure that the system of weights and measures was not interfered with (as had sometimes been done by previous Earls in the past.)

[Orkney Library & Archive]

Early in January, 1661, William Young, the Earl’s servitor, appeared in Kirkwall and informed the Council that it was “discharged.” He then presented summonses against Patrick Craigie and the other officers of the Burgh namely the bailies John Edmundson, Thomas Wilson, George Spence and John Pottinger, and against Patrick Spence, the Treasurer. They were to appear before the Privy Council on 15th February. Young would not, or could not, provide written authority for his demands but he was treated seriously enough for action to be taken. The Burgh Fathers did not welcome having to undertake this trip in the dead of winter as it entailed travelling through the storms of that season when few ships ventured from port. Even the journey from Caithness to Edinburgh in the winter snows was a daunting prospect. The Provost rose to the occasion. He obtained the ready assent of his colleagues to go by himself and to represent them all. A week later he set out and attempted to cross the Pentland Firth from South Ronaldsay. Twice the vessel was driven back by storms but on its third attempt it managed to cross the stormy waters to Caithness.

Patrick had armed himself with sword and pistol, and he had sent both his man and his trunk by sea. On reaching Caithness he engaged the services of the Caithness Post, Hucheon Jock, to act as bodyguard and to take the hired horses back to Caithness after the journey to Edinburgh had been accomplished. The journey was not an easy one. They had to cross moor and mountain, river and flood, in rain, snow, sleet, and ice, in the depth of winter riding along rough tracks. After a journey of six weeks they reached Edinburgh on the first day of March.

The news which met him was disquieting. The Kirkwall men had been summoned to appear before the Council of the Estates on the fifteenth of February and as they had failed to appear the Earl’s Petition was granted. The Provost and Magistrates of Kirkwall had been denounced as rebels. Patrick had to act with care. If he was captured he would lose all his worldly goods as they were forfeit. Fortunately, he had friends who gave him shelter and subsequently found him lodgings. He was playing for high stakes and he decided to act a bold but cautious part. He ordered suits of clothes, shoes, stockings, and linen of the finest quality and thus clad in the height of fashion with golden garters and with roses on his shoes set about his business. By this time Hucheon Jock was on his way home but his own man had arrived. Patrick saw him suitably attired to accompany his flamboyant master. He visited lawyers and advocates and he met members of the Privy Council privately explaining his case and soliciting their support. He visited frequently the Convention of Royal Burghs and the Scottish Parliament on the town’s business, civil and ecclesiastical, all the while making friends and trying to enlist sympathy for his own and Kirkwall’s cause. Having thus softened up the ground he petitioned Parliament complaining of the Act which had been passed; he explained the cause of his late appearance and the true position of his town. Indeed, he explained his case so well that the Privy Council suspended the offending Act and Patrick found himself a man free to go about his lawful occasions. It was but a temporary triumph – the Act was only temporarily suspended – but he believed he had won total victory for Kirkwall, his colleagues, and himself. He threw a party, a kind of open house, for his friends and he paid a bill of £20 for strong ale. Then he caught a convenient ship at Leith and sailed home after a very eventful trip to the Capital.

The citizens of Kirkwall were delighted with the news that their officers had been re-established and Provost Patrick was the hero of the hour. He was suitably lionised. The only little fly in the ointment was that Patrick had funded these two missions from his own pocket. Up till that time Kirkwall had been without funds and had agreed to pay Patrick interest at the rate of six percent on the money spent which now amounted to several thousand pounds. The account remained outstanding and Patrick, who had perforce allowed his own business to languish during his long absences, found himself on the horns of a dilemma between public service and personal interest.

The Earl of Morton was not so easily beaten. He belonged to the inner ring of power in Scotland and he was on intimate terms with the key noblemen on the Privy Council. Craigie had not long left Edinburgh before the crafty Earl petitioned the Privy Council again to have the Kirkwall Councillors discharged from their duties. The Privy Council granted his Petition without bothering to summon to a Hearing or even inform the absent Orcadians of its action. Thus the Kirkwall Councillors proceeded with their duties unaware of the ban which had been placed on their activities.

The great Lammas Fair of the Orkneys was held at Kirkwall at the beginning of August. It had been held annually for generations and it was heralded by a procession of the Provost and Councillors through the streets headed by the town’s two drummers. The whole Council was present, proud to demonstrate that their rights as an ancient Royal Burgh had been recognised. On the Sunday, they occupied the Kirkwall magistrates’ seats in St Magnus Kirk for the same reason. The minions of Morton reported these deeds to their lord. This was his chance; he reported these misdemeanours to the Privy Council. Thus Provost Craigie and the Councillors were summoned for trial as rebels at Edinburgh on the twenty-third day of September, 1662.They made the journey by sea and encountered such rough weather that four hours after the ship reached Leith it foundered. Fortunately, the passengers were ashore before the vessel sank.

On the day of the Trial the Councillors appeared but their accuser, the Earl did not. It did not suit him. The Trial was postponed but it was agreed that Patrick should represent the other Councillors who were permitted to return to Orkney. Patrick then tried to have the matter settled out of court but the Earl would not agree. He also called at the Abbey at least nine times requesting to meet the President of the Council and each time he was refused. At last, the Earl’s agent arranged a date mutually convenient to both parties. Two days before that date the Earl arrived at Court and submitted his Petition. Not only was he admitted but also his Petition was upheld and Patrick Craigie, in his absence, was declared a rebel and put to the horn; he was now a fugitive! A Messenger-at-Arms called Carnegie was put on his trail and he had many lively moments escaping from this officer of the law.

Through his advocate, Patrick addressed a long letter to the President of the Council asking for justice. In it he wrote amongst other things that “In defending the Burgh for two years he had to neglect his own business: he had risked his life at sea during winter; his wife had died of grief leaving four motherless bairns. But though broken hearted, ruined, and unjustly declared a rebel, he was true to his trust and he would not betray the Burgh. The Earl had no just reason to persecute him anent what he had done to defend the privilege of Kirkwall. The Earl had not even met him in his lifetime.” He kept his advocates busy trying to get the sentence suspended but without result.

A new door opened. During his social occasions he had chanced to meet influential ladies friendly with the Earl but sympathetic to his plight. They gave him advice which he followed. Accompanied by the Laird of Glentochie and a Mr Buchanan and their servitors they called on my Lord of Morton at his house at Aberdour where, strangely enough, they were entertained for a week. During this time Patrick did his best to come to terms with his noble aggressor and he took the liberty of offering to his Lordship a fine gun and twenty-four pounds in cash as a placatory gesture. The Earl was graciously pleased to accept but he still drove a hard bargain. If Craigie would cease to try to have the decision against him reversed, the Earl was prepared to call off the Messenger-at-Arms and Craigie could return to Orkney. Patrick agreed and took ship for Kirkwall.

The Kirkwall Councillors continued in office, but with the help of the lawyers whom Patrick had retained, negotiations were continued in Edinburgh. During Patrick’s visits to the Capital “ane large parchment,” had been discovered in Edinburgh Castle which put Kirkwall’s case as a Royal Burgh beyond doubt, but it was not until 1668 that the Charters were finally confirmed and the decrees against the Burgh suspended. The Lords of the Treasury gave an order to the Earl of Morton “not to meddle with the town of Kirkwall or its inhabitants.” The Orkney Islands reverted to the Crown and the Earl of Morton was relieved of the Earldom of Orkney. An Act of Parliament of 1670 confirmed Kirkwall’s rights.

Thus Provost Patrick Craigie’s efforts on behalf of his native town were finally successful. His own affairs, however, had been neglected. The total money advanced by him, £7,328 15s 4d (most of which had been expended on legal fees and maintenance) was not repaid for many years and his business was ruined. He had become further embarrassed by standing security for some friend who defaulted and Patrick could not lay his hands on the money to pay up. He was put in the Tolbooth as a debtor. Later, in 1675 he was asked to fulfil a mission to Edinburgh on the town’s behalf – his fourth one! The result was said to be satisfactory. His health failed and his affairs failed to prosper; he got into debt several times and he spent his last days in the Tolbooth where he died on a Sunday morning in February, 1682. All his days he had lived in the grand manner, dressing and behaving like an openhanded lord, handing out gratuities and presents as the occasion demanded. In the end, he died in prison owing the basic sum of sixteen pounds and thirteen shillings.

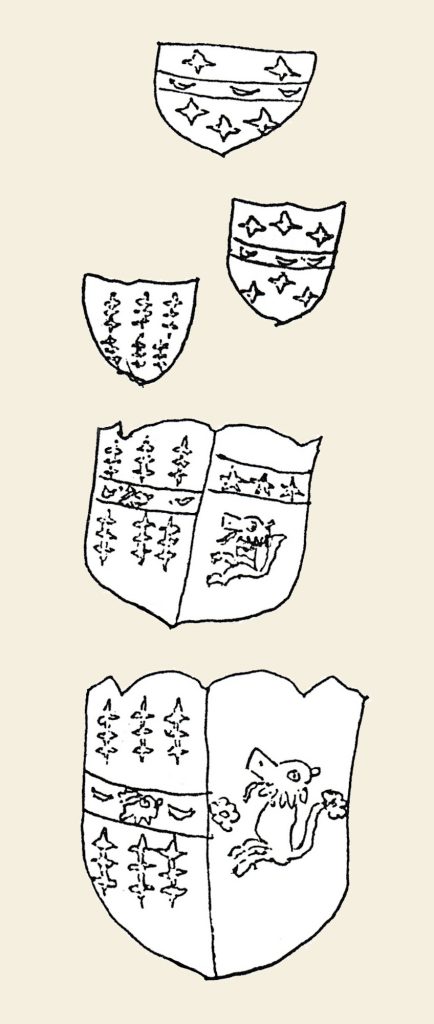

Heraldic Coats of Arms

Johan de Cragyn. (1297 A.D.) His seal bore the sign of a Winged Griffin respecting “de Craguli.” A Winged Griffin means “Vigilance.”

James Cragy of Hupe. (1422) (from stained glass window in St Magnus Cathedral.)

John Cragy, Lawman of Orkney. (1455). (son of James Cragy of Hupe) On a fess between six stars (three in chief and three in base), three crescents. Legend illegible.

Margaret Cragy. (1611.)

Sir William Craigie of Gairsay. Impaling Halcro of that ilk (1620). Ermine on a fess, a boar’s erased between two crescents impaling Halcro.

David Craigie of Oversanday, Lord Provost of Kirkwall and Commissioner to Parliament. Married Margaret Graeme, circa 1680 A.D.

Notes. Sir William Craigie of Gairsay (17th Century Tacksman and Merchant) built a handsome mansion on Gairsay. It is not possible to ascertain to which of the three lines of family he belonged.

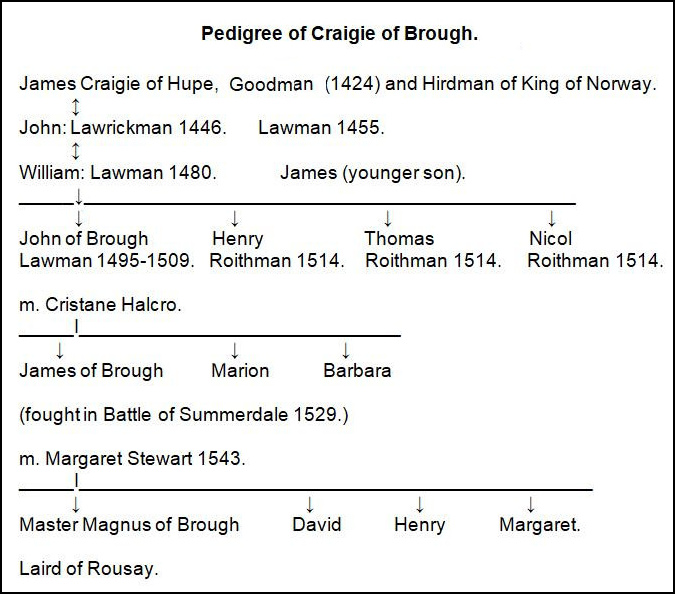

Roithman (Norse): Magistrate.

Lawman (Norse): Chief Magistrate and Keeper of the Lawbook of the Orkneys.

Norse Earls of Orkney

Harald Maddadson, Earl of Orkney (and a descendant of the Kings of Norway). His daughter married Gilbride, Earl of Angus, and his descendant, Isabella, daughter of Magnus, the last Norse Earl, married Malise, Earl of Strathearne, who was killed at the Battle of Halidon Hill, (1333.)

Angus Earls of Orkney

Gilbride was the first Angus Earl, a Scot, with a Norse wife (mentioned above) to whom he owed the succession to the Earldom of Orkney.

Strathearn Earls

Malise, Earl of Strathearn, (another Scot) married Isabella and through her lineage became Earl of Orkney. He was killed at the Battle of Halidon Hill (1333). His son Malise, Earl of Strathearn, Caithness, and Orkney, married

(1) Johanna, daughter of Sir John Menteith, and

(2) Marjory, daughter of Hugh, Earl of Ross (circa 1350).

Malise had no male issue but his daughter Elizabeth married Henry St Clair, Lord of Roslin, who was made Earl of Orkney.

This Henry was the son of William St Clair, Lord of Roslin, who had married Isabella, the daughter of Malise, Earl of Strathearn.

The eldest daughter of Henry and Elizabeth named Margaret married James Cragy, Laird of Hupe, before 1422.

Note. With the death of Malise at Halidon Hill the male Strathearn line died out and the Earldom reverted to the Crown. David, the oldest son of King Robert 11 and Euphemia Ross became the next Earl of Strathearn in 1379.

Pedigree of the Craigie Family from the late Sixteenth Century

As far as I can trace no written records exist to establish the family connexions for two main reasons.

1. During the Earldom of Patrick Stewart, Patrick rebelled against the Crown and before he was apprehended and executed, he destroyed the Records of Kirkwall as well as the ancient Law book of the Islands (with the object of seizing the lands and properties which he coveted).

2. During the Cromwell Protectorate all the remaining records were ordered to be sent to Edinburgh for safe keeping. The ship in which they were dispatched sunk in a storm at sea. Thus the remaining Records were lost forever.

However, members of the Craigie family continued to display the Ermines of the Law on their Heraldic shields thus claiming descent from their Lawman ancestors.

Throughout the Seventeenth Century there were prominent Craigies – merchants, tacksmen, and provosts – who appeared to come from various branches of the family. Then in the Eighteenth Century there is no mention of a prominent Craigie with the exception of Robert Craigie of Glendoig who became Member of Parliament, 1742-47.

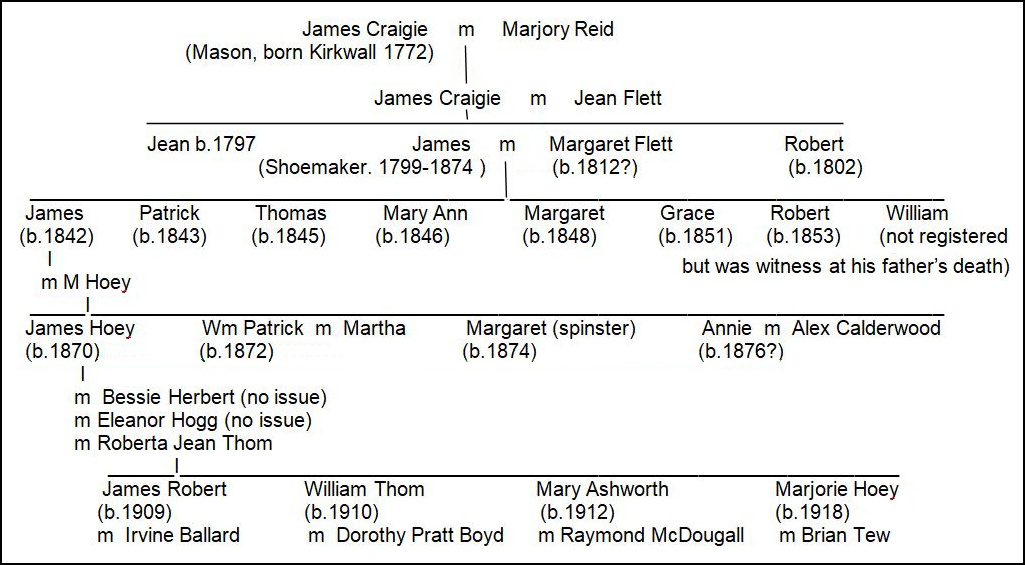

The Records of the Islands exist from 1657 but they are incomplete and some of them are illegible. I have scanned them in Register House, Edinburgh, and I have failed to trace my own descent further back than two hundred years. In spite of the claims of my older relations that my father was the head of the major branch of the family, I can find nothing to substantiate, or disprove it. It was owing to “hard times,” that my grandfather and his brothers left Orkney to seek their fortunes in Glasgow or Edinburgh a hundred years ago. Throughout the century prior to that our family were either artisans or tradesmen. How a leading family with several important branches should all lose their prosperity during the same period remains a mystery.

The family tree annexed is derived from these searches. The first James Craigie mentioned is the only one of that name which fits into the pattern but it cannot be substantiated. All the rest is substantiated.

It is possible that the other main lines of the family returned to the mainland of Scotland at various times during the eighteenth century as, apart from Craigie of Gairsay, no other main line Craigies appear in the registers of births, marriages, or deaths. Jim Inkster, the husband of the daughter of William W. Craigie, showed me in Kirkwall Cemetery the headstone of James Craigie (who was born in 1799). Jim became the junior partner of William in the latter’s cabinet-making business which involved extensive travelling throughout Scotland and England. Eventually, the trade declined and the business was wound up. The said William presented a handsome silver trophy for competition at Kirkwall Bowling Green which I saw during my visit.

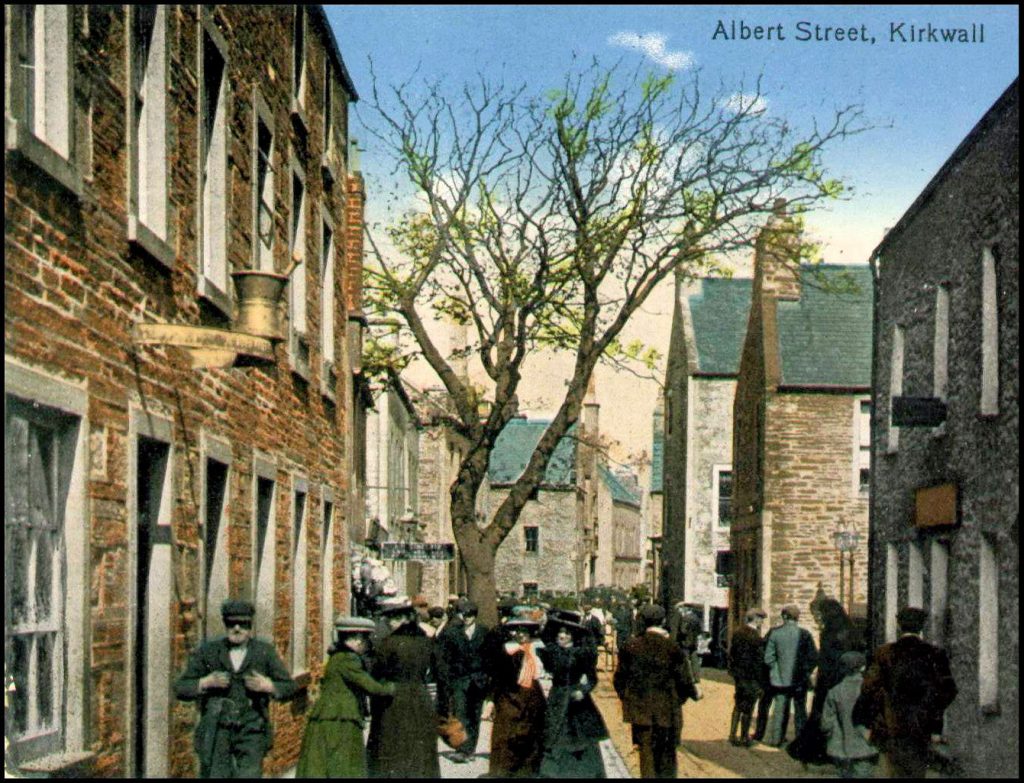

[James Craigie (1799-1874) married Margaret Hutton Flett (1811-1884) in November 1840. The 1851 census records James being a shoemaker in Albert Street, Kirkwall, employing four men. The two images above show both ends of Albert Street, the hand-tinted postcard showing the ‘big tree’ at the Cathedral end – and the other at the junction of Bridge Street, courtesy of Orkney Library & Archive.]

[The photo below shows the Craigie family headstone in St Magnus Cathedral graveyard.]

My grandfather, along with two brothers, migrated to Glasgow before 1870, while another brother went to Edinburgh.

Grandfather James became a salesman. He married Magdalene Hoey (of Huguenot ancestry) who came from the farm of Strathruddie, near Aberdour, Fifeshire. He became a sergeant in the Volunteers and took part in the famous “wet revue,” (1880?) as a result of which he caught pneumonia. Thereafter he was afflicted with a chest weakness which encouraged him to emigrate to Australia and to join relatives already settled there. He died at sea in the Indian Ocean.

My father, his eldest son, was aged about twelve when his father died and he was forced to leave school. At first he worked in a coal merchant’s office. Then he became apprenticed to a firm of architects, Clark & Bell. At the School of Art he became top student and won a scholarship which enabled him to study in France and Italy. In due course, he became a partner of the firm of Clark, Bell, & J. H. Craigie. When war was declared against Germany in 1914, Captain Craigie (although aged 44) joined up, as did his partner, George Bell Junior. They closed the office for the duration of the war and only resumed business in 1919. In public life he was a Justice of the Peace, Chairman of Cathcart Parish Council, and Member of Cathcart Ward Committee.

His most notable works of architecture were the re-construction of the Glasgow Law Courts, the re-construction of the Grosvenor Restaurant, and the building of Lewis’s Department Store, in Argyle Street, Glasgow. He was an Elder of the Church of Scotland and he was a keen member of Newlands Bowling Club. He was an upright man and a good father.

My brother James was his eldest son. He became a member of the Pharmaceutical Society and practiced all his life in Surrey, except for the years of Hitler’s War when he saw service in England, the Middle East, and Burma, in the Survey Section of an Artillery unit. He died in 1979, aged 70, leaving his widow, Irvine, and two sons, James and Robert.

The writer of this article was William Thom Craigie [b. Glasgow 19/08/1910 – d. Glasgow 29/09/1991]. He was the son of James Hoey Craigie [1870-1930, Glasgow], whose second wife was Roberta Jean Thom [1886-1920].

James Hoey Craigie’s father was James Craigie [1842-1882] of Kirkwall, Orkney, whose wife was Magdalene Hoey [1844-1929 of Glasgow].

The above James Craigie [b.1842] was the son of James Craigie [1799-1874 of Orkney], and his wife was Margaret Hutton Flett 1811-1884.

That James Craigie [b.1799] was the son of James Craigie and Jean Flett – and that James Craigie was the son of James Craigie [b. 1772, Kirkwall] and Marjory Reid.

…………………….

[I am indebted to Janet Craigie-McConnell of Victoria, Australia, for sending me a copy of this document for inclusion on the Rousay Remembered website.]